On June 19, 1865, about 200,000 enslaved people in Texas found out they had been freed by the Emancipation Proclamation two and a half years earlier, on Jan. 1, 1863. It has become a tradition for African Americans to celebrate freedom every year around this time, and according to the NAACP, “Juneteenth is a rich tradition that continues to promote education and self-improvement.”

For many, it is especially important to celebrate this day of freedom this year, given the nationwide protests over the recent deaths of Black Americans like George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, among others, at the hands of police. A push to make Juneteenth a federal holiday also is gaining momentum.

At Boise State, Black colleagues are coming together to formalize a Black Faculty and Staff Association that arose out of an expressed need for a more connected and comprehensive representation of Blacks at Boise State.

“‘I prayed for freedom for twenty years, but received no answer until I prayed with my legs,’ said Frederick Douglas. As we celebrate a holiday that commemorates the end of slavery in the United States, I can see that Boise State ‘has legs,’” said Michael Strickland, an adjunct instructor of communication who is helping organize the group. “There are more than 20 Black professionals at Boise State and we don’t really know each other. Being a Black person who is raising my kids here in Idaho, I want other Black people to see that and know that is actually a good thing, not a bad thing.”

Black professionals have been meeting, dining together and preparing for an active fall, Strickland said, with the following goals:

- To create a viable vehicle through which the campus’s Black community could come together

- To communicate ideas emanating from diverse areas and disciplines

- To act on specific issues to improve the conditions of Blacks on campus

- To eradicate inequities based upon racial and sexual discrimination

- To facilitate networking

“Having taught at universities in New Jersey, I took for granted that a university Black Faculty and Staff Association would have an annual meeting with the president, be able to file grievances or concerns as a group, be a place where Black professionals on campus can have a unique discussion,” Strickland said.

The group intends to expand to graduate students and other Black professionals connected to Boise State, and to offer monthly meetings and speakers open to all members of the campus community.

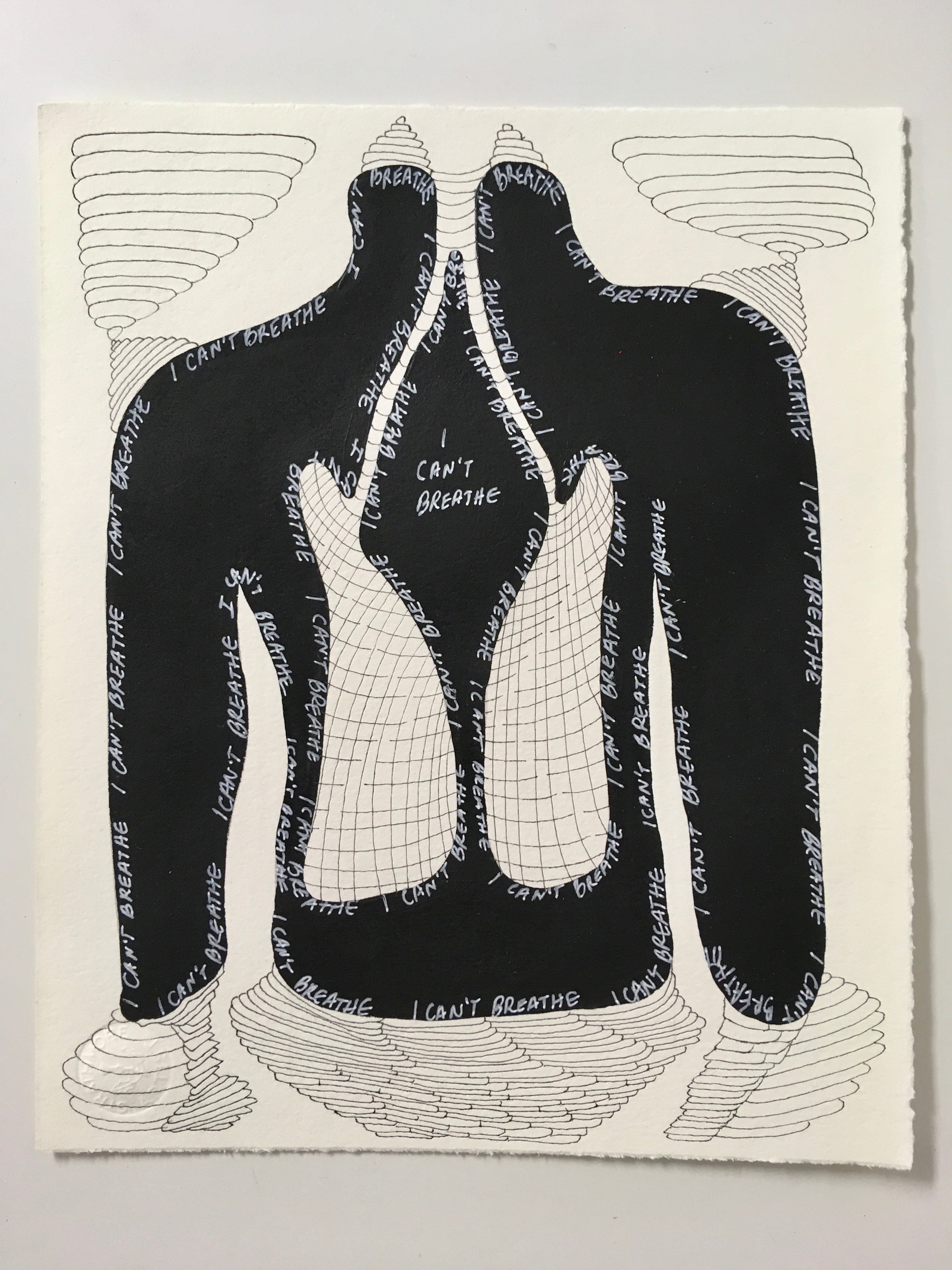

Photograph by the artist. Created in May 2020 in response to the murder of George Floyd (and others at the hands of police) and the disproportionate toll of suffering and death from Covid 19 in Black communities throughout the United States. As a light-skinned mixed race (Black/white) individual, I am working through my privilege to combat white supremacy and systemic racism and utilizing the power of visual art to prompt discussion and understanding.

Kirsten Furlong, a lecturer in the Department of Art, Design and Visual Studies and the director of the Blue Galleries in the Center for the Visual Arts, looks forward to being part of the community that the group will build. Moved by recent events, in May she created an acrylic and ink art piece titled “I Can’t Breathe.”

“This moment is incredible because so many artists are making work right now, creating an environment where we can simultaneously experience freshly made murals, paintings, posters, sculptures and more,” she said.

Covid 19 also means that art is being shared more widely online, on social media, in zines, digital media and prints, and on public streets and private homes and yards, she said.

That is important, because “the interpretation of the arts moves us in a particular physical, emotional and intellectual way and, at its best, prompts the viewer to think, react, and then act. The action is where the change can happen – making structural transformations and updating policies where racist ideas reside.”

Juneteenth has taken on a new meaning for her. Last year during the week of Juneteenth, she visited the National Memorial for Peace and Justice and the Legacy Museum in Montgomery, Alabama. She found them powerful in confronting the history of racial injustice through architecture, exhibits, art and design.

She hopes that reflection on Juneteenth also can be an observation of breaking free from the many historical and contemporary bondages that remain.

“This is essential to me, personally, as a Black/white biracial woman who is an artist and educator. I want to understand how these histories, along with white privilege and colorism, shapes me and my interactions with my students and colleagues,” she said.

“I have so much more work to do but appreciate the many difficult conversations that have recently begun.”