Riley T. O’Connor, Zachary Marcin, Dr. Emily Wakild

Introduction

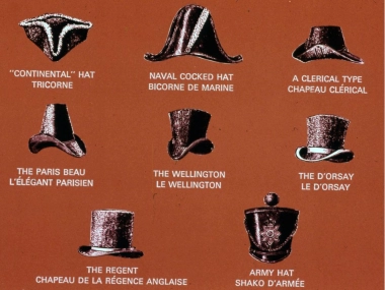

The American Fur Trade was an opportunity for the Indians to trade special items with the Europeans who travelled overseas. The Indians would give the Europeans beaver furs to make hats and other special clothing as a means of boosting their social status. In exchange, the Indians would receive firearms, cooking utensils, cloth, and other essential items.

Methods

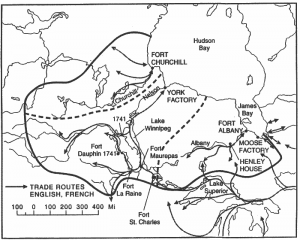

We had to search for historical trapper journals and books, including the Middle Ground by Richard White, in order to see how many beavers were harvested and where the furs ended up in. One set of data showed the paths that the various trappers took in order to follow the beavers. In turn, this would supply the fur trading companies with the necessary furs for production.

Analysis/Data

Through analyzing other scholarly articles and books, we have found that there are many social interactions between the Indians and Europeans. These would have an impact on the beaver population patterns and the Fur Trade. Exchanging fur for other essential supplies allowed for the Europeans to make delicate clothing out of beaver skins, thus boosting their social status. This was prominent in Southeastern Canada and Midwestern United States. A temporal range between the 17th and 18th century has been used to examine the cultural trends of the various social groups.

Conclusion

The fur trade not only impacted those that were found America, but also those who sent them from Europe, and depended on the trappers to supply Europeans with furs to make hats and other clothing.

Overall, the American fur trade created and changed different relationships over the course of history. These bonds ranged from communities as shown through the Indians and fur trappers. Another form of this was between fur companies and traders, as the traders provided the companies resources to make their products, whereas the companies created the fur demand that sustained the trappers.

Results

Overall, the American fur trade created different relationships that were both detrimental and beneficial for many people in both societies. Due to the trappers and Native’s relationship, many trappers were able to discover optimal hunting locations, while also receiving support from settlers. These relations also extended towards Natives and European Powers, as many tribes allied themselves with different powers, which caused them to be dragged into various conflicts due to these allegiances. Finally, Beaver Fur pelts were crafted into various different hats which often symbolized various levels of social status, or position within a particular group. Native Americans, Trappers and Fur Traders were heavily affected by the American Fur trade, and the connections of these groups changed many aspects of society. The Fur trade allowed many groups that under normal circumstances would not interact with each other come together and create a cooperative working relationship that lasted for many generations.

Survey/Data

Over the course of the project, our group had to focus on historical data instead of scientific data. As such, much of our information was supplied through trapper journals, company archives and historical articles. These data sources provided different details of social life within the American Fur Trade, and also showcased Native American and Trapper relations. This data was important in helping answer our research question, while also providing a better insight to life during the fur trade.

Additional Information

For questions or comments about this research, contact Riley O’Connor at rileyoconnor@u.boisestate.edu.