Dr. Iryna Babik, Quentin Cruz-Boyer

Abstract

The purpose of this study is to establish a positive relation between bilingualism and problem solving. Previous research indicated that bilingual children are more flexible than their monolingual peers in both processing of syntactic rules and spatial patterns [1]. Importantly, the same cognitive processes, responsible for the contextualization of a bilingual vocabulary, operate in a similar fashion with regard to all executive functioning. Essentially, bilingual children have greater reference from which to draw knowledge and find a solution to a particular problem.

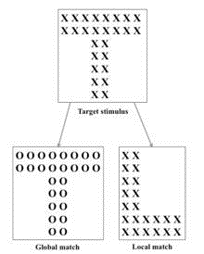

Bilingual children are more aware of the structural characteristics in language which can be linked to increased cognitive flexibility and improved pattern recognition via the visual cortex. In terms of Gestalt principles, which refer to compositional heuristics relating to visual perception, bilingualism facilitates a greater awareness of the parts which comprise the whole. This phenomena was not the result of cognitive inhibition, but rather a greater degree of executive control with regard to monitoring and shifting [2]. Moreover, bilinguals’ aptness for structural organization enables them to isolate dimensional matrices and formulate more creative solutions to otherwise commonplace problems given their enhanced ability to ‘differentiate’ [3].

Findings in Global-Local Processing

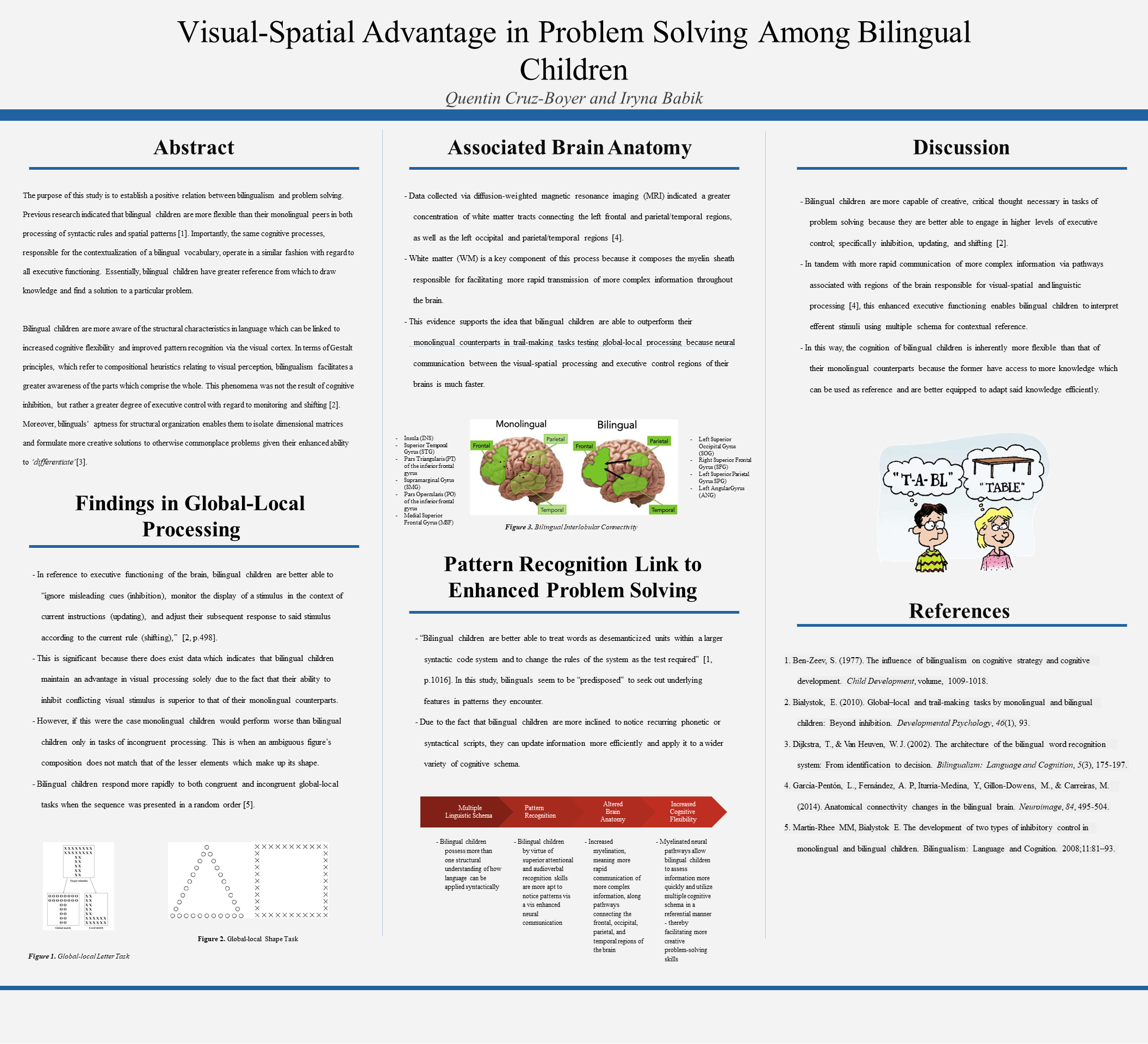

- In reference to executive functioning of the brain, bilingual children are better able to “ignore misleading cues (inhibition), monitor the display of a stimulus in the context of current instructions (updating), and adjust their subsequent response to said stimulus

according to the current rule (shifting),” [2, p.498]. - This is significant because there does exist data which indicates that bilingual children maintain an advantage in visual processing solely due to the fact that their ability to inhibit conflicting visual stimulus is superior to that of their monolingual counterparts.

- However, if this were the case monolingual children would perform worse than bilingual children only in tasks of incongruent processing. This is when an ambiguous figure’s composition does not match that of the lesser elements which make up its shape.

- Bilingual children respond more rapidly to both congruent and incongruent global-local tasks when the sequence was presented in a random order [5].

Associated Brain Anatomy

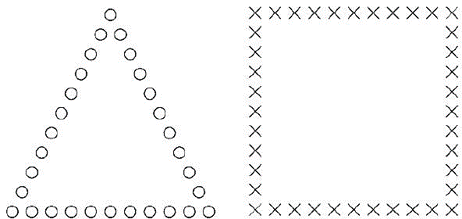

- Data collected via diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) indicated a greater concentration of white matter tracts connecting the left frontal and parietal/temporal regions, as well as the left occipital and parietal/temporal regions [4].

- White matter (WM) is a key component of this process because it composes the myelin sheath responsible for facilitating more rapid transmission of more complex information throughout the brain.

- This evidence supports the idea that bilingual children are able to outperform their monolingual counterparts in trail-making tasks testing global-local processing because neural communication between the visual-spatial processing and executive control regions of their brains is much faster.

Superior Temporal Gyrus (STG)

Pars Triangularis (PT) of the inferior frontal gyrus

Supramarginal Gyrus (SMG)

Pars Opercularis (PO) of the inferior frontal gyrus

Medial Superior Frontal Gyrus (MSF)

Bilingual: Left Superior Occipital Gyrus (SOG)

Right Superior Frontal Gyrus (SFG)

Left Superior Parietal Gyrus SPG)

Left Angular Gyrus (ANG)

Pattern Recognition Link to Enhanced Problem Solving

- “Bilingual children are better able to treat words as desemanticized units within a larger syntactic code system and to change the rules of the system as the test required” [1, p.1016]. In this study, bilinguals seem to be “predisposed” to seek out underlying

features in patterns they encounter. - Due to the fact that bilingual children are more inclined to notice recurring phonetic or syntactical scripts, they can update information more efficiently and apply it to a wider variety of cognitive schema.

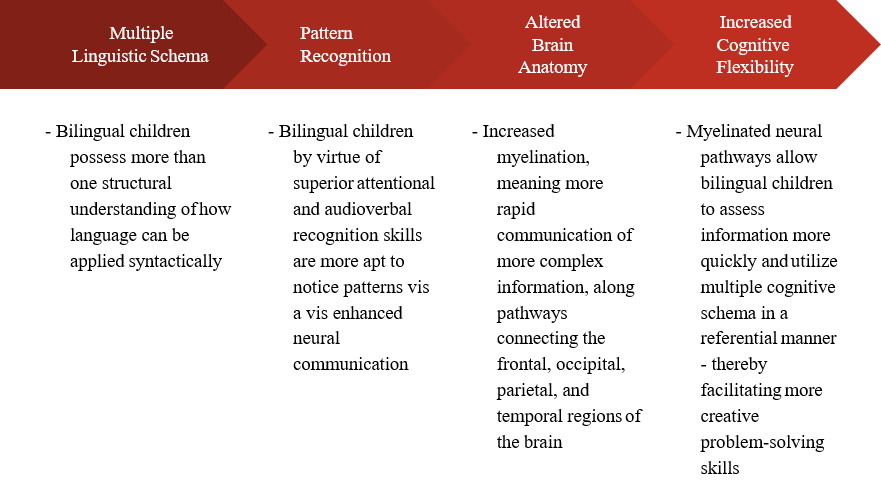

Multiple Linguistic Schema

Bilingual children possess more than one structural understanding of how language can be applied syntactically

Pattern Recognition

Bilingual children by virtue of superior attentional and audioverbal recognition skills are more apt to notice patterns vis a vis enhanced neural communication

Altered Brain Anatomy

Increased myelination, meaning more rapid communication of more complex information, along pathways connecting the frontal, occipital, parietal, and temporal regions of the brain

Increased Cognitive Flexibility

Myelinated neural pathways allow bilingual children to assess information more quickly and utilize multiple cognitive schema in a referential manner thereby facilitating more creative problem-solving skills

Discussion

- Bilingual children are more capable of creative, critical thought necessary in tasks of problem solving because they are better able to engage in higher levels of executive control; specifically inhibition, updating, and shifting [2].

- In tandem with more rapid communication of more complex information via pathways associated with regions of the brain responsible for visual-spatial and linguistic processing [4], this enhanced executive functioning enables bilingual children to interpret efferent stimuli using multiple schema for contextual reference.

- In this way, the cognition of bilingual children is inherently more flexible than that of their monolingual counterparts because the former have access to more knowledge which can be used as reference and are better equipped to adapt said knowledge efficiently.

References

- Ben-Zeev, S. (1977). The influence of bilingualism on cognitive strategy and cognitive development. Child Development, volume, 1009-1018.

- Bialystok, E. (2010). Global–local and trail-making tasks by monolingual and bilingual children: Beyond inhibition. Developmental Psychology, 46(1), 93.

- Dijkstra, T., & Van Heuven, W. J. (2002). The architecture of the bilingual word recognition system: From identification to decision. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 5(3), 175-197.

- García-Pentón, L., Fernández, A. P., Iturria-Medina, Y., Gillon-Dowens, M., & Carreiras, M. (2014). Anatomical connectivity changes in the bilingual brain. Neuroimage, 84, 495-504.

- Martin-Rhee MM, Bialystok E. The development of two types of inhibitory control in monolingual and bilingual children. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition. 2008;11:81–93.

Additional Information

For questions or comments about this research, contact Quentin Cruz-Boyer at quentincruzboyer@u.boisestate.edu.