LOCATION

The greenbelt extends along the Boise River and may be accessed from a number of locations. The most convenient access if you are visiting some of our urban environmental education areas is from BSU, the MK Nature Center and Kathryn Albertson Park.

ABOUT THE GREENBELT

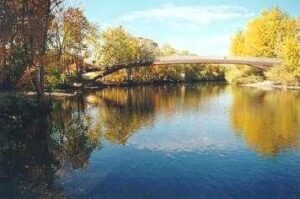

A wooded greenbelt extends 20 miles along the Boise River, from Eagle Island State Park to Lucky Peak Reservoir. The greenbelt accentuates an urban river that attracts fly fisherman angling for trout, whitefish, and bass. The wooded corridor connects six major urban parks, the wildlife sanctuary, nature center and native plant garden. Nest boxes in the corridor help attract native bird species to the area. The river serves as a winter migration route for the Bald Eagle; eagles can be observed perching and flying throughout the Boise area. Some fortunate visitors may also catch a glimpse of the Peregrine falcons that have been released from the nearby World Center for the Birds of Prey and hunt from the rooftops of a local bank and BSU’S Science/Nursing Building. The Discovery Center, Boise Zoo, Historical museum, and Art Museum are located between the MK Nature Center and Kathryn Albertson Park. Parks and museums on the north side of the river are connected to the BSU campus and the Great Basin Native Plant Garden on the south side of the river by a walking bridge. All of this is within one-half mile of the heart of the downtown area and Capitol Mall.

A BRIEF HISTORY

In the early 1960s Boise officials hired Harold E. Atkinson, a planning consultant from California, to prepare a new comprehensive land use plan and upgrade the city’s old and inadequate zoning ordinance. In his 1963 report to the city council Atkinson noted that there were several city parks and many other parcels of riverfront land in public ownership. He suggested the city acquire the Boise River property so as to create a continuous green belt of public lands stretching along the river throughout the entire length of the community. The Atkinson report stimulated the planning commission, the park board, and the park department to look at land ownership and acreage data and proceed with the planning of a linear park system. On January 24, 1966, the city council adopted a resolution making the “Greenbelt” an official city goal.

For the cover of the Boise Park Department’s 1967 Annual Report, an artist drew a cartoon of a little belt, complete with buckle, hatching from an egg. “Boise River Greenbelt Project is Born,” said the caption. The first acquisition had occurred in 1966, with the donation of a .43 acre parcel by the Taubman Corporation. Two more small donations followed in 1967. That same year the park board hired a local planning consultant, Arlo Nelson, to develop a workable plan. After a spirited discussion the city arrived at the guidelines it would adopt for the linear park in 1968. Billboards would be prohibited, as would tree cutting and overhead utility lines. The public would have “in perpetuity unrestricted access to the river and to the special and unique forms of recreation it provides.” After listing a variety of recreational uses and activities that would be compatible if adjacent to the Greenbelt, the statement added that residences and light office buildings might be “reasonably compatible” if they were separated from the Greenbelt by an adequate buffer zone. Two years later, a new item was added to the guidelines to include a function of the Greenbelt that had been overlooked in the original version, namely, that the greenbelt could use “delineated flood-plain properties on which permanent construction is necessarily restricted.” The city council amended the zoning ordinance in 1971 to provide for a minimum setback from the river and created the Greenbelt Committee to review any proposals that might come along.

The park department’s land acquisition program accelerated after 1970. When the city tried to purchase one 12-acre parcel for the Greenbelt the owners refused to sell except at prices greatly exceeding the appraisals. The city council condemned the land, whereupon property owners took the city to court. The council ended up winning, although paying more for the land than it had expected. The Council was now confident that the project now had a serious future. From then through 1977, the city acquired 17 riverfront tracts totaling 72 acres. Further development included wells for sprinkling, paths, grading, landscaping, decks, a skate and bike rental concession, and a footbridge connecting Boise State University with Julia Davis Park. The state transferred 52 acres east of town to Boise for the Municipal Golf Course, at that time the intended eastern terminus of the Greenbelt. The land was on the grounds of Idaho’s old penitentiary, but had been regarded as marginal for farming and most other uses because of its location on the floodplain.

An enthusiastic citizen constituency for the “continuous belt of green lands” included service clubs, environmental groups, the newspaper, local corporations, scout troops, and thousands of citizens who rafted, tubed, picnicked, fished, biked and cleaned up the river and its banks. These supporters, along with the city council, began to devote themselves to the idea that the Greenbelt path system for pedestrians and bicyclists should not have to cross streets and bridges. Engineers designed path extensions underneath the city bridges, none of which had been built anticipating such passages. Riders and walkers would not have to cope with dangerous motorized traffic.

The riverbed itself became the focus of civic action. In 1970 a 12-year old boy drowned after a metal pipe, part of an irrigation diversion structure, snagged his inner tube. An alarmed community, under the sponsorship of the local American Legion Post and the Idaho Department of Public Lands, undertook a massive and ambitious cleanup campaign. The Chamber of Commerce coordinated the efforts of the scores of corporate and government donors and a thousand individuals during the low-water season of 1971. The National Guard, the Seebees, Morrison-Knudsen, the state of Idaho, Boise State College and Boise High students, and fishing organizations did everything from removing and replacing diversion structures to picking up debris on the river bottom. The Sierra Club and the Jaycees allied with the 321st (Reserve) Engineer Battalion to haul huge concrete slabs, remnants of an old flood fight, off the banks near the Americana Bridge so the park department could install sprinklers, topsoil and a path. More was done the next year to remove remaining hazards, including the rebuilding of a diversion dam just below Ann Morrison Park.

The reluctance of some private property owners to defer to public interests on the river created conflict in 1974. The International Dunes Motel (now the Shiloh Inn) built its swimming pool within the Greenbelt setback and too close to the river, a violation of the by-then well-known zoning regulation. After the fact, the motel sought a variance to the setback, which the city board of adjustment denied. Upon appeal to the city council, it was denied again. International Dunes took the city to district court, arguing that the greenbelt setback was unconstitutional, among other issues. The judge dismissed the complaint and the motel had to comply with the setback.

By 1975 the greenbelt idea had burst out of the city limits into neighboring jurisdictions. The Ada County commissioners established the first public park in the county’s jurisdiction, reversing the century-old policy against having county parks. Forced to concede that traffic had become hazardous because of the random parking on the narrow road and bridge where floaters left their vehicles, they created Barber Park on the south side of Barber Bridge where people launched their tubes and rafts into the river.

Other governments joined in. The State of Idaho’s Department of Parks and Recreation observed the popularity of the river and the path system on its banks. The department considered how it might extend the system all the way east to its Discovery Park at the Lucky Peak Dam site, and later to a new state park on Eagle Island west of town near the town of Eagle. Garden City, a small enclave to Boise’s west, decided to adopt a general plan goal to continue the greenbelt through its jurisdiction.

Within 10 years the Boise City Greenbelt was a smash hit. The city had secured several miles of riverbank for the public’s perpetual “unrestricted access” to recreation, aesthetic enjoyment, and open space. The public in turn had spent thousands of hours of its labor and other donated resources on the project, an extraordinary civic investment. The river became the symbol of the high quality of life residents felt they enjoyed in Boise. The park board realized its early hopes that Boise would “turn to the river.” Finally, housing and office developers wanted to be there too. The Boise River was the place to be.

Once the river cleanup and public investment in the Greenbelt had transformed the river into the sparkling urban amenity, property owners who had been content with agricultural or industrial use of their riverfront acreage took another look. If so many people wanted to be along the river, then surely they would enjoy having offices and homes along the river. So, land developers entered the picture, and Boise spent the 1975-85 decade making, unmaking, and remaking its policies pertaining to the river. Because of the city council’s greenbelt setback ordinance, developers could not always get their buildings as close to the river as they would have liked, but had to compete with the public for access.

The entire decade of the 1970s was a period of substantial population and economic growth in Boise and Ada County. The old Atkinson Plan withered into irrelevancy when the city surpassed Atkinson’s 1985 population projection in 1976. Developers scrambled to keep up with the demand for new housing. The pace of growth was so rapid that the city was hard pressed to provide it with the normal city services. Coordinating and extending sewers, public safety systems, schools, and roads was part of the problem, but developers were also pushing to take advantage of the popular Greenbelt and build in the floodplain. In 1975, Mayor Dick Eardley appointed a citizens planning committee, which included developers and their engineers and other representatives to look at Boise’s comprehensive plan and what land-use philosophy would guide Boise’s flood-control ordinance. In 1976, the citizen’s planning committee presented its recommendations. In December of that year the Boise City council adopted an ordinance to “receive and accept” the guidelines presented by the committee as the basis for amending the city’s comprehensive plan. The document contained the following pair of policies on the flood plain:

The 100-year floodway of the Boise river should remain in a natural state as a greenbelt, wildlife habitat, or of an open space recreation nature with no structural development that will impede the flow of flood waters.

Limited development should be allowed within the 100-year floodway fringes; such development should not restrict or alter the natural flow of water within the floodway nor otherwise increase the size of the existing flood plain.

The focus of Boise’s river policy had undergone a subtle but significant change. The model and the regulations associated with it divided the flood plain into a “floodway” and “flood fringe.” The floodway included the river channel. The regulatory concept was to imagine the outer part of the flood plain filled or leveed against the 100-year flood up to the point where the flood level in the remaining channel and adjoining lands would not be raised any higher than one foot. The outer part would constitute the flood fringe and the rest the floodway. For the first time, development in the flood plain became part of flood plain policy. Residential and other private development could occur in the flood fringe if levees could be built to contain the river within the floodway.

Two months after the city council had “accepted” the principle of retaining the floodway for open space use, Emkay, the development subsidiary of the Morrison-Knudsen Company, filed an application for an office park, to be named Park Center. The land lay almost entirely in the flood plain, the majority in the floodway itself. To remove the land from the flood plain Emkay would have to build a levee along the length of its 125-acre property and extend the levee all the way to Logger’s Creek upstream from the site. In addition Emkay had to build an auxiliary channel across the Park Center development. The plan was approved by the city council.

Then came the River Run Subdivision proposal in 1978; the Forest River proposal to place a levee across from Ann Morrison Park between the 8th Street and Americana Bridges; the Plantation Subdivision; and Riverside Village.