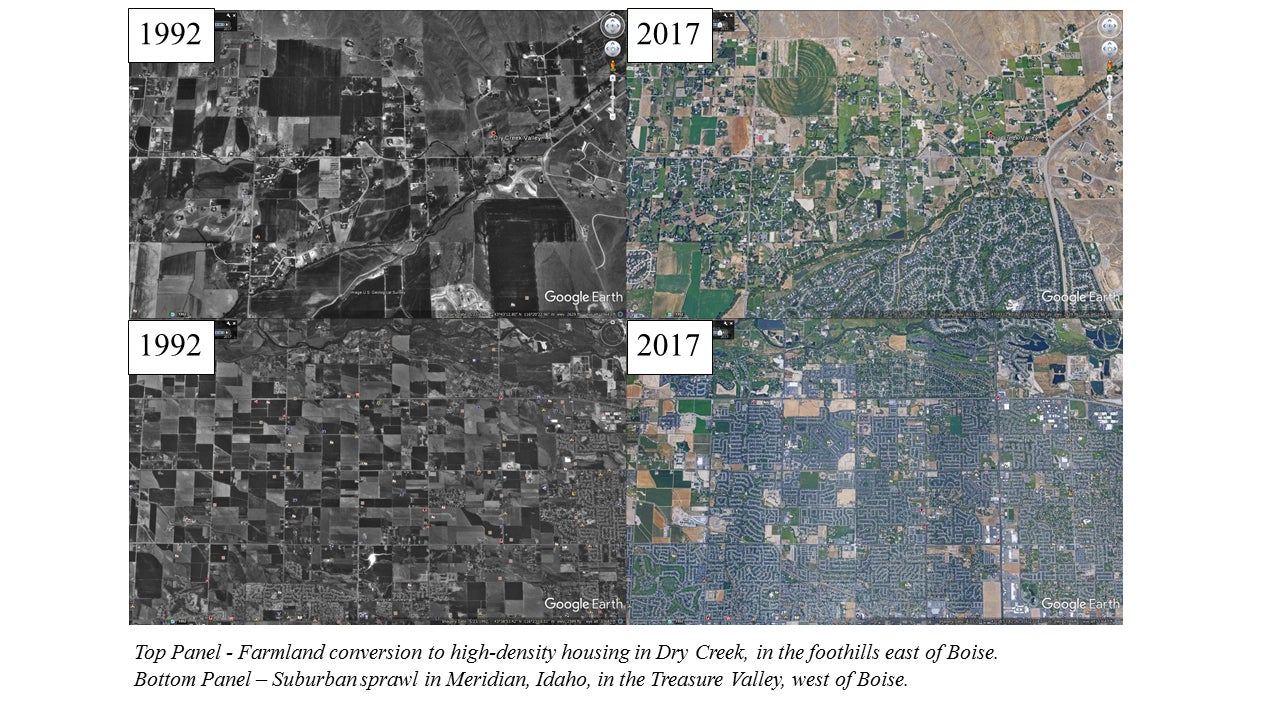

We’re losing farmland in the Treasure Valley – growth outpaces current efforts to preserve farmland

Article courtesy of Conservation the Idaho Way, a publication of the Idaho Soil & Water Conservation Commission. Originally published Feb. 2020; authored by Steve Stuebner.

The cities of Boise, Meridian and the Treasure Valley are in high-growth mode at a time when the economy is roaring, and Boise is frequently landing on the Forbes Top 10 best-places-to-live list, best place to retire, best place to enjoy outdoor recreation or even the best place to avoid government regulation.

Growth can be good for jobs and the economy, but it also can put additional stress on community resources – things like schools, roads, housing, etc. Another impact caused by growth in the Treasure Valley is we’re losing valuable farmland.

A Boise State University study recently concluded that if the current rate of growth continues, about half of the remaining farmland in the Treasure Valley, or about 200,000 acres of farm ground, will be lost forever by 2100. The valley currently has 387,320 acres of farmland. Looking back, from 1969 to 2012, Ada and Canyon counties lost about 30 percent of their farm acreage, while the state lost 18 percent over the same time period.

By 2100, the Community Planning Association estimates that the 1.25 million to 1.75 million people will live in the Treasure Valley.

“We have a long history of losing our farms to urban development, and it’s continuing today all across the eastern United States, and now we can see it in cities and towns in the great West,” said Mike McGrath, who helped develop a farmland preservation program for the Delaware Department of Agriculture.

“We have to do something,” said Brad McIntyre, of McIntyre Family Farms in Canyon County. “It’s inevitable that as our population grows, the housing has to go somewhere.”

But the value of buying farmland for new housing or shopping centers is much higher than, say, how it could be appraised for a conservation easement and preserving the land for farming. And right now, there really isn’t much of an alternative for farmers to consider other than to sell to developers when growth butts up against or surrounds their farms.

Farmland that’s in a location near existing housing might sell for $45,000 an acre in Ada County, and $15,000 to $35,000 an acre in Canyon County, according to Colliers International land broker John Starr. Vacant land within reach of existing city services such as sewer and water could sell for $85,000 to $100,000 per acre, Starr said.

While Canyon County farmers might buy up additional farm ground in the same county, Starr said he hasn’t seen that happen in Ada County in a long time.

Retired farmer Gary Drake told the Idaho Press that he sold his Kuna farm about 9 years ago. “A guy knocked on the door and offered me more money than I wanted, than I could ever make if I farmed it until I was 300 years old,” Drake said. “So I just said, you got it. Just one easy payment.”

This is the current challenge associated with preserving farmland in the Treasure Valley. Money talks, and it’s talking pretty much in only one direction.

“It’s kind of the Tragedy of the Commons – everyone wants to move to Boise, but where are we going to put all the newcomers?” notes Eric Grace, executive director of the Treasure Valley Land Trust.

Even if the conservation values of farmland can’t compete with offers from private developers today, Grace believes that value of farmland will go up over time. “In our view, preserving farmland is a very legitimate conservation value,” he said.

Josie Erskine, a small farmer and district manager for the Ada Soil and Water Conservation District, has been talking to a wide variety of groups in the Treasure Valley for about 10 years about preserving farmland. She sees multiple reasons for protecting farmland in the valley, including for the ability to grow food and livestock for local consumption, carbon sequestration and conservation.

“We have to save the farmland because it’s got soil on it, and we can grow things for the good of society,” she told the Idaho Environmental Forum in December. Small farms have a big value when you can grow food for neighbors, she said. “Even one acre of land in an urban zone is very valuable for food production,” she said.

But the issue has not risen to the point where it’s become top-of-mind and a priority for elected officials, county commissioners, legislators and farmers themselves. At least not yet.

Several officials are advocating for more comprehensive planning and leadership.

“I’m a proponent of managing growth,” said Starr, a Canyon County native who sells land to farmers and developers in the Treasure Valley for Colliers. “We need to really look at our values. We need a driving force for this discussion. We need leadership on the issue.”

Starr sees an analogy between the leadership that Owyhee County commissioners provided in launching the Owyhee Initiative process to preserve ranching in Owyhee County, with political leadership that could arise from the ranks of farm organizations, Ada or Canyon County elected officials to preserve farmland in the valley.

“Let’s not make the same mistakes others have made when it comes to growth,” he said.

“It’s not that much of a long-shot,” adds Erskine. “I think the support is there from the community.”

What’s at stake?

Canyon County currently has about 274,952 acres of cropland, an increase from 2012 because of new land that was brought into cultivation. There are about 2,290 farms in Canyon County. Recent information from USDA indicates the top crops by acreage in the county include:

- Alfalfa – 50,511 acres

- Pasture/hay – 47,235 acres

- Corn – 46,749 acres

- Pasture/grass – 33,000 acres

- Winter wheat – 29,470 acres

- Dry beans – 16,814 acres

- Herbs – 10,948 acres

- Sugar beets – 9,952 acres

- Onions – 8,326 acres

- Potatoes – 5,533 acres

In 2017, Canyon County farms sold $574 million worth of farm commodities. Big-selling categories include cattle and calves, grains, oilseeds, dry beans, dry peas, dairy, vegetables, potatoes, hay, and more.

In Ada County, there are about 1,300 farms on 144,000 acres of land. Erskine says Ada County has lost about 100,000 acres of farmland over the last 40 years. Many of the remaining farms in Ada County are smaller operations, less than 50 acres in size, according to USDA. Revenues from ag commodities in Ada County were $131 million.

Top crops in Ada County include hay and pasture, cattle and calves, corn for silage, wheat, winter wheat, and corn for grain.

Boise State public policy surveys show that Treasure Valley residents want to preserve not only farmland, but the culture of farming, officials said. In the 2016 Boise State Treasure Valley Policy Survey, 47 percent of the respondents said they were “very” or “extremely” concerned with the loss of farmland and 46.1 percent they were concerned about the loss of family farms.

Open space, and close proximity to nature and farming are important parts of life on the Treasure Valley, the researchers said.

“People aren’t just thinking about economics, they’re also thinking about the ways agriculture is part of the culture of this region, said Rebecca Som Castellano, an assistant professor of sociology at Boise State.

Roger Batt, a lobbyist for the Idaho Seed Association, points out that the Treasure Valley is one of five key areas for the global seed industry. The region produces 50 seed crops that are shipping to 120 countries around the world.

Batt saw the Boise State growth study as a wake-up call. “If we’re going to find an equitable solution, we’re going to have to do it in the next five to seven years. Otherwise, we’re going to be behind the curve,” he told the Idaho Press.

McIntyre knows a lot of farmers, and he said part of the issue is that some farmers are aging into the retirement zone, and they see selling their farm as their retirement. He said he would be opposed to preventing those farmers who want to sell from doing so.

“A lot of farmers are counting on that revenue for their retirement,” he said. “If a planning and zoning commission took a strict approach to protecting farmland, the value of their farmland could drop by one-third or more.”

That said, McIntyre hates seeing good farm ground with good soil get plowed under for a housing or commercial development. “There’s got to be some way to structure an ag land trust so that it doesn’t harm those who want to sell, and it doesn’t increase our taxes,” he said.

Erskine sees multiple ways for the Treasure Valley to preserve farmland, including using more strict planning and zoning regulations, more comprehensive planning, and creating some kind of farm trust through public financing.

“Our farm ground is going to become more and more precious over time,” she said.

Starr sees value in working toward higher density developments near Treasure Valley communities. Higher density means packing in more homes into a confined amount of space, and that will save farmland nearby, he says.

“The goal is to have as many homes as possible on an acre of land,” he says. “Lower density does nothing to protect farm ground; in fact, it puts more pressure on farm ground.”

As an example, take a square mile of land or 640 acres. If you have three units per acre, that would equate to 1,900 homes. If you have four units per acre, that equates to 2,560 homes.

“I would challenge the mayors in our valley and the county commissioners to commit to a level of density that’ll preserve farm ground,” he said.

In a white paper on preserving farmland, the Ada SWCD provided a list of potential options that other states have done, including:

- Tax breaks for farmers, forest land owners and ranchers who keep their land in agriculture. Voluntary program. A proposal similar to that approach was defeated in the Idaho Legislature several years ago.

- Tax-reduction program for ag lands where landowners make a 10-year commitment to not develop the land. About 16.5 million acres of land has been enrolled in the program in California at a cost of about $40 million. The state covers loss of tax revenue to local governments.

- Conservation easements purchased on ag land for conservation purposes while allowing the land to be farmed or ranched in perpetuity. This method is currently legal in Idaho, and it’s been used on ranch properties throughout the state to preserve conservation values on the ranch or in streams.

Erskine, Starr and others want to keep the conversation going on losing farmland in the Treasure Valley. The Idaho Ag Summit will feature a panel discussion on the topic on Feb. 18.

“There’s been a lot of talk about this issue over the last 5-6 years, but I don’t know what the answer is,” says Glen Edwards, a board member of Ada SWCD and a Kuna farmer.

The Boise State team of researchers looking into the issue have received another $200,000 grant to do more research on the topic. See link below.

Both Edwards and Erskine want to see more opportunities for younger people to get into farming as well to counter the age group that is looking at retirement now or in the coming years.

“There’s got to be a way to get our younger people into farming, but we all know they can’t start from scratch, it’s just too expensive,” Edwards says.

“People are hungry to farm,” adds Erskine. “We have more options in agriculture than people think.”

For more information:

- Ada SWCD has a web page on losing farmland and some solutions that have been tried in other states.

- Boise State University study on urban spawl and farmland preservation:

The Idaho State Soil and Water Conservation Commission promotes responsible stewardship by providing assistance and support for conservation projects on private lands. They provide incentive programs and technical assistance to promote and support Conservation the Idaho Way. With a staff of 19 employees located around the state, they also write voluntary Agricultural and Grazing Implementation Plans on Idaho’s 303(d) listed waterways, integrating a variety of best management practices to reduce pollutant loads and safeguard water quality.

While they began working over 81 years ago primarily to reduce soil erosion, our efforts now include soil, water, plants, air, and wildlife conservation activities. The Commission and their partners are the heartbeat of voluntary conservation in Idaho.

Steve Stuebner is a regular contributor to Conservation the Idaho Way.