Mel Fillmore is Hunkpapa, Lakota and citizen of The Standing Rock Sioux Tribe of North and South Dakota. They are a second year Ph.D. student who will continue to center American Indigenous narratives in public policy.

Lane Gillespie is an associate professor of criminal justice in Boise State University’s School of Public Service. Her research focuses on intimate partner abuse, victimization among underserved populations, and researcher-practitioner partnerships.

Findings from Idaho’s first Missing and Murdered Indigenous Persons (MMIP) report may be surprising to some, but come as less of a surprise to those who have been investigating cases, supporting families, and collaborating to raise awareness and responses. The average missing persons rate for Idaho Indigenous persons (18.99 per 100,000 persons) is almost double the rate for the state. Between 2016 and 2020 the annual number of Indigenous missing persons entries ranged between 72 and 93. Idaho’s Indigenous persons are disproportionately represented in deaths attributable to assault at about three times their proportion in the population.

These findings come from research aimed at determining the scope of MMIP as well as identifying challenges and opportunities relevant to this issue, as called for by the Idaho legislature. The MMIP movement has foundational grassroots within collective efforts of Idaho Tribes and non-profit organizations addressing issues of systemic violence. Broadly, this work coalesced to recognize systemic violence in Idaho through the lens of MMIP; parallel to national level efforts to address this issue. As media attention and public awareness on Indigenous victimization increases, engaging in continued discourse on MMIP and the impact on Idaho’s Indigenous populations is important.

Idaho Missing and Murdered Indigenous Persons Efforts & Research

There are five federally-recognized tribes with lands in the boundaries of Idaho: the Coeur d’Alene, Kootenai, Nez Perce, Shoshone-Bannock, and Shoshone-Paiute. In addition, there are Indigenous persons from these tribes and others that live across the state. Idaho is home to nationally recognized domestic violence and sexual assault service providers and advocates who are active in addressing gaps in multi-jurisdictional response to MMIP cases as well as broader social problems that intersect with MMIP (e.g., trafficking). Partners across the state (tribal, state, federal) have engaged and continue to engage in collaborations and research aimed at informing, relationship building, and responding to systemic violence, including MMIP.

In an attempt to unify state and federal agency strategies, the Idaho Coalition Against Sexual and Domestic Violence and partner entities hosted the first Idaho Summit on MMIP in December 2019. This Summit was a precursor to the development of House Concurrent Resolution 33 (HCR33) that passed both houses of the Idaho Legislature in March 2020. The Resolution was supported by testimony from tribal members, advocates, legislators, and the US Attorney’s Office for the District of Idaho. HCR33 emphasized engaging in research to understand the scope of MMIP in Idaho.

We collaborated on research responsive to this directive beginning in June 2020, resulting in a public report released September 2021. Our study combined quantitative – numerical – data on missing persons and homicides from seven sources with interview data gathered from 14 tribal and non-tribal stakeholders, responsive to HCR33’s goals. While research efforts were underway, the Coalition and its partners organized a conference in October 2020 inclusive of state agencies, federal agencies, researchers, advocates, and community members. A subsequent conference took place in October 2021, including the first public presentation of our Report findings. A MMIP subcommittee of the Idaho Criminal Justice Commission, convened September 2021, is tasked with identifying evidenced based practices and potential legislative recommendations for the state.

HCR33 committed Idaho to support ongoing efforts to identify the impact of MMIP, understand causes, and work collaboratively to identify solutions. Idaho is the ninth state to recognize missing and murdered Indigenous persons (MMIP) as a crisis and engage in statewide research to develop a better understanding of the problem.

Challenges in Missing Persons Cases

A significant challenge in addressing MMIP effectively is describing the extent of the problem. There are several sources of numerical data related to missing and murdered persons, including state clearinghouses, national clearinghouses, state policing data, and health data. In addition, tribes may track cases using their own methods. There is, however, no universal method of counting and tracking missing persons, which presents challenges to accurately determining the scope of the problem and to inter-agency collaboration on cases.

Yet counting missing persons is complicated. Missing persons cases are dynamic and several factors play into the inclusion of an individual into missing persons databases. Consider the following examples identified during our research:

- Adults can elect to go “missing.” In interviews, law enforcement stakeholders spoke to the challenge of balancing Fourth Amendment rights (protection against search and seizure) with the need to determine if a crime has occurred or if a missing adult is at heightened risk for negative outcomes for other reasons;

- Federal law mandates juveniles be entered into a national database, NCIC, within two hours of a report, but there is no standard for entering missing adults into criminal justice

databases; - Individual agency responses to missing persons vary. In Idaho, more than half of policing agencies have a missing persons policy, but policies are not universal;

- Missing persons data may represent individuals or entries. One individual may go missing on multiple separate occasions representing numerous entries. Understanding both are important;

- Accurate racial and ethnic identification in official records is a problem. Indigenous people may be misclassified as White or Hispanic. There is also a high proportion of Indigenous people who are multiracial and/or multiethnic, but not all missing persons data systems offer multiple fields for race and/or ethnicity. Additionally, a portion of missing persons entries are marked race “unknown;”

- Not all missing persons are reported to authorities, and not all reports are added to a missing persons database.

Challenges related to counting missing persons, and Indigenous missing persons in particular, are also factors in responding to missing persons and/or homicide cases. During our interviews, stakeholders indicated a range of factors impact identifying and investigating cases in the scope of MMIP, including the influence of policies and policy variation across agencies, resource constraints, level of training, level of investigation/report detail, responding to repeat missing juveniles, jurisdictional challenges and confusion, effective communication and access to information when multiple jurisdictions are involved.

Missing and Murdered Indigenous Persons in Idaho

Understanding these factors is important to contextualizing the process of counting missing persons. In order to establish a consistent method of counting missing persons, University of Nebraska Omaha researchers adapted an approach commonly used to count other “hidden populations” such as persons experiencing homelessness: point-in-time estimates. We followed this same approach, examining missing persons cases at three points-in-time during the first half of 2021.

Notable findings from missing persons and homicide data include:

- Idaho’s average missing persons rate is approximately 10.59 per 100,000 persons, while the average rate for Indigenous persons is 18.99 per 100,000 persons

- Indigenous persons are disproportionately represented among missing persons records at about two times their proportion of the population

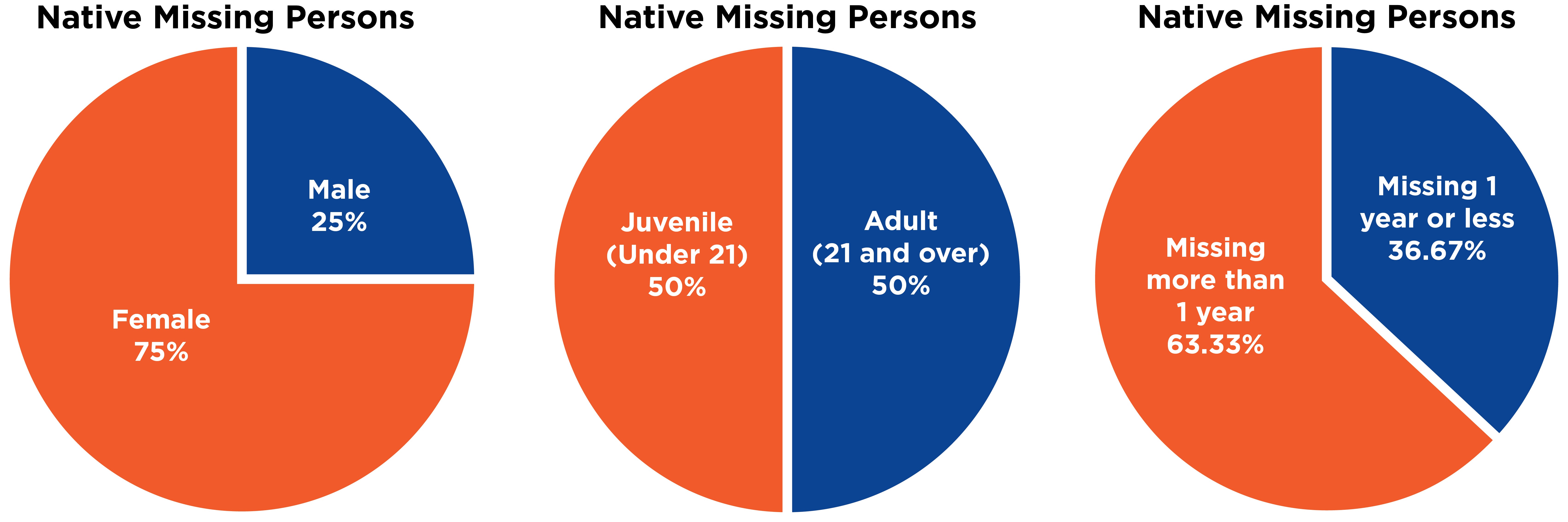

There are differences between Indigenous missing persons in the state and non-Indigenous missing persons in the state when looking at sex of missing persons, juvenile/adult status, and length of time missing

Age: Juvenile (under 21) 50%, Adult (21 and over) 50%;

Time Missing: Missing more than 1 year 63.33%, Missing 1 year or less 36.67%

Age: Juvenile (under 21) 61.5%, Adult (21 and over) 38.5%;

Time Missing: Missing more than 1 year 76.28%, Missing 1 year or less 23.72%

- On average in Idaho, there are 81.6 Indigenous missing persons entries in NCIC each year

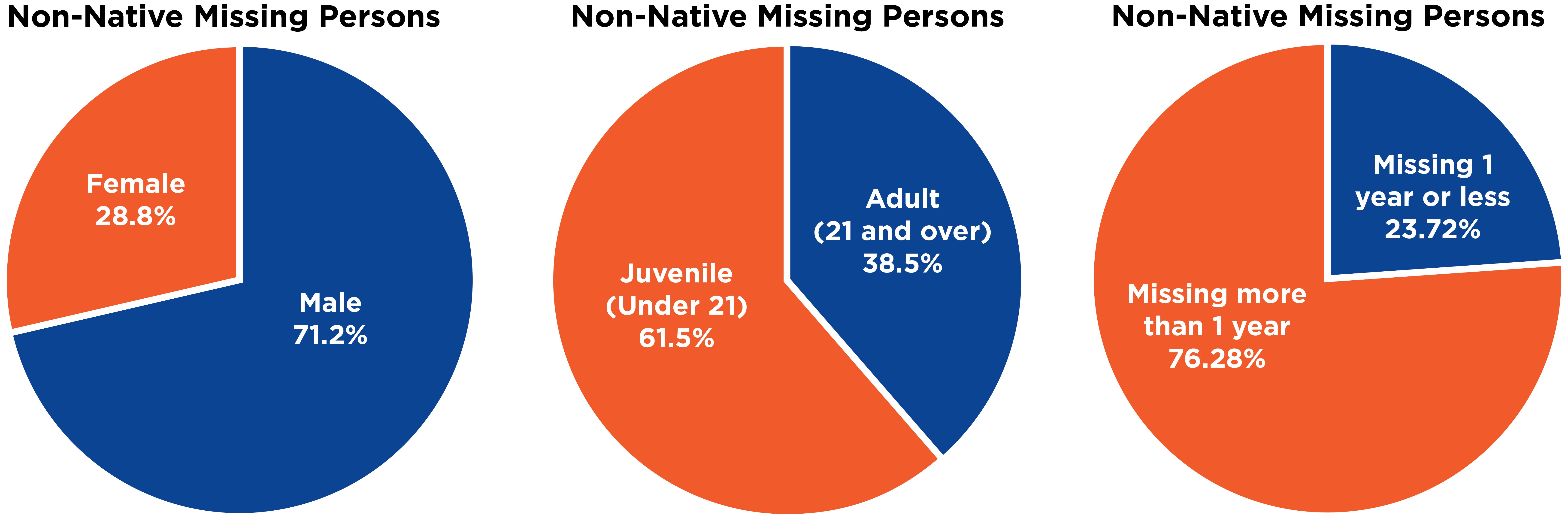

- Comparing NCIC data between Idaho and the U.S. indicates variations in entries by race, including percent of entries with ‘unknown’ race

National NCIC Entries, 2020: White: 59.27%, Black: 33.62%, Unknown: 3.36%, Asian: 1.98%, American Indian and Alaska Native: 1.76%

- Indigenous persons are disproportionately represented in deaths attributable to assault in Idaho. Data between 2010-2019 identified 20 assault death victims as Indigenous (3.05 times their proportion of the population)

- Homicide cases involving Indigenous persons occur in tribal jurisdictions and non-tribal jurisdictions

In addition to what numerical data tell us, there are several prominent themes that have emerged through MMIP research, two of which we spotlight here: criminal jurisdiction and victim services.

Complexities of Criminal Jurisdiction

Criminal jurisdiction on reservations and involving tribal members is complicated. Jurisdictional complications impact justice response to all forms of victimization, including homicide and non-voluntary missing persons cases. As one interviewee told us,

Let’s say, somebody goes missing off of the [reservation]. The tribal police, you know, would be heavily engaged in conducting that investigation. But once the investigation leaves the [reservation], then the question becomes what kind of collaborative cooperative working relationships does the tribal police department have with, you know, the [county sheriff’s office] or you know, wherever that may lead. And as soon as that leads to another state, it becomes further complicated […] And the tribal police has no ability to force them to investigate and the tribal police has no jurisdiction to go to their county or city and conduct their own investigation off of the reservation and so jurisdiction becomes important.”

(Stakeholder #4)

In some areas of the state inter-agency agreements are in place and community response plans are being discussed, while in other areas the relationships are not as strong or established between tribal agencies and relevant county or municipal agencies. Interagency agreements and/or cross-deputization for Peace Officer Standards and Training (POST)-certified Tribal officers would reduce some of the jurisdictional challenges. The National Sheriff’s Association recently published a guide on this topic, Cross-Deputization in Indian Country, and neighboring states have extended state peace officer status to tribal police officers.

Idaho MMIP stakeholders from tribal and non-tribal agencies alike expressed a desire to explore options for collaborative efforts moving forward, as well as avenues for creative responses.

Need for Victim Services

On the victim services side, there is a need for establishing and expanding services that support families of missing persons, formerly missing persons who may have experienced victimization, and families of homicide victims. Victim service providers and justice system stakeholders advocated for more support for families in missing persons cases, as well as more robust services for underlying issues that may put someone at risk for going missing or experiencing physical violence. Tribal service providers are at the front lines addressing acute needs of families who have lost or are searching for loved ones. Funding structures designated for domestic violence or sexual assault programming often do not address navigating communication with law enforcement for ongoing investigations, court proceedings, or long term missing persons cases.

Furthermore, service providers spoke to the need for space to engage in culturally specific healing practices. Here are excerpts from two interviews with stakeholders that make these points:

“We can, you know, create spaces for healing with one another also. And so I think that, that’s cornerstone to my work. Not only addressing this issue with my people but giving my people the language to navigate the trauma, the loss, the grief, the shock, the violence, and naming it in a way that keeps the community intact but is also very honest and very difficult.”

(Stakeholder #13)

“If I could wave a wand, I would like to have our office in a location where it wasn’t so visible to individuals. Where we could provide cultural events and activities.”

(Stakeholder #2)

Tribal service providers hold a depth of knowledge of tribal history, tribal-state-federal relationships, and trauma-informed care of victims’ families. Tribal service providers already have an understanding how settler-colonization has historically and systemically impacted Indigenous peoples access to justice systems and resources. Thus, service providers uphold and recognize traditional practices of respectful listening, offer privacy, and space when families share details specific to the proximity of violence missing loved ones may have experienced. Tribal service providers could be better supported with flexible resources as they connect families to traditional healers, ceremonies, or support groups to help families cope with the MMIP experience.

Momentum

Momentum on this issue has been building over the past three years: momentum towards raising awareness of MMIP, engaging in intergovernmental conversations, and state legislative action. Numerous recommendations have been made by those involved in MMIP efforts and based on research findings. Recommendations relate to improving data, training, and related resources; addressing jurisdictional challenges; supporting Indigenous victim services; enhancing capacity of existing resources; and identifying the most effective next steps. Indigenous communities have continued to make clear research and policy should reflect the mosaic of Indigenous tribes, cultures, and ways of being. Conducting localized research and initiating collaborative partnerships with all tribes and urban Indigenous populations is critical to identifying problems and developing solutions.