Why should I be a Mentor?

Mentoring support ensures that students will be well trained, successfully complete their degrees, and obtain promising job opportunities. The Graduate College is committed to cultivating a culture of mentoring in graduate education at Boise State University.

What is a Mentor?

Origins of Mentor

The term “mentor” is derived from a character in Homer’s epic tale, The Odyssey. Odysseus, the king of Ithaca left his wife, Penelope, and infant son, Telemachus, to fight with the Greek alliance in the Trojan War. He entrusted guardianship of his son and his royal household to an old friend, Mentor, anticipating a swift return. However, the Trojan War lasted ten years and Odysseus was prevented from returning home for an additional 10 years. Meanwhile, young nobles had long occupied Odysseus’ palace in hopes of taking control of Ithaca and denying Telemachus his birthright. Eventually the goddess, Athene, interceded to ensure Odysseus’ safe return. After their reunion, father and son repelled the usurpers and order was restored. Over time, the term, mentor, has come to mean an experienced and trusted adviser, especially one who advises those with less experience (Colley, 2000).

Colley, H. (2000). Exploring Myths of Mentor: A Rough Guide to the History of Mentoring from a Marxist feminist perspective. Retrieved from http://www.leeds.ac.uk/educol/documents/00001500

What is a Mentor?

Mentoring is a “personal and reciprocal relationship in which a more experienced faculty member acts as a guide, role model, teacher, and sponsor of a less experienced student. A mentor provides the mentee with knowledge, advice, counsel, challenge, and support in the mentee’s pursuit of becoming a full member of a particular profession” (Johnson, 2016, p. 23).

According to the Council of Graduate Schools (2008), mentors are:

- Advisors, who have career experience and share their knowledge.

- Supporters, who give emotional and moral encouragement.

- Tutors, who provide specific feedback on performance.

- Masters, who serve as employers to graduate student “apprentices.”

- Sponsors, who are sources of information and opportunities.

- Models of identity, who serve as academic role models.

Is there a difference between an advisor and mentor?

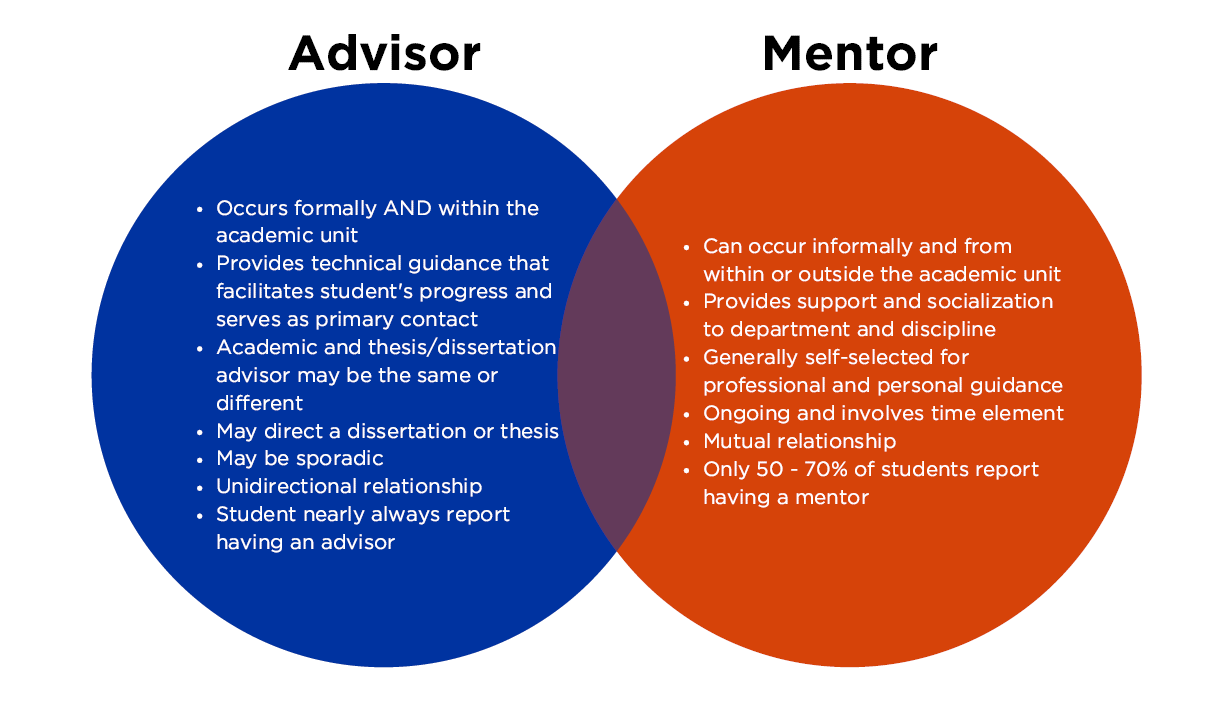

“Advisors and mentors are not synonymous. One can be an advisor without being a mentor and certainly one can be a mentor to someone without being that person’s advisor. It appears that far more students have advisors than mentors” (Johnson, 2016, p. 25).

Benefits of Mentoring

“Deliberate and thoughtful mentoring is one of the most important and enduring roles for the higher education faculty member” (Johnson, 2016, p. 3).

For Students

- more productive in terms of research activity, conference presentations, predoctoral publications, instructional development, and grant-writing

- higher completion rates and a shorter than average time to degree

- supports advancement in research activity, conference presentations, publication, pedagogical skill, and grant-writing

- less likely to feel ambushed by potential bumps in the road, having been alerted to them, and provided resources for dealing with stressful or difficult periods in their graduate careers

- the experiences and networks their mentors help them to accrue may improve their prospects of securing professional placement

- the knowledge that someone is committed to their progress, someone who can give them solid advice and be their advocate can lower stress and increase confidence

- constructive interaction with a mentor and participation in collective activities promotes engagement

For Faculty

- as students are more productive, faculty attract better students, extend their professional network of future colleagues, and amplify their own success

- a faculty member’s reputation rests in part on the work of his or her former students

- helping students make the professional and personal connections they need to succeed will greatly extend your own circle of colleagues

- good students will be attracted to you and you will be able to recruit outstanding students

- it is personally satisfying

Mentoring Competencies

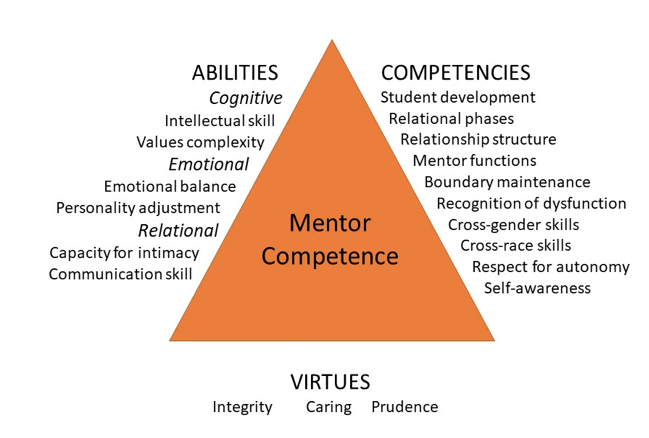

According to Johnson (2016), truly excellent mentoring in higher education requires the presence of foundational character virtues (integrity, caring, prudence), salient foundational abilities (cognitive, emotional, relational), and numerous skill-based competencies (e.g. providing support, respecting autonomy, etc). The triangular model below highlights the competencies.

Figure: Triangular Model of Mentor Competence (Johnson, 2016)

Developing the Mentoring Relationship

Developing the Mentoring Relationship

Johnson (2016) describes the phases of mentoring relationships, based on a model by Kram. Johnson emphasizes that while mentoring relationships with students will move through a “predictable developmental course, rarely will two mentorships follow an identical trajectory or arrive at major phases in the same manner” (pg. 97). The phases are:

- Initiation. The first several months of the mentoring relationship when both mentor and protégé are getting to know each other and settling into the relationship.

- Cultivation. This stage is the longest and steadiest phase of the mentoring relationship and may be one of the most enjoyable stages because the mentee is becoming more actively involved in the profession and may be contributing to scholarly projects.

- Separation. This phase begins slightly before or slightly after the protégé’s graduation and represents a dramatic shift in the relationship. The changes that take place during this phase can be difficult to manage but are important in setting the tone for the final stage of the mentoring relationship. The separation phase is often structural (mentee moves away) and psychological. Mindful mentors celebrate transitions while understanding that a range of emotional responses may occur.

- Redefinition. When the mentoring connection continues after separation, the relationship must be redefined to fit the reality of little contact and fewer needs. Not all mentees and mentors achieve comfort in a redefined relationship.

Acknowledgements

In creating this mentoring program, Boise State University has benefited enormously from other institutions with well-established mentoring programs. We wish to acknowledge the following resources that contributed to the building of this site:

University of Michigan, Rackham Graduate School