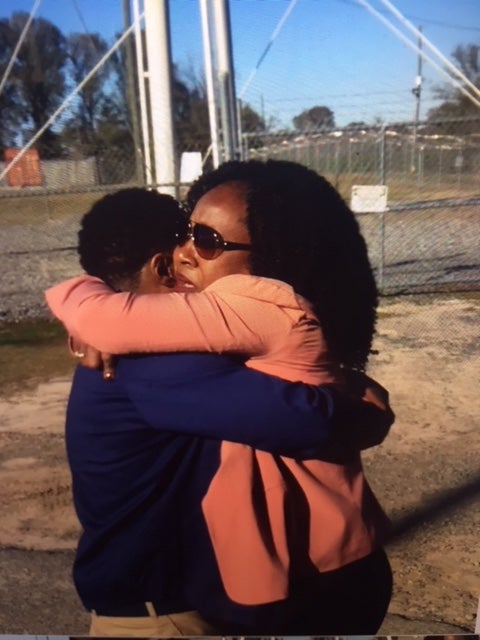

On Wednesday, authorities released Kerry Robinson, 44, from Coffee Correctional Facility in Nicholls, Georgia, into the arms of his family and friends. Robinson served nearly 18 years in prison for a rape he did not commit.

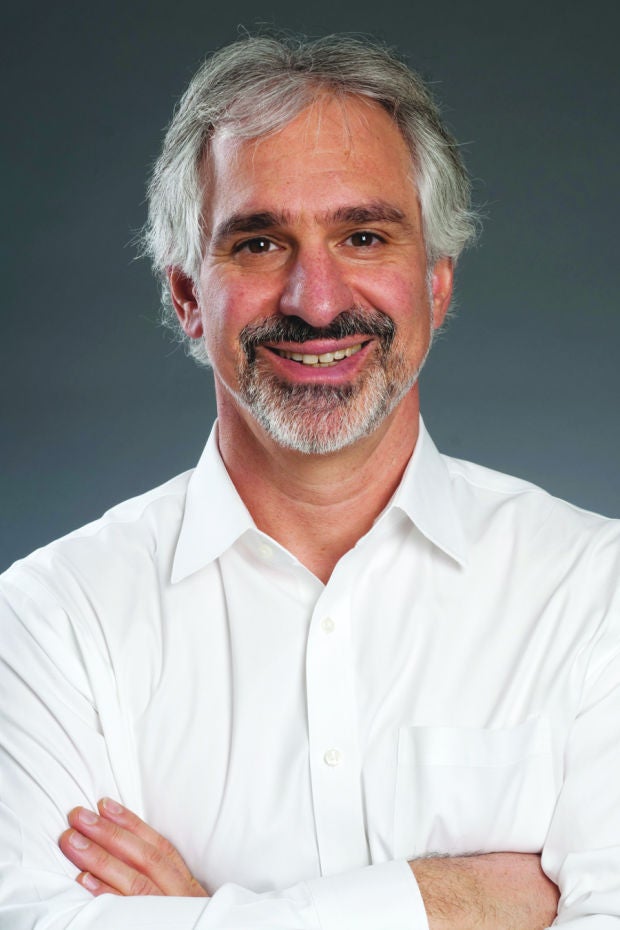

Boise State Professor Greg Hampikian, working with the Georgia Innocence Project and Rodney Zell, a post-conviction defense lawyer for Robinson, introduced new DNA technology that contradicted testimony during Robinson’s 2002 trial. Southern Judicial Circuit District Attorney Brad Shealy joined in Robinson’s motion to vacate his sentence.

“I’ve been waiting for this for 12 years,” said Hampikian, who is the executive director of the Idaho Innocence Project and director of the Forensic Justice Project at Boise State. “I am so relieved that Kerry is finally coming home, and while his mother did not live to see this day, I can almost hear her shouts of joy. My hope is that labs and lawyers will take notice and re-examine these complex DNA mixture cases that can mistakenly imprison the innocent.”

Hampikian called this case “perhaps the biggest work of my career in terms of its potential impact for others wrongfully convicted by the same methods.”

At Robinson’s rape trial, the jury heard testimony from a state crime lab analyst that suggested Robinson’s DNA likely was included in a DNA mixture from the sexual assault kit performed on the victim. The new analysis by Hampikian and experts at Cybergenetics (maker of TrueAllele software that analyzes DNA results with whom Hampikian has worked on cases in Idaho, Montana and New Mexico) proved the opposite: A random person’s DNA is far more likely to be included in the mixture of DNA obtained from the sexual assault kit than Robinson’s.

Hampikian proved that the expert testimony in Robinson’s case was deeply flawed and likely the result of subjective bias, not science. As part of a peer-reviewed study called “Subjectivity and Bias in Forensic Mixture Interpretation,” Hampikian and co-author Itiel Dror sent the DNA data from Robinson’s case to 17 DNA analysts for evaluation. Twelve analysts found that Robinson was not present in the DNA mixture; four could not draw a conclusion; and only one agreed with the Georgia Bureau of Investigation’s testimony. As part of his experiments, Hampikian also completed DNA testing on four staff members at a local Georgia news station and compared their DNA to that from the sexual assault kit. All four reporters’ DNA matched the DNA mixture from the sexual assault kit with as many or more markers as Robinson. Hampikian and Zell presented this information to a Georgia court at a hearing in 2012, but the court denied relief because it believed the new information simply resulted in a “battle of the experts.”

To help free Robinson, Hampikian secured grant funding to pursue DNA mixture cases, and spoke about the case across the U.S. and overseas, publishing editorials in the New York Times “The Dangers of DNA Testing, (2018)” and Forensic Science International, “Correcting DNA Errors,” (2019). His TedX talk on Robinson’s case “DNA Mix-ups,” is on the web, as well as features in Science (2015), and New Scientist (2011).

“In the dozens and dozens of complex cases we fight for every day, Kerry’s wrongful conviction stands out,” said Georgia Innocence Project Executive Director Clare Gilbert. “We more often see prosecutors stick to their own case, and ignore critical or new evidence which they didn’t see, or choose to see. District Attorney Shealy’s actions reflect the justice that we fight for, and we hope others follow this lead.”

Zell spoke of his years fighting to prove Robinson’s innocence.

“Now technology has confirmed what I’ve known for a long time,” said Zell. “I am so grateful that new technology is finally able to meet the incredibly high thresholds for righting wrongful convictions in Georgia. It’s been a long fight, but we are beyond thrilled to see Kerry coming home after all these years.”

In 2016, a presidential commission on forensic science citing Dror and Hampikian’s study found that human interpretation of DNA mixtures in crime laboratories was “problematic” because of subjective bias, and it concluded that “subjective analysis of complex DNA mixtures has not been established to be foundationally valid and is not a reliable method.”

In 2018, the Georgia Bureau of Investigation adopted a new DNA analytical tool called probabilistic genotyping that uses computer science and advanced mathematics to interpret DNA mixture results, effectively removing the subjectivity from mixture analysis. Through his grant funding, Hampikian worked with Cybergenetics to conduct probabilistic genotyping analysis. The analysis confirmed that the Georgia Bureau of Investigation trial testimony was wrong: a randomly chosen African-American is over 1,800 times more likely to explain the mixture of DNA in the sexual assault kit than Robinson.

Robinson’s case: the background

On Feb. 15, 1993, three teenagers broke into the home of a 42-year-old woman in Moultrie, Georgia, and raped her at gunpoint. The rape survivor never identified Robinson as the perpetrator. However, she identified two individuals from the pages of a local junior high school yearbook: a man named Tyrone White and White’s friend, who was later cleared by police after White falsely accused Robinson. Trial was delayed until 2002. After having nine years to investigate the brutal crime, the State presented only two pieces of evidence against Robinson: the accusation of White, a co-defendant with significant incentive to falsify his testimony and whose story contradicted the rape survivor’s own account, and the now-scientifically invalidated testimony of a DNA analyst. Still, the jury voted to convict.

Hampikian met Robinson once, during the failed hearing in 2013. He knew Robinson’s mother, Alvera Robinson, from a 2010 news story in which she spoke pointedly about White and the lies that helped put Robinson in prison. After her death not long after that interview took place, Hampikian kept in touch with Robinson’s sister Miranda Taylor who became her brother’s advocate. Hampikian never forgot Alvera Robinson’s voice, he said.

“She is present in every conversation with Miranda. It’s always the moms that push for their sons. The most heartbreaking part is when that bond is broken by death before their child is freed.”

Monsters & Critics recently featured the case in an article about Kim Kardashian and her legal advocacy work.