Boise State’s Grand Challenges are all about taking ambitious, complex issues and tackling them with interdisciplinary research and collaboration with the help of students, community stakeholders, industry, government, non-governmental organizations and fellow institutions of higher education.

When Jared Talley, an assistant professor of environmental philosophy and governance, heard about the opportunity to receive financial support from the Division of Research and Economic Development, he knew exactly what topic he wanted to focus on: carbon projects on lands in the American West.

A carbon project is when a company working to achieve carbon neutrality buys ‘carbon credits’ from land owners or managers. These credits represent one ton of carbon dioxide removed from the atmosphere. For example, an airline that is trying to achieve carbon neutrality could buy carbon credits from a farmer who practices regenerative agriculture and whose practices encourage ground carbon sequestration.

The surprising thing is that, despite the vast expanses of carbon-sequestering public rangelands available in the West, these lands are not being used for carbon projects. Talley and his Grand Challenge partners want to know ‘Why’?

Talley’s curiosity and engagement with community stakeholders hit the bullseye: he was awarded nearly $50,000 to further his research with a team of dedicated students. Regional stakeholders include Warm Springs Consulting, Idaho Department of Lands, Idaho State Department of Agriculture, Cecil D. Andrus Wildlife Management Area, Idaho Fish and Game, the United States Forest Service, Utah State University, rancher Bob Howard and Nevada Gold Mines, LLC.

“There’s 250 million acres of lands out here sequestering carbon, and there’s thousands of carbon projects across the world on all sorts of land types and jurisdictions. Why are there none in the West?” Talley said. “What needs to happen in order to be able to set up carbon sequestration on these sorts of rangelands and promote better management?”

These are big questions with significant economic and environmental impact for states like Idaho. Ranching is the predominant use of western lands, and Talley’s team wants to discover if different grazing management plans– such as grazing that focuses on soil health, fire management and wetland restoration – could impact how much carbon the soil can sequester. The more carbon that soil can sequester, the greater the economic opportunity for rural Idaho ranchers to contribute to their local communities through carbon projects, all while helping recover public land ecosystems.

To begin answering these questions, Talley’s group of six students traveled into the Cecil D Andrus Wildlife Management Area. There they collected soil samples and helped Talley figure out the logistics of credit development to see what infrastructure would be needed to scale up these projects in the state. The samples are analyzed for specific data points to see if regenerative ranching techniques positively impacted the soil’s ability to sequester carbon.

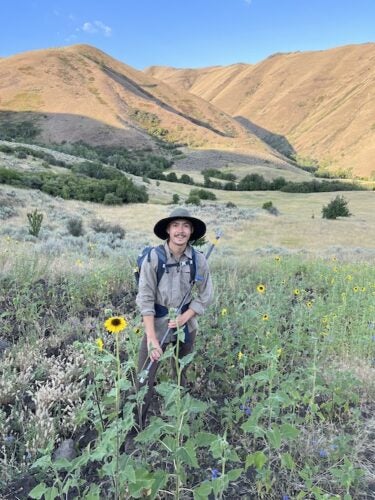

Phaedra Roby, a sophomore studying environmental studies and minoring in biology, was the team lead for one of the groups collecting samples. Camping in tents along the Idaho and Oregon border, the team carried buckets and augurs and collected five samples each day, in coordination with the US Forest Service and Idaho Fish and Game. The travel, coordination, camping and soil collecting, in addition to the realities of Idaho’s midsummer desert conditions “took physical and mental persistence”, Roby said.

Roby had never before been part of field work like this, but was eager to hone new skills outside of the classroom.

“I was given the job of driving my team’s vehicle to the nearest access point and back to home base at the end of each day. Due to the terrain and setting we were working in, we required both knowledge of the outdoors, of basic GIS and also carried along fire equipment to maintain fire code in the area. We logged vegetation, coordinates and soil texture tests on data sheets.”

While her Grand Challenge project role was her first foray into fieldwork, Roby says that post graduation, she intends to continue conducting impactful research for a better world.

“I hope to be doing something within wildlife conservation,” Roby said. “Whether that be working on better policy, or going in to restore injured habitats and wildlife, I know I want to be working towards a healthier place for everyone.”

Environmental studies alum Derek Freitag (’23) dove into the fieldwork alongside Roby and fellow students: environmental studies sophomore Cooper Simpson, geosciences alum Lacey Kerr (‘23), ecology, evolution and behavior doctoral student Yas Jafari, and environmental studies junior Haley Hester.

Like Roby, Freitag found the field work component to be a new challenge, and the autonomy of the student-led group was a novel experience. Ultimately, he felt that it helped him gain unexpected confidence in his field abilities, as well as a glimpse into conducting similar research in the professional world.

“The confidence that I was able to build by making calls in the field is invaluable to me and my professional development, and was such a fantastic take-away as I feel that this project helped to demonstrate what it is like in the real world, where you are not in a controlled environment where mistakes can be unmade by instructors,” said Freitag.

Since graduating in December of 2023, Freitag said that the Grand Challenge project had a profound impact on his education and how he can use research to help people.

“Rather than just learning about carbon cycles, I was able to see the material effects that this knowledge could provide for communities throughout our state. This project really spoke to me because it was a way to see how we could create real benefits for communities that need them most,” he said. “Ranching as a historical practice is an important culture within Idaho and the West at large, and this project aimed to both help slow environmental degradation, as well as potentially provide another means of revenue for a community that is very necessary for the functioning of our state.”

Please follow the Grand Challenges website for a follow-up article in which Talley’s Grand Challenge students take the next steps in this research and tackle the economic and policy quandaries of carbon credits in the West.

-By Brianne Phillips