Helina Alvarez grew up in Southern California, where the landscape shaped more than just her surroundings; it rooted her early love for habitat conservation and ecosystem preservation. From a young age, Alvarez understood that protecting the land was more than a scientific pursuit; it was a communal responsibility.

The first in her family to attend college, Alvarez earned a bachelor’s in wildlife management conservation from California State Polytechnic University, Humboldt. After working for the United States Fish and Wildlife Service for several years, Alvarez pursued a master’s degree from Colorado State University in conservation leadership, where she learned how understanding people – their histories, cultures and values – can be combined with ecology to support more effective conservation.

Now a doctoral student at Boise State University, Alvarez is pursuing a degree in ecology, evolution and behavior. She hopes to use her academic training and lived experience to uplift communities that are too often overlooked in environmental decision-making.

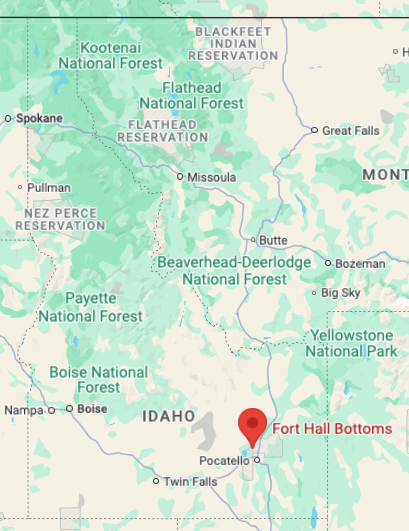

Alvarez’s current research brings her back to the intersection of heritage and science. She collaborates with the Shoshone-Bannock Tribe in southeastern Idaho, focusing on the Fort Hall Bottoms, a sacred wetland area affected by both climate change and colonialism.

Her work involves interviewing Tribal and non-Tribal members to understand how this vital water resource has changed over time and what those changes mean for the people who live there.

“There have been so many moments that have brought me to tears just having people trust me enough to share their stories,” she said.

Alvarez would regularly visit the Fort Hall Bottoms, building relationships and listening deeply. That process helped her see her research as a bridge between communities and knowledge systems.

“Just seeing how resilient Indigenous communities are when facing so many changes, for better or worse. I already knew that, but now I’ve seen it from a completely different tribe that I didn’t know about prior to living in Idaho,” Alvarez said.

This work, grounded in human connection and the changing conditions of the land, has been both intellectually and personally transformative. At its core, it’s all about learning from the land and the people who know it best.

Alvarez also brings her expertise to a statewide initiative known as I-CREWS (Idaho Community-engaged Resilience for Energy-Water Systems), a National Science Foundation Established Program to Stimulate Competitive Research – known as the EPSCoR initiative. This award investigates how shifts in the energy-water nexus affect vulnerable populations across Idaho. The team is particularly focused on who bears the burden of environmental change.

“We’re seeing less water in our systems,” Alvarez said. “Is that going to affect agriculture? Is that going to affect small farms? Big farms? Who is that going to affect? Who are those vulnerable groups?”

In both research efforts, Alvarez navigates the challenge and opportunities of integrating Western scientific methods with Indigenous knowledge systems. Sometimes these frameworks align; sometimes they clash. But Alvarez remains grounded in her commitment to learning, listening and contributing meaningfully.

Her hope is that this work, both the scientific research and the relationships built through community engagement, will inspire broader conversations about the collective responsibility in managing natural resources.

“[I hope people] realize how important it is, as we advance in technology and are consistently using our natural resources, to think about those who could be affected,” she said.

As she nears the completion of her doctorate, Alvarez is not just building a career, she’s helping reshape how science is done: with deeper respect for the land and for the communities whose lives are intertwined with it.

This publication was made possible by the NSF Idaho EPSCoR Program and by the National Science Foundation under award number OIA-2242769.