By Angela Fairbanks, content writer in the School of Nursing

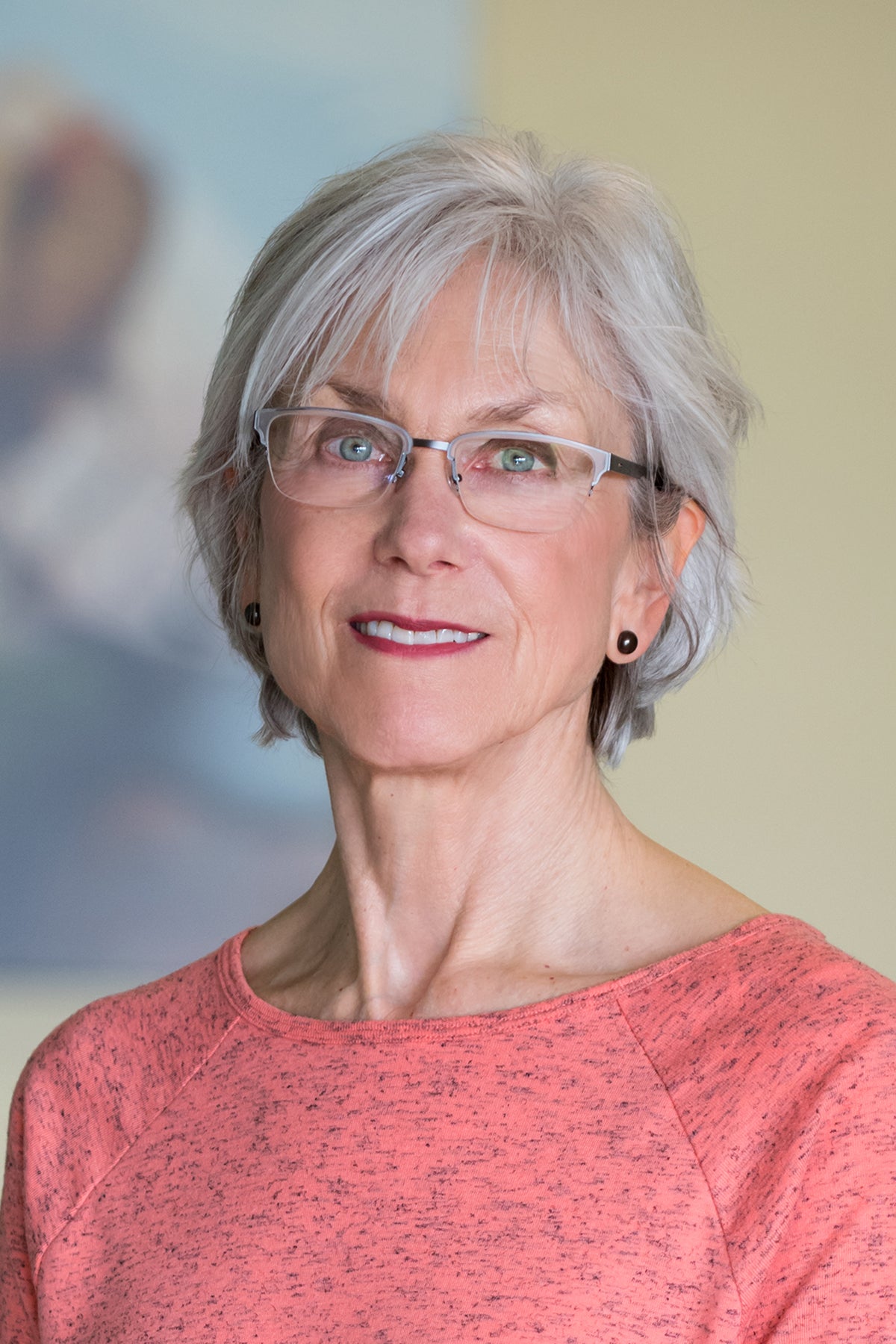

Nurses play a crucial role in lives around the world, and often work together with professionals in other disciplines to better care for medically vulnerable populations. Nurses join the ranks beside educators and law enforcement officers as mandatory reporters in instances of child abuse, maltreatment, and neglect. Karen Godard, faculty at Boise State University’s School of Nursing, has spent her career caring and advocating for at-risk children, both in her own practice and in that of her students.

“I’ve been working with children at risk for abuse and maltreatment for thirty years. Twenty of those years have been with children in foster care,” Godard said. “All children are medically vulnerable because they require adult care. When that care is interrupted in any way, that puts them at risk.”

Godard came to Boise State from Texas in 2007. From 2007 to 2019, Godard staffed and managed a healthcare clinic at the Nampa Family Justice Center in collaboration with Idaho Child and Family Services. There, she worked closely with children and families involved in the Idaho foster care and welfare systems. Her team conducted check-ups, provided medical advice, and served children coping with physical and psychological trauma. She also helped identify and report instances of child abuse.

That care can be interrupted any time a child is moved from one home to another, whether it’s a relative, foster, or group home. Over 460,000 children were in foster care in the United States in 2018, according to a 2020 report from the Children’s Bureau. Children in foster care are at higher risk for abuse, maltreatment, and neglect at the hands of adults or other children in the foster system.

“Foster care can be dangerous,” said Richard Wexler, executive director of the National Coalition for Child Protection Reform. Nationally, where data are available, “we see abuse in a quarter to a third of foster homes, and it’s worse in group-care institutions.”

In addition to her own work on the ground in public health and foster care clinics, Godard has taught over 800 nurses how to spot victims of child abuse and safely intervene. A past student, who has asked to remain anonymous, said “In the past, I have witnessed suspected abuse cases but I was hesitant to say anything. What if I offended the healthcare provider who examined the patient, or the patient’s caregiver? I no longer have that fear. If I feel that there is a reasonable suspicion, I am confident. I will not hesitate to intervene.”

Godard also brought several students to the Nampa Family Justice Center as part of the James Family Fellowship, providing service learning opportunities for students to understand child welfare, and receive hands-on experience in helping victims of violence. No students involved in the James family Fellowship could be reached for comment.

The number of youth in foster care in the United States has exceeded 400,000 every year since 2013. “People say it takes a village to raise a child,” said Max Veltman, associate professor of nursing, licensed pediatric nurse practitioner, and long-time colleague of Godard’s. “Every one of those children deserves the whole village, and everything we can give to them.”