Julie VanDusky-Allen received her PhD in Political Science in August 2011 from Binghamton University. She currently teaches courses in comparative politics, American politics, and research methods at Boise State University. With respect to research, she focuses mostly on how political parties adapt to institutional limits on their power. She also examines how US troop deployments influence foreign policy decision making in other countries. Additionally, Julie received a Fulbright research scholarship to gather data and teach in Mexico City during the 2008-2009 academic year.

Olga Shvetsova is Professor of Political Science and Economics at Binghamton University (SUNY). Professor Shvetsova’s research focuses on determinants of political strategy in the political process. Broadly stated, these include political institutions that define the “rules of the game” and societal characteristics that shape goals and opportunities of the participant players.

Andrei Zhirnov is Associate Lecturer in Quantitative Methods in Social Science at University of Exeter. He received his PhD in Political Science in 2019 from Binghamton University and studies political institutions and electoral systems.

As the total number of confirmed COVID-19 cases and COVID-19 related deaths in Brazil continues to drastically rise, the Brazilian government has become more scrutinized in the media for its perceived lackluster response to mitigate its spread.

The criticism of the federal government is not unfounded. In March, when many close members of Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro’s inner circle tested positive for the virus, he downplayed the threat. And although the Brazilian government was able to witness other governments’ responses to the pandemic throughout Latin America and the Northern Hemisphere, President Bolsonaro and the Brazilian national government refused to enact many of the now universally adopted measures that could potentially help stop the spread of the virus.

By the end of April, frustration among the Brazilian public mounted, and when reporters questioned President Bolsonaro about the rising number of COVID-19 cases in Brazil, he responded “So what? I’m sorry, but what do you want me to do?… I am not a miracle worker.”

Although it is reasonable to conclude that the Brazilian federal government has not adopted many important measures to stop the spread of COVID-19, the policy response at the subnational level in Brazil is a bit different. Much like the US, Brazil is a federal system. It is composed of 26 states and one federal district, all with policymaking powers. And much like the US, Brazilian states have taken the lead in enacting policies that to mitigate its spread.

So, the question is, how un-protected is the public from the pandemic? The answer is that it is much more protected than just looking at the national level policy outcomes alone would lead us to think.

To measure and compare the governments’ response to COVID-19 at the national and subnational levels, we use data for Brazil from the COVID-19 Protective Policy Index (PPI) project. The PPI measures public health government responses to COVID-19 at all levels of government throughout the world. The PPI measure considers the extent of COVID-19 policy responses in the following categories: state of emergencies, border closures, school closures, social gathering and social distancing limitations, home-bound policies, medical isolation policies, closure/restriction of businesses and services, and mandatory personal protection equipment. The coding for public health policies is based on government websites and reputable news sources reporting adoption of these policies.

Within the PPI dataset, we focus on the national and state government responses to COVID-19 in Brazil between February 1, 2020, and April 30, 2020. The index is measured each day for each state and for the federal government. It hypothetically ranges from 0 to 40, and is normalized here to fall in the range between 0 and 1, with lower values indicating a smaller response by the government and higher values indicating a larger response by the government.

Figure 1 presents an animated bar graph of the total PPI index for states throughout Brazil throughout the entire period in the sample. It also compares these values to the federal government’s response from Day 1, February 1, 2020, to Day 90, April 30, 2020. The data from the figure suggests that the Brazilian government acted first in responding to the COVID-19 crisis. But then many of the more populous states in Brazil, such as São Paulo, began to respond. And quickly more states began to adopt policies.

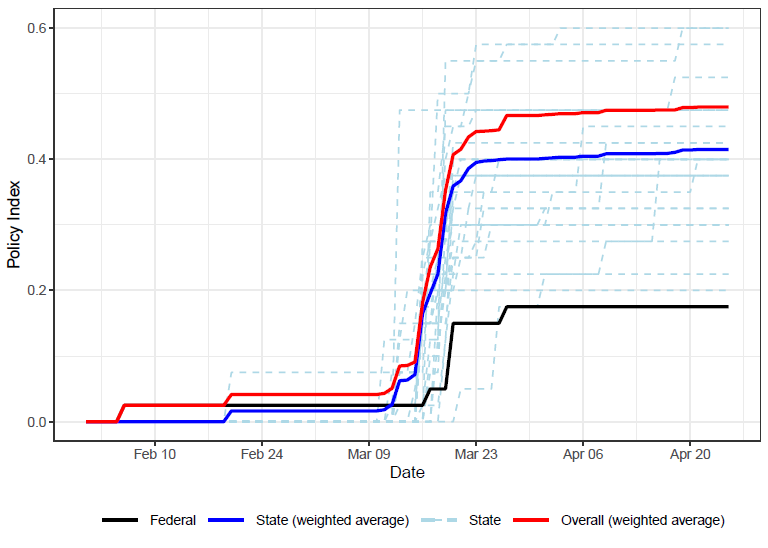

The data from Figure 2 paints a similar story. It presents the information from Figure 1 in line graph form but also includes an overall state average PPI weighted by population and an overall country PPI average, also weighted by population. The data suggest that the average policy response in Brazilian states surpassed the federal policy response on in mid-March. By the end of the 90-day period, all Brazilian states had a stronger policy response to COVID-19 than the Brazilian government did.

Additionally, the graph illustrates the importance of considering state level policy responses when determining the extent to which the government is protecting Brazilian citizens from the pandemic. By only examining the federal response, it would appear that Brazilian citizens are not well protected. But by examining the overall state average, it becomes apparent that Brazilian citizens are receiving a great deal of protection from their respective state governments.

Figure 3 presents an animated map of the total PPI index for states in Brazil from Day 38 to Day 90. It demonstrates that while most Brazilian states have adopted several policies to combat COVID-19, there is still variation among the states. In addition, we also observe that after considering the level of development in states, many states with an above average PPI, such as Bahia, Santa Cantarina, and Goiás, have a lower number of confirmed COVID-19 cases than the national average. In addition, many states with a below average PPI, such as, Amapá, Amazonas, and Roraima, have a much higher than average number of confirmed cases.

Hence, while the Brazilian federal government has not taken the lead on passing policies to mitigate the spread of COVID-19 in Brazil, many Brazilian states have. The existence of federal institutions in Brazil have aided the government’s response to the virus in spite of the federal government’s limited willingness to address the pandemic.

Of course, it is still important to note that these state policy responses are not without their challenges from the federal government. President Bolsonaro has openly challenged many state-level COVID-19 policy responses. He continues to expand the definition of essential businesses to combat state closures of businesses. He also openly criticizes state government policies on Twitter (which Twitter removed). And there are photographs of President Bolsonaro circulating in the press that show him openly ignoring the best practices in stopping spread the virus. Ultimately, as time progresses and more systematic research is conducted, we will know whether state government responses helped mitigated the spread of COVID-19 within their respective states despite the pushback from the federal government.

Note: This article is part of The Blue Review’s Coronavirus Conversations, a special series on the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic.