Todd Shallat, Ph.D., is professor emeritus of history and urban studies at Boise State University.

Namanny Asmussen is a junior majoring in applied science at Boise State University.

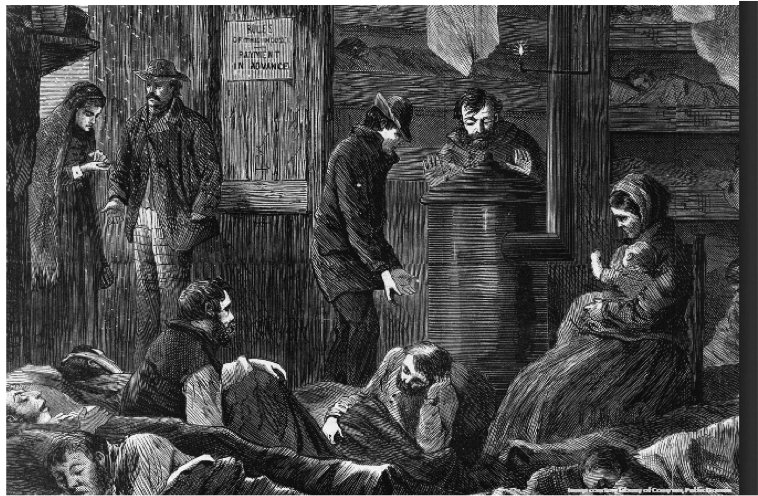

There was not enough water and soap in all of Boise to cleanse the stench of the county’s poor farm. So said health inspector J. K. White in his 1915 indictment of Ada County’s indigent care. The dilapidated farm north of Collister Station was “positively unfit for human habitation.” Horrid, squalid and infested with vermin, the farm was “disgraceful,” even “criminal.” White insisted that no one would voluntarily go there except as a last resort to cling to the last thread of life.

The condemnation cut deep into a city’s genteel sense of itself as progressively modern. High-minded Boise in 1915 had an electric trolley and, upriver, the world’s tallest dam. It had ballparks, opera houses, a symphony, a Carnegie library and a palatial Moorish resort with geothermal spas. Charitable institutions included the Old Soldiers Home and the Children’s Home orphanage on Warm Springs Avenue. But the city had no flophouse for transient shelter — nothing beyond the trackside camps for hobos and the drunk tank in the county jail. Its poorhouse was really a workhouse where the elderly and feeble-minded were given a cot and expected to farm.

Other Idahoans: Forgotten Stories of the Boise Valley

This essay is adapted from research in The Other Idahoans: Forgotten Stories of the Boise Valley, vol. 7, Investigate Boise Community Research Series (Boise State University School of Public Service, 2016).

Book launch: 5 p.m., June 10 at Rediscovered Books, 180 N. 8th St., Boise.

The farm grew wheat and hay on 160 acres off the Farmers Union Canal where Dry Creek drained the foothills. A rustic ward of indigent men had a single reeking outhouse. A detached building housed the farm’s superintendent and staff. The “inmates” were the diseased, the crippled, the detached and the dislocated. Racially mixed, women and men, they were mothers nursing infants, abused children, the blind, the crippled and the feeble-minded — never numbering more than 30 — misfortunates lost in the blur between rural and urban in a society without clear distinctions between the senile and the raving mad. Yet the stories remain mostly hidden. Historian Arthur Hart, writing for the Idaho Statesman, found only fragments in the public record and no clear understanding of the institution’s demise.

Still there remain fragments enough in the public record to question civic myths about Boise’s abundance. One is the myth of visionary capitalism; another, the fable that charitable associations made Boise a neighborly place. Historian Carol MacGregor has cited charity and capitalism as the social gospel that allowed early Boise to “prosper in isolation.” But not every citizen prospered. For the disabled and elderly poor, lost in the city’s shame and confusion, out-of-sight became out-of-mind.

ORIGINS OF ADA’S POOR FARM

Public welfare in Ada County dates from the era of the Boise gold rush. In 1864, an act of the territorial legislature had vested Idaho counties with the care of paupers. Ada County became one of four to establish a “poor house” on a county “poor farm.” But the problem was ill-defined and solutions always haphazard. Beggars were sometimes auctioned off to farmers or aided by churches or chased from the business district. Hospitals sent bills for paupers to the county courthouse. In 1882, the Statesman reported 15 years of public debt for indigent care.

Ada’s “farm” for the indigent and feeble-minded began in 1883 with the $5,000 purchase of 160 acres. The property had been subdivided from rangelands homestead by John Hailey, a sheep rancher and stagecoach entrepreneur. Today the closest landmark is the elementary school named for a Boise reformer who campaigned for public welfare, the schoolteacher Cynthia Mann.

Civic associations fed the hope in Ada County and elsewhere that public charity, being a “science,” was less expensive than hospital vouchers. Charity, it was assumed, would bridge the social classes, helping the poor become independent. “A little help will put our class of [poor] people in a way to take care of themselves,” reported the Idaho Statesman. Ada’s poor repaid the city by farming and clearing ditches — occasionally turning a profit. But it quickly became apparent that some inmates were too broken for outside labor. Ada commissioners struggled to make clear distinctions between the “able poor” who were healthy enough for labor and the “impotent poor” who were wholly incapable of working the farm. James Murphy of Boise, an “impotent pauper” without family in the Boise Valley, had been sent to the farm at age 71 after breaking an ankle. Another disabled inmate was a gray-headed pauper named Mr. Corder, age 79.

In a county that loathed taxation — so hostile to public spending that even the city’s drinking water was corporate — club women devised a genteel network of social welfare, raising money through charity balls. In September 1893, at Boise’s Natatorium, the Ladies Relief Society raised $333 for poor farm clothing and bedding. The society, said the Idaho Statesman, had established “a system of organized charity which is far more effective than any other method.”

For county taxpayers the biggest expense was the salary of the farm’s superintendent, usually a man who passed the job onto his wife. Eight superintendents lived at the poor farm from 1900 to 1912. Paid quarterly, their annual salaries ranged from $600 to $1,000 plus living quarters. Physicians asked about $800/year to supervise medical care.

Short-term contracts ensured short tenure for superintendents. In 1892, Superintendent Charles Stanton left amid allegations of violent inmate abuse. The county dropped criminal charges after an unnamed female withdrew the complaint. Schoolteacher M. E. Duncan filled the vacant position for $50/month.

MISFORTUNATE CIRCUMSTANCES

In October 1891, two years before the Warm Springs home for orphans, the Statesman reported the tragedy that “six unfortunate children had been thrown upon the county.” The six, called the Jewett children, had been discovered in squalor among transients from Iowa and Montana in a muddy shanty near Five Mile Road. Their mother had deserted her husband and run off with her brother-in-law.

Three others sent to the poor farm that same October were the Neal children of North End’s Arnold Addition. Elvira Neal, age 3, had been discovered with two young siblings, asleep on a soiled couch. Their mother was denounced as “depraved”; their father, a “half-crazed” prisoner in the county jail.

In the women’s ward, meanwhile, a young mother named Rose Storms cared for her infant daughter. From Minnesota, Storms had taken the train to Boise to wait for a suitor who never arrived. Storms and the infant joined 23 others at the Ada poor farm. One elderly man was said to have been a protester in Jacob Coxey’s “army,” a tattered march of the unemployed on the U.S. Capitol Building. Another was Cornelius Sproule of Nampa, who was suspected of being insane.

GRAND JURY INVESTIGATIONS

Scandal rocked Ada County when an audit uncovered that money had been spent on the poor farm for work than had never been done. At the center was Commissioner J. R. Lusk and $2,000 for road improvements. Lusk, a staunch Democrat, was a plumbing contractor who sold services to the county. His sheep ranch south of the city is now the Lusk District that borders Ann Morrison Park. Elected to the Ada County Commission in 1893, Lusk, it was alleged, had approved some questionable payments. The audit showed a fraudulent pattern of unearned per diems and mileage expenses. Lusk had also tapped poor farm funding for a fine bottle of cognac.

In 1897 the county approved a more vigilant system of audits. Reports showed that the poor farm, selling hay, could sometime cover expenses. In 1902 the Statesman reported that a preacher passing through Boise had praised the farm as a model poorhouse, one of the best in 42 states.

But the mood turned sour in 1912 with a series of damning indictments. A grand jury, convened in September, accused the poor farm of elder abuse. Bedridden inmates left unattended were too weak to reach the outhouse. A blind man in soiled sheets needed immediate hospital care. The physician was “derelict,” the superintendent “callous.” Jurors claimed that the farm’s animals got better treatment than paupers did in Ada County. Antiquated methods of care for sick and senile were “inhumane” and “everything least desired.”

Especially abhorrent was a medieval relic in the form of a metal cube to confine the insane. A “living room [for] crazy people,” the staff had called it. Standing nine feet, it resembled a steam boiler. Without wall padding inside the cube, patients could bang their heads.

At first the indictment went nowhere. District Judge Carl Davis opined that there was no evidence of malfeasance and it was doubtful that professionals employed by the county had broken the law. The farm’s doctor was forced to resign but noted in parting that “a poor farm was not an attractive place under any conditions.” It was too much to expect a poor farm to look like a home since, he explained, “the inmates are not from the neat and thrifty class.”

But scandal ignited two years later on Thanksgiving Day. Good Samaritans who had come to the farm with the traditional holiday turkey had found 10 ancient, gray-headed men, diseased and crippled. One was said to be 97. The state inspector returned to demand that the farm be condemned. “My recommendation,” said J. K. White, “would be to do away entirely with this old, dilapidated, germ-laden bug-infested building.” Without cleaning staff, the ward resembled a dungeon. “The system of having these old men take care of their own beds, wash their own clothes and take care of themselves [is] nothing short of criminal.” Commissioners were forced to concede that the poor farm concept, a throwback to the 1880s, was hopelessly antiquated. A modern progressive county needed a public hospital with a sanitary nursing home.

PERCEPTIONS OF PUBLIC WELFARE

Exchanging one sheep rancher’s plot for another, Ada County, in 1916, abandoned John Hailey’s pioneer farm above Collister Station for Eugene Looney’s 80 acres on Fairview where the trolley turned south at Curtis. The acreage had been purchased for tenfold the price of Hailey’s Collister farmstead, about $54,000. No longer known as a farm, the county institution became a respectable two-story building of sandstone with gardens on a manicured lawn. The Ada County Nursing Home, it came to be called.

Today it may seem repugnant that seniors with broken ankles would be left unattended, expected to farm to cover their care. Yet that was not how the program had started. Voluntary and temporary, poor farms had been conceived as humane but also spartan — a means of moral education through virtuous labor, a harsh deterrent for a class of paupers disposed to be indolent. By 1915, however, the nation had changed and so did the poor farm system. The rise of Progressive Era settlement house reformers — Jane Addams of Chicago was one, Boise’s Cynthia Mann another — shifted the urban focus to public health and sanitation. Crime, pollution, disease, and overcrowding in 20th-century cities demanded a coordinated and centralized municipal response.

Idaho, alas, was ill-equipped for municipal reorganization. Public works elsewhere funded by taxes — drinking water, irrigation, parks, trash collection, electricity and trolley transit — were privately owned in Boise. Public officials who served on county commissions were often businessmen with a personal stake in competitive enterprises. And so it was in Ada County. Suspicion of government, then as now, fed the distaste for public spending that crippled indigent care.

The Blue Review Homelessness Colloquy A TBR series on homelessness in Idaho.