A little noted side issue that emerged during the 1970s debate on the fate of the Sawtooths, the White Clouds, and Hells Canyon was the relentless march to the construction of the Teton Dam. Most environmentalists in Idaho opposed the project, but with the exception of activists around Idaho Falls, like Pete Henault and Russ Brown, few made it their priority.

Shortly after the dam was completed and the reservoir behind filled, the dam collapsed on June 5, 1976, with a loss of eleven lives and damages to property and crops climbing into hundreds of millions of dollars.

The day it failed Governor Andrus had set aside time to fly into the Idaho backcountry with his good friend, Rex Lanham, who owned and operated a fly-in lodge on Cabin Creek called the Flying W just off of Big Creek about ten miles above where Big Creek flows into the Middle Fork of the Salmon. Andrus planned on getting some restful fly fishing accomplished while restoring the batteries for a few days. Needless to say, he cancelled the trip upon hearing the news of the collapse and immediately flew over to the site of the collapse.

Note: This article is an excerpt from Chris Carlson’s new book, Hells Heroes: How an Unlikely Alliance Saved Idaho’s Hells Canyon, published by Caxton Press. Copies can be ordered from Caxton Press.

The most important, but little noted, consequence of the dam’s failure was the tendency of Andrus to more sharply scrutinize cost-benefit claims made by proponents of such projects. While he always believed some dams fulfill a legitimate and immediate need for hydropower or high head irrigation, he knew many projects had numbers that were “mickey-moused” to create better justifications.

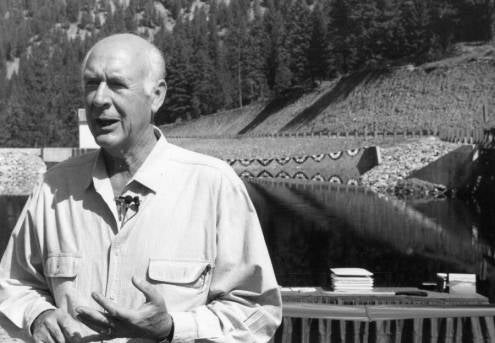

Because of the Teton Dam experience, Andrus was forever after able to exercise a more critical and credible review of the proposed projects and of those projects that had been built. In particular, he started increasing his criticism of the four lower Snake River dams, the last of which was completed in 1973 with Andrus present for the ribbon cutting. In speaking at the final dam dedication, the Lewiston Tribune reported his publicly questioning whether the Corps (U.S. Army Corps of Engineers) really understood the adverse impact the Lower Snake dams would have on downstream salmon and steelhead smolt migration.

Few folks recalled that earlier in 1973 Andrus, with a look of pure joy captured by Lewiston Tribune photographer Barry Kough, had dynamited a small regulating dam near Lewiston owned by what was then called Washington Water Power Co. Its removal restored the Clearwater to the exclusive list of those rare U.S. rivers without a single dam.

In later years, Andrus also bemoaned in his political biography, Politics Western Style, and in “historical look-backs,” his regrets at supporting the four lower Snake River dams and the Dworshak Dam on the North Fork of the Clearwater. He recognized well after the fact how much excellent elk habitat and quality cutthroat streams had been sacrificed on the altar of the Bonneville Power Administration and the Army Corps of Engineers.

He also recognized that had he opposed Dworshak Dam and the four Lower Snake dams he might well have not been elected as the State Senator from Clearwater County for much of the 60s decade. Given his lasting impact on issues he championed while in public office, especially his key role in guiding the precedent-setting Alaska lands legislation through Congress into law in 1980, I, for one would accept the trade-off as nonetheless a net-gainer for the environment.

As the evidence mounted of the devastating impacts of the four Lower Snake projects on Idaho’s prized and valuable salmon and steelhead runs, it became clear to Andrus that a “bad trade off” had been made. Upon his return to the governorship in 1987 he started formulating the elements of a fish flush plan on the Snake that would emulate nature’s spring flow critical to quickly carrying the salmon and steelhead smolt to the sea.

At the end of the day it was Senators Jim McClure and Frank Church who delivered the Hells Canyon National Recreation Area bill to President Gerald Ford for signing.

Even the Lewiston Morning Tribune, which seldom had anything good to write about McClure, gave him a “cheer” and applauded his key role in securing passage of the NRA law.

In a laudatory editorial on December 21, 1975, the Tribune wrote:

“Twenty years in the making, the Hells Canyon Recreation Area will become a reality upon the signature of President Ford. Approved by Congress Friday, the bill essentially preserves the free-flowing status of the Middle Snake River south of Lewiston. . . .Credits for establishing a recreation area for Hells Canyon must go, of course, to early day environmentalists whose foresight delayed further power company designs on the already concrete-choked Snake River. Back pats must also be given to members of Congress from the northwest, like Representative Al Ullman, Senator Robert Packwood, and Senator Frank Church, who were behind the legislation from the start.

“But the highest tribute should be reserved for Idaho Senator James McClure, whose pro-recreation area stand placed him at odds with many of his fellow conservatives, and those segments of industry from whom he receives much of his campaign support. McClure led the Senate passage and helped to overcome House opposition, championed mainly by his fellow Republican from Idaho, Rep. Steve Symms. McClure steadfastly held out, however uncomfortable, against pressure from political allies to soften his stance.

“McClure placed the welfare of future generations over political expediency. For that, he deserves recognition. A gold Star for Jim McClure.”

Others might term it an Idaho example of profiles in courage.

Chris Carlson is a journalist and former communications consultant who worked for many years for Governor and Interior Secretary Cecil D. Andrus. He lives at Medimont, Idaho.

Chris Carlson is a journalist and former communications consultant who worked for many years for Governor and Interior Secretary Cecil D. Andrus. He lives at Medimont, Idaho.