Julie VanDusky-Allen received her PhD in Political Science in August 2011 from Binghamton University. She currently teaches courses in comparative politics, American politics, and research methods. With respect to research, she focuses mostly on how political parties adapt to institutional limits on their power. She also examines how US troop deployments influence foreign policy decision making in other countries. Additionally, Julie received a Fulbright research scholarship to gather data and teach in Mexico City during the 2008-2009 academic year.

Beyond the establishment of free, fair, and competitive elections, another key indicator of a healthy democracy is when losing candidates accept the legitimacy of election results and concede to the winners. Unfortunately, the electoral process is messy and sometimes losers do not recognize the results of elections. This is especially true in newer democracies, where there could be a plethora of reasons as to why losers will not recognize elections results. Candidates that may have been in power for a long time may not want to step down. Candidates could have also engaged in voter intimidation and vote buying, which could lead to voters questioning whether the election outcome truly reflected voters’ preferences. In a similar vein, it is also possible that foreign powers influenced the election results in some way, and if so, voters may question whether the results would have been different without foreign interference. Furthermore, there could be also be irregularities with the vote count. If one or more of these conditions are met, the losing candidates and their supporters may use these circumstances as an excuse to not recognize the legitimacy of the elections and call for new elections.

THE FALL AND RISE OF THE PARTIDO REVOLUCIONARIO INSTITUCIONAL (PRI)

Mexico is one of the many democracies in the world today that has struggled with establishing free, fair, and competitive elections where losers concede. Although Mexico has had a long history of presidential elections, they have only had truly competitive presidential elections since 2000. From 1929 to 2000, a single political party, the Partido Revolucionario Institucional, or the PRI, was able to ensure that only the PRI candidate would win. They did this through (1) creating a centralized party organization that consolidated power in the president’s office, (2) controlling access to political positions and state resources throughout Mexico, (3) providing private benefits to both party members and voters in exchange for their support, and (4) creating laws that made it harder for opposition parties to compete.

In the 1980s and 1990s, however, PRI members and voters began defecting to other parties, and PRI leaders began to lose control over elections in Mexico. Due to these losses, the PRI made concessions to make it easier for PRI members to choose presidential candidates, for opposition parties to run, and to allow the Federal Election Institute (IFE) to monitor elections. As a result of all of these changes, in the 2000 presidential election, the PAN candidate, Vicente Fox, won with 42.52% of the vote. The PRI candidate, Francisco Labastida, only received 36.11% of the vote.

THE LEGITIMACY OF THE 2000, 2006, AND 2012 MEXICAN ELECTIONS

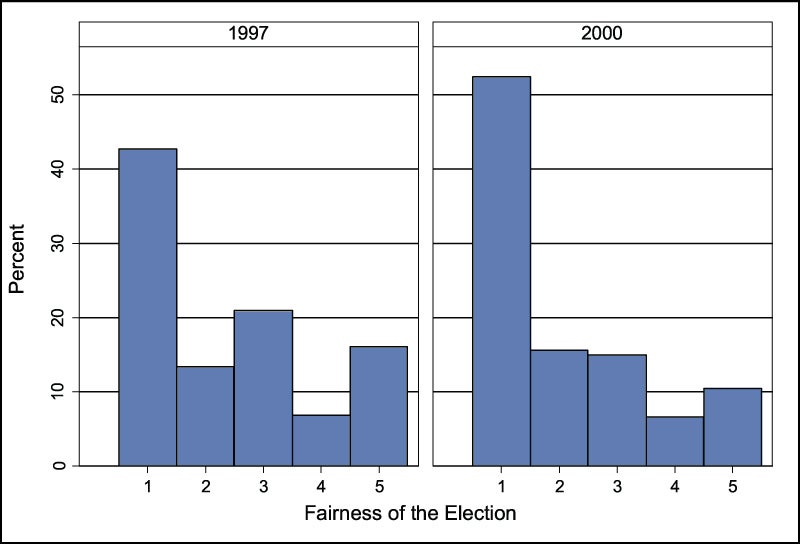

To assess the impact that the 2000 Presidential election had on the perception of the legitimacy of the election results in Mexico, I used survey data from the Comparative Studies of Electoral Systems dataset from 1997 and 2000 that focused on how voters viewed the “fairness” of the previous elections. Respondents could answer 1 to 5, with 1 indicating that the respondent thought the election was conducted fairly and a 5 indicating that the respondent thought the election was conducted unfairly. As you can see from Figure 1 below, about 43% of respondents said the election was fair after the 1997 Congressional election and about 52% of respondents said the election was fair after the 2000 Presidential election.

This data suggests that Vicente Fox’s victory as the first non-PRI candidate to win a Presidential election in Mexico in seventy years made it more likely for voters to believe that elections in Mexico were becoming freer, fairer, and more competitive. As a testament to the legitimacy of these elections, despite his party’s loss, the outgoing PRI President celebrated the outcome of the election in his televised address to the nation after the election, where he proclaimed that “The next President of the republic will be Mr. Vicente Fox Quesada. … Today we have proved that our democracy is mature.”

Figure 1: Perceptions of Fairness of Mexican Elections

While the results of the 2000 Presidential election suggested that elections in Mexico were moving towards being freer, fairer, and more competitive, the results of the closely competitive 2006 election once again threatened the legitimacy of the electoral process in Mexico. Felipe Calderón, the PAN candidate, received 35.89% of the vote, while Andrés Manuel López Obrador (also known as AMLO) of the PRD received 35.31% of the vote, and Roberto Madrazo, the PRI candidate, received 22.26% of the vote. Since the vote share difference between Calderón and López Obrador was so tight, the IFE ordered a review of the results. Ultimately the IFE declared Calderón the winner, but López Obrador contested the results and demanded another recount. The results of this recount still put Calderón as the winner. López Obrador and the PRD, however, refused to recognize the results of the election and instead held several peaceful demonstrations to contest the results. López Obrador even went as far as holding an “unofficial inauguration” ceremony for himself, in which 100,000 people attended, and where he claimed to set up a parallel government.

The results of the 2012 presidential election did not bode much better in helping to continue to legitimize Mexican elections. Despite its long history of non-democratic governance in Mexico, and despite suffering two election loses in 2000 and 2006, the PRI was able to make a comeback in this election. PRI candidate Enrique Peña Nieto won the election with 38.2% of the vote. The second closest candidate was once again López Obrador of the PRD, who received 31.6% of the vote. While the results of this election made it clearer that more voters voted for Peña Nieto than López Obrador, there was widespread claims that the means by which the PRI won the election were illegitimate. In particular, there were claims that the PRI offered voters gift cards to the grocery store Soriana in exchange for their votes and that they employed children to serve as lookouts at polling stations to ensure voters marked their ballots appropriately. As a result of these claims, there were once again protests across Mexico challenging the results of the election.

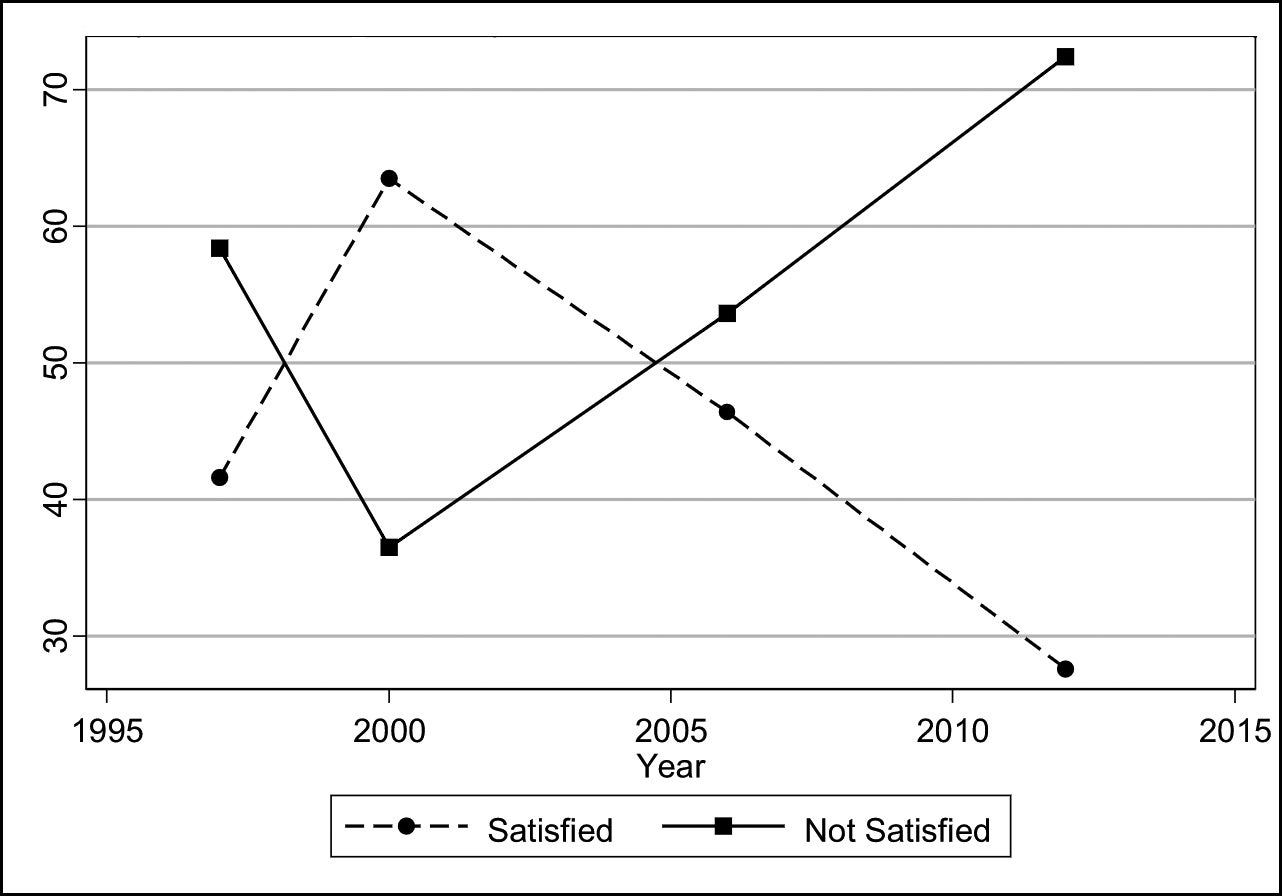

The experiences of the 2006 and 2012 elections in Mexico likely undermined many Mexicans’ views of the quality and value democratic outcomes in Mexico. To illustrate this point, I use survey data from the Comparative Studies of Electoral Systems dataset on citizens’ satisfaction with democracy. In the survey, researchers asked respondents how satisfied they were with the democratic process. Respondents could answer “Very Satisfied,” “Fairly Satisfied,” “Not Very Satisfied,” and “Not At All Satisfied.” I combined the two satisfied categories together and the two not satisfied categories together. Graph 1 displays the results below.

Graph 1: Percentage of Respondents Satisfied and Not Satisfied with Democracy

As illustrated by the data in the graph, despite the fact that elections have become a bit more competitive in Mexico since 2000, Mexicans in general have not become more satisfied with democratic outcomes. Although the data clearly demonstrates that the results of the 2000 Presidential election likely led voters to be more satisfied with democracy, that boost with satisfaction has significantly diminished over time. While issues with poor governance, particularly with respect to the Mexican government’s inability to win the war against drug cartels throughout Mexico, should certainly make Mexicans less satisfied with democratic outcomes, the controversies surrounding the 2006 and 2012 Presidential elections should have also reduced voters’ satisfaction with democracy. Since most voters voted against the winner in both elections, and since the legitimacy of both elections were called into question, it follows that voters likely began to slowly distrust the democratic process and election outcomes over time. Furthermore, what is most striking about the data from Graph 1 is that today Mexicans are less satisfied with democracy than they were in 1997. In other words, despite the fact that elections are freer, fairer, and more competitive than they were in the 1990s, Mexican voters today are less satisfied with democratic outcomes than when they lived under a semi-democracy.

PROSPECTS FOR THE LEGITIMACY OF THE 2018 PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION

Mexico holds its next round of elections on July 1, 2018. In terms of the candidates, instead of running as a single party, the PRI candidate, José Antonio Meade Kuribreña, is running in a three-party electoral coalition, Todos por México, which consists of the PRI, PVEM, and Nueva Alianza parties. The PAN candidate, Ricardo Anaya Cortés, is also running in a three-party electoral coalition, Por México al Frente, which consists of the PAN, PRD, and MC parties. López Obrador is also running once again as a candidate, but not as a PRD candidate this time. He is running as a candidate for the Juntos Haremos Historia coalition, which consists of the MORENA, PT, and PES parties. Based on the most recent polling, López Obrador is ahead. Of course, the election is several months away so it is unclear whether these polls can accurately predict the winner at this point.

The outlook for the legitimacy of the 2018 Presidential election outcome is already looking dim. As in previous elections, there are already accusations of vote buying. And since there are three major candidates running for office, it is not unlikely that the vote share could be close enough for the losers to contest the election results if there are any credibly accusations of election fraud. These domestic conditions alone could undermine the legitimacy of the election results in July and the losers’ willingness to accept the outcome of the election.

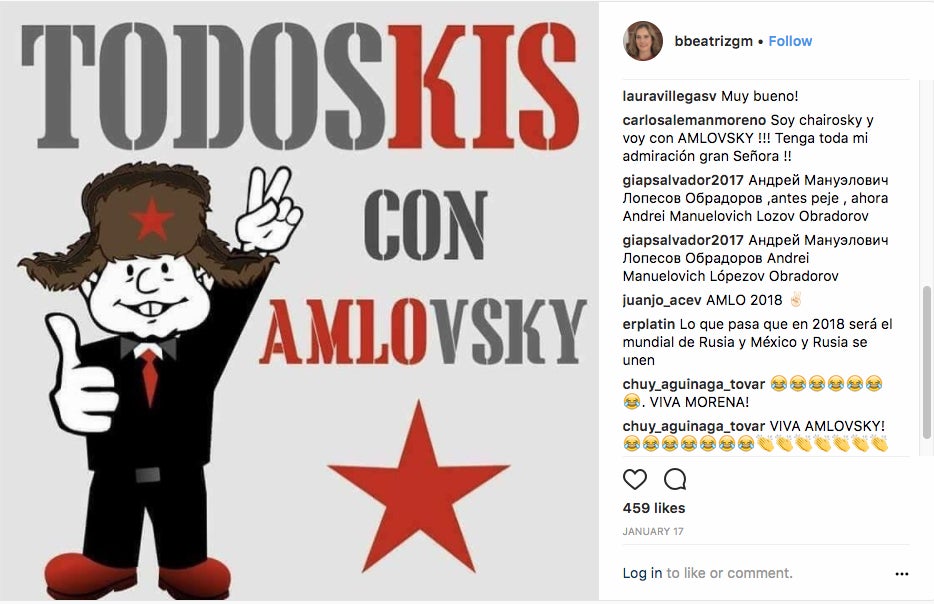

Unfortunately, international factors in this year’s Mexican Presidential election can further delegitimize the election results. In the last two months, the United States has warned Mexico that Russia is trying to influence the election results. In particular, Senator Marco Rubio (R-Florida) and Senator Bob Menendez (D-New Jersey), as well as Secretary of State Rex Tillerson and U.S. National Security Advisor HR McMaster have noted that Russia is trying to polarize the Mexican electorate through the use of propaganda on social media in order to undermine the democratic process and the legitimacy of election results. If this is the case, it is already working. The PRI has already used this information to claim that Russia is trying to help López Obrador win the election.

If López Obrador does win the election, claims of Russian interference could undermine the election results and his presidency. Of course, if he does not win, he could claim that Russia (or the United States) interfered with the election to prevent from him from winning and he could once again contest the results. In either circumstance, it is likely that this year’s election results will be more controversial than the 2006 and 2012 elections results. If Russian election interference is capable of undermining confidence in democratic institutions in a country like the United States that has a history of free, fair, and competitive elections, one could only imagine the impact Russian election interference could have on confidence in democratic institutions in a young democracy with a history of tumultuous election experiences.