Tim Atwell is an English major at Boise State University. He is the fall intern for The Blue Review. He enjoys running on the greenbelt and camping.

This is the lead essay in a TBR series on Boise homelessness. We sent Tim Atwell’s article to about a dozen members of the community — homeless activists and advocates, public officials and homeless people — and requested their reactions in writing. We will publish the TBR Homeless Colloquy throughout the coming week. — Eds.

According to my phone, it was 6 degrees Fahrenheit. The sun had set early, leaving the sidewalk slick with ice. I moved slowly to avoid slipping. A large man pushing a shopping cart on the far side of the road stopped to watch as I struggled to keep my balance. The closest visible light was the red glow of a cigarette, glaring at me from the front seat of an unmarked white van. I tucked my ski jacket close around me and walked faster, but I had to stop and leap into the street to avoid a dark-cloaked figure sprinting past me.

By the time I reached the shelter, I was shivering and unnerved. I rang the buzzer. I thought of the warm apartment that waited for my return, of all the things that made up my comfortable home. I had barely walked three blocks and I was already looking forward to getting off the street.

nterfaith Sanctuary, a non-denominational shelter in Boise, was a shocking hub of activity compared to the icy quietness outside. Dozens of men and women gathered around tables to share soup and snacks. Some of the residents joked and joshed with each other over dinner, and many of the men stood stolidly along the walls, talking quietly to each other. I was introduced to Jeff, a friendly young man who put me in charge of the phone and medicine cabinet. Jeff was the only regular worker that night, so he was responsible for check-in and assigning beds to the 165 people who were sleeping there that night. He personally said hi to every person who checked in, including a newlywed couple that was traveling from Washington to Texas.

“Guess who proposed,” the wife asked. “Hint: it wasn’t him.”

The husband grinned sheepishly and sauntered away to get some soup. He would return to kiss her goodnight just before bed, when men and women were separated for the evening. Up to this point in my life, like many middle-class suburbanites, my experience with homelessness was mainly comprised of seeing panhandlers outside of grocery stores and city corners. I dropped money in their jars when I could, but more often than not I wouldn’t have any cash in my pocket and I would just walk past.

There are a variety of misconceptions and stereotypes associated with homelessness: the assumption that homeless people are looking for handouts, that they have substance abuse problems, that they are lazy, etc. These are all stereotypes that create an unhealthy image that can hurt good people who are living on the street. According to those working on the inside, what is really needed are things like job and housing coaching, mental health and medical services.

“Ideally, we would have a mental health expert working one-on-one with everyone here,” Jeff told me. “But unfortunately, that would be very expensive.”

On the flip side, there are residents at shelters who have the capability to hold down a job and buy a house, but don’t have the incentives, motivations or skills to make major changes in their lifestyle.

“There’s a couple here, with a couple of kids, and talking to them, they’re very smart, they could get a job, get a place to live, but they don’t want to. This is their home,” Jeff said.

What is it that keeps these people coming back to the shelters? I think I stumbled upon one reason while I was answering phones at the shelter.

When the phone rang, I picked it up and was greeted with a prerecorded female voice telling me that the call was from prison, and that the conversation would be recorded for legal purposes. If I accept these terms, ‘press one,’ the voice suggested. I hesitated, since this was the first call I’d ever received from jail and I wasn’t sure what to expect. I pressed one and waited.

The voice on the other line surprised me. It was jubilant, enthusiastic, excited. The mystery prisoner left a message for his wife, then he asked me to do one more thing.

“I want you to stand up on your chair, tell everyone that (mystery prisoner) wishes them a merry holiday, and a happy new year. Everyone there knows me. Trust me, you’ll get a round of applause.”

Shamefully, although I did pass on a message to his wife, I didn’t complete his second request. Being my first night there, I was too shy to do anything this drastic.

But that is one of the most important aspects of the shelter, one that is often overlooked in news reports and city council meetings discussing homelessness: community. Some of these people don’t have anything or anyone else. The shelter is their home and the people there are their family. Jeff pointed out that many of the residents feel extremely isolated.

“A lot of them go to the library in the morning, stay there all day, and come back here at night,” Jeff said. “This could be the only social interaction they have all day.”

Watching the residents help each other get their beds set up for the night, comradery is clear. Friends wish each other a good night, help sweep the floor and lay out bedding. For some, this is all they have, and they are grateful.

Although for others, it’s the last place they want to be.

As one woman lay down for bed, she was grumbling, “I shouldn’t have to deal with this shit. All these people every night…”

~~~

The challenges facing individuals in the shelter are reflective of larger, growing problems with downtown Boise homelessness, and also across the state.

I’m reminded of a conversation I had with volunteers from Cooper Court, the tent city that sprang up last year behind Interfaith Sanctuary.

“There is no one size fits all solution,” Christina Marfice, a homeless advocate, told me over coffee at The Record Exchange. “A lot of people fall through the cracks.”

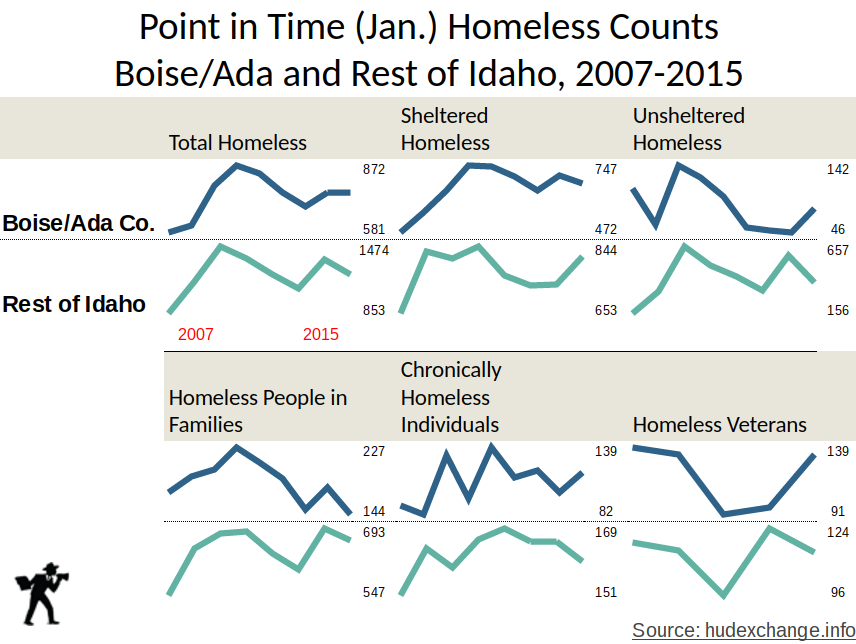

With more than half a million people living on the streets — a number that has been decreasing over the past decade — the United States has experimented with various ways to house the homeless for the past 30 years or more. Ideas have ranged from providing food and medical services, job coaching, counseling and housing options from tent cities to “tiny houses” to traditional shelters. Many studies have shown that the most effective approach to help the homeless is “housing first,” where a place to live is prioritized, regardless of financial difficulties and without prejudice to any social, mental health or substance abuse challenges members of the household may face. Point in time homeless counts are not perfect surveys, as the counting methodology may vary between states and communities, however it is the only national measure available and the the Department of Housing and Urban Development reports these numbers to Congress on a regular basis.The security and stability of a private home helps individuals start to mobilize away from poverty, and keeps them safe from dangers they face on the street. This is ideal for families experiencing temporary homelessness, as it provides a base from which grow. It also requires enough low income housing stock or other housing solutions.

While most cities — including Boise — agree that housing first is the best way to help the homeless, the cost of constructing low-income residences is daunting, and it can be hard to find financial incentives or donors to fund housing projects. This is an issue that has been increasingly prevalent in Boise in the last few years.

While Idaho’s homeless rate is below the national average, the homeless population in the state grew substantially over the last few years, according to the biennial January point-in-time count, which serves as the national homeless census. In fact, between 2013 and 2014, Idaho had the second largest increase in homeless population in the country, behind Nevada. A substantial 18.1 percent increase in homelessness propelled the topic to become one of the most talked about stories in the state, especially in Boise (total homelessness in Idaho decreased 7 percent in 2015).

Faced with a growing homeless population, the state struggled to provide adequate shelter. According to the National Alliance to End Homelessness, in 2013, unsheltered homelessness rose by nearly 70 percent in Idaho, far above the national average (it decreased a small amount in Ada County). In recent years, the homeless population has grown frustrated with the lack of options here. Boise, at times, enforces a no-camping ordinance, which forces the homeless to sleep in shelters, to find shelter deeper in the woods or hills or to face arrest. Currently dismissed lawsuit against anti-camping ordinance.

Those who aren’t happy with these arrangements, which push homeless people toward group shelters, include married couples who aren’t allowed to sleep in the same room, transgender individuals who are forced to sleep in quarters with the opposite sex and anyone who feels threatened or uncomfortable with any of the dozens of other people in a shelter.

It was people like this who decided to find a new place to sleep.

A small community in Boise that didn’t want to stay at the shelters tried to take matters into their own hands at a place dubbed Cooper Court. In an alley behind Interfaith Sanctuary, a non-denominational shelter just off the Connector, these people built their own little tent city, where they could have some privacy in their own makeshift homes. It was a direct violation of the anti-camping ordinance and occupation of a public right-of-way, but much public sentiment was on their side. In the cold months, they had fires to keep warm, tents to sleep in, close access to services, and, most importantly, they had a place to call home.

For many of the Cooper Court residents, staying at the shelter was unbearable. From veterans struggling with PTSD to those with claustrophobia or social anxiety, the shelter can be a living nightmare. Still, it was the natural human instinct to seek out community that led them to converge on Cooper Court. Facing the brutal cold of Boise in winter, this group huddled around fires and brought blankets and makeshift shelters to stay warm in the shadow of the freeway.

Thousands of home-owning commuters could see the tent-city on their morning commute into downtown Boise. Increased visibility opened the door for conversation, and the city had an opportunity to discuss the best way to help the homeless population. Opinions about the best way to help were widely varied, however.

According to a letter from Mayor David Bieter that appeared in the Idaho Statesman, over 1,600 emergency calls were made regarding Cooper Court in 2015. Bieter argued that the encampment had become dangerous, including open fires, unhygienic conditions and increasing criminal activity. After several warnings, the city disbanded the camp on December 4, 2015 and offered residents of Cooper Court one night of shelter and vouchers at the Salvation Army, in addition to referrals to housing and counseling services. The city made it clear that there was room in the shelters for everyone from Cooper Court. Unhappy with their options, some attempted to brave frigid temperatures and sleep in places near the river where they could have some privacy.

Another suggestion came from Andrew Heben, author of Tent City Urbanism, who gave a presentation in Boise in November about Opportunity Village Eugene, a project that he directed. His goal was to show the city that a tiny-home village could be a cheap low-income housing option.

“Over 30 percent of renters spend more than 50 percent of their paycheck on rent,” Heben pointed out, describing how unlucky circumstances could lead many paycheck-to-paycheck families to lose their homes. Once they lose their place to stay, it is very difficult to recover. The tiny homes are meant to provide a short term transition between homelessness and regular rental housing.

According to Jodi Peterson, Cooper Court advocate and fundraising organizer for Interfaith Sanctuary, the city is reluctant to approve a tiny-home village, or other temporary housing because they see it as a stopgap measure. The funding that would be used to build tiny-homes could be invested and saved to later build standard-sized low income residencies.

The most striking moment of the night came after Heben’s presentation. A member of the audience stood up and asked into a microphone, “Is there anyone here representing the city?” There was a pause. “Let me get this right, there’s no one here from the city?” Again, he was met with silence. “They don’t care.”

Heben noted that Boise was the first city where city representatives declined to attend his presentation.

City Communications Director Mike Journee said the city was excited about the idea of tiny houses. However, there was very little data to back up the proposal.

“There may be a place for tiny houses in the larger mix. But camps and tiny houses don’t change the situation. At the end of the day, they’re still homeless,” Journee said.

He pointed out that it would be hard to find a location near services and public transportation where a little village could be built. Also, tiny homes are a relatively new idea. There isn’t a ton of data to support their success.

“Data based decision making is the most effective decision making,” Journee said, explaining why Boise was more interested in the tested and proven housing-first model. Cities such as Salt Lake City have had well documented success when implementing the housing-first model.

At a press conference on February 9, Bieter outlined Boise’s plans for addressing homelessness. The plan has two major parts:

- Single site housing: Bieter made a call for developers to design a structure with 25-30 housing units that will be dedicated to helping the chronically homeless. After these people are off the street, services such as mental health care and financial advising will be offered. The Idaho Housing and Finance Association has set aside $5.75 million in Low Income Housing Tax Credits to help fund the project, and the city of Boise will provide $1 million. The City and the IHFA will also accept donations to help fund the project.

- Scattered sites: This part of the plan may come into effect as early as summer 2016. Up to 15 low-income housing units will be set aside for chronically homeless individuals. Wraparound services will then be provided by CATCH, Inc., and Terry Reilly Health Services.

The city believes there are around 100 chronically homeless people in Boise, and the plan is to house 40 of them by as early as Spring 2017.

“We’ve got to start somewhere,” Journee said. “Hopefully the community will come together to help fill the gap.”

While the community debates solutions, all meet on one common ground: Boise needs more low-income housing. Many people on the street have money from disability and other benefits, but there is nowhere for them to stay. According to Peterson, Boise needs 6,000 low income housing units to meet the needs of the community. The city’s Housing and Community Development Department reports that Boise needs 5,724 new units for extremely low income housing to meet demand.

“Most of these people make eight to twelve hundred dollars a month,” Peterson said. “They just have nowhere to live.”

Homelessness isn’t going to disappear. The shelters will continue to grow more crowded and people will continue to be frustrated until there are more options. The anti-camping ordinance and the disbanding of Cooper Court removed homelessness from the forefront of the public eye, but did not solve the problem. Promises are being made about solutions years from now, but there are hundreds of people — including families — surviving on a day to day basis. Telling someone that they will have a place to stay five years from now does nothing to help them find food and warmth today.

In addition to basic shelter, there is also high demand for medical services. Toward the end of my first volunteer shift at the shelter, I helped provide first aid for a woman. She had been bitten in the finger during a fight, and was dripping blood on the floor. At first, she didn’t want help. She wanted to let it heal naturally.

But a dripping wound in a public space — like the scourge of homelessness itself — requires both immediate band aid measures and equal doses of compassion, public health awareness and a strategy to avoid future bitings.

With some coaxing, I convinced the woman to put a strip of gauze and wrap some bandages around the wound. Though she was reluctant at first, she was ultimately extremely grateful.

“God bless,” she said. “God bless.”

The Blue Review Homelessness Colloquy.

A TBR series on homelessness in Idaho