Election 2020: Challenges and Predictions

Important questions remain for the 2020 election. In this issue of Blue Review, four Boise State political scientists examine issues and tell us what they are paying particular attention to for the remainder of the race.

On Thursday, October 29 at 7 p.m. they will discuss the 2020 elections in a public forum. The public is invited to listen, participate and to bring questions.

Information

Voting Rights

Jaclyn Kettler is assistant professor of Political Science at Boise State University. Her research focuses on American politics with an emphasis on state politics, political parties & interest groups, campaign finance, and women in politics. She earned her Ph.D. at Rice University and her BA at Baker University.

Voting rights is a big issue in this election, and that’s an area you pay close attention to as a scholar. What story will you be keeping a close eye on during election week?

Jaclyn Kettler: Voting rights and election administration are always big stories in presidential election years. However, the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has added to the challenges. It is important to remember we have numerous election systems in the United States since state and local governments run elections. State governments determine the laws governing elections (e.g., voting procedures, voter registration laws). As a result, voting rights and processes vary across states. Knowing that, there are several issues that I’ll be paying attention to as we near November 3.

We’re already seeing higher than usual early voting numbers, resulting in long lines in some states. These lines will be something we continue to watch as we near the election. A variety of factors are likely contributing to these long lines, including technological issues and fewer precincts in some states. Higher than usual enthusiasm for voting and social distancing are also likely contributing to the length of early voting lines. Regardless of the cause, long voting lines can make it difficult for individuals to exercise their right to vote. There is also a concern that voter suppression efforts will keep some individuals from voting.

Another big issue will be the counting of absentee ballots. Absentee ballot requests are likely to be much higher for the 2020 general election than most elections. State and local election officials have been preparing for the increase in mail-in ballots (include increased security measures), but this is likely to cause some additional challenges and problems for them and for voters. According to research conducted by NPR, over 550,000 mail-in ballots were rejected in the 2020 presidential primaries. It will be important for voters to make sure they complete their ballot correctly, sign it as required, use secrecy sleeves when required, and get them returned on time. The deadline for mail-in ballots varies by state with some requiring their delivery by or on Election Day, while ballots must be postmarked by Election Day in others.

State laws determine when election workers can begin processing absentee or mail-in ballots (opening the envelopes, checking signatures, etc.). Some states permit the immediate processing of these ballots or can begin processing them 1-2 weeks before the election. In a special session, the Idaho Legislature passed a bill to allow Idaho election officials to begin processing absentee ballots a week before Election Day. Other states do not allow the processing of mail-in-ballots until Election Day (e.g., Pennsylvania, Wisconsin), which may delay election results in those states. Even though many states allow the processing of mail-in ballots before Election Day, most states do not allow them to be counted until Election Day. Therefore, due to potentially higher voter turnout than usual, there is the possibility it will take longer to count ballots this year than usual.

Polling

Jeffrey Lyons is the School of Public Service Survey Director and an Assistant Professor of Political Science. His research focuses on American politics, specifically public opinion, political behavior, political psychology, and state politics.

A lot of voters are understandably skeptical of political polls, given what happened in 2016. You’re a polling specialist; can we trust polls telling us that certain voters will cast ballots for one candidate or the other?

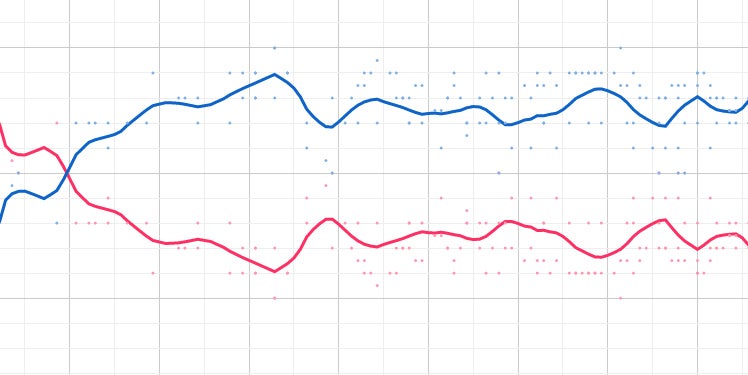

Jeffrey Lyons: A lot of people are skeptical of polling, especially after what happened in 2016. First, let’s take a look at what happened in that election. I would think about election polls in two different groups—national polls and state polls. National polling in 2016 was actually quite good. If you take an average of the polls done in the week before election day, they showed Hillary Clinton with roughly a 3-point lead. She won the popular vote by about 2-points, so the national polls were quite close to predicting the outcome that they were trying to predict. Of course, in our system it is not the national popular vote that matters, but the outcomes of the elections in the states.

When we turn to state polling, the picture gets a bit more mixed. The narrative that the polls got it wrong is true in some battleground states, most notably in the upper Midwest. If we look at the averages of the polls taken in states like Wisconsin and Michigan, they do point to a comfortable Clinton win. After the votes were tallied, Trump ended up carrying both states by less than 1 point. It is important to keep in mind that there were also a lot of battleground states where the polls were generally correct, including North Carolina, Ohio, and Florida.

So, what went wrong in the state polls, especially in the upper Midwest? One of the big challenges with election polling is that we have to predict who is going to show up and vote. Pollsters are forced to make some assumptions about what the group of voters is going to look like, and they usually draw from past elections to figure that out. For example, we know that younger people vote at lower rates than older people, so all else equal, the preferences of older voters are given more weight than the preferences of younger people when we try to predict how voters are going to cast ballots. In 2016, we saw some changes from previous years, making it harder to predict what the group of voters was going to look like. For one, it may be the case that there were not enough white voters with less than a college education in the samples that pollsters talked to, understating the influence of a group that Trump did well with.

Another likely factor was that the turnout rate for black voters fell in 2016, so pollsters were overstating the prevalence of a solidly Democratic group. There are undoubtedly other reasons why a number of state polls were off the mark, but these are some of the big explanations for what took place in the upper Midwest states.

What does all of this mean for 2020? Can we trust the polls this year? I would argue that polls provide the best information about who is winning, but we have to be smart about how to interpret them, and should always keep their shortcomings in mind. Pollsters have made efforts to correct for a number of the issues that arose in 2016, including recruiting more voters with less than a college education into their samples, and polls in the 2018 midterm election were quite accurate.

But, substantial challenges still exist. The percentage of people who respond to surveys when contacted by a pollster is very low, raising the prospect that the people who respond are just different than the people who do not. Some of those differences we know about, and can correct for, but it is the differences that we do not know about or cannot measure that raise real problems. In sum, polls have challenges for understanding who is leading and where.

But, they are usually pretty accurate on average, and they have a lot fewer shortcomings than any other way of trying to know who is leading. Until someone comes up with a better method of understanding the preferences of voters, I will keep paying attention to polls, and putting stock in what they have to say (with a little grain of salt).

Race

Professor Steve Utych’s research focuses on political psychology and political behavior, primarily in American politics. His research interests include language in politics, the development of political attitudes, and how citizens seek out and process political information. Dr. Utych received his Ph.D. in political science from Vanderbilt University and his B.S. in Public Policy from Georgia Tech.

This is a historic election in a lot of ways, especially because an African-American woman is on the ticket, and because of the protests around racial injustice this summer. As someone who studies race, politics, and polarization, what kinds of outcomes do you expect to see?

Steve Utych: Kamala Harris’ position as the VP nominee for the Democrats is certainly historic—not only is she the first Black woman to be nominated on a major party ticket, but she is the first Asian-American person, as well. If Biden and Harris win the election, it would be historic for a host of marginalized groups, who would finally see someone who represents their identity in one of the highest elected offices in the country. It’s easy to underestimate how meaningful this is, since we have recently had a Black man as president, and a white woman as a major party nominee, but it undoubtedly would mean a lot to a lot of people to see a Biden/Harris victory.

As for outcomes related to race and polarization in the election, there is a lot to think about here. Donald Trump has spent his presidency frequently refusing to denounce white supremacist groups, and hasn’t really shown much support for traditionally marginalized groups in society. He has routinely insulted Latino/a immigrants, has refused to take seriously Black Americans’ concerns about racial injustice and policing, and has used racist language to describe the COVID-19 crisis. I struggle to think of a marginalized group in society he hasn’t done something offensive towards. If Trump is re-elected, I would certainly expect to see protests and demonstrations. I imagine those would be akin to the ones we saw, typically led by women, in 2017, or the ones we saw related to police violence and racial injustice this summer. That is, I expect to see large demonstrations, probably larger than after the last election, that are largely non-violent in nature.

If Biden wins, we expect to see a different reaction to the election. I hope that a Biden victory would lead to a generally peaceful transition of power, but given that Trump has, at times, seemingly voiced approval for white supremacist militia groups, I don’t feel we can be certain those groups wouldn’t take some action. They have organized armed protests against various state level COVID-19 restrictions; although they have thankfully been mostly nonviolent up to this point, they do serve to intimidate. One such group had a significant number of members arrested for plotting to kidnap Gretchen Whitmer, the governor of Michigan. I think it’s also clear that white supremacist groups have served as agitators during the summer protests against racial injustice, so we could see these groups in action even if Trump does win the election. White supremacist violence is a big problem facing our country, and I worry that these groups would not handle a Biden victory well, especially if urged on by Trump.

Of course, all of this pre-supposes an election outcome that is clear and accepted, which is not assured. It’s one thing if the election is simply too close to call, and takes a significant amount of time to count and recount votes (think of the 2000 election in Florida, which I think most folks accept was within a margin of less than 1,000 votes). This might be a situation where the election result is ambiguous, and may be decided in court challenges, because the margin itself is small and potentially ambiguous. This is something I don’t see as entirely likely.

However, Donald Trump has repeatedly refused to say he will accept the results of the election, and has consistently spread lies about voter fraud and election rigging, especially as it relates to mail-in voting, which will be higher this year due to COVID-19. Vice President Mike Pence also refused to say he will accept the election results, and prominent Republican senators like Lindsey Graham have openly called for the election to be decided by the courts. It appears the conservative-majority Supreme Court may also endorse deciding election results before all votes have been counted as well, in favor of a quick, clear outcome.

This behavior could be perceived as anti-democratic, and its aim is to decrease the legitimacy of a clear Biden victory. If Trump, Pence, and their allies in Congress refuse to accept a Biden victory on baseless claims of voter fraud, this could throw the country into real chaos, especially with the possibility that the Supreme Court could rule in favor of Trump’s illegitimate claims. I don’t know what would happen in this instance, and, quite frankly, I hope not to find out.

Congressional Elections

Charles R. Hunt is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at Boise State University. His research focuses primarily on the U.S. Congress, congressional elections, partisanship, and representation. He has a Bachelor’s degree in Political Science from Brown University, and a Ph.D in Government and Politics from the University of Maryland. Prior to graduate school, he worked as a political consultant and communications professional in Providence, Rhode Island, where he grew up.

You focus especially on congressional politics. There are so many states this year that are in play in ways they never have been before. Is there a high-profile race that is really interesting to you? What about a race that’s not getting as much attention?

Charles R. Hunt: It’s tough to know where to start, but I’ll do my best! The way I see it, there are a couple different tiers of Senate races that are worth looking at.

First, it’s absolutely true that there are a number of states in play this year that have no business being competitive. Currently, we’re seeing surprisingly tight races in Montana, Kansas, South Carolina, Texas, and Alaska. South Carolina is of particular interest because the incumbent running for re-election is Senator Lindsey Graham, who has been the target of a great deal of Democratic ire over the past four years. Of these states, Graham is probably the most likely to get knocked off by a Democratic opponent, though our neighbor Montana also features a very close “Battle of the Steves” (Democratic Gov. Steve Bullock vs. incumbent Republican Senator Steve Daines). If either of these races swings in the Democratic direction, then Republican control of the Senate is almost certainly doomed.

Winning these races, however, could just be icing on the cake for the Democrats. Even if incumbent Democratic senator Doug Jones is unsuccessful in Alabama (as currently appears likely), the Democrats remain in a strong–but by no means certain—position to pick up the number of seats necessary to win back control of the Senate. The most likely route there is through North Carolina, Maine, Colorado, and Arizona, all of whom feature incumbent Republicans who have trailed in the polls by decent margins for most of the year. Even combined with a loss in Alabama, these four seats would give Democrats the majority in the Senate.

But even beyond this, there are three other Republican seats in the traditionally redder states of Iowa and Georgia that could seal the deal even further. Iowa has been a surprise option for Democrats, whose nominee Theresa Greenfield has held a small but consistent lead over incumbent Republican Sen. Joni Ernst in recent weeks. The Georgia seats in particular will be a bellwether to look out for on election night(s), not just for the Senate, but for the presidency, where Joe Biden’s odds of winning appear to be roughly 50/50. Without these two states, Donald Trump is very unlikely to be re-elected, and Republicans even less likely to hold on to the Senate.

The race for majority control of the House of Representatives is likely to be much less dramatic. Many of the seats the Democrats won in 2018 “Blue Wave” are what we would call “frontline” districts—those that were won by Donald Trump in 2016, or only narrowly won by Hillary Clinton. But Democrats’ continued dominance in suburban areas means that enough of these seats are very likely to remain in Democratic hands, making Republican efforts to take back the majority nearly impossible; in fact, the Democrats are as likely as not to pick up more seats than they lose, despite their already-huge majority. If the President truly believes his prediction during the last debate that Republicans will win the House, he’s likely to be disappointed.