KayCee Downey (she/her) is a city planner and public historian. An alum of Boise State University, KayCee earned her Masters of Applied Historical Research in 2017, where she focused on gender and political history. Today, her interests lie in cross-disciplinary solutions to everyday problems, in which she believes an understanding of the past always has a place.

Idaho and agriculture go together like mashed potatoes and gravy. French fries and ketchup. Tubers and, well, Idaho. According to the 2017 Census of Agriculture, the most recent data on agricultural land, Idaho has a total farm size of 11.7 million acres. Despite farmers not actively using all 11.7 million and the fact that the number of agricultural acreages is decreasing at a substantial rate, that is still a lot of land that needs planted, managed, and harvested each year.

And a lot of land needs a lot of labor.

Governor Brad Little signed H.B. 373 on March 10, 2020. The bill expanded the agricultural work program within the Idaho Correctional Industries (ICI), an offender training program. A reiteration of past bills, with the Agricultural Work Program (AWP) first established in 2015, it essentially allowed the continued contracting out of prison labor to agricultural employers. Implemented at South Idaho Correctional Institute, South Boise Women’s Correctional Center, and St. Anthony Work Camp as of December 2020, the AWP contracts out workers for planting, harvesting, packaging, and sorting of fruits and vegetables. It provides (some of) the labor used for Idaho’s agricultural acreage and the foods that acreage produces.

Well before the Agricultural Work Program, however, Idaho employed a different group of incarcerated individuals for farm labor – Japanese and Japanese-American internees from the Minidoka concentration camp.[1]

The Boise State School of Public Service will co-host the Minidoka Civil Liberties Symposium at 11 a.m. MT on January 17, 2021.

Watch the symposium on the Japanese American Memorial Pilgrimages YouTube channel

When Farmers Head to War

World War II saw an increased demand for food – to feed the Homefront and the servicemen and women overseas – while at the same time creating a farm labor shortage in the United States. Over twenty percent of the country’s workforce was in the military. That workforce included farmers. A letter sent to the head of the Division of Farm Population and Rural Welfare, dated April 13, 1942, indicated farm employment in the Pacific States was down by fifteen thousand workers. Farmers had to find alternative workers to prevent crops from literally rotting in the fields.

One alternative workforce was the Japanese and Japanese-Americans that had been forcibly removed from the West Coast and relocated to concentration camps. One such camp was Minidoka, located in South-Central Idaho and opened on August 12,1942. From the beginning, farmers around Hunt, Idaho and throughout the region (including Utah and Montana) looked at the new arrivals as potential farm laborers.

Before the Minidoka camp was even open – three months before to be exact – the Idaho Daily Statesman announced that 1,000 Japanese workers were approved to work in Idaho to thin sugar beets on “some 19,000 acres in Twin Falls, Cassia, and Minidoka counties.” The article went on to say the workers were arriving with short notice, within a week to ten days, in order to save the crops. ‘Japanese Leave Idaho Camp to Work on Farms,’ published in the September 16, 1942 Idaho Daily Statesman, read: “To save food-for-freedom crops threatened by the wartime labor shortage, hundreds of Japanese volunteer workers from Minidoka war relocation center are moving into the sugar beet, potato and onion fields of Idaho and Montana.” Three months after Minidoka opened, the Minidoka Irrigator announced that more than 2,100 workers from the camp had helped harvest the sugar beet crops, saving part of the 13 million tons of beets pulled, piled, topped, and loaded overall in the region.

The Life of Incarcerated Farm Laborers

In ‘Life in Onion Fields is No Bed of Roses’ by Tadako Tamura, published in the October 7, 1942 Minidoka Irrigator, the reader gains a better understanding of daily life for the Japanese and Japanese-American farm workers.

This is not an easy life. It’s a strenuous day. It starts somewhere between 4:30 and 5 a.m. with the clanging of coal in ranges and the smell of coffee blending for the eye-opener. By 6:30 o’clock, 40 of us huddle in an open truck to be transported to the onion fields – some 30 minutes’ drive away.

Some of the farm worker lived at Minidoka, with their employers providing transportation every morning to the fields where they would work. These workers had to show appropriate permits and approvals every morning as they exited the concentration camp, walking through the barbed wire fences as the rest of their family and friends stayed inside. The commuting workers usually left in large groups, picked up or assigned to drive buses to and from the fields. This was not the norm, however. Most of the Japanese and Japanese-Americans were housed by the employers outside of Minidoka. These locations varied. Depending on the work they were doing and the size of the farming operation, some were housed in outbuildings on a farmer’s property while others laid down their heads at constructed “labor camps” that served surrounding fields (such were the accommodations for Tadako Tamura).

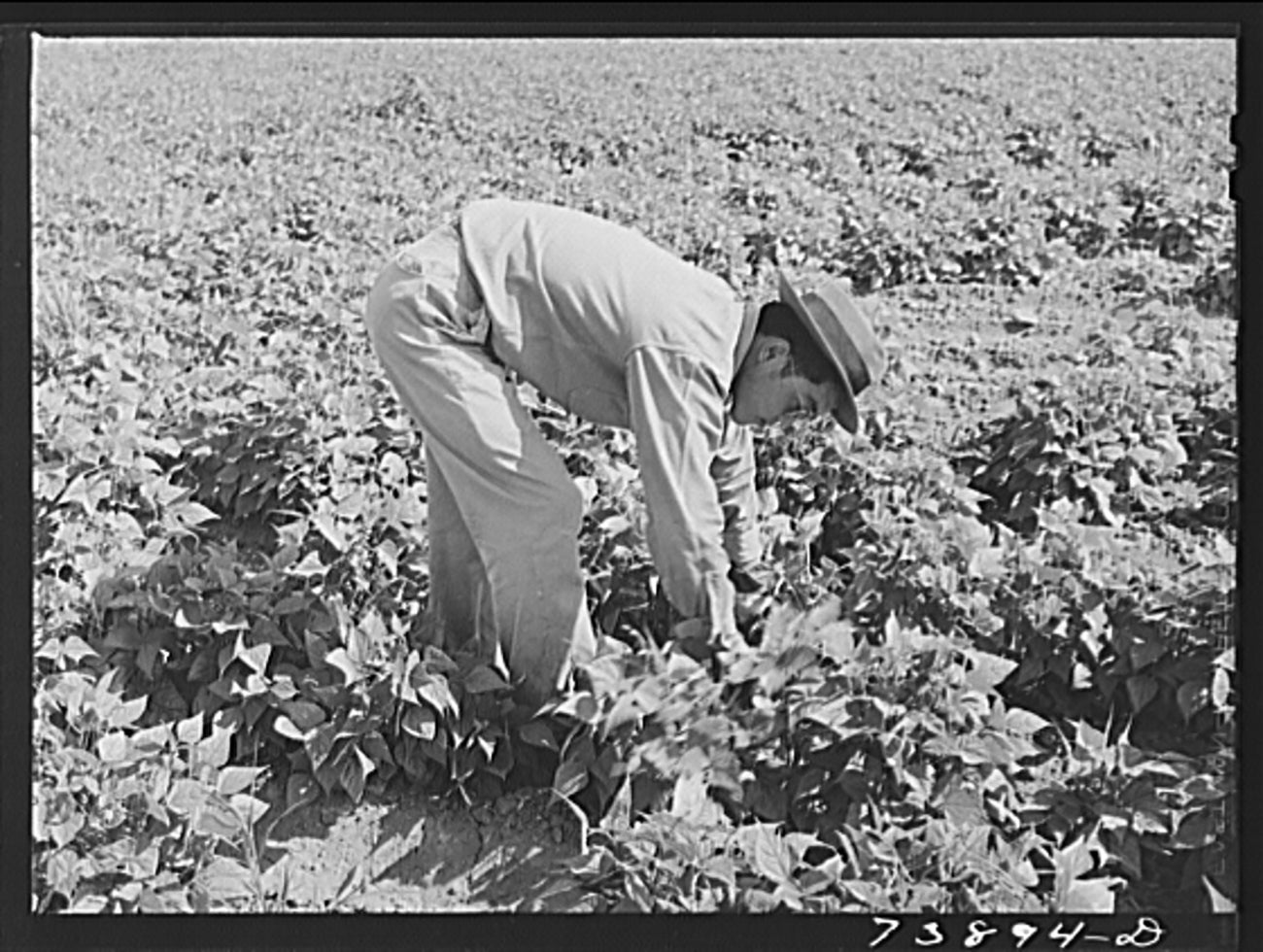

With the dawn still to streak the skies, we gather about a field bonfire, fed by dried woods, trying to warm ourselves. Then in groups of twos and threes, we attack the onion fields leaving countless sacks behind us brimming with round onions. Some of us crawl on our hands and knees while some prefer to stand with bodices bent double and flexing with the rhythms of the work.

Farming equipment was scarce and the fuel to use it even more so. Tractors still owned by Japanese and Japanese-American farmers – now in storage due to their incarceration[2] – were requested nationally to be sold or lent for farming efforts, the appeals advertised in various concentration camp newspapers. Despite this call, however, most of the internee farm laborers did not have access to the equipment. Instead, they worked with their hands and knees and backs.

When 5 p.m. comes around, we are ready for the hot shower that awaits us at the FSA camp – our one pleasure after a hot and grimy day…. But no rest even after the showers, for dinner must be prepared. Many jump off the truck at the grocery store about four blocks away to buy food.

Dinner is usually prepared in small groups with ours numbering six. Dinner is ready about 9 p.m. Eating and washing the dishes pass the time and it is 11 o’clock before we can go to bed. Of course, tomorrow’s lunches must be put up too before hitting the hay. Then, it’s pull the covers and drifting off to sleep. It’s a hard grind but we like it – this working with the good earth.

Such a life was experienced by thousands of Japanese and Japanese-American workers. A June 17, 1942 Idaho Daily Statesman article – ‘White-Collar Men, Japanese Saved Beets’ – explained the employment of internees to the white population, many still unsure of the new laborers. Most of the workers were farmers before leaving their homes. They were not under armed guard but did have constant surveillance by Deputy sheriffs assigned to various labor camps. Movement was restricted. Visitors were rarely allowed.

The Good, the Bad and the Discriminatory

One Herbert Tiegs of Nampa, Idaho wrote to the Minidoka Irrigator on December 19, 1942 to share praises of his Japanese and Japanese-American farm laborers. “The fifteen workers and one chaperone who signed my contract and fulfilled it, satisfied me so much that I have decided to write you.” His crew was made up of all women, and together topped over 950 tons of beets in twenty days – earning about three dollars a day.

In fact, their hard work had caught the attention of the Amalgamated Sugar Company, who took movies of the women topping and loading the beets for industry propaganda, and invited them on a tour of the factory. In the end, the farmer was happy to have met these women, “not only because they helped save a large part of my crop, but because the friendship that has been formed will help to strengthen our country to unity again.”

Tiegs appears to have viewed the labor from the concentration camps as a means to promote not only the ongoing war effort, but also to tackle the racial and xenophobic tensions present in the country and highlighted in the state due to proximity. The cheaper labor, of course, was a bonus. Most farmers, however, focused on the numbers, not the people.

Another letter to the Minidoka Irrigator, written by five local farmers, illustrates the emphasis on the results and not on the workers themselves. “During the season they picked 91 acres of potatoes which average about 150 sacks per acre…They topped 99 acres of beets which yielded approximately 22 tons per acre.” Gurling, Bauer, Bickard, and two Griffiths “sincerely hoped that in the future a program may be worked out between the farmers of Southern Idaho and the War Relocation Authority so that this relationship may continue.” However, the sense that the desire was rooted in profits and efficiency cannot be removed from the sentiment. Neither can the assumption of, and desire for, continued incarceration.

The inclination to view the Japanese and Japanese-American workers as tools – rather than individuals who had been ripped from their homes and forced to take up farm labor for income and to escape the confines of incarceration – can be illustrated in a dispute between the Shelley Beet Growers Association and eight young farm laborers.

As played out in the Minidoka Irrigator newspaper – with letters from the association chairman Arvie Miller, letters from the Japanese-American young men, and paper editorials – the dispute came down to three issues: (1) the young men were not provided the acreage of potatoes that the contract claimed, (2) the yield was less than what it was supposed to be, (3) the housing was not what was promised, and (4) the young men were not making enough money (a fifth was added by the chairman, who claimed the boys quit because “they were not having fun”).

Answering the four charges, Miller claimed the young men only gave five days’ notice before quitting, averaged five dollars a day, left six of the potato crops unharvested, and had not touched fifty acres of beets. While the young men were promised 200 sacks of potatoes an acre, they were averaging 185, which he felt was fair. As for the housing conditions? They were “equal to the average.” Clearly, the issue was with the workers and not the conditions. Miller went further to sully the names of the workers, stating: “I do not think it is wise to allow a group of boys as those to come out to do a man’s job.”

Ranging from 16 years of age to 21, the workers felt the above claims were groundless. They were justified in failing to complete their contracts. In the fourteen days they worked, they were averaging 120 sacks of potatoes an acre, not the 185 Miller stated and far from the promised 200. Furthermore, they had agreed to being paid three cents a sack, which Miller had assured them was the prevailing rate. Afterwards, speaking to other workers, they found the average wage was ten cents a sack. As for housing?

The three room house was a copy 9’ by 21’ shack, a canvas tent, and a discarded, floorless chicken coop. The wood cook stove was placed outside by necessity since there was no other available space. No facilities of any kind were furnished for laundering. A large tin tub was provided, but the materials which were promised us were not given us – the only practical solution to bathing being to convert the tub into a Japanese style bath.

And they were not lazy, the young men argued.

In case there may be any doubt in your mind concerning the seriousness of our desire to work and to aid in the present farm labor shortage, we are now working under contract in Gooding, Idaho. Thus far, we have harvested several acres of sugar beets and potatoes. The work is by no means easy or ‘fun,’ but we enjoy putting 9 to 10 hours a day for an employer who treats us decently and fairly. And we enjoy living in a friendly environment where we need have no fear.

Such public slandering by a large association against eight young men, whether the arguments of the men against them were true or not, shows a lack of empathy. If the claims were in fact true – with a small shack, tent, and chicken coop counting as equal to the average food and housing– the work these young men performed was clearly undervalued. It also reflected the general perception of the Japanese and Japanese-American farm laborers. These workers were just a means to an end, who should feel lucky to have any work, at any pay, in any conditions.

Dislike of the workers was common, but the need of the work prevailed. A poll of Utah citizens on off-project jobs for Nisei (first generation American citizens whose parents immigrated from Japan), conducted by the Western Institute of Public Opinion, found that 65.6% of the population approved of the work. Of the farmers polled, however, only 59.6% approved, raising questions about the farm labor shortage and their views of the workers they were hiring. Comments of the poll highlighted the distrust of workers, but also the economic drive behind employing Japanese and Japanese-Americans. “We need their help if [they are] loyal.” Emphasis my own.

Conclusion

The use of incarcerated workers for harvesting and other farm work has a long history in Idaho and the surrounding Northwest, existing long before the Minidoka concentration camp and long after. However, the use of interned Japanese and Japanese-American men and women and today’s use of the Agricultural Work Program largely came about the same way. According to ‘Farmers Ponder Labor Problem’, an article published by the Idaho Daily Statesman on September 18, 1943, not enough Mexican laborers were being sent to Idaho. They had collectively requested 1000, but only 250 had arrived, putting more pressure on the labor shortage. Similarly, much of Idaho agriculture relies on migrant workers, with the workforce impacted by reduced immigration, changing worker visa programs, political climates, and now, a global pandemic.

Whether migrant workers, prisoners, or internees, farm labor is too often about the needed labor, not the individuals. While H.B. 373 allows Idaho Correctional Industries to contract out incarcerated individuals for agricultural work, the bill, nor any other law in Idaho, does not provide the workers protections, such as worker’s compensation or disability. Yet, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, agriculture ranks among the most hazardous occupations. Farm laborers work in extreme temperatures for long hours, performing physically demanding tasks. They are constantly around dangerous equipment and chemicals. As such, concerns have been raised from various advocacy groups about worker safety and support, in both Idaho and the nation as whole. Though not needed to be said, internees did not have protections either.

Another parallel is pay. The incarcerated Japanese and Japanese-American farm laborers, paid pennies per sack, averaged $12 a month (though many made much less). Caucasian farm workers at the time averaged $48 a month. The ICI states that they negotiate wages to avoid prisoners being used as cheap labor, thus displacing non incarcerated workers who could not compete. However, the going rate is not readily found. A 2017 Spokesman Review article featured an interview with the owner of Symms Fruit Ranch, which had a contract with ICI for a billing rate of $8.05 per hour. Above the federal and state minimum wage of $7.25. Yet the Spokesman Review reported that incarcerated workers were keeping only $1.61 per hour. The rest of their pay went into restitution funds, court fines, and overhead costs for the work program itself.

Despite the ever-decreasing acreage of farm land, it would be impossible to imagine Idaho without agriculture. But the potatoes, onions, sugar beets, and other staples of the state do not get harvested, loaded, and otherwise processed without labor. Contemporary prisoners of the state and Japanese and Japanese-American prisoners of the nation, two groups separated by over a half century, yet working within the same inherent power dynamics that seem to be as American as sweet potato pie.

[1] This article uses the term “concentration camp”, rather than the more common “internment camp”. The term was consciously chosen to reflect contemporary campaigns to reframe the incarceration of Japanese and Japanese-Americans and avoid othering euphemisms. Readers are encouraged to visit the terminology page on Densho.org, a grassroots organization that aims to preserve and share history of the WWII incarceration of Japanese Americans. However, for clarity, the term “internee” is still used throughout the report to signify individuals who were incarcerated in these camps, with the author willing to update their phrasing as terminology evolves.

[2] Japanese and Japanese-Americans forcibly relocated out of the west coast lost most of their possessions. Some families were fortunate enough to have friends willing to store some of their items or were able to organize other means of long-term storage before being sent to temporary assembly centers. For further reading, the author once again recommends Densho, this time for their article titled ‘Sold, Damaged, Stolen, Gone: Japanese American property loss during WWII’.