Chase Johnson is a Research Associate at Boise State University’s Frank Church Institute. He researches Russian Affairs in addition to assisting the research of the Frank Church Chair of Public Affairs. Chase has degrees in International Relations from Boise State and Johns Hopkins Universities. He served in the U.S. Peace Corps in the Republic of Georgia, and later returned as a researcher at Tbilisi State University. He also served briefly in economic affairs at the U.S. Embassy in Moscow and worked on NATO Affairs for the Defense Department.

In the late eighteenth century, Russian statesman Grigory Potemkin built facades of extravagant looking buildings to place in villages. He also employed people to pose as happy residents. When Empress Catherine II (also known as Catherine the Great) traveled the countryside, she was given the impression the peasantry was thriving and prosperous. While certain aspects of the story are likely apocryphal, the adjective “Potemkin” lives on to describe extravagant facades to hide deep system problems and is perhaps the world’s most potent trope to describe extravagant political misdirection.

The original concept of the Potemkin village was to avoid speaking truth to Russian power. Today, Russia’s presidential elections are Potemkin horseraces, meant to convince the world that the country is a functioning modern democratic state. In a recent episode of the Power Vertical Podcast, Russia watcher Brain Whitmore explained that the most important thing to keep in mind while watching Russian presidential elections is not the competition, but the idea that it is all a piece of Kremlin theater. To best critique this play, first we must meet the cast:

VLADIMIR PUTIN – THE NEW CZAR

Current president Vladimir Putin can stand for his fourth term thanks to some clever constitutional gymnastics. Previous versions of the constitution limited a president to two four-year terms. Putin interpreted this as two “consecutive” terms and endorsed Dmitry Medvedev’s presidency from 2007-2011. He then considered the slate wiped clean and that he was eligible to return to power. Under this logic, and with presidential terms extended to six years, his potential time in office reaches until 2024. Earlier this year, he noted that he would like to hold office until he dies.

Putin is legitimately popular by every measure. He rescued Russia from chaos in the 1990s, and has kept the right people rich and powerful. If he stood in a free and fair election with an open media, he would likely still win. His political party did lose municipal seats in Moscow this year, but these are meaningless in the Russian power structure when their work can be undone by the Kremlin at a moment’s notice. The real center of Russian power still unequivocally rests with him.

KSENIA SOBCHAK – THE REALITY TV STAR

By far the biggest surprise in the campaign is the announcement that socialite and journalist Ksenia Sobchak will run as an independent candidate. She is young, more liberal, and embraces Western ideas in her politics and lifestyle. She was a prominent figure in the 2012 Bolotnaya Square protests following Russia’s parliamentary elections. However, she is also Vladimir Putin’s goddaughter and very close, at least socially, to the inner circle of the Kremlin.

If the Russian election is theater, is she being cast as a false antagonist? Is she in the race to offer a false sense of competition and to show the world that pro-Western candidates do have a space? If so, she would be the perfect actor to play the role. If this was an independent move by Sobchak, however, she could be trying to give a new face to Russian opposition. Despite attracting several prominent political operatives, she has few policies to speak of, save for being anti-corruption. This is a logical stance for a Russian opposition leader in the time of Putin, but in reality it is just a platitude. Putin himself is anti-corruption, but the issue has become one of tribalism. More often, anti-corruption figures are seen only as advocates for “their brand” of corruption. If this candidacy is indeed legitimate, it needs policies that speak to local issues Russians face, such as poor public health and the lack of potable drinking water. If this is where the operatives take her, and if this is not a Kremlin cutout, Sobchak’s candidacy could potentially be a curve ball for Putin.

VLADIMIR ZHIRINOVSKY & GENNADY ZYUGANOV – THE PERENNIAL FIREBRANDS

These two men are mainstays in Russian presidential elections. Vladimir Zhirinovsky is a Russian nationalist firebrand straight from central casting. One can find a laundry list of his extreme positions, but perhaps none more evocative of his radicalism than when he called on Putin to drop a nuclear bomb on Istanbul in retaliation for Turkey downing a Russian fighter jet over Syria. He is a favorite of the minority of Russians who actively seek a new overt empire and disapprove of Vladimir Putin because he is not hawkish enough.

As for Gennady Zyuganov, there is perhaps no better connection to Russia’s Soviet legacy than he and the Communist Party. He had a real shot at becoming president instead of Boris Yeltsin in the 1990s. Now he and his cohort have a tacit understanding with Putin’s circles that they can proclaim nostalgia for the Brezhnev-era Soviet Union in exchange for marching lock-step with Putin’s policy agenda with their votes in the Duma. These two candidates are in every election, but nothing more than showpieces.

ALEXEI NAVALNY – THE CANDIDATE WHO CANNOT RUN

Russian law, like many other countries with developed legal systems, states that convicted criminals cannot run for elected office. Such a law is only effective when the country has an independent judicial system, which Russia lacks. On February 8th, Navalny was convicted of embezzling money through an obscure deal on timber purchases with a state-owned Siberian company. We will never know if this was a setup or if Navalny is actually guilty of petty corruption, but if the truth comes out, neither outcome should be surprising. However, the court decision did end his presidential campaign before it started.

Navalny is the perfect window into the state of the Russian opposition. They are scattered, incompetent, and an effective argument for the Putin regime with the Russian people. Navalny’s primary mission is to get Putin and his cohort out of office. Few details have been offered in terms of what his theoretical government would look like, and his grasp on issues leaves a lot to be desired.

Western Observers must learn to de-couple their analysis of Navalny the politician and Navalny the activist. As an activist, he is incredibly effective. The most recent round of protests were thanks to Navalny’s work flying drones over the mansions of the Russian elite to show what they have bought with the money garnered from their graft. Navalny would be best served by muting his personal electoral ambitions and continue to keep hitting Putin from his peripheries. Doing so would be an ironic but potentially effective way to change the status quo in Russia.

THE STATE OF THE RACE

With the play cast, we must next look at the set and the props. We can count on Western institutions to call out the legitimacy of the vote as they did in late 2011. Yet, polling shows that Putin is on sure footing even if the vote were to be allowed to go forward without interference.

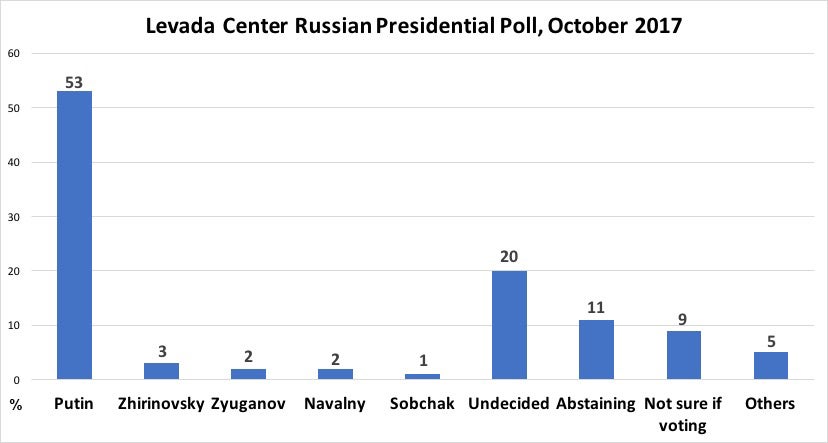

One of the most useful windows into Russian politics is the independent think tank and polling company, The Levada Center. Their work has stood the test of Western peer review and offers valuable insight into broad-based public opinion across Russia. As of their most recent polling, Vladimir Putin should feel confident in both his chances for a fourth term and the level support of his agenda. 57% of respondents want to see Putin continue to serve as President, while 11% want someone new who will continue Putin’s agenda. Only 18% of Russians want Russia to go in a new direction with a new leader.

Without referencing individual candidates, a separate line of questioning asked respondents about the government’s policies. 42% wanted policy to remain the same as it is now, while 34% wanted the government to be “tougher” towards the West. Only 12% wished the government would become more liberal and more Western. This is not good news for Navalny and Sobchak. The majority of those who do disagree with Putin only want to see someone more hawkish in leadership. These numbers offer a sobering note for those who hope for a future liberal Russia. Part of this public opinion is undoubtedly driven by the Kremlin and its media narrative; after all, Putin’s consolidation of Russian media and its narrative continues to ensure his popular support. Given the polling numbers it is not provocative or without basis to call Putin the “moderate” candidate in these elections, even if his policies, by global standards, are anything but.

CAN THE WEST GIVE RUSSIA A TASTE OF ITS OWN MEDICINE?

The United States recently had a presidential election where one candidate had a similarly substantial lead in the polls. This therefore begs the question: Could the West potentially intervene the same was that Russia did in 18 elections in previous years. While it is unlikely that Western intelligence agencies would make such a provocative move, it makes for an interesting thought experiment.

Putin himself would say that this has already happened, only the West called it “democracy promotion.” Putin has labeled Western NGOs as “undesirables” and passed laws against foreign funding on non-profits in Russia while openly blaming them for discord. It is these groups that Putin points to as the cause for protests in 2012 and likely the genesis of the idea to intervene in America’s 2016 presidential race.

In terms of intervening in the Russian 2018 election, The United States, NATO, and Five Eyes all have the capability to run sophisticated influence campaigns and intelligence operations abroad. If a hawkish Westerns leader were to pull the trigger on Twitter trolls and botnets, could we see similar discord this March? In short, no.

A major hindrance in a potential campaign against the Russian 2018 presidential election is that there are no ports of entry for such an operation to take hold in the country’s political discourse. There is no Russian equivalent of something like Russia Today, where Washington can insert its desired narrative directly into the Russian media market. Also, Russia has passed rather draconian laws governing information, requiring the onshoring of social media data on Russian servers, and forcing any blogger with 3,000 or more followers to register as a media outlet, and thus subject to censorship.

With no thought given to personal freedom or civil liberties, defending against influence campaigns is easy, and Putin has built a nigh impenetrable wall around Russia’s information spaces. Even if the United States were to deploy the best cyber warriors and Twitter trolls, it would be unlikely to have any effect on the election outcome.

ENJOY THE SHOW AND ITS PREDICABLE ENDING

Viewing the Russian election as a Potemkin horserace lets us dispense typical political analysis that would normally go with election observation. However, it does not make discussion of this event in Russian history any less fruitful. Modern Russia is a surreal and cynical counter-example to the notion that large-economy states need to also advance democracy and social justice. The country is the instrument of its leader and Putin is incredibly effective at using its institutions to achieve his desired personal ends. It may be attractive for Western observers to try and predict Putin’s downfall or the neutering of his power, but any who presume to do so should read media from 1989-1990 and see just how many people predicted the end of the Soviet Union in 1991.

In short, Putin will win another six-year term as president of Russia. He will continue to pose a threat to Western institutions and encourage radical populism from the people of Europe and the United States. There is no calculus that can form a coalition to push Putin to a more sympathetic position towards the West.

Watching the Russian elections will likely be akin to going to see the next Marvel superhero movie: a stunning set piece with incredibly dynamic characters and a wholly predictable ending. It will not win any Oscars for original screenplay, but it will be fun to watch nonetheless.