Armed Trump supporters outside of Republican National Convention in Cleveland. Matt Shiffler Photography / Flickr (CC BY-NC-SA2.0)

Beyond political metaphor, GOP candidate raises specter of violence

At an Aug. 9 rally in Wilmington, N.C., Donald Trump warned his supporters of the inherent danger in allowing Hillary Clinton to appoint a justice to the Supreme Court: “Hillary wants to abolish, essentially abolish, the Second Amendment… If she gets to pick her judges, nothing you can do, folks. Although the Second Amendment people, maybe there is. I don’t know.”

These remarks were widely interpreted by Trump’s critics as a call for violence against Hillary Clinton. While Trump and his campaign roundly denounced this interpretation — they wrote it off as another example of biased media coverage and explained it as a call to mobilize Second Amendment advocates — many saw this denunciation as just another attempt to walk back his intentional but inappropriate comments, one of many similar walk backs this election cycle.

Here’s why Trump’s comments were so easily construed as an attack on Clinton and so difficult to dismiss as a misunderstanding. First, Trump’s comments are consistent with a trajectory of escalating calls for violence against Clinton among members of the GOP. Cries of “Hang that Bitch” have become commonplace at Trump rallies. But these calls aren’t limited to attendees at rallies; they also come from officeholders and high-ranking campaign advisers. A few weeks ago Rep. Michael Folk, a member of West Virginia’s House of Delegates, tweeted: “@HillaryClinton You should be tried for treason, murder, and crimes against the US Constitution… then hung on the Mall in Washington, DC.” One of Trump’s own advisors, Al Baldasaro, called Clinton a “piece of garbage” and suggested that “Hillary Clinton should be put in the firing line and shot for treason.” Add to this New Jersey Governor Chris Christie’s bizarre convention speech and Ben Carson’s attempts to link Clinton to Lucifer, and this rhetoric seems more reminiscent of the Salem Witch Trials than a modern Presidential contest. In each of these cases, Trump has offered either tacit acceptance of this kind of dehumanizing rhetoric or outright praise.

Second, Trump’s comments are hard to dismiss in light of the nation’s ongoing struggle with gun violence and domestic terrorism. The Gun Violence Archive reports 239 mass shootings in the first 227 days of 2016, and police shootings are on the rise. Some have called Trump’s comments a dog whistle to violence against Clinton — a coded or ambiguous statement that will fly under the radar for many voters but register as a literal call to arms among a small, targeted group inclined to see gun violence as a legitimate form of political expression. There are clear parallels between this kind of rhetoric and the murder of British MP Jo Cox by a white nationalist earlier this summer. This incident warns of the connection between extremist rhetoric and political violence.

Violence is not a new feature of presidential campaigns, or political campaigns more generally, but it has typically been engaged through metaphor. For example, the “political campaign as war” metaphor is ubiquitous. The term campaign itself has its origins in military strategy, and references to the candidates’ war rooms, discussion of candidates air wars versus ground games, and an emphasis on battleground states all speak to how the war concept permeates public discussion of the modern political campaign. Jackson Katz, author of Man Enough? Donald Trump, Hillary Clinton, and the Politics of Presidential Masculinity, notes that war metaphors are frequently intermingled with sports metaphors in media coverage of campaigns. Sports metaphors tend to relate political contests to violent sports; for instance, presidential debates are often cast as boxing matches. Candidates are praised for their pugilistic stances and heavyweight status. See also Meredith Conroy’s “Feminize your Opponent” in The Blue Review.

It’s important to recognize that these metaphors offer a highly stylized form of violence. Historically, war imagery in campaigns has spoken to the concept of an orderly, sportsmanlike “gentleman’s war” and not guerrilla warfare. Similarly, the boxing match metaphor implies that there are rules to the contest and that participants are engaged in a well-structured competition between (relatively) similarly matched opponents. Implicit in these metaphors is also the idea that there are penalties for breaking the rules or for introducing outside factors; a match can be declared no contest, war crimes can be punished by the international community. All of this carries forward, creating norms or expectations surrounding the contest, resulting in a kind of contained and stylized violence that is socially sanctioned. Katz notes that these kinds of metaphors are so commonplace that they barely register; they are “nearly invisible, even to cultural critics, precisely because they are such a part of our daily speech that they ‘fly under the radar’ of cultural consciousness (p. 51).”

While Trump’s comments may still “fly under the radar” for some voters, they represent a disturbing departure from these more sterile manifestations of violence in American political campaigns. Trump’s rhetoric suggests there are no rules; it marks a shift from gentleman’s war to domestic terrorism. By promoting “extra-mural” violence against his opponent, Trump abandons the relative safety of violent metaphor and enters more dangerous territory. Trump has been praised by his supporters for his literal speech — telling it like it is, no matter how unpopular the sentiment might be. His call on Second Amendment supporters, though seemingly vague, speaks much more literally to the possibility of political violence as a legitimate political strategy — either in the form of political assassination or armed insurrection. It speaks to the anti-government, pro-militia mindset that attracted many supporters to Trump in the first place.

Trump isn’t the first to make this shift, though he’s perhaps the most high-profile member of the GOP to do so and his comments have been greatly amplified in the saturated media environment surrounding the election. Running against incumbent Democratic Senator Harry Reid in 2010, challenger Sharron Angle consistently appealed to Second Amendment voters, with remarks like “I’m hoping we’re not getting to Second Amendment remedies. I hope the vote will be the cure for the Harry Reid problems.” At a 2012 NRA event, now-Senator Joni Ernst (IA) remarked, “I do believe in the right to carry, and I believe in the right to defend myself and my family — whether it’s from an intruder, or whether it’s from the government, should they decide that my rights are no longer important.” Rhetoric invoking “Second Amendment solutions” seems to be offered as a concrete Plan B for electoral politics: if you can’t get the votes, you can still get your guns.

The gender dynamics of the presidential contest also bear on how Trump’s comments are interpreted. Women in politics make highly visible targets for violence, as the assassination of Jo Cox and attempted assassination of Gabrielle Giffords suggest. It’s also evident from the growing threats of violence and death facing female political bloggers and their families. Threats of violence against women in the public sphere are intended to intimidate, silence and punish women who seek political power and influence. Worse yet, the dehumanizing rhetoric that accompanies these threats — e.g., Baldasaro’s comment that Clinton is a “piece of garbage” — works like a kind of accelerant to violence. Philip Zimbardo, the researcher behind the Stanford Prison Experiment and author of The Lucifer Effect, notes that dehumanization is a key psychological mechanism in promoting prejudice, aggression and violence.

Zimbardo writes that “Dehumanization occurs whenever some human beings consider other human beings to be excluded from the moral order” and, noting the role that political rhetoric plays in this process, argues that “dehumanizing agents suspend the morality that might typically govern reasoned actions toward their fellows (307).” Zibmardo’s experimental research reveals that simply applying dehumanizing labels toward individuals and groups of people — e.g., labeling them “an animalistic, rotten bunch” — promotes more aggressive and punitive behavior. His more applied research, which includes interviews with perpetrators of prisoner abuse at Abu Ghraib, makes a similar point — that dehumanizing rhetoric fuels a hostile imagination toward one’s enemy, lowering the moral and cultural barriers that normally mitigate abuse and aggression toward others and facilitating “destructive and abusive actions.”

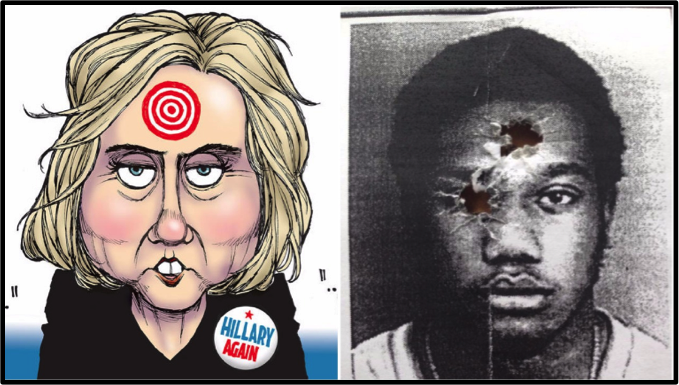

Here’s a powerful set of images to consider. In the image on the left, L.A. Times political cartoonist David Horsey suggests there is a target on Clinton’s head. The image on the right is a picture of a mug shot used for target practice by members of the North Miami Police Department. While the image on the left is stylized and could represent either a real or a figurative target, there’s less ambiguity in the image on the right. Black men are not just figurative targets of police violence. This pair of images is disorienting in the same way Trump’s Second Amendment comments are disorienting. There’s a dangerous possibility in the ambiguity. The metaphor breaks down when we consider the intimacy between the practice of violence and its reality. Taken together, the two images are discomforting because they point to the inherent danger in the GOP rhetoric surrounding Hillary Clinton and “Second Amendment solutions” more generally.

In this political climate, Trump’s comments are more than just poor sportsmanship or commonplace campaign metaphor; they are unethical. They offer an invitation to violence and a dog-whistle to homegrown terrorism. They are further indicative of misogyny, allegations of which have haunted Trump throughout his campaign. It’s important to recognize the real work that this kind of dehumanizing and violent rhetoric is doing and to pay attention to where metaphors grate uncomfortably against reality. Calls for Second Amendment solutions are an affront to our democratic principles and have the power to undermine our democratic institutions. Because of this, Trump’s aggressive rhetoric demands continued challenge and scrutiny, regardless of whether the campaign seeks to explain it away as jokes or sarcasm.

Erin C. Cassese is an associate professor of political science at West Virginia University. She earned a Ph.D. from Stony Brook University in 2007. Her research on gender and race in American politics has appeared in Legislative Studies Quarterly, The Journal of Politics, PS: Political Science & Policy, Politics & Gender, Sex Roles, and The Journal of Political Science Education.

Erin C. Cassese is an associate professor of political science at West Virginia University. She earned a Ph.D. from Stony Brook University in 2007. Her research on gender and race in American politics has appeared in Legislative Studies Quarterly, The Journal of Politics, PS: Political Science & Policy, Politics & Gender, Sex Roles, and The Journal of Political Science Education.