Tim Thornes was a linguistics graduate student at the University of Oregon when a chance project set the course of his studies for decades.

The Klamath Tribes in South Central Oregon were looking for someone to write a beginners phrase book for the Yahooskin dialect of Northern Paiute (Yahooskin is one of three groups comprising the Klamath Tribes). Thornes took the job. He partnered with tribal elder Irwin Weiser to write a book including greetings, the names of plants, animals, colors and more.

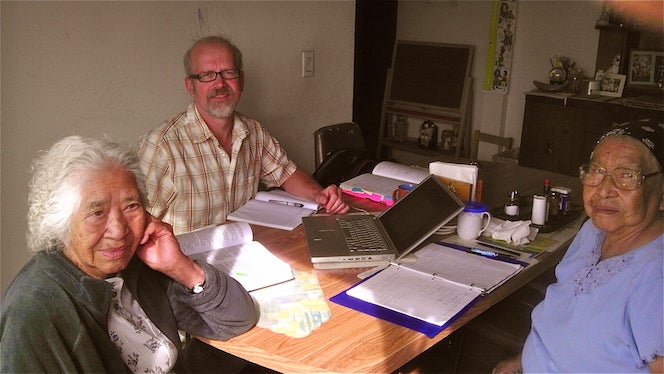

“I volunteered to do what I thought would be a great summer project. Twenty-five years later, here I am,” said Thornes, an associate professor of linguistics in Boise State’s Department of English, and one of just three American linguists who specialize in Northern Paiute.

He has co-edited a volume, Northern Paiute Texts Across Varieties, containing transcribed, translated and analyzed oral narratives in Northern Paiute. The volume is a supplement to the International Journal of American Linguistics (University of Chicago Press) as part of the journal’s Texts in the Indigenous Languages of the Americas series.

Connecting to history

Speakers of Northern Paiute are native to the high desert region that stretches from what is now South Central Idaho and Eastern Oregon across Northern Nevada and into Eastern California. Thornes and co-editor Maziar Toosarvandani from the University of California Santa Cruz included samples from nine distinct Northern Paiute communities in their volume. The samples include documentation from their own field work in those communities and materials that had been sitting on archive shelves – in some cases for more than a century – gathered by linguists and linguistic anthropologists in the past.

“When material is in an archive, it’s often not searchable,” said Thornes. “I want to do my part to make it easier for communities to connect to their own history as told by their elders.”

Thornes’ early collaborator, Irwin Weiser, died in the 1990s. But Thornes continued to work on language preservation with Weiser’s grandson, Steve Weiser. Weiser lives in Chiloquin, Oregon, and is a member of the Klamath Tribes. While Weiser is working to teach his native Yahooskin dialect to his 26 grandchildren and has led programs at local schools and community centers, he faces constant challenges, he said, including lack of money for such programs. The involvement of linguists like Thornes in language preservation and making materials more available is invaluable, he said. “People are looking for this.”

What’s in the volume?

The volume contains traditional stories, conversations and prayers. Some stories are autobiographical while revealing cultural details. Examples include interviews recorded by a Swedish folklorist in the 1950s with a speaker of the Bannock dialect about travel in the region. Another narrative is from a Bannock speaker who told the story of finding a nest of sparrow hawk chicks, trying to keep the growing birds as pets and eventually watching them fly away.

Each entry includes an English translation, a romanization (a term for the conversion of a language into Roman script) and lines of linguistic analysis.

Northern Paiute is among many indigenous languages considered endangered, said Thornes, with between 400 and 500 native speakers.

“Think about that in the context of a billion speakers of English, or half a billion speakers of Spanish in the world. To be able to fit all of the speakers of a language into one large room.”

Peace Corps and an introduction to linguistics

As a student, Thornes had not intended to focus on Northern Paiute. In his 20s, he worked as a Peace Corps volunteer in Gabon, in Central Africa. French was the official language. Thornes also encountered a variety of local languages spoken in the villages where he lived and worked. He met an anthropologist doing research in the area who introduced him to the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA), the standardized representation used by linguists of the sounds of spoken language. That was his first exposure to linguistics as an academic discipline.

“It planted a seed,” said Thornes.

Northern Paiute captivated him, including its unique word formation processes.

“Think of a verb that represents a change of a state of being, like cut, or open, or break,” said Thornes. “Break can mean a lot of things, breaking a window, breaking a sweat. It’s a different action.”

The way Northern Paiute makes the distinction is to have a generic verb root, and then to add a prefix that describes how, or with what instrument, one carries out the action. Creativity is inherent to Northern Paiute. Speakers are continually exchanging roots and prefixes to make new words.

“Take the verb ‘to open,'” said Thornes. “One prefix means to open something ‘with the fingers grasping.’ You’d use that for opening a doorknob.”

Other prefixes might indicate opening something by hitting it with your fist, or using the end of a long object, or pushing it with the flat of your hand.

“Everyone’s favorite is to use your hips or buttocks to do the action – like opening a door when you have a load of groceries in your arms,” said Thornes.

The intricacies of Northern Paiute, he said, are reminders “that nobody can really get to the bottom of a language… the language itself has always got another surprise.”

The study continues

Writing the first phrase book in Yahooskin led to more projects as Thornes entered his doctoral program. He began attending elders’ potlucks on the Burns Paiute Reservation in Eastern Oregon where, for the first time, he heard Northern Paiute spoken in social settings – including elders sharing stories with younger community members. Thornes got in the habit of taking notes and posting them as installments in the tribe’s weekly newspaper. Thornes helped form a group of speakers dedicated to documenting Northern Paiute and keeping the language alive. His ties to the Burns community grew.

Yolanda Manning, a Boise State alumna, is a native Northern Paiute speaker and a teacher in Owyhee, Nevada, on the Duck Valley Reservation. She met Thornes in 1989. They have worked on several projects since then, including creating Northern Paiute language materials in various media forms that teachers like Manning can use in their classrooms. Thornes helped Manning re-record and preserve an aging cassette tape of her grandmother speaking Northern Paiute. Manning has shared that recording widely with family and others.

“Tim’s work has been such an inspiration and an asset,” she said.

Thornes said he downplays his role as an expert or specialist and wants instead to shine light on “the grassroots work that is being done to restore indigenous languages to their rightful place in communities.”

“I feel very strongly that my relationships with the individuals I have worked with are the most important part of what I do, and I continue to learn from them, even from my friends who have passed on,” said Thornes.

His next project is a larger compilation of the Burns dialect of Northern Paiute – the dialect with the earliest documentation from the early 1900s.

Boise State linguistics alumni helped Thornes with his research for the Northern Paiute volume: Rylee Godfrey, Hannah Guzman, Emma Jones, Steena Trouten and Roxana Winston, who is continuing to work on the Burns project. Thornes received support for work on the recent volume from the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Osher Foundation.

Meet linguistics student Emma Halverson

One of Thornes’ hopes is that Boise State will continue to develop closer ties with area tribes. Student interest in studying indigenous languages is high, he said.

One current project is led by senior Emma Halverson, who’s majoring in linguistics with a minor in Latin. Halverson graduated from Renaissance High School in Meridian, Idaho and received the Capital Scholars Essay Scholarship and the Boise State Presidential Scholarship.

Halverson is working on an English translation of a grammar book, A Kootenai Grammar, written in the 1894 in Latin by a Jesuit priest at Montana’s St. Ignatius Mission near the Idaho border. She encountered the text when she was a student in Thornes’ class on native North American languages. Kootenai, also known as Kutenai and Ktunaxa, is a language native to what is now southeastern British Columbia, northwestern Montana and northern Idaho.

“Since I’m a linguistics major with a Latin minor, I thought that the grammar sounded fascinating and wanted to learn more about it,” said Halverson.

“I believe having this translation will be important because A Kootenai Grammar is a key part of the documentation of Ktunaxa, since it was the first grammar written about the language, but it’s largely inaccessible to English speakers,” said Halverson. “My goal is to use my studies in Latin translation and linguistics to create a new translation that renders the grammar available as an English resource and useful in a linguistic context.”

Explore linguistics at Boise State

– Story by Anna Webb