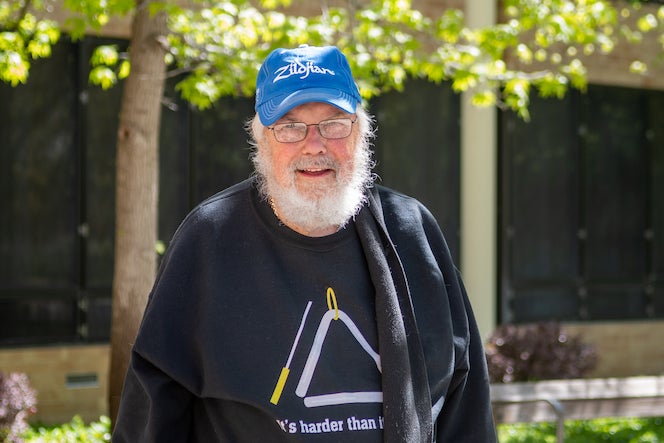

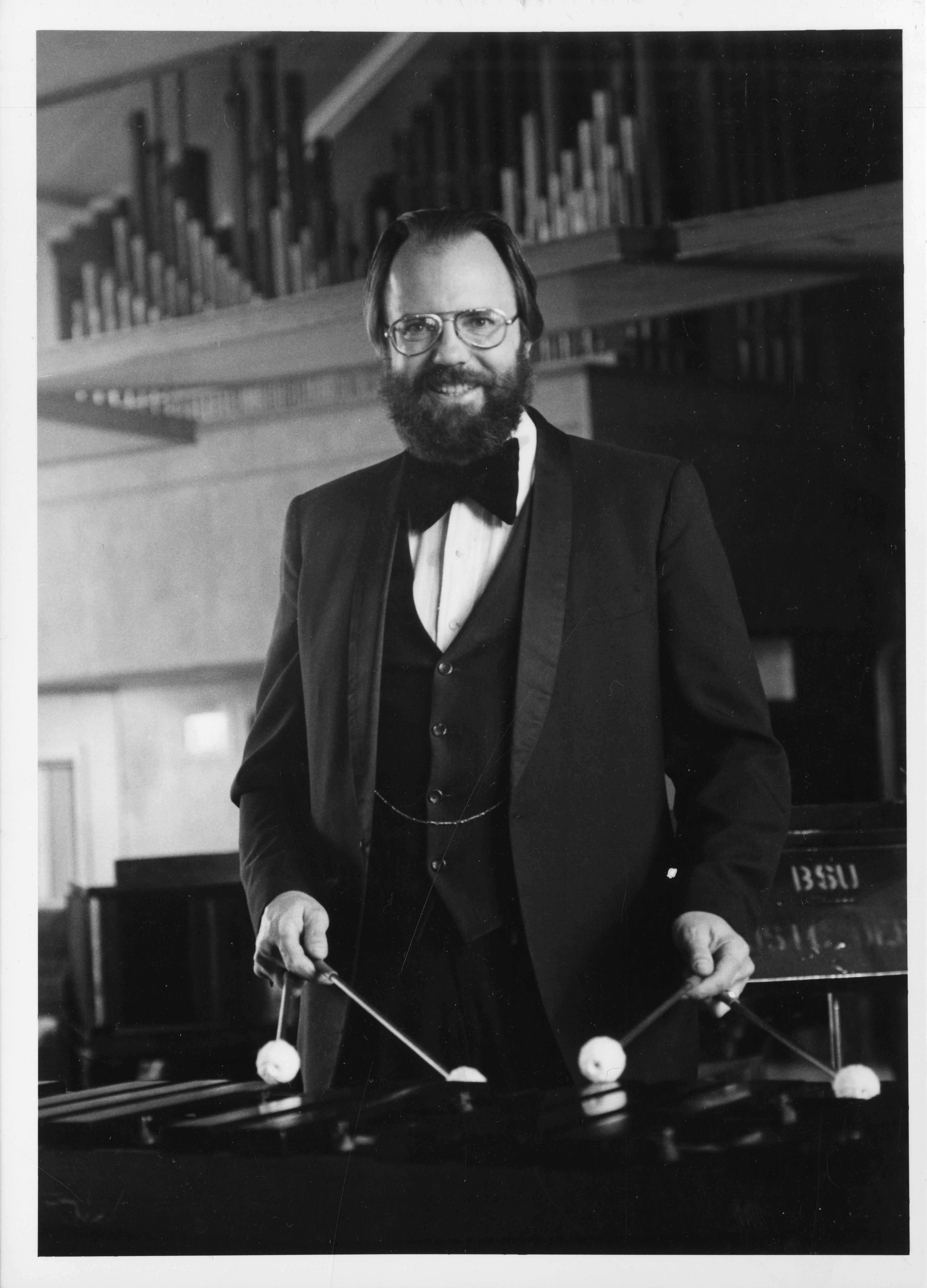

When the music department moved its offices into the newly built Morrison Center in the 1980s, professors got to choose whether they wanted an office with lots of space, or an office with a nice view. John Baldwin, a professor of percussion, founder and director of Boise State’s Percussion Ensemble, chose space to accommodate lots of instruments. At the moment, his office holds a marimba – his favorite instrument – and two snare drums. That’s a modest collection compared to what it’s held in the past. He’s been cleaning out.

In the spring of 2021, Baldwin retires from Boise State after 50 years of teaching. He will leave a legacy, including 27 file drawers of musical scores dating back to the late 1950s. He will take memories of colleagues and of the countless students who have pursued musical careers of their own. He’s been at the university long enough to see those successes, and, in some cases, to teach the children of his former students.

Kelley Smith teaches music and band at Chief Joseph School of the Arts in Meridian. She graduated from Boise State with a degree in music education. She studied with Baldwin and has remained a friend and colleague. Smith described Baldwin as a demanding professor, but one whose high standards are inspired by one thing: a desire for his students to do well. Smith noted Baldwin’s sense of humor – green and red leisure suits that made appearances at campus Christmas parties, but also his kind heart. Smith teaches at a school where a large number of students come from low-income homes. When Baldwin found out that many had unpaid lunch fees, he quietly paid them. Smith remembered playing in a concert with Baldwin shortly after the Oklahoma City bombing. Baldwin spontaneously dedicated the concert to the victims.

“Try playing without getting choked up after that,” Smith said.

Jim Jirak, an associate professor in the music department and artistic director of the Boise Philharmonic Master Chorale, agreed with Smith about Baldwin’s reputation for rigor in the classroom.

“Students would spend an entire semester learning one drum,” Jirak said. But, he added, the students trained by Baldwin – called upon to provide percussion for music ensembles across campus – are invariably well-prepared, on time, and serious about their art. Jirak praised Baldwin for teaching him valuable lessons about the nuances of tone in percussion, and for generously loaning instruments from his copious collection. Baldwin is a scholar, Jirak said, but he is also the kind of person who volunteers to cook burgers at department picnics and to weld his own trap tables to hold percussion instruments.

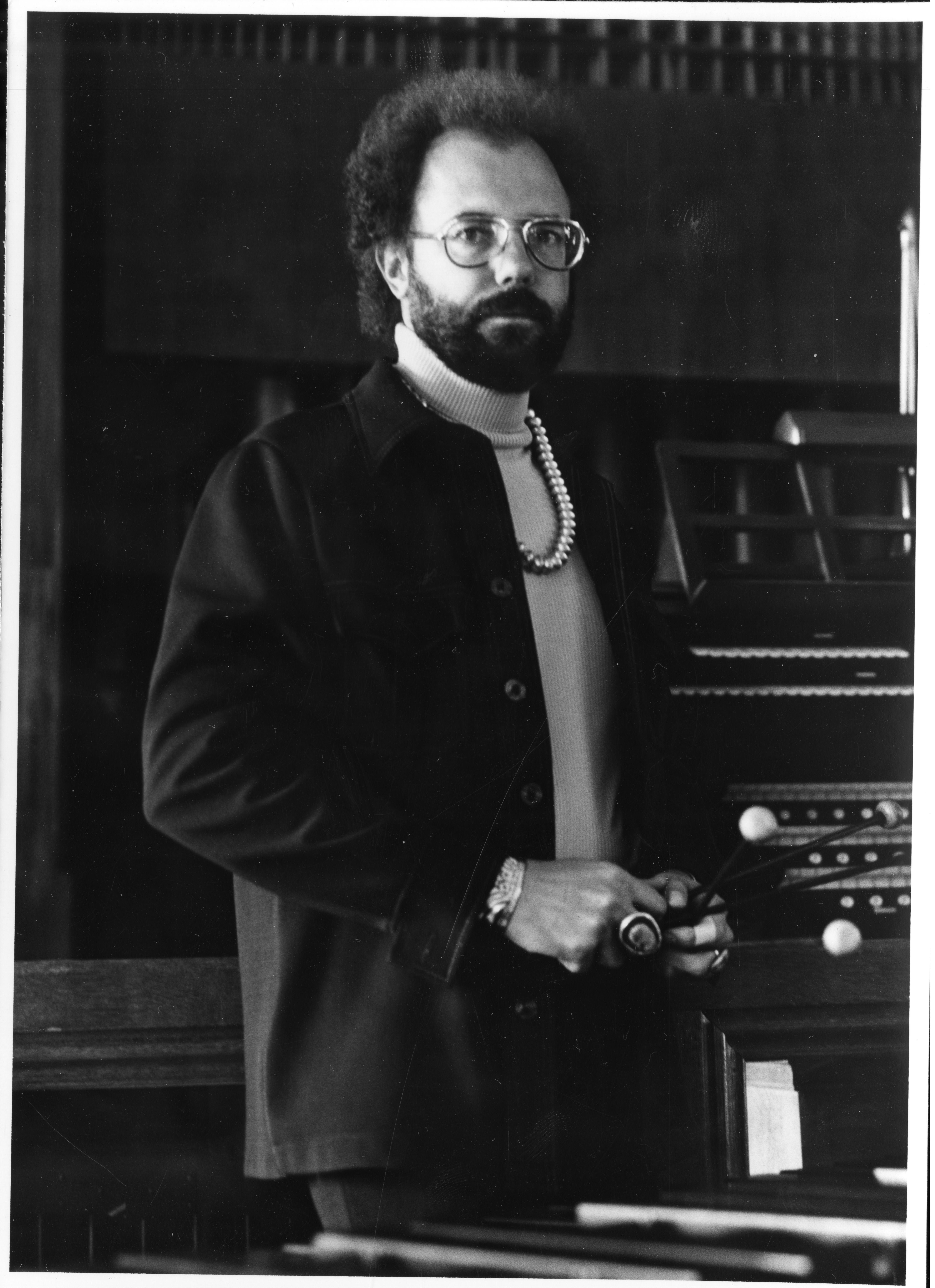

As much as a presence at Boise State, Baldwin has been a presence in the music community beyond campus. He has played percussion for the Boise Philharmonic for 50 years, primarily as principal percussion timpanist. Shortly after arriving in Boise in 1971, the century-old Boise Music Week program drafted him to direct “Man of La Mancha.” He’s worked on many Boise Music Week productions since, and recently became a life member of the organization. Thirty years ago, Baldwin and fellow professors from the region co-founded the Northwest Percussion Festival with the aim of giving classical percussion ensembles from the Northwest the chance to perform for one another and exchange ideas.

Baldwin counts co-founding the Verde Percussion Group with his fellow percussion players in the Boise Philharmonic in 1991 among his many career high points. The group plays percussion concerts for children, introducing young listeners to everything from bass drums to finger cymbals. The group, he estimated, has played for tens of thousands of students.

An early love of music

Baldwin, 81, grew up in Hutchinson, Kansas, as an only child, son of a pharmacist and a homemaker. He got his musical inclinations from his mother, he said. She studied dance in college and signed him up for piano lessons when he was in the fourth grade. He remembers his mom taking him to see a junior high band concert when he was in elementary school.

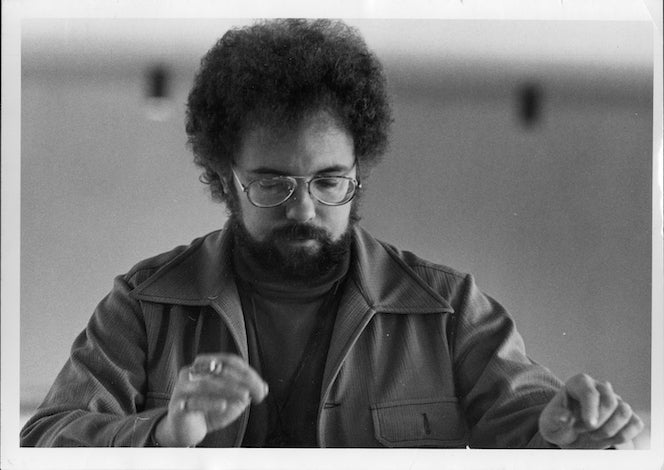

“There were two directors,” Baldwin said. “When one directed, the other played percussion because there weren’t enough percussion players.” Baldwin realized that was a need he could fill. He continued to play the piano, but began also studying percussion. He played in junior high band and orchestra, and, in junior high, was a charter member of the Hutchinson Skyryders, a drum and bugle corps sponsored by the American Legion that lived on until just 15 years ago. At Wichita State, where Baldwin received his undergraduate and master’s degrees, he distinguished himself by performing a double recital in piano and percussion for his undergraduate music education degree. Another honor came when, after finishing his master’s, he attended the Aspen Music Festival in Colorado. Celebrated percussionist and professor George Gaber invited Baldwin to perform Bartok’s Sonata for Two Pianos and Percussion – the first time a student had ever been invited to play in the faculty recital.

The move west

Baldwin finished his doctorate at Michigan State University and taught at Wisconsin State University – Oshkosh. When the midwestern winters became too much, Baldwin and his wife, Alison Baldwin, a violinist and teacher, started looking for new possibilities. Baldwin sent letters to several colleges and universities, and Boise State responded. It happened that Mel Shelton, a fellow Kansan, was a professor at Boise State at the time. He’d known of Baldwin’s work in his high school drum corps. Baldwin got the job.

“We packed up two kids, two dogs in a U-Haul,” Baldwin said. They bought a model home in a then-new subdivision where they still live today.

The Baldwins have two daughters, Shannon and Shawn, nine grandchildren, one great-granddaughter, and one step-great-grandson.

What’s next?

The pandemic gave Baldwin a glimpse of what retired life will be like, he said. He has an acre of land to take care of at home in Boise, and plans to spend time at his family’s homes in Donnelly, Idaho and in Colorado. He will retire from playing in the Boise Philharmonic, but will remain on the group’s substitution list, and plans to continue playing in other venues.

He’ll miss Boise State, he said, “mainly the kids, but also the family orientation of the faculty. We’ve had a few loners, but mostly, have worked together.”

He recognizes the daunting task any new professor, of stepping into a position held by one person for five decades. “I will do what I can to help them,” Baldwin said, “I don’t want to step on any toes, but I want to make the transition as seamless as possible.”