“Research” doesn’t just mean generating new discoveries through experimentation. Boise State supports Boyer’s model of scholarship, which expands the definition of research and creative activity to include applying and integrating knowledge into other settings, as well as teaching it.

From working in the Simulation Center to partnering on faculty projects, discover the kinds of path-breaking scholarship that undergraduate research assistants work on the School of Nursing.

Application in the Simulation Center

The College of Health Sciences Simulation Center is accredited in both teaching and research. So it’s no shock that undergraduate research assistants (URAs) in the Simulation Center practice many different types of scholarship: application, as they take existing theory and knowledge and apply it to new simulation scenarios; teaching, as these scenarios are developed and embedded into the curriculum; and discovery, as they conduct studies to measure the educational effectiveness of their scenarios.

Initially when junior Grace Ellison signed up to be a research assistant, she thought her work would be “all numbers and doing studies”, she said.

But she’s discovered Simulation Center research is more “taking things that have been found and applying it into education, and then testing how well what we came up with works for educating people,” Ellison said. “I obviously participate in sims, being in the program, so being on the other side of it has been not what I expected. Knowing all the behind-the-scenes stuff is pretty cool.”

Ellison works under Tracee Chapman, clinical assistant professor and Interim Director of Simulation-based Education and Research, with two other URAs, Isabel McGregor and Hannya Ornelas.

Ellison and Ornelas have been able to be a part of the patient voice project, an interview process that increases realism in simulations by basing scenarios on actual patient experiences. Before being a URA, Ellison didn’t know this was part of the scenario-writing process.

“I feel like I have a greater appreciation for the sims now,” she said. “Now I cherish it more, I guess, because I know how much work has gone into it.”

Chapman and her team are developing a scenario for students to practice working with a family whose child has Down Syndrome. Ellison and Ornelas developed a question guide that Chapman used to interview families about their experiences.

“The RAs bring so much energy, excitement and passion for improving the students’ understanding of important nursing concepts through simulation,” Chapman said. “Their dedication to implementation science is critical for improving their future patient interactions and outcomes.”

Learning decay and the scholarship of teaching

Ellison and McGregor are investigating the learning decay of nursing students when it comes to content about sepsis. Learning decay refers to students’ rate of retaining knowledge; that is, how long do you remember what you’ve been taught?

“We’re actually looking at the cohort I’m in, and then we’re going to follow us for the next two semesters to see what our learning decay was,” McGregor explained.

Under Chapman’s supervision, the team will survey McGregor’s cohort to track gaps in their understanding of sepsis. The team aims to prevent learning decay in future cohorts by adjusting future sepsis curriculum based on data from the cohort.

“Obviously, I can’t participate in the study since I’m researching my own cohort, but it is cool because I feel like I know all the behind-the-scenes,” McGregor said. “I’m excited because it will benefit future cohorts…Boise State, and the nursing program specifically, is always trying to improve itself, which is great to benefit our learning.”

While their scholarship with the Simulation Center has been nontraditional, McGregor has experienced “so many benefits”, and Ellison said it has been “a great experience.”

“All research impacts people in some way, but I like that I can see the direct impact, knowing we’re developing sims for my program that I may see in the future or people I may know might go through,” Ellison said.

Interdisciplinary discoveries

In addition to scholarship in the Simulation Center, Hannya Ornelas also works with assistant professor Kate Doyon. Their interdisciplinary team is working to improve hospice and palliative care for refugees.

“It’s super cool to be part of this team because I went to Borah High School,” Ornelas said. “I went to school with a lot of refugee students, which is great to see this different perspective of hospice and palliative care in the refugee community.”

Clinicians and refugees often do not share common cultures, languages or communication norms, so Doyon has been building a community advisory board to create a communication guide. They’re working with stakeholders–including refugees and providers–to develop prompts that will enhance the care refugees receive, starting on the level of communication.

Ornelas said the refugees they interviewed “gave us a lot of insight on different cultures and how we can go about and make prompts.”

The prompts are short phrases to remind the healthcare team of best ways to interact with refugees and productively approach conversations.

They emphasize the patients’ autonomy and individuality; just as the provider is the expert in health information, Ornelas explained that the prompts encourage the care team to recognize the “patients as experts” of their own experiences.

Ornelas has seen the need for this in her own work as a certified nursing assistant (CNA) in an intensive care unit. “When asking certain questions, doctors may be very blunt or not ask them respectfully,” Ornelas said. “That throws off the whole conversation…I’ve definitely seen that happen.”

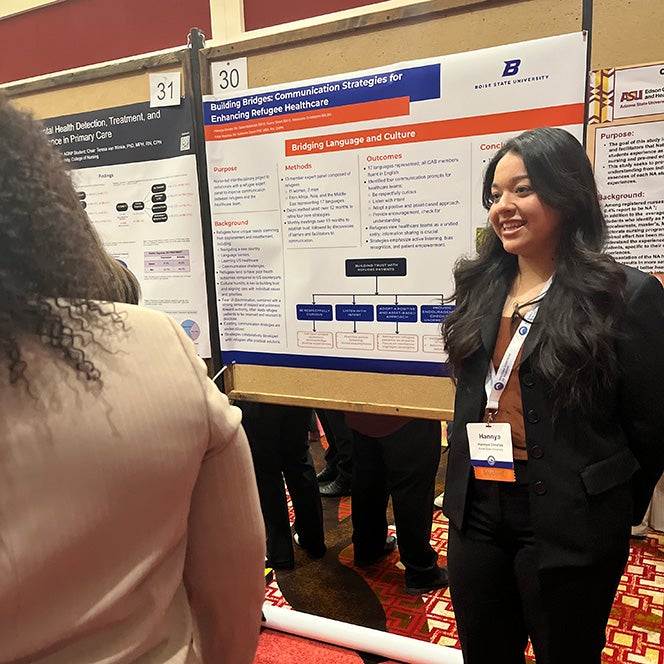

Earlier in April, Ornelas presented this work at the Western Institute of Nursing annual conference in Spokane, WA. Her poster outlined the conversation prompts and how they can be used in real-world situations, taking their scholarship the gamut of discovery, integration and application.

“Everybody part of the healthcare team is able to use these prompts to provide care,” Ornelas said, from the physicians and nurses to the front desk workers as patients sign in to facilities.

Embracing hospice and palliative care

Palliative and hospice nursing are associated with end-of-life care. When Ornelas first signed up to be a research assistant and heard about projects in these areas, she was “kind of taken aback,” Ornelas said. “I was like, ‘That seems a little depressing.’”

But she soon found it captivating.

Ornelas is also enrolled in an Honors College course on the meaning of life and death, and she’s seen many relevant overlaps in the content she’s learning. She brings knowledge she gained from being a URA into “great discussions” in class, she said.

“I feel like this research has taken me in,” Ornelas said. “I was very hesitant at first to even talk about palliative and hospice care, but I think being able to do this has not only made me a better student, but also changed my perspective.”

Ornelas has a deeper sense of empathy when she encounters patients and their families in clinical settings. “That class and this research has really prepared me to be able to be in those shoes,” she said. “I feel better about navigating that entire process, when I do become a nurse.”

Genomics and teaching

Junior Cora Serafine is researching topics in genomics under the supervision of associate professor Molly Prengaman. While she isn’t in front of a classroom or instructing students at the bedside, she’s practicing the scholarship of teaching by helping develop curriculum.

Genomics is a relatively new field within healthcare, developing in the 20th century as DNA sequencing and genome mapping advanced. Serafine has been researching background literature about how providers can include genomics in their plans for patient care.

She and Prengaman are interested in promoting basic knowledge about genomics to be able to encourage that type of care within their scope of practice.

“Different screenings related to genes can be valuable knowledge for nurses, especially advanced practice nurses like nurse practitioners,” Serafine said. “There’s so much to be said for having more knowledge about your genes and what you’re predisposed to, just the preventative medicine that can provide…It could allow you to make lifestyle or health modifications that could make you less likely to have other health issues later down the line.”

Nurses are often more engaged with the preventative side of healthcare – encouraging healthy habits that prevent problems from arising – while doctors are trained to address existing problems.

Serafine works as a medical assistant in a family medicine practice in Meridian, Idaho, and patients at her workplace are often afraid to get genetically tested for conditions if their doctor suggests they might be predisposed to it. While Serafine understands most people’s hesitation, she also sees it as an opportunity for nurses to advocate for patients’ health.

She wonders if more patients would be inclined to get tested “if nurses, people who are more on the patient level, rather than a “big bad scary doctor”, tell you something like that,” she said.

Prengaman hopes to weave the research about genomics that they’ve gathered into relevant courses throughout the graduate program–like those that cover chronic illnesses or healthy aging–not just introduce an entirely new class.

“Learning about the nurse’s role in promoting different avenues of care” has been a highlight of Serafine’s work so far, she said. “You don’t think about that a lot when you’re in nursing school. It’s always like, ‘Okay, do X, Y, and Z, but then like…call a doctor.’ So it’s been really cool to see how nurses do play a big role in that.”

Serafine’s interest in genomics has grown because of her work as a URA. She hopes to keep incorporating genomics into her studies “because so far it’s shown me how just having that knowledge can change the trajectory of your life,” she said. “It’s really impactful.”

What is it like as a nursing RA?