Sara Rostron is a native Idahoan. She is graduating with a major in psychology and minor in biology which combined her interest in using biological structure and function as a basis to understand mental processes. Some of her favorite topics include how personality traits shape interpersonal relationships, gender and sexuality, and how to improve the lives of those impacted by mental illness. Sara intends on going to graduate school next year. In her free time, she enjoys doing artwork and expanding her garden.

Abstract

Bipolar Disorder (BD) is a mental disorder with mood fluctuation and irritability. Irritability is established as a poor predictor for mental health and has been linked to more BD symptoms. Risk factors of higher irritability may involve the inability to cope with feelings. This study hypothesized repressive coping increases irritability, and that there is a relationship between repressive coping and alexithymia. Ninety participants were selected for the correlational design. A significant positive relationship was found between repressive coping and higher irritability, as well as alexithymia and higher irritability, but no significant difference between repressive coping and alexithymia. It appears that repression and alexithymia increase irritability, but alexithymia is present in most people with BD regardless of their coping style.

Repressive Coping and Irritability Incidence in Bipolar Disorder

Bipolar Disorder (BD) is an illness that involves a manic (BD type I) or hypomanic (BD type II) phase and a depressive phase. It impacts between 4% and 5% of men and women worldwide (Wu et al., 2017) with the highest incidence in the United States (Merikangas et al., 2011). Roughly half of those cases are split between BD-I and BD-II. BD is most likely due to heritability, but the exact mechanism has not been discovered as there are no identified markers or genes yet (Wu et al., 2017). Existing research contains an understanding of what (hypo)mania symptoms are, how both (hypo)mania and depression may be evaluated and diagnosed, factors that may contribute to BD onset, such as environment (Corry et al., 2017), and how common the presence of other comorbid disorders, like anxiety, are (Aas et al., 2016).

Since BD involves significant mood shifts, a common theme in BD research evaluates mood disturbance. This indicator is commonly represented by irritability. This is likely chosen because there appears to be an association between experiencing irritability and experiencing more severe BD symptoms and higher suicidality (Berk et al., 2017). Preliminary understanding on irritability and its relation to symptom experience has been important in determining how the variable impacts a BD patient long term. One study evaluating incidence of BD patients with anxiety found that irritability was associated with both anxiety and agitation (Serafini et al., 2018). The same researchers found that the depressive phase shows more signs of irritability than in the mania phase, though irritability is still possible in (hypo)mania (Berk et al., 2017).

In addition to irritability, BD patients may have a more difficult time in coping with their emotions. Difficulty in verbalizing or externalizing thoughts and emotions is defined as alexithymia, another common topic in BD research. Alexithymia levels are associated in bipolar patients more than a control (Karayagiz & Basturk, 2016). Alexithymia levels are quite high especially in patients with depression; though therapy may be helpful, the level tends to stay higher versus a control, indicating that alexithymia could be considered a personality trait due to its stability (Karayagiz & Basturk, 2016). A longitudinal study confirmed there is an association between the presence of alexithymia and depression, which suggests it may be an important predictor in future studies to evaluate morbidity (Serafini et al., 2016).

Another way in which BD patients may have a disadvantage is in coping. Coping is an important skill in life as it dictates how one responds to life events, whether the events are positive or negative. How one responds to stressors can have a profound impact on overall mental health. BD patients not only have to cope with severe symptoms but suffer from higher frequency and intensity of symptoms if they do not acknowledge them (Apaydin & Atagun, 2018). The known maladaptive types of coping mechanisms, or negative coping skills, evident in BD patients are “…rumination, catastrophism, self-blame, substance use, risk-taking, behavioral disengagement, problem-direct coping, venting of emotions, or mental disengagement” (Apaydin & Atagun, 2018). BD patients are already predisposed to more severe feelings associated with events that are linked to either reward or perceived failure and are more likely to catastrophize events (Chan & Tse, 2018). This inclination may trigger increased emotionality and decreased feelings of control negatively impacting their ability to cope with life experiences.

Negative coping is linked to depression. The use of negative coping skills is associated more in BD patients than those without BD (Apaydin & Atagun, 2018). Implementing methods of how to practice adaptive coping skills could improve onset of the disease, symptom severity, enhance environmental support, and decrease hospitalization. Using positive coping mechanisms has been linked to better mood in those with BD (Chan & Tse, 2018), thus reinforcing that a negative coping style, such as repression, could be expected to show more severe symptoms of illness and poorer mood overall.

Limitations in these BD studies involve low sample size numbers, primarily self-report measurements, specific interpretations of coping skills undifferentiated between BD types I and II, demographic used, and few longitudinal studies. Additionally, it appears that current studies have not specified all types of maladaptive coping, specifically a category which could be a marker for alexithymia and irritability: repressive coping. This is a coping mechanism in which people deny feelings or emotions, and ignore stressful thoughts (Singer, 1990). Though not discussed yet in literature, alexithymia is similar in nature to repressive coping. Since BD patients are associated with higher alexithymia levels (Karayagiz & Basturk, 2016), repressive coping may be an important link in identifying maladaptive coping.

Research has clearly indicated that irritability is associated with poorer mental health, especially in BD patients who already experience amplified emotionality. What is not understood, however, is if certain coping mechanisms are associated with an increase in irritability. Given the association between BD patients and their propensity in having a harder time verbalizing and using positive coping skills, as well as a predisposal to negative emotions, repressive coping needs evaluation.

Proposed Methods

Research is necessary to understand if there is a relationship between repressive coping and incidence of irritability in those with bipolar disorder. It is already understood that irritability is highly correlated to problems within psychological disorders. Our hypothesis is that repressive coping causes an increase in irritability in people with BD types I and II and that alexithymia causes an increase in irritability. Additionally, default coping type may be an indicator for alexithymia. We hypothesize repressive coping causes an increase in alexithymia.

Participants

Ninety participants chosen randomly by mail will be selected after completing the Mood Disorder Questionnaire (MDQ) which scores for presence of bipolar spectrum disorder (Hirschfeld et al., 2000). These preliminary questionnaires will be scored by the researchers to determine presence of moderate to severe bipolar disorder (type I or II), and participant stability (must be outpatient only). Forty-five women and forty-five men will be selected between the ages of 18 and 45. Reimbursement includes a free counseling session upon completion of the study.

Design

This study will be correlational. Variables will include irritability level, repressive coping, and alexithymia level. All variables are continuous and are graded on a numeric scale. For irritability and alexithymia, levels are graded as: 1-3 low, 3-5 moderate, 6-9 high. For coping style, 1-3 indicates repressive coping is used occasionally and 4-8 indicates repressive coping is the participant’s primary coping style.

Procedure

This procedure will involve three self-report questionnaires that participants will fill out individually at home. The Brief Irritability Test (BITe) will be used to score irritability as low, moderate, or high (Holtzman, O’Connor, Barata, & Stewart, 2015). The Psychological Inventory-Alexithymia Scale (PTI-AS) will be used to score alexithymia tendencies as low, moderate, or high (Gori, Giannini, Palmieri, Salvini, & Schuldberg, 2012). The Coping Orientation to Problems Experienced Inventory (COPE-48) will be used to score coping style, differentiated by tendency to use repressive coping only sometimes or most of the time (Ortega, Freixanet, & Deu, 2016).

Analyses

A correlational analysis will be used. Irritability will be plotted as a function of repressive coping, irritability will be plotted as a function of alexithymia, and alexithymia will be plotted as a function of repressive coping. To determine statistical significance, alpha will be used at 0.05.

Proposed Results

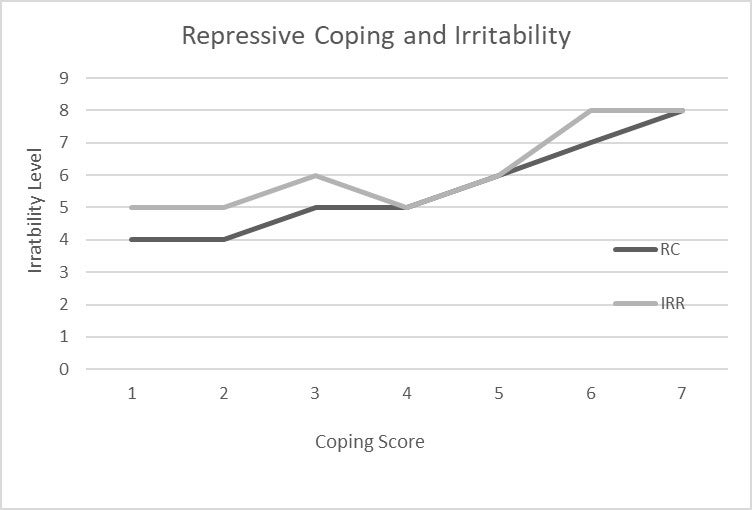

COPE survey scores for coping style related to participants’ BITe survey scores for irritability indicated that the regular use of repressive coping skills is positively associated with irritability levels. Those who had less tendency toward repressive coping scored lower in irritability. The result was statistically significant (Figure 1A).

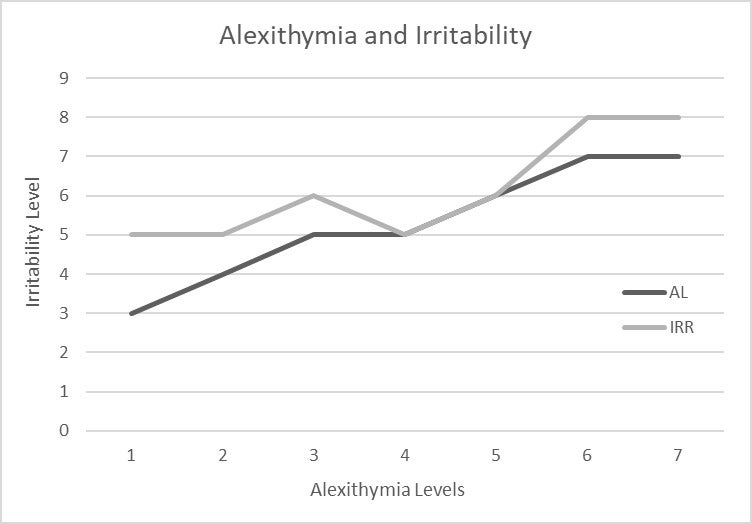

PTI-AS survey scores related to BITe survey scores indicated that alexithymia scores are positively associated with irritability scores. Those with lower baseline alexithymia scores had moderate irritability, but higher alexithymia also showed higher irritability. This result was statistically significant (Figure 1B).

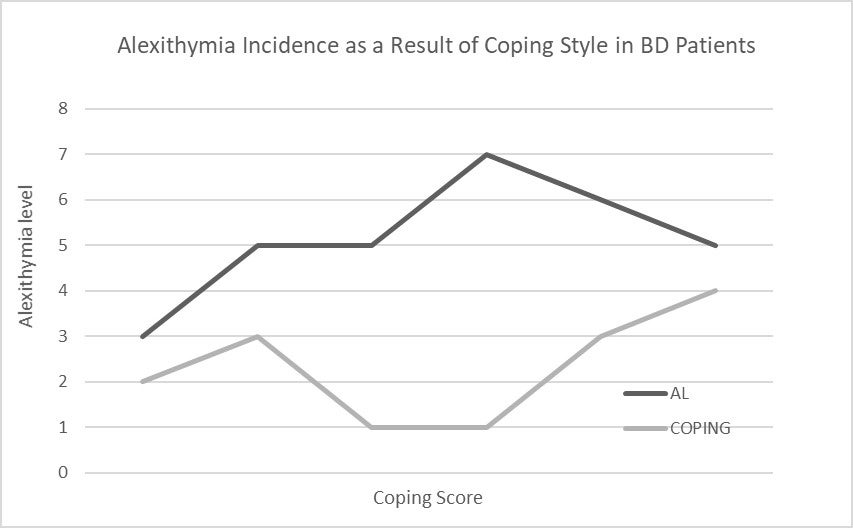

COPE survey scores related to PTI-AS survey scores indicated that there is no statistically significant relationship between repressive coping and alexithymia. Repressive coping was not a reliable variable in predicting alexithymia score.

Discussion

Irritability is associated with problematic thoughts and feelings and is a prominent symptom present in those with BD, though certain traits and behaviors must be explored to find if they increase irritability even further. Targeting the source of mood fluctuations will be important in improving quality of life in BD patients.

I hypothesized that repressive coping causes an increase in irritability in people with BD. My proposed results indicated that there was a significant positive correlation between those who scored high in repressive coping (high= primary coping style) and high in levels of irritability. There was also a significant positive correlation between high alexithymia levels and high irritability. There seems to be an association between repressing thoughts, as well as having difficulty in describing thoughts and feelings, in increasing irritability. There was no correlation between repressive coping and alexithymia, however. This could be due to the fact that regardless of coping style, BD patients have higher alexithymia levels versus a control (Karayagiz & Basturk, 2016).

Further direction for this research should include differentiating bipolarity into two levels (BD types I and II), the use of more than self-report questionnaires, and longitudinal studies. The current proposed results support previous research that showed damaging effects of maladaptive coping (Apaydin & Atagun, 2018), that alexithymia is a stable trait (Karayagiz & Basturk, 2016), and show preliminary association between repressive coping and irritability. This new relation could help psychiatric professionals add supplemental treatment, such as coaching patients toward positive coping skills to improve BD symptoms.

BD is most prevalent in the United States and there is notable risk of suicide ideation and/or attempt. Research of risk factors, such as irritability, will be crucial to continue to improve the longevity of BD patients.

References

Aas, M., Henry, C., Andreassen, O. A., Belliver, F., Melle, I., & Etain, B. (2016). The role of childhood trauma in bipolar disorders. International Journal of Bipolar Disorders, 4, 1–10. doi: 10.1186/s40345-015-0042-0

Apaydin, Z. K., & Atagun, M. I. (2018). Relationship of functionality with impulsivity and coping strategies in bipolar disorder. The Journal of Psychiatry and Neurological Sciences, 31, 21–29. doi: 10.5350/DAJPN2018310102

Berk, L., Hallam, K. T., Venugopal, K., Lewis, A. J., Austin, D. W., Kulkarni, J., … Berk, M. (2017). Impact of irritability: A 2-year observational study of outpatients with bipolar I or schizoaffective disorder. Bipolar Disorders, 19, 184–197. doi: 10.1111/bdi.12486

Chan, H. W. S., & Tse, S. (2018). Coping with amplified emotionality among people with bipolar disorder: A longitudinal study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 239, 303–312. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.07.025

Corry, J., Green, M., Roberts, G., Fullerton, J. M., Schofield, P. R., & Mitchell, P. B. (2017). Does perfectionism in bipolar disorder pedigrees mediate associations between anxiety/stress and mood symptoms? International Journal of Bipolar Disorders, 5, 1–11. doi: 10.1186/s40345-017-0102-8

Gori, A., Giannini, M., Palmieri, G., Salvini, R. & Schuldberg, D. (2012). Assessment of alexithymia: Psychometric properties of the psychological treatment inventory-alexithymia scale (PTI-AS). Psychology, 3, 231–236. doi: 10.4236/psych.2012.33032

Hirschfeld, R., Williams, J.B.W., Spitzer, R. L., Calabrese, J. R., Flynn, L., Keck, P. E.,… Zajecka, J. (2000). Development and validation of a screening instrument for bipolar spectrum disorder: The mood disorder questionnaire. American Journal of Psychiatry, 157, 1873–1875. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.11.1873

Holtzman, S., O’Connor, B.P., Barata, P.C., and Stewart, D.E. (2015). The brief irritability test (BITe): A measure of irritability for use among men and women. Assessment, 22, 101–115. doi: 10.1177/1073191114533814

Karayagiz, S., & Basturk, M. (2016). Alexithymia levels in patients with unipolar and bipolar depression and the effect of alexithymia on both severity of depression symptoms and quality of life. Anatolian Journal of Psychiatry, 72, 362–368. doi: 10.5455/apd.215633

Merikangas, K. R., Jin, R., He, J., Kessler, R. C., Lee, S., Sampson, N. A., …Zarcov, Z. (2011). Prevalence and correlates of bipolar spectrum disorder in the world mental health survey initiative. Archives of General Psychology. 68(3), 241–251. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.12

Ortega, M. Y., Freixanet, G. I. M., & Deu, F. (2016). The COPE-48: An adaptad version of the COPE inventory for use in clinical settings. Psychiatric Research, 246, 808–814. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.10.031

Serafini, G., Gonda, X., Pompili, M., Rihmer, Z., Amore, M., & Engel-Yeger, B. (2016). The relationship between sensory processing patterns, alexithymia, traumatic childhood experiences, and quality of life among patients with unipolar and bipolar disorders. Child Abuse and Neglect, 62, 39–50. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2016.09.013

Serafini, G., Geoffroy, P. A., Adavastro, G., Canepa, G., Pompili, M., & Amore, M. (2018). Irritable temperament and lifetime psychotic symptoms are predictors of anxiety symptoms in bipolar disorder. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 72, 63–71. doi: 10.1080/08039488.2017.1385851

Singer, J. (1995). Beyond Repression and the Defenses. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 479.

Wu, M., Mwangi, B., Cavalcante-Passos, I., Bauer, I. E., Cao, B., Frazier, T. W.,… Soares, J.C. (2017). Prediction of vulnerability to bipolar disorder using multivariate neurocognitive patterns: a pilot study. International Journal of Bipolar Disorders, 5, 1–7. doi: 10.1186/s40345-017-0101-9