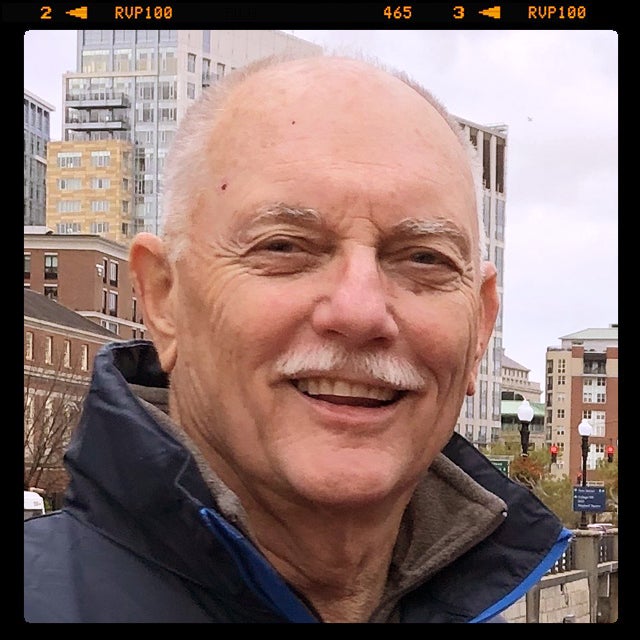

In our “Five Questions” feature we ask scholars, activists, and public officials five short questions about their work (and other things). Here, Gary Moncrief, retired Professor of Political Science at Boise State University, addresses a key issue being taken up by the Idaho Legislature in the 2020 session: redistricting.

WE HEAR REDISTRICTING IS AN ISSUE IN IDAHO’S LEGISLATIVE SESSION THIS THIS YEAR? HOW COME?

There are a couple of reasons. First, reapportionment and redistricting occur every ten years, after the decennial census count is conducted, and we get updated population figures for the state, counties, cities and neighborhood areas (precincts). The census count begins in March of this year, and the new census figures should be released to the state by March of next year. At that point, the state must draw new legislative district lines to reflect population changes.

Second, the changes being discussed would require an amendment to the state constitution. Any changes to the state constitution about how we do redistricting would have to be made this year, since they would require a vote by the citizens in a general election, and the general election is this November.

There are two separate issues being discussed by legislators, and they have very different implications. One is to change the make-up of the redistricting commission itself, and this proposal is quite clearly an effort to shift control from a bipartisan system to one controlled by the majority party. In my opinion, this change would make partisan gerrymandering more likely in Idaho.

The other issue concerns the number of districts. Currently, the Idaho Constitution mandates that we have between 30 and 35 legislative districts. But it also mandates that any valid redistricting plan should not create legislative districts that merge parts of one county with another county unless absolutely necessary. This provision, along with the fact that Idaho is an oddly shaped state with a great deal of sparsely populated land, means that some of the rural districts are very large in terms of square miles.

Some legislators think we could ease this situation by increasing the number of legislative districts to as many as forty. They believe that this would make it easier to create districts that would be a bit smaller and comply with the stipulation that counties not be “cut” more than necessary. Fundamentally, this issue is not a partisan one, in that it does not attempt to give more power over the process to one party.

These issues are very different in terms of how they will be approached. The first is driven by partisanship and the question of whether bipartisanship is more appropriate than partisan gerrymandering. The second is driven by a concern for rural representation and the need to cut fewer county boundary lines. It is possible it could have partisan consequences also, but basically it is not about seeking a partisan advantage. The first issue, however, is clearly about seeking a partisan advantage.

I anticipate that both these issues will be set forth by the legislature this year as separate constitutional amendments. In order to qualify for the November 2020 ballot, they need to pass the legislature with at least a two-thirds majority in each chamber.

HOW DOES IDAHO HANDLE DECISIONS ABOUT REDISTRICTING?

“Redistricting” means redrawing the actual boundary lines for the electoral districts in the state. The lines have to be redrawn so that there are basically the same number of people in each state legislative district. This is also true of other types of electoral districts for local governments, like city council districts or school board districts. Redistricting is important because the way the district lines are drawn can definitely affect who wins and who loses the election in that district.

In 1994, the citizens of Idaho passed a constitutional amendment to change the way redistricting was done in the state. The amendment created an independent commission consisting of three individuals chosen by Republican party leaders and three chosen by Democratic party leaders. At least four members must approve a plan, which means there must be some bipartisan support for a plan to be approved. Sixty-four percent of the voters approved this constitutional amendment.

In 2018 the Idaho Republican Party adopted a party platform that included a proposed change in the way the Independent Redistricting Commission is formed. The proposal is to have a seventh member added to the Commission. That member would be chosen by three statewide elected officials, all of whom are currently Republicans. In other words, this proposal would create a commission with a majority of members chosen by Republicans.

Some Republicans are quite clear about the intent of this proposal, arguing that since the Republicans are the majority party, “it would only be fair to allow the districts to be drawn with Republican control.”1

Today, at least fourteen states have independent redistricting commissions, and almost all of them are bipartisan or non-partisan. In fact, the trend in the past decade is to create independent commissions with a mix of Republicans, Democrats and Unaffiliated Voters. You can see the various commission arrangements here.

There are at least four more states considering independent bi-partisan or non-partisan commissions this year. To my knowledge, no state with such a commission has ever reverted to a partisan system, although there was an effort by the majority Democrats in New Jersey to change the system two years ago. The public reaction was swift and substantial, and the Democrats eventually withdrew the proposal.

IDAHO HAS BEEN GROWING FAST. HOW IS THAT CONNECTED TO REDISTRICTING?

Idaho has indeed been growing fast, but not in a random way. Almost all of the growth in the past decade is in urban areas. Three counties—Ada, Canyon and Kootenai—account for well over half of all the growth in Idaho. There is also some growth in a few counties such as Twin Falls and Bonneville, but many rural counties are actually losing population.

Since legislative districts must be redrawn after every census to reflect these population shifts, urban/suburban areas will gain some districts at the expense of rural areas. Some of these shifts will be substantial. For example, there are currently 35 state legislative districts in Idaho, and after the last redistricting in 2012, they ranged in population between 42, 610 and 46,955. The average was about 45,000.

Due the uneven population growth since 2012, the range in district population today is roughly 44,000 to 70,000. Obviously, substantial changes are necessary to bring districts back into “one person, one vote” compliance.

GERRYMANDERING HAS BEEN IN THE NEWS A LOT LATELY. IS THAT OF CONCERN HERE?

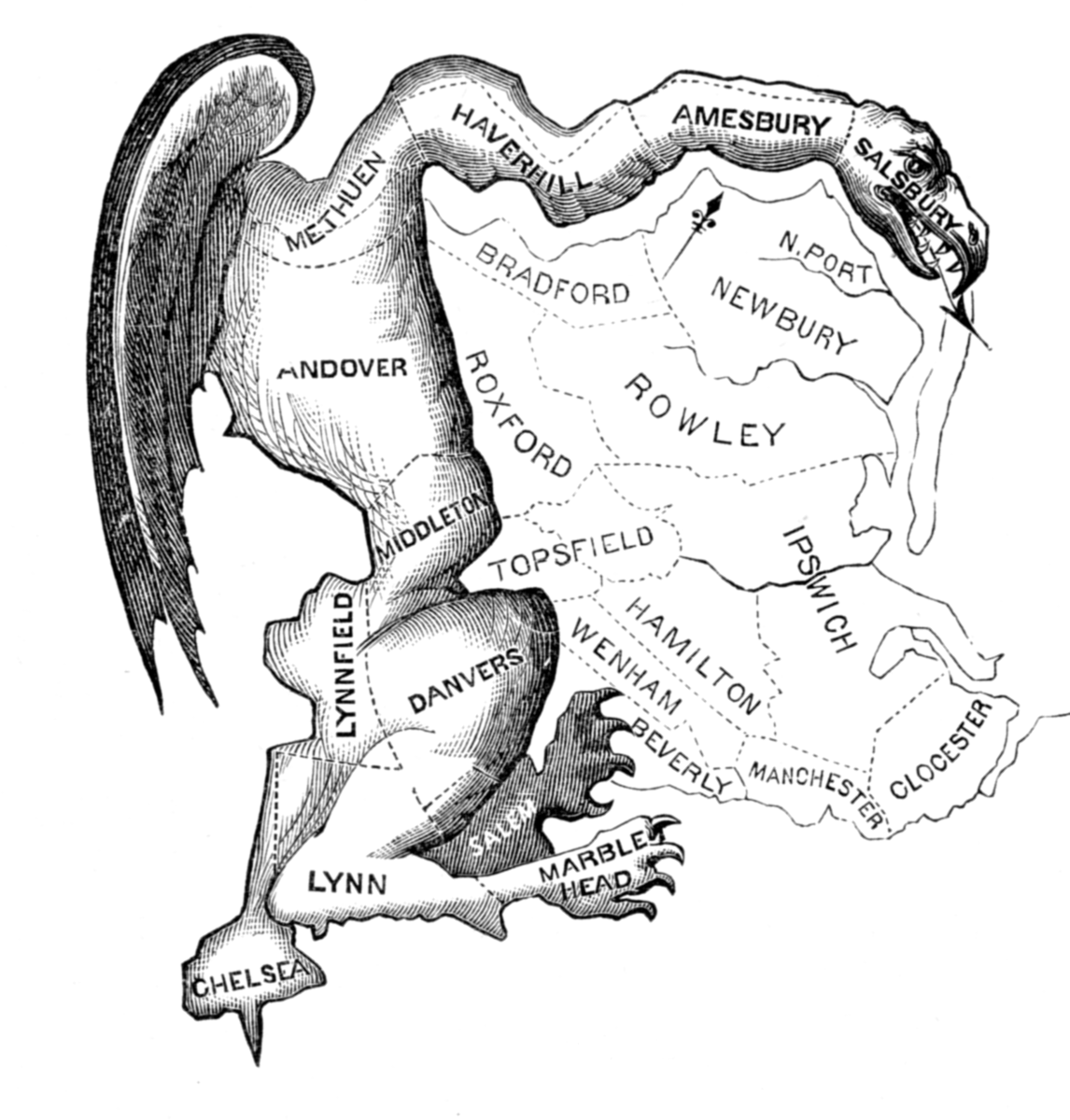

A gerrymander is defined as a manipulation of the boundaries of an electoral constituency so as to favor one party or class. In other words, a gerrymander involves a purposeful effort to skew the system to the advantage of one party, group or interest. Most of the gerrymanders in the news the past few years are partisan gerrymanders, where one political party controls the redistricting process and draws the district lines to its advantage. You can see how to gerrymander here.

Gerrymandering has been around for centuries (literally). And let us be clear: both the Republicans and Democrats in the U.S. have long histories of partisan gerrymandering. However, recent technological advances involving geographic information systems and personal data mining now make gerrymandering far more sophisticated and effective. It is now possible to distort the correlation between votes received and seats won in much more sophisticated ways.

This explains why each party wants control over the redistricting process, and why many states have created independent, bi-partisan or non-partisan redistricting commissions in the past 20 years.

WHAT ABOUT REAPPORTIONMENT?

The basic answer is that “reapportionment” means to “make into portions again,” and it usually refers to reallocating seats among the states in the U.S. House of Representatives. So, redistricting generally deals with state-level politics, while reapportionment usually has to do with our representation in the federal government. The number of congressional House seats is fixed at 435, so after every census, as some states have grown faster than others, a few of those seats get reallocated from one state to another.

Usually only about a dozen seats get reallocated, but this can have real political consequences. Most of the states that are gaining seats are in the South or West, and almost all the states that will lose seats are in the East and Midwest. This pattern has been in effect for several decades now, as the “sunbelt” areas continue to grow at a much faster rate than the eastern and midwestern states.

The population growth in Idaho has been substantial, but probably not quite enough to get an additional congressional seat for the state. From Idaho’s perspective, the timing of the census is unfortunate; if it were done in 2021 or 2022 instead of 2020, Idaho would probably get an additional congressional seat this decade. Since Idaho is unlikely to receive an additional congressional seat after the upcoming census, congressional reapportionment will have no impact here.

But, recall that reapportionment means “to make into portions again” and, therefore, if a state constitutional amendment increasing the number of state legislative districts were to pass in Idaho, that too would be a reapportionment (at least technically) because we would be changing the number of portions from 35 to some other number.

1. The quote is from Representative Linda Hartgen (Republican, Twin Falls). See Ryan Blake, “Legislative district maps up for discussion,” Twin Falls Times-News, January 5, 2020, p. E3.

Until his retirement last year, Gary Moncrief was a member of the Boise State faculty for 43 years. In 2004 he received the University Foundation Scholar Award for Research, and in 2011 he was one of the first faculty to be awarded “Distinguished Professor” status. His books include Reapportionment and Redistricting in the West (2011) and State Legislatures Today (3rd edition, 2019). He was a consultant to the National Conference of State Legislatures, the Council of State Governments, the State Legislative Leaders Foundation, and the Eagleton Institute of Politics at Rutgers University.