Scott Yenor is Professor of Political Science at Boise State University. He is the author of Family Politics: The Idea of Marriage in Modern Political Thought (Baylor 2011) and Hume’s Humanity: The Philosophy of Common Life and Its Limits (Palgrave 2016).

Many of those genuinely worried about the future of the American republic have vested hopes in a call for a new Constitutional Convention (aka Con Con) to fix perceived defects in contemporary political practice. Such advocates are overly optimistic about the prospects of a Con Con to deliver on such promises and have a misplaced hope that they will achieve through constitutional reform what has not been achieved through politics.

Those calling for a Con Con have legitimate grievances. There are serious problems with American constitutional practice relating to the erosion of the separation of powers, the self-effacement of congressional powers, and the practice of federalism. The advent of bureaucratic government, announced in principle during the progressive era and becoming the predominant mode whereby legislation becomes genuine law during the Great Society, has eroded public accountability and transformed Congress into an overseer of independent agencies more than a legislative or deliberative body. Many have written thoughtfully about these deep, serious, enduring, and seemingly intractable problems. A new constitution has, in effect, been grafted onto the old, compromising practice, undermining public trust, and exacerbating problems of consent. All is not well with the American Constitution.

Nor is American political practice obviously healthy. Budget deficits and public debt are at record highs. Public confidence in government is at a nadir. It is not clear that our government agencies accomplish what they set out to do, nor are there serious consequences if they do not. The status quo is, one way or another, unsustainable. Change must come, one way or another, to our constitutional system.

In response to this, calls are made for a new constitutional Convention—an Article V Convention—to address our serious problems. A Con Con would begin with two-thirds of states calling for a constitutional Convention. Congress is then required to call the Convention, just as the government of the Articles of Confederation had called the original Convention in Philadelphia. The Convention would organize itself and make proposals for amendments, which would then be passed on to the states where three quarters must ratify them. They would then become part of an amended Constitution.

THE MOST OFTEN STATED REASON FOR OPPOSING A CON CON IS THE FEAR OF A “RUNAWAY CONVENTION”

A runaway convention, where those assembled exceed their limited mandate and offer more fundamental revisions to the Constitution, is not without precedent in American history. The Constitutional Convention itself found an inconsistency in its mandate and happily did more than just “revise” the Articles of Confederation. It proffered new principles and a wholly new Constitution—one that even bypassed the Articles’ normal ratifying process (which required unanimous vote of the states). James Madison acknowledges the somewhat extra-legal character of the Philadelphia Convention in Federalist 40, where he concludes by arguing that “considerations of duty” to their country moved the Philadelphia delegates in absence of “regular authority.”

The worry about runaways is sown into any proposal for a convention. One sees this clearly through revisiting how the amendment process arrived in the Constitution. A method of amendment that bypassed Congress was the first proposed in Philadelphia as part of the Virginia Plan (May 29). While a complete discussion was postponed, George Mason, Elbridge Gerry and Edmund Randolph all spoke about the propriety of a state-centered ratification process. Indeed, the Convention itself approved a state-initiated call for a constitutional Convention as the only means to amend the proposed Constitution on August 6. The case seemed closed.

More than a month later, on September 10, just over a week before the Convention broke up, two of the Convention’s major movers argued for the addition of another process—one whereby two-thirds of each house of Congress would propose specific amendments which would then go to the states for ratification. It was a one-two punch. Alexander Hamilton insisted on the propriety of involving the national legislature in proposing amendments as it would be the “first to perceive and will be most sensible to the necessity of amendments.”

James Madison seconded Hamilton’s conclusion with an argument against the Con Con proposal. Madison “remarked on the vagueness of the terms, ‘call a Convention for the purpose,’ as sufficient reason for reconsidering” the state-centered approach as the only approach. “How was a Convention to be formed? By what rule decide? What the force of its acts?” A few days later Madison repeated his criticism: “Difficulties might arise as to the form, the quorum &c which in Constitutional regulations ought to be as much as possible avoided.”

In what was hardly their last collaboration, Madison and Hamilton got the Congressional proposal added, and the rest is history. Theirs has been the only way whereby the Constitution has been amended.

Madison saw that constitutional conventions are informal assemblies, even when they are brought together under formal legal authority like Article V. Conventions are only subject to the limits of those within the convention can agree to and what those outside will consent to. Conventions experiment. Perhaps they will yield only minor surgery. Perhaps major surgery. Those attending such a future convention might be given directions by their states (as had happened in the call for both the Annapolis and Philadelphia Conventions during the founding era), but those attending would be limited only by the bonds of honor: the would be free to propose what they will at a constitutional convention. Conventions are called because there might, in some desperate circumstances, be some need for a runaway convention.

In one sense, Madison’s worries about the legal processes of a future convention are rich with irony. Those in Philadelphia overcame questions of form, quorum, decision rules, and so forth. If the 56 in Philadelphia could overcome these problems, certainly future generations would also be able to come to agreement. Or so the argument goes.

Yet the irony is not that rich. The conditions that led to the successful convention in Philadelphia were quite unique—and hoping to get similar results in different conditions might lead to a ticklish multiplication of dangerous experiments. The Philadelphia Convention seemed like a miracle. Madison reflects deeply on what made the Constitutional Convention successful, and hence on what makes conventions successful.

Three conditions stand out from his discussion in Federalist 40. First, the delegates and the country was “deeply and unanimously impressed with the crisis.” A common understanding of the crisis prepares the way for some movement toward a solution. Such solutions do not, however, arise “spontaneously and universally from the people.” Instead, it is necessary for some “patriotic and respectable citizen, or number of citizens” to make “informal and unauthorized” proposals for the people to consider for an up or down vote. These leaders are patriotic (our second condition for a successful convention) and that the public respects these leaders and sees them to be patriots (our third). There was at the time of the Founding a collection of patriotic citizens tested by fire, whose disinterested love of country was plain for all to see. The citizens, who could not spontaneously arrive at such a proposal, could identify those patriotic citizens when they saw them and they were be inclined to defer to their genius.

Alexis de Tocqueville, the great French observer of America, shared Madison’s sense that the Constitutional Convention was a prodigy, and in much the same terms. As he wrote in Democracy in America,

The Federalists . . . in their ranks almost all of the great men the War of Independence had given birth to, and their moral power was very extensive. Moreover, circumstances were favorable to them. The ruin of the first confederation made the people fear they would fall into anarchy, and the Federalists profited from this passing disposition.

The people felt a more than a vague sense of what was wrong; there were “great men” possessing extensive “moral power” to effect a successful constitutional change, even though it went against the grain of American public opinion, perhaps. This is what is necessary for a wholesale constitutional change to work.

Let us apply these standards to the call for a Con Con today.

- Is there sufficient popular understanding of the problems of governance? NO.

- Is there sufficient popular understanding of the solutions? NO.

- Are there great, respectable leaders to lead a Con Con? NO

- Would the people respect those leaders as such? NO

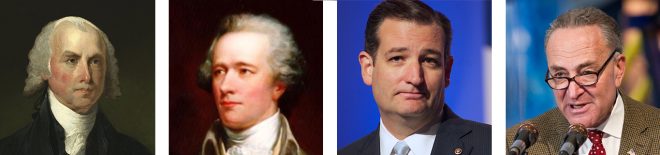

For these reasons, the Con Con is likely to be a waste of time and energy under our current conditions. There is no widely-perceived public ill aside from the sense that the country is headed in the wrong direction. There are scarcely widely recognized and respected public leaders who see beyond the technical fixes that afflict our policies. Efforts to find widely recognized, respected leaders are complicated through our quite polarized electorate: one side’s respected leader (e.g. Sen. Chuck Schumer or Ted Cruz) is the other side’s demon). We could use a man like Herbert Hoover again!

FOCUS ON THE NORMAL PROCESSES IS MORE LIKELY TO LEAD TO SALUTARY RESULTS

A Con Con is indeed part of the US Constitution and Madison’s reflections on the first Constitutional Convention should guide calls for a Con Con today. Article V is truly the most informal, revolutionary vehicle for constitutional change within the four walls of the Constitution. It is irregular, unregulated, and open-ended. It is, I think, just short of exercising the people’s right “to alter or to abolish” their government and “to institute new governments.”

One can understand that well-meaning fellow citizens turn to such desperate measures at a time when their national institutions do not appear to change overmuch after elections and where the amendment process seems closed given the power of the “Washington Establishment.” Only a Con Con could do.

Here, where the advocates for a Con Con seem most reasonable, we find the lullaby that the Con Con advocates must sing to themselves. “The people,” they must think, “are on our side. They understand the demands of good government and embrace all the costs necessary to bring it about. The government currently betrays the people. If the people could but make the rules, everything would be better. Budgets balanced. Legislators would be public-spirited. Bureaucracies would be brought under enlightened, popular control.”

If the public were genuinely alive and enlightened to all the implications of improving government, no Con Con would be necessary. Constitutional conservatives do not get the needful reforms they call for because, truth be told, the people are not (yet!) on their side. Advocates assume the task of reforming government in our late republic is easier than it is. Focusing on their lullaby, they do not engage in the hard task of convincing the people of needful, workable reforms nor do they undertake a long-term project of reforming government through enlightening public opinion. There are no technical solutions to the problems of modern governance. They all presuppose an enlightened, vigilant people. The job of enlightening and enlivening should be front and center among those convinced that the Constitution itself is threatened.