Dr. Rebecca Som Castellano is an Assistant Professor of Sociology at Boise State University. She earned her Ph.D. in Rural Sociology at The Ohio State University, her M.A. in Sociology from the University of Kentucky and her B.A. in interdisciplinary studies from Fairhaven College at Western Washington University. She has worked in a range of food system jobs, including farmers’ market management and farming. Her areas of expertise include rural sociology; the sociology of food and agriculture; gender and development; and stratification. Her current research examines farmer adaptation to climate change, as well as stratification in the changing agriculture and food system. She has been awarded regional and national awards, including a USDA National Needs Fellowship, a Rural Sociological Society Thesis Award, a Coca Cola Critical Difference for Women Award, and the American Sociological Association Community Action Research Grant.

Dr. Lisa Meierotto is an Assistant Professor in the School of Public Service at Boise State University. She teaches in the Global Studies and Environmental Studies programs. Meierotto earned her Ph.D. in environmental anthropology from the University of Washington, and also holds an M.A. in International Development and Social Change from Clark University. Previous research focused on the environmental impacts of undocumented immigration on the U. S. Mexican border. Current research focuses on human rights and environmental justice, especially considering the social and environmental ramifications of global migration trends.

Jen Schneider is Associate Professor in the School of Public Service at Boise State University, where she also directs the PhD program in Public Policy and Administration. Her research addresses challenges in the public communication of scientific and environmental controversies, with a particular focus on industry rhetoric and rhetorics of technical expertise.

Jillian Moroney is a postdoctoral fellow at Boise State University. She enjoys working at the interface between society and natural resources. Her areas of research and expertise include social assessment and stakeholder engagement regarding natural resource related topics including bioenergy, forestry, irrigation, and farmland. She earned her Ph.D. in environmental science and her M.A. in bioregional planning and community design, both from University of Idaho, and her B.A. in geology from Western Washington University.

Susan Medlin is Treasurer of the Treasure Valley Food Coalition. She is an educator, cook, gardener, and food enthusiast who has actively promoted local sustainable agriculture for many years.

Dramatic changes have been occurring in land-use (how land is managed and modified) across the United States in recent years. Urbanization has led not only to population increases in urban centers, but has also motivated the spread of urban development into rural areas, some of which had previously been used for farming. Thus, it is not surprising that across the United States farmland is disappearing, in large part because of urbanization. As population size in urban areas has grown, encroachment onto farmland has shifted land use towards recreation, housing, business infrastructure, and other forms of economic development.

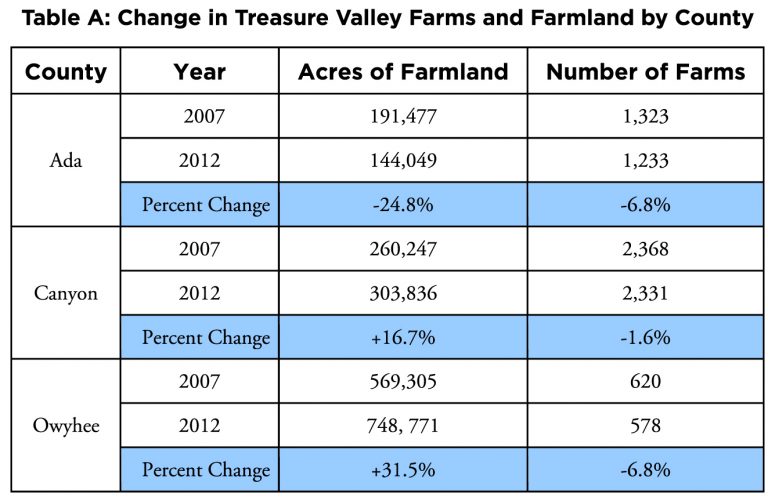

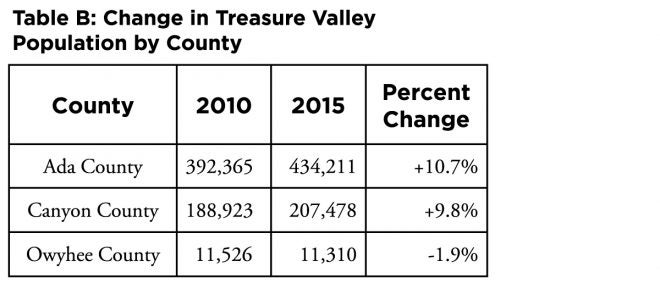

Data from the Census of Agriculture and US Census can help illustrate how land-use has changed in recent years in the Treasure Valley. As noted in Table A, the land in farms (by acre) in Ada County have declined in recent years, but have increased in Canyon County. On the other hand, Owyhee County, which is far more rural, has seen an increase in the number of acres in farming. Meanwhile, similar to other parts of the United States, the Treasure Valley is also experiencing population growth. As noted in Table B, both Ada County and Canyon County have grown by approximately 10% between 2010 and 2015, while Owyhee County saw a reduction in population size, down nearly 2% between 2010 and 2015.

Recent research published by scholars from Boise State offers insights about land-use change, population growth, and the decline of farmland in the Treasure Valley. According to the study, the outer edges of urban areas are rapidly expanding. This form of growth is outpacing “infill”–the ways in which cities can grow up, or become more dense. In other words, sprawl is our dominant mode of growth in the Treasure Valley, and in this process, farmland is disappearing.

These land-use changes have not gone unnoticed, and public concern with the social and environmental implications of urban sprawl in parts of the United States is increasing. But are residents in the Treasure Valley concerned with losing farmland in the region? And what is being done in the Treasure Valley about loss of farmland? In the remainder of this article, we will present recent research conducted on concern with loss of farmland in the Treasure Valley, as well as local efforts in the region working to preserve farmland.

CONCERN WITH LOSS OF FARMLAND IN THE TREASURE VALLEY

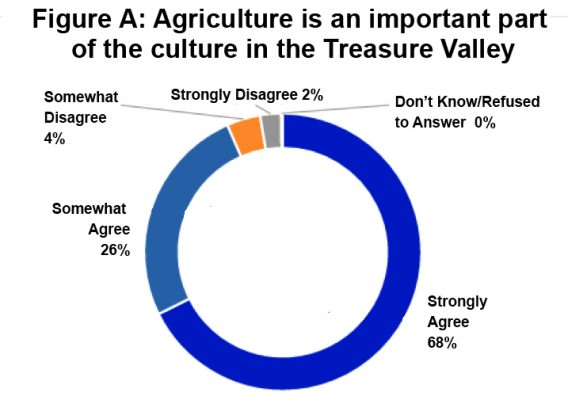

The 2016 Treasure Valley Public Policy Survey asked respondents a range of questions related to farmland, agriculture, and demographics. Even though almost 70 percent of participants were born outside of the Treasure Valley, 94 percent of survey respondents agreed that agriculture is an important part of the culture in the Treasure Valley (Figure A). While there is a need to further explore what residents mean when they say they are concerned about farmland in relation to culture, these survey results suggest that a large portion of Treasure Valley residents believe that farmland is important.

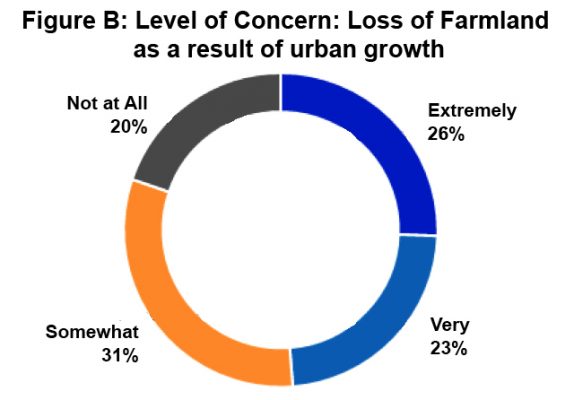

The Treasure Valley Public Policy Survey also asked “How concerned are you about the loss of farmland as a result of urban growth in the Treasure Valley – extremely, very, somewhat or not at all?” Survey results revealed that Treasure Valley residents are, in fact, concerned. Nearly 79 percent of respondents reported they were somewhat to extremely concerned with the loss of farmland as a result of urban growth in the Treasure Valley (Figure B).

This suggests, then, that there is widespread concern with loss of farmland in the Treasure Valley, perhaps because residents see agriculture as such an important part of the culture here, and feel less supportive of suburban sprawl. However, there may be more complexity regarding who is concerned with the loss of farmland. For instance, for political, economic or cultural reasons, rural residents may be more likely to be concerned with the loss of farmland. Many of the reasons people love rural life relates to the pace of life there, the feeling of being connected to a place, and the visual markers of a particular home place. It is therefore important to consider whether there are significant differences between rural and urban residents when it comes to concern with loss of farmland.

To that end, Som Castellano and Moroney recently conducted research examining whether there is a difference between rural and urban residents’ viewpoints on urban growth and expansion in the Treasure Valley. In a recent article, they ask the question “Are people in urban areas more concerned over the loss of farmland as a result of population growth, compared to their rural counterparts?” Using data from the 2016 Treasure Valley Public Policy Survey, statistical analyses were conducted in order to understand the ways in which concern with loss of farmland may vary by a range of factors, including geography.

Results from this analysis suggest that rural residents are more likely to be concerned with the loss of farmland. Som Castellano and Moroney also found that women and those with children in school were more likely to be concerned with the loss of farmland in the region.

In all, this research tells us that a large percentage of people in the Treasure Valley are concerned with the loss of farmland in the region, and that people residing in rural areas, women, and people with children in school are more likely to be concerned, relative to people residing in urban areas, men, and people without children in school.

This research could be particularly valuable for policy makers. Across the United States, communities are putting into place measures aimed at protecting farmland; such efforts are only in their infancy in the Treasure Valley. Below, we highlight the work of one local organization that is working to protect farmland in the Treasure Valley. Readers interested in such issues may want to become more involved with these types of advocacy efforts, or communicate their support for farmland preservation with policymakers.

FARMLAND PRESERVATION IN THE TREASURE VALLEY

The Treasure Valley Food Coalition (TVFC) is a non-profit organization dedicated to improving the resiliency, integrity, and economic vitality of the regional Treasure Valley food system. The TVFC works to educate the region about where their food comes from, inspire conversations about the externalities of increasingly industrialized agricultural systems, and demonstrate what local food can offer as remedy. In addition to a number of other organizations, including the Ada Soil and Water Conservation District, the Idaho Coalition of Land Trusts, and the Coalition for Agriculture’s Future, the TVFC has been working to promote farmland preservation in the Treasure Valley.

“Farmland preservation” has emerged nationwide as one possible policy solution, or set of solutions, to problems related to resilient food supplies and urban sprawl. The American Farmland Trust, which has taken up organizing and communicating about farmland preservation across the country, has inspired a number of organizations working to preserve farmland, including the TVFC, and there have been some notable successes Treasure Valley policymakers could draw from.

The issue of farmland preservation is undoubtedly complex. Much of the farmland in the Treasure Valley has qualities that make it desirable for development, including proximity to cities, beautiful views, water access, and large cleared expanses. Pressures from population growth and development can cause land prices to rise, and farmers who sell to developers may realize a (much) higher return on their acreage. Selling farmland can also help farmers get out from under debt or to retire; for some, this may be their only option.

Treasure Valley Food Coalition Events

In keeping with the ongoing commitment to raise public awareness and channel public efforts, the TVFC chose to organize a series of educational events this year for targeted audiences and the general public. Local planning organizations, Chambers of Commerce, elected officials, and interested academic researchers were contacted, and an agenda was set.

Two lectures kicked off the series in October 2016, one at Boise State University and one at the College of Idaho. These events highlighted the work and words of Mike McGrath, a retired planner from Delaware, who managed the work of the Delaware Agricultural Lands Preservation Foundation and led the Department of Agriculture’s efforts in statewide land use planning and agricultural development for 28 years. His efforts resulted in Delaware leading the region in the percentage of the state’s land area permanently preserved, including nearly 1/3 of Delaware’s farmland. These presentations by Mr. McGrath were attended by an estimated 250 people.

The next public event will take place on March 6 at 6:00pm in the Student Union Building, Jordan Ballroom, at Boise State University. Professor Tom Daniels will be providing a talk, titled “Public and Private Options for Farmland Preservation.” Professor Tom Daniels directs the program in Land Use and Environmental Planning at the University of Pennsylvania, and he administers the Certificate in Land Preservation. Professor Daniels is one of the leading thinkers and practitioners of farmland preservation. From 1989 to 1998, he managed the nationally-famous farmland preservation program in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. He is currently working on a book on the law of farmland preservation for the American Bar Association.

However, farmland preservation is one tool that can work to maintain farmland and provide economic support for farmers while also providing other benefits. For instance, there is a range of environmental benefits that can be gained from farmland preservation. According to the American Farmland Trust’s Disappearing Idaho Farmland report, environmental benefits of farmland preservation may include water quality protection, aquifer recharge, floodwater detention, riparian and upland habitat, wildlife migration corridors, and preservation of soil. While agriculture can have both positive and negative environmental impacts, agricultural lands have the potential to provide important ecosystem services when sustainable land management practices are utilized.

Farmland preservation can also benefit our community economically. It is much more expensive to provide public services like roads, sewers, and water systems to suburban developments than to agricultural lands. According to the Farmland Information Center, the median figures for every tax dollar collected on U.S. residential land was offset by $1.16 of costs for services; for every tax dollar collected on U.S. agricultural land, the cost of services was only $0.37.

While the above benefits generally apply to all communities including the Treasure Valley, we recognize that the Treasure Valley is unique, and local preservation is particularly important here. Here’s why:

- We have over a century’s investment in a water distribution infrastructure to enable agricultural activity in the high desert. It makes sense to utilize this irreplaceable asset.

- Agriculture is an important part of our culture, history, landscape, and economy. When we preserve farmland, we celebrate that shared history, and we ensure that future generations of Idahoans will have the opportunity to farm if they so choose.

- Popular bumper stickers read “No Farms, No Food.” Keeping agricultural production local offers us the ability to advocate for the cleanest possible agrifood system, crops with high nutrient values, and labor systems we can monitor and improve.

- The Treasure Valley has well-defined and non-negotiable land limitations imposed by topography: our surrounding mountains cannot be planted or leveled for development. This means that once our productive land is developed, we cannot get it back or move farms elsewhere.

The myriad environmental, economic and cultural benefits of local farmland preservation are clear. Further, the 2016 Treasure Valley Public Policy Survey indicates that the loss of local farmland is of concern to the majority of Treasure Valley residents. The task moving forward is to bring together academic researchers, community-based organizations, concerned citizens and political representatives to develop public policy that prioritizes farmland preservation. Upcoming opportunities to learn more about local farmland preservation efforts are described above.