Vanessa Fry serves as the Assistant Director of the Idaho Policy Institute and Assistant Research Professor in the School of Public Service. Before joining the Idaho Policy Institute Vanessa served as the Assistant Director for the Public Policy Research Center and Policy Innovation Fellow for the City of Boise where she conducted a feasibility assessment on using Pay for Success financing to address issues associated with chronic homelessness.

Gregory Hill is Director of the Idaho Policy Institute and Associate Professor of Public Policy & Administration. He completed his Ph.D. at Texas A&M University in 2006. Dr. Hill has extensive survey and research experience in the academic, public, and private sectors.

Craig Jones is a graduate research assistant for the Idaho Policy Institute, researching decision making regarding water resources in the Boise Basin and beyond. Craig is pursuing a PhD in Public Policy and Administration at Boise State, focusing on energy justice and the role of science in decision making regarding energy resources.

Lantz Brown is currently a first-year student in the Master of Public Administration program at Boise State University. He recently graduated with his Bachelor of Science degree in Anthropology, also from Boise State.

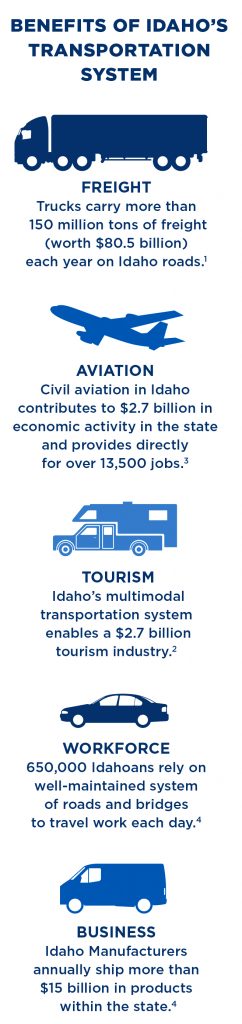

Idaho’s transportation system and infrastructure are vital to the state’s economy. Well-maintained roads, railroads, airports, transit systems, and ports allow Idaho businesses to manage inventories and transport goods more cheaply, access a variety of suppliers and markets for their products, and get employees to work. Reliable transportation infrastructure also enables consumers and visitors access to Idaho’s businesses and recreational opportunities. In addition, improvements to transportation infrastructure can help catalyze economic growth and positively impact employment, job creation, business retention and property development.

Idaho, like most states, is facing critical issues in its transportation system. Declining revenues and escalating debt service will reduce the state’s ability to maintain its transportation infrastructure in a state of good repair; resulting in a deteriorated road, rail, and aviation network, inadequate transit network, and a six- to ten-fold increase in repair costs (resulting from neglect and deferred maintenance). A number of studies have been done, including a report from the Governor’s Task Force on Modernizing Transportation, a that demonstrate the state of Idaho’s transportation system, shedding light on the repercussions of underfunding transportation infrastructure for Idaho as well as future transit needs of the state’s rapidly increasing population.

TRANSPORTATION AND THE ECONOMY

Idaho’s economy depends on a high quality, multi-modal transportation network. Transportation infrastructure investment has been proven to increase a state’s economic productivity. A well-developed transportation network can enhance job accessibility, reduce accident rates, and save time and money for employees commuting to work and therefore improve the quality-of-life features that make an area attractive to both employers and workers. This is especially critical for economically disadvantaged regions where improved infrastructure can reduce high production and transaction costs, which occur in much of rural Idaho.Infrastructure investment also can raise property values, particularly if these investments lead to the expected improvements in local living standards (including shorter commute times and greater proximity to desirable amenities). In fact, studies indicate that property values experience a premium effect when located near public transit systems.

Idaho’s roadways provide for the majority of the state’s transportation infrastructure (in both capital investment and miles traveled by goods and people). However, aviation, freight infrastructure, and public transit also play important roles. In addition to providing connectivity and increased accessibility, aviation is important to Idaho’s economic performance. It supports economic output, attracts business and tourism, supports local economic development, and retains jobs that might otherwise relocate. Forty-two percent of the state’s economy is comprised of Idaho’s freight intensive industries (e.g., agriculture, manufacturing, forestry, etc.). These industries rely on airports, rail, highways, and the Port of Lewiston to deliver goods within the state, across state lines, and to international destinations. Rail is a critical component of Idaho’s freight system for hauling bulk commodities, including agricultural products, basic chemicals (serving the food processing, wood, and chemical industries), fertilizers, cereal grains, and other agricultural products. Finally, public transportation provides over 4 million passenger trips each year in Idaho. Transit enables riders to pay a smaller percentage of their household income towards transportation costs and increases economic and social opportunities for residents and visitors who are economically, physically, or socially disadvantaged.

NO-ACTION CONSEQUENCES

Improving the way Idaho funds public investment in transportation infrastructure is critically important for the state. With a projected shortfall of $3.6 billion over the next 20 years, current funding levels are inadequate to maintain or expand Idaho’s infrastructure.

If new revenues are not identified and pumped into the system Idaho will face a rapidly deteriorating local highway system; ultimately leaving the local highways in an unusable and unsafe condition. These conditions could be catastrophic if nothing is done to augment the funding system.Annually, Idaho needs an additional $155 million dollars per year for operations and maintenance and an additional $207 million dollars per year for capacity improvements. The declining quality and poor performance of public transportation infrastructure systems impose significant costs on businesses and individuals and create bottlenecks that constrain economic development. Deferred maintenance of highways and bridges, due to inadequate funding and/or inefficient project prioritization, can lead to increased risk of accidents and even catastrophic infrastructure failures. Inadequate transportation infrastructure also can result in direct costs to Idahoans through vehicle repairs (e.g., damaged tires and suspensions) due to travel on roadways and bridges in need of repair and operating costs associated with congested travel, which also leads to reduced fuel efficiency.

Underfunding of infrastructure also can lead to an often unacknowledged consequence for state governments: increased risk of a credit rating downgrade. As emphasized by all three major US credit rating agencies, the economic base is a key factor in determining municipal bond ratings. Of the 4,427 bridges in Idaho, 876 (19.8%) are considered structurally deficient or functionally obsolete. Forty-five percent of Idaho’s roads are in poor or mediocre condition. Driving on roads in need of repair costs Idaho motorists $404 million a year in extra vehicle repairs and operating costs; that’s $379 per motorist annually.Job creation, income growth, and sustained economic development provide reasonable assurance that a bond issuer will be able to generate enough future revenue to repay its debt obligations, thereby enhancing the issuer’s creditworthiness. Through the linkage between infrastructure and a state’s debt and economy, large infrastructure deficits in quantity and/or quality may increase borrowing and limit the government’s ability to generate the necessary income to cover its debt. In addition, the poor condition of a state’s transportation infrastructure may reflect that state government’s inferior performance and inability to properly manage public assets.

INVEST NOW, SAVE LATER

A recent International Transport Forum report states that “deferring maintenance can make roadway costs much greater than indicated by current expenditures.” Supporting this finding, the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO) reports for every $1 spent to keep a road in good condition $6-14 are needed later to rebuild the same road if it has deteriorated. Despite this, transportation projects typically have been funded on a ‘pay-as-you-go’ basis due to the need to use revenue (primarily from a combination of federal grants and state and local taxes) to provide capital for a project.

Pay-as-you-go means that projects tend to be built over the course of several years as the revenue becomes available often delaying construction and making the repair more costly. To ensure more timely completion of projects some states have turned to financing strategies in order to access all necessary capital at the onset of a project.

States’ use of innovative financing techniques has resulted in projects being constructed more quickly than they would otherwise be under traditional pay-as-you-go financing. Financing has been used to address traditional infrastructure projects, such as for highways and bridges, and to support public transit. In addition, by prioritizing projects and having capital on hand to complete them, states are able to more proactively address issues with infrastructure and, ultimately, spend less and incur savings in the long run.

Idaho’s use of the Grant Anticipation Revenue Vehicle (GARVEE) program is a case in point. GARVEE bonds, an innovative highway bonding process, allowed Idaho to invest $857.6 million in highway improvement projects over a ten-year period, which funded, according to ITD Director Brian Ness, “. . . necessary improvements [that] would have taken 30 years under the existing pay-as-you-go method. But,” Ness added, “[Idaho] could not afford to wait — communities were growing, highway congestion was increasing and the funding options to improve Idaho’s transportation system were limited.” However, the GARVEE program in Idaho ended in 2015, necessitating a closer look into future funding and financing scenarios.

WITH CHALLENGES COME OPPORTUNITIES

By creating a strategy that permits more flexibility regarding infrastructure financing mechanisms, the challenge of fiscal stress can act as an opportunity to create a more flexible funding alternative. The transportation funding issue in Idaho, if viewed as an opportunity, can allow decision makers to think creatively and generate strategies that will both address the problems at hand and alter the way funding, as a whole, is considered. ITD has already moved in this direction in recognizing a sound infrastructure investment is one that ensures existing infrastructure is maintained in a state of good repair. However, If Idaho does not meet the increasing demand for transportation throughout the state, Idaho will be unable to be as competitive in the marketplace, the economy may be weakened, and the overall quality of life for the state residents will decrease. In order to remain competitive, Idaho can learn from the best practices of regional peer states regarding project prioritization process and funding strategies.

PEER STATES

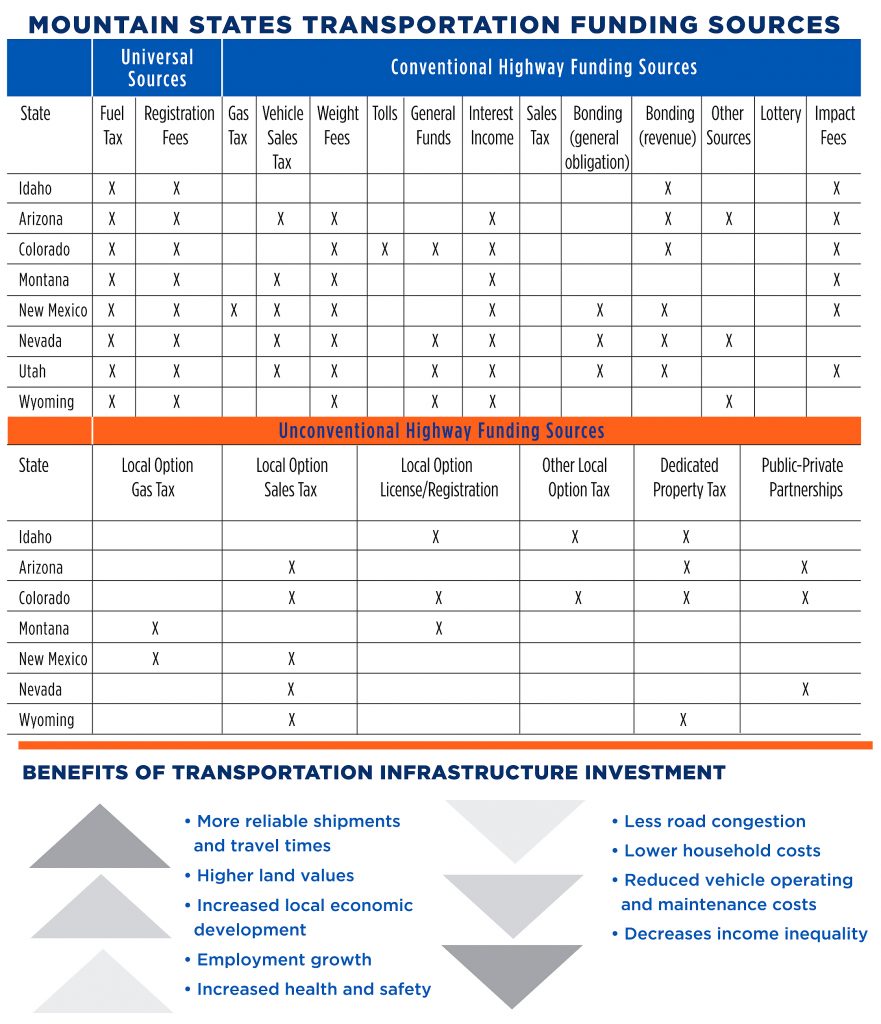

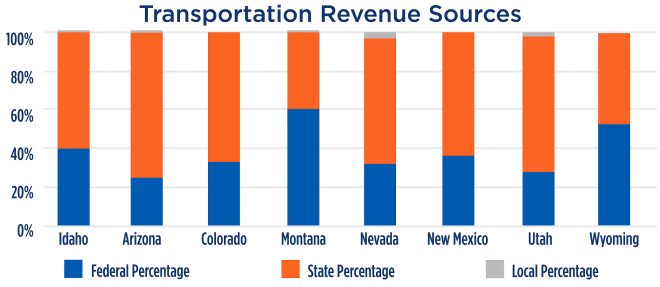

Idaho’s transportation infrastructure rating tends to be among the lowest among its peer states in the region including Arizona, Colorado, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming. Part of this may be due to Idaho’s heavy reliance on federal funding, which limits the state’s ability to meet both current and future transportation needs.

States typically finance construction, operation, and maintenance of transportation systems with a combination of federal, state, and local funding. Of the federal funding received by state departments of transportation, nearly 93% is through formula programs. The rest is allocated though discretionary grant programs, which are competitive in nature. The chart below compares Idaho to seven neighboring states: Arizona, Colorado, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah, and Wyoming.

UNIVERSAL FUNDING

All peer states are using two types of funding alternatives: fuel tax and vehicle registration fees. These traditional methods of funding are not sufficient to maintain the growing demands. Due to increased fuel efficiency and alternative fuel vehicles, states have seen a continual drop in fuel tax revenue, while at the same time seeing an increase in vehicles on the road. These are important dedicated funding streams, yet they sustain the pay-as-you-go philosophy and have contributed to the challenges Idaho faces today.

CONVENTIONAL FUNDING

This set of alternatives are considered “conventional” because a majority of Idaho’s peer states are employing them. However, Idaho’s use of them is limited to just bonding for revenue through the Idaho Housing and Finance Administration for the GARVEE bonds, impact fees, and other sources such as special plates, etc. There are many more alternatives that other states are doing.

NON-CONVENTIONAL ALTERNATIVES

The third set of alternatives is categorized as non-conventional because the usage is limited to a handful of states or the alternatives have not yet been implemented, but studies suggest that there are promising results. Increased funding is not the only option for policymakers. States are also seeking to reduce the need for additional revenue. Cost-saving strategies enhanced project prioritization, performance measures, demand reduction techniques, as well as balancing the need to maintain existing roads with the desire to build new capacity. In addition, innovative partnerships and land use development techniques have led to reduced costs.

CONCLUSION

Idaho is not alone in its struggle to maintain transportation infrastructure. Each of its peer states are trying to cope with deteriorating infrastructure, decreased revenue from dedicated fund sources, and inconsistent commitments from federal sources. As indicated, there are many ways that states can fund transportation infrastructure. One thing that stands out is that when compared to its peer states, Idaho uses by far the fewest number of options, in effect limiting the vision and opportunities that surround transportation funding. Many of Idaho’s peer states have implemented innovative funding solutions. Others are investigating ideas. It is clear from this analysis that there are many ways to approach this pressing public problem. It seems, legislatively, that Idaho has boxed itself in with respect to its ability to be innovative and non-conventional when it comes to the universe of policy alternatives that exist. As evidenced in a recent article in the New York Times, states are recognizing the federal government’s limitations on funding transportation infrastructure, and thus are looking inward for policy solutions. In fact, there are public transportation bills worth over $200 billion dollars on the November 2016 ballot. Utah, Colorado, and Arizona are listed as states leading the way.

Finally, one of the main challenges for Idaho, aside from the actual financial shortfall dilemma, is helping the citizenry recognize transportation infrastructure funding is a major problem. Recent surveys, statewide and in the Treasure Valley, have identified jobs, the economy and education as the main issues facing Idaho. Those surveys also noted those issues as the top priorities that the Idaho legislature should address. Transportation registered much lower than these other issues in both studies. However, jobs, economy, and education are inexorably linked to transportation and the infrastructure needed to support them.

Many organizations in Idaho are working hard to preserve Idaho’s transportation system. From Metropolitan Planning Organizations to local leaders to ITD, each group has a commitment to excellence. By engaging the citizenry and key transportation stakeholders regarding this issue and offering policy alternatives adopted by peer states, Idaho can move toward instituting new and innovative dedicated funding sources for the transportation infrastructure that is vital to Idaho’s future economic competitiveness and vitality.

Footnotes

- Idaho Transportation Planner (2015).

- Bureau of Transportation Statistics. (2015). State Transportation Statistics 2015. Data is from 2013.

- Federal Aviation Administration. (2015). The Economic Impact of Civil Aviation on the U.S. Economy. U.S. Department of Transportation.

- Governor’s Task Force On Modernizing Transportation Funding In Idaho. (2011). Final Report.