Editor’s Note: This article was edited in October, 2018 to incorporate PhD dissertation research by Ezra Temko.

A previous version included the sentence: “Kappie helped spearhead the Gender Balance Project in Iowa to pass gender balance legislation for state board appointments.” Temko’s research demonstrated that this was incorrect. The Blue Review thanks Wendy Jaquet and Ezra Temko for bringing this to our attention.

Gender balance legislation is one of the more promising efforts across the United States to increase women’s participation in elected office. This legislation, prominent in the state of Iowa, where it was enacted in 1987, and seven other states, encourages or requires state boards, commissions and councils to create gender balance in the hope that women will be more likely to run for public office after having served in these capacities.

Before running for the Idaho Legislature, I served on two state boards: The Idaho Commission on the Arts and The Idaho Job Training and Partnership Council as well as numerous city and county boards and committees. That early public service gave me experience in contributing to state policy, confidence that I could run and make critical decisions and introduced me to a statewide group of supporters for my campaign, including key financial supporters.

THE ERA LED TO GENDER BALANCE IN IOWA

The congressional passage of the Equal Rights Amendment in 1972, after a long, 49-year fight, was a benchmark for women across the country. During the ultimately unsuccessful ratification campaign, organizations such as the American Association of University Women (AAUW), the National Organization for Women (NOW), Women’s Political Caucus and the National League of Women Voters created active organizations of women across the country to work on gender equity and state passage of the ERA.

* On 6/26/15, we clarified several facts below, indicated with an asterisk (*), based on correspondence with Hammond.

Retired Iowa State Senator Johnie Hammond was first elected to a Story County, Iowa supervisor position in 1974 and served for four years. Active in her local women’s political caucus,one of her top election issues was to get more women appointed to county boards and commissions. Her “more women appointed” goal evolved into the notion of gender balance. “At that time women served on the Social Welfare Board, but not on the Planning and Zoning Commission, the Zoning Board of Adjustment, the Conservation Board, or even the Public Health Board. Conversely, men did not serve on the Social Welfare Board,” Hammond wrote in a personal communication that I recently obtained.

Idaho ratified the ERA on March 24, 1972 and later rescinded the vote on Feb. 8, 1977.

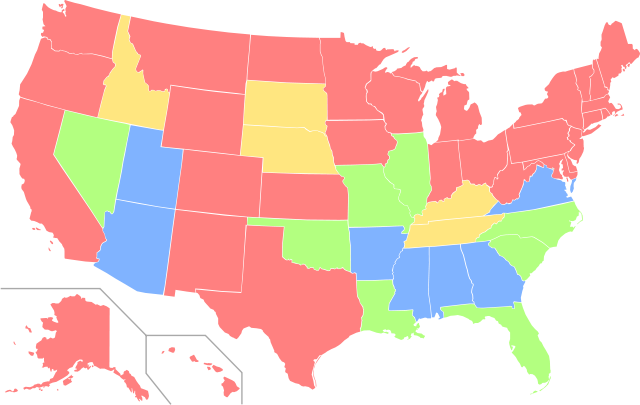

State support of the ERA:

Ratified (30 States), ratified, then rescinded (5 States), ratified in 1 house of legislature (8 States), not ratified (7 States).

Hammond went on to be elected to the Iowa House of Representatives in 1983. According to Hammond, after ERA ratification failed, President Ronald Reagan suggested that we could correct discriminatory laws state by state. Iowa Governor Terry Branstad supported this suggestion and in 1983 he assigned state attorneys to “clean up the code,” to neutralize gender references, to look for laws on the books that hurt women and to look in the state code for outright discrimination against women.

Once her legislation was introduced, with support from a bipartisan group of women,* it took Hammond three years to get a gender balance bill passed. In the interim, she attached amendments requiring gender balance to the governor’s appointments and to any new legislation requiring a state board or commission. They called it the “usual amendment,” according to Hammond.

In 1986, Iowa state government went through a massive reorganization.

The implementation bill was long and complicated and ended up in a House and Senate Conference Committee where, again, Hammond, as a member of the Conference Committee, attached her amendment, this time successfully. The Governor was so committed to the reorganization bill, as was legislative leadership, that they didn’t remove the gender language, Hammond stated. Hammond told TBR that the 1986 bill had a loophole that required gender balance, “as much as possible,” something the governor abused.* In 1987, Hammond and others returned to the legislature and “fashioned a clear and inflexible policy about those amendments,” Hammond recalls.

In 1988 Iowa amended the 1987 bill to require that boards have an even number of members. Today, Iowa can brag that all state boards, councils and commissions as designated in code are gender balanced.

James Madison argued in Federalist 51 that a truly republican government “be derived from the great body of society, not from an inconsiderable proportion, or a favored class of it.”

When it became obvious that Iowa women wouldn’t just sit around and wait for gender balance to happen at the local level, legislative agendas were created such as the League of Women Voters “Making Democracy Work” campaign in the 1990s. The campaign focused on five key indicators for success, one of which was diversity of representation.

Judie Hoffman, former* lobbyist for the Iowa League of Women Voters, pointed out that the national public policy position of the League of Women Voters was to “promote an open government system that is representative, accountable and responsive.” The Iowa group’s efforts were consistent with the national and they joined the Iowa Commission on the Status of Women (CSW) and the Friends of the CSW to lobby for extension of gender balance to local units of government and school boards. Although the city of Cedar Rapids had successfully enacted legislation to create gender balance on its boards and commissions in 1993, the League of Iowa Cities and the Association of Iowa Counties opposed the proposed amended state legislation, indicating that it was a mandate, according to representatives of both associations.

In addition, representatives of the cities and counties believed that certain boards and commissions leant themselves to male leadership, such as planning and zoning commissions and economic development councils. Some argued as well that other state panels called for a female gender bias, such as library boards and historical preservation committees.

“A woman’s approach to legislation is often closer to her constituency, developed through collaboration, and negotiated with more transparency.” L. J. Wurtz, 2012

Iowa has 99 counties and some are small with much smaller cities. They have trouble filling their boards and commissions with anyone, much less worrying about gender balance, said William R. Peterson, executive director of the Iowa Association of Counties.

EXTENSION OF GENDER EQUITY TO SMALLER UNITS

Iowa Representative Mary Mascher, a Democrat who carried the legislation to extend the state statute to local units of government, told me that the bill would not have passed the Iowa Legislature in 2009 if the Democrats had not moved to a unified majority. Having already defined the problem of a lack of female representation and generated proven policy proposals, Iowa Democrats found themselves at a critical juncture, what policy scholar John Kingdon calls the “window of opportunity,” allowing them a chance to set the legislative agenda.

Iowa’s coalition of AAUW, NOW, LWV, Iowa’s Commission on the Status of Women, the Friends group and the Catt Center at Iowa State University (corrected 6/11/15) thought that women would naturally move into the local government boards, councils and commissions as a logical outcome of the 1987 legislation. However, that did not happen. The coalition worked with representatives of cities such as Des Moines and Cedar Rapids to get the legislation extended to cities, replicating the policy across the state. The bill passed in 2009 with an effective date of 2012. Activism around the approval of the Equal Rights Amendment in the early ’80s created important policy coalitions and strategic proposals that primed the pump for statewide adoption.

THE POLICY ENTREPRENEUR

Lonabelle “Kappie” Kaplan Spencer was a 1947 graduate of Grinnell College. She lived in Des Moines, Iowa most of her life, but also lived part time in Sarasota, Florida. Her obituary indicates that she ran for the Iowa Senate in 1976, yet, as a woman, she could not be listed in the phone book.

“Women were simply invisible,” Spencer wrote. “The CEO [of the phonebook company] just laughed when I insisted that it change, and that was his mistake. I researched the directory and showed that the addition of women’s names in the directory would actually help to identify the Bob Johnsons, Smiths and Jones, and I proved that the telephone companies were actually losing money, losing revenue by their stubborn refusal.”

Spencer lost her race against the Senate majority leader, but captured one-third of the vote. Serving as the national legislative director and chair of the national board of directors for the American Association of University Women from 1978 to 1983 gave her entrée to lobbyists and other state leaders. Kappie helped spearhead the Gender Balance Project in Iowa to pass gender balance legislation for state board appointments. (see Editor’s note at top of article). During that time she also joined the National Women’s Political Caucus. Hammond indicated that Kappie traveled the country “preaching the gospel.”

Kathleen Wood Laurila, in the AAUW December 2012, newsletter had this to say about Kappie:

The Iowa law that passed in 1987 was initiated by Des Moines branch member Kappie Spencer at the same time she served on the national board of AAUW. With that success, Kappie began a campaign to achieve the same law in other states by networking with the national associations of commissions on the status of women, women state legislators and women philanthropists.Kathleen Wood Laurila

Kingdon calls actors such as Kappie Spencer “policy entrepreneurs” and points out that they “must be prepared, their pet proposal at the ready, their special problem well documented, lest the opportunity pass them by.” A policy entrepreneur, he says, needs to be able to speak for others such as a large and powerful interest group. Kappie Spencer did just that.

HOW POLICY SPREADS

The phenomenon of policy ideas passing from state to state has been the subject of much research. The theory put forth by Jack Walker in 1969 and then again in 1973 proposed an S-shaped diffusion pattern. Nicolson-Crotty (2009) summarizing Walker, points out that the diffusion pattern starts out gradually, involves learning, and then other state legislators, called copiers or adopters follow the leaders; re-election goals may also come into play.

According to the Center for American Women and Politics, Eagleton Institute of Politics at Rutgers University, women’s representation in state legislatures since 1971 has more than quintupled to 24.25 percent of 7,383 legislative seats in 2015; women hold 24.5 percent of statewide elective offices and 104, or 19.4, percent of the 535 seats in the 114th U.S. Congress.Nicolson-Crotty

The eight states that have gender balance legislation approved the policies, in most cases, around the same time, a few years after Iowa’s first legislation in 1987. First identified by retired State Senator Johnie Hammond, Kappie Spencer traveled not only to the states, but all over the world distributing packets of information about Iowa’s law.

“Probably my most important gift to women was the National Gender Balance Project, which I founded in 1988, based on an Iowa law made mandatory in 1987,” Spencer told the Veteran Feminists of America in a 2010 interview just before she died. “I created a packet and blanketed the U.S. with those packets containing a complete battle plan for getting the law passed in any state, and by 1995 it had already been passed in at least 15 states. Most recently it was brought down to the local level in Iowa – again the first in the nation. I also distributed them at state and national conventions, and even in Europe and Asia.”

A recent search through the National Conference of State Legislatures archives resulted in the following item from a February 1989 newsletter referring to Spencer:

Kappie Spencer, a national board member for the American Association of University Women, is conducting a nation-wide Campaign to adopt Iowa’s Gender Balance legislation in every State. The Iowa statute requires that the governor follow gender balance in appointing persons to state boards and commissions.

Several private organizations are following suit. So far Kappie’s efforts have resulted in introduction in California, Florida, Kansas, and Montana. If Kappie didn’t get a packet to you, contact your state Commission on the Status of Women. All directors have a packet of information as well.National Conference of State Legislatures

Gender balance states (according to The Carrie Chapman Catt Center):

- Iowa, 1987: The only state that has gender balance legislation applying to all levels of government (HF 243) extending the mandate to local government with conditions in 2009, effective 2012.

- Connecticut, 1993: (P.A. 93-424) state level only, “good faith effort” report due Secretary of State every two years.

- Illinois, 2000: (5ILCS 310/2) state level only, shall be gender balanced to the extent possible and to the extent that appointees are qualified to serve on those boards. If gender balance is not possible, then appointments shall provide for significant representation of both sexes to boards…”

- Utah, 1992: (Utah code 67-1-11) state level only, appointing authorities need to “strongly consider nominating, appointing, or reappointing a qualified individual whose gender is in the minority”

- Montana, 1993: (Code 2-15-108) state level only, “shall take positive action to attain gender balance and proportional representation of minorities in Montana to the greatest extent possible.”

- New Hampshire, 1992: (Code 21:33-a), state level only, “One of the factors which may be taken into consideration shall be the gender balance in the population which is served or regulated by the state office….”

- North Dakota, 1989: (NDCC 54-06-19), state level only, “should be gender balanced to the extent possible and to the extent that appointees are qualified to serve on those boards…”

- Rhode Island, 2007: (CODE 28-5.1-3.1), state level only, acknowledges the benefits of diversity and the enhancement when reflected and asks appointing authorities to “endeavor to assure that, to the fullest extent possible… reflects the diversity of Rhode Island’s population.”

Montana’s legislation, passed in 1993, provides further evidence of Kappie Spencer’s activities. Senator Diane Sands served as the Montana Women’s Lobby Director at that time and arrived at the idea of gender balance legislation from contact with Kappie Spencer and Iowa “in my old AAUW days,” as she put it:

I orchestrated a bill that requires gender balance and racial parity to the degree possible. We did it after looking at the hundreds of appointments and graphing out how many women and Native Americans were on boards and which boards. Women were predominantly on boards about children, never on the coal board or the board of investments or fish and wildlife commission. Besides equity and diversity arguments, we cited research showing that the path many women and minorities used to run for elected office was by first serving on appointed boards and commissions.Diane Sands

The Montana law also requires broad public posting of the openings. Sands indicated that the law, once passed, resulted in a woman immediately being appointed to the State Supreme Court.

To get the local government amendment to the Iowa bill approved, the sponsors agreed to preserve the ability of the local governments to re-appoint incumbents and to provide for a three month good faith effort prior to appointing once again the over-represented gender. Given that there are no sanctions to the legislation passed in 2009, the floor sponsor, Rep. Mary Mascher, conceded to a local paper, “but I don’t think any county will want to be out of compliance. The bill could not pass without the concession.”

STUDYING THE PIPELINE FOR WOMEN ELECTEDS

I suspect that states with gender balance legislation on the books will have a higher number of female officeholders who have taken similar pathways to office, starting with participation on boards and commissions at the local and state levels. Given a preliminary analysis from Iowa, it is projected that most women will demonstrate participation locally and not at the state level.

There are various efforts, including campaign schools created just for women candidates like the Iowa Carrie Chapman Catt Center’s Campaign School, Iowa’s 50/50 in 2020 effort and the Yale Campaign School to name just a few.

Recent research from Jackie Filla and Christopher Larimer (pdf of conference paper; study has since been updated) suggests that the states that do not have gender balance legislation will have fewer female office holders and minimal participation on local or state boards and commissions. Determining their pathways to office should create other pipeline options to be researched.

There appear to be a fewer organizations poised to help women run for office than in the early 1990s. Research on the activism of NOW, AAUW, LWV and other organizations is worth exploring. If women need to be “asked” and need supporting organizations to help them run, the lack of capacity of these groups may discourage women from running. Some states have continued to be more aggressive in getting women to run. Iowa’s Friends of the Commission on the Status of Women is working on creating a “Talent Bank.”

Connecticut’s Permanent Commission on the Status of Women worked to pass its gender balance legislation in 1993 after conducting a survey of state boards, councils and commissions to determine gender and race composition. To augment its Talent Bank, the Commission held two seminars in 1999 and grew talent by over 200 women. The Women’s Appointments Project’s state-based coalitions (ConnGAP in CT) are working with the governor to appoint women to 50 percent of the high-level positions in state government.

In Idaho, and about two dozen other states, the National Education for Women (NEW) Leadership program, developed by CAWP, introduces college-age women to political leadership.

Montana’s Carol’s List has created a “binder” of “highly qualified” women and works closely with the governor’s office on upcoming openings. Sands pointed out that Montana has achieved a high degree of transparency about upcoming openings.

A Women’s Caucus with bi-partisan membership may be key to proposing this type of legislation, as Hammond suggested. Under-represented women and members of under-represented populations need to see people like themselves in policymaking positions. The Clinton campaign should inspire women across the country to consider stepping up and participating in the governmental process. Finally, a supportive governor and legislature as well as an academic institution committed to women’s issues research appears to be critical for the implementation of the statutes.