In this piece, anthropologist John Ziker details the first stage of a study of faculty time allocation based on a self-monitoring survey instrument that uses time allocation reporting, a technique used by anthropologists in the field. The first phase of the study found that respondents — all professors at Boise State — spend a large amount of time in meetings and 30 percent of their time doing administrative tasks unrelated to teaching and research. Faculty work well over a 40-hour work week, including putting in time off campus and during the weekends. And they spend a majority of time working alone. —Eds.

The days of the ivory tower are a distant memory. We may hear about them from our ancestors — our teachers’ teachers’ predecessors who lived in the days when social philosophers wrote voluminous comparative works and most teaching was done in small groups in the Socratic tradition. But my mentors also taught me to be wary of idealizing the past. Discrimination, sexism and exclusivity characterized those times. And the theories of human nature that social philosophers and historians expounded back then were biased as a result. No, the ivory tower is not some golden era to which academics are striving to return.

But one concept from those days of yore — the principle of academic freedom — remains hallowed in the minds of most scholars. Without academic freedom, it is likely that the spirit of inquiry and intellectual development would wither away under the ever-looming “bottom line.” Academic freedom is what keeps Homo academicans stomachs full and mental juices hot. Without academic freedom, higher education faculty would have all the drudgery without the satisfaction of discovery. We love what we do, and if we don’t, we get out.

Now, the life and times of Homo academicus are morphing before our very eyes, along with the rapidly changing global economy, reductions of state support for state universities, the rationalization of the higher education “industry” and increasing pressure from online colleges. This is not just a U.S.-based phenomenon; it is a global one. Colleagues from the U.K. to the Russian Federation are increasingly saddled with a reporting burden — justifying their existence in spreadsheets — evermore concerned with journal impact factors, participating in multidisciplinary research and competing for external grant monies. What place does academic freedom hold in such an economically-oriented and competitive higher education world?

Sometimes, discovery takes many years, if not decades, and doesn’t have an immediate economic impact. Sometimes, we don’t even know when a discovery is significant until years after publication.

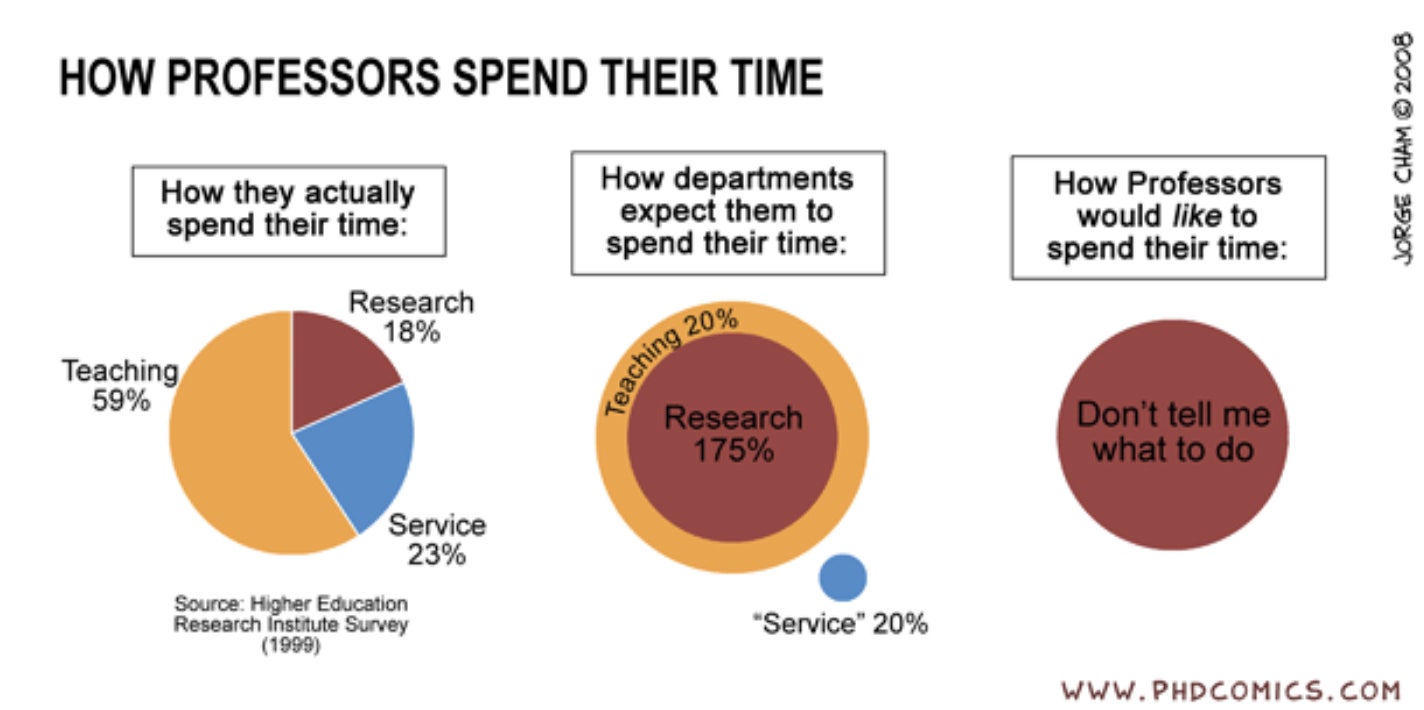

In addition to the importance of academic freedom, there is much debate (and tongue-in-cheek humor) at my own university and across higher education, about faculty workload. But we don’t have a reliable empirical basis for knowing how we spend our time and how that relates to our own productivity. Milem, Berger and Dey showed that professors are spending less and less time advising and counseling students, among other findings in 20 years of national survey data. “For example, state legislators and public opinion frequently mandate that faculty focus on teaching, whereas patrons of research (e.g., private industry and foundations, federal research organizations) promote and reward research activity and productivity” (Milem, Berger and Dey in “Faculty Time Allocation: A Study of Change over 20 years” in The Journal of Higher Ed.

Faculty are commonly required by state and university policies to have a particular workload distribution with a certain percentage of time dedicated to teaching. At my university, the standard proportion of time we are expected to dedicate to teaching is 60 percent with the remaining allocated to research and service. Different arrangements have to be negotiated and approved by administrators. Then, at the beginning of each year we are required to report to our administrators the proportion of time we spent doing what, how many classes, how many students we taught, how many and quality of publications, on how many committees we served, etc. I call this the “administrative-reporting approach” to workload. One problem with this approach is that it doesn’t take into adequate consideration all that goes into succeeding in an incredibly diverse array of disciplines.

Another problem is that the administrative approach doesn’t take into consideration the absolute amount of time that faculty spend working — that is, the number of hours. We are not generally organized like lawyers or doctors who charge clients by increments of time or procedures geared for profit. A lot of our activities are multi-purposed, and we can work at all times. Most members of the Homo academicus clan have only ballpark estimates of how much they work. This can create problems for “work-life balance,” especially for younger faculty. We are motivated to gain tenure and promotion not because this is a job for life, but because with tenure there is a degree of safety that allows faculty to experiment with new ideas and exercise academic freedom in teaching, research and service.

A final problem with the annual reporting approach to workload is that it doesn’t help Homo academicus improve their own productivity with much responsiveness. Administrators annually respond with a positive or negative evaluation of the faculty annual report, and they may make recommendations in seriously challenged cases. Now, reporting is made easier with web-based interfaces that help us keep track of our duties, publications and service commitments. The administrative-reporting approach is geared to fulfill requirements, not increase generalizable knowledge.

Being an anthropologist, I couldn’t just leave it at that. I thought to myself, why not apply some of our cutting-edge methods to study Homo academicus? What about faculty taking more accountability for their own performance? What if we had tools that could assist us in doing so? I am thinking about an analogue of something like the heart rate monitors and GPS watches that are used by performance athletes in their training. Self-monitoring helps maintain focus on continuous self-improvement. Is a self-monitoring approach to performance a way that academic freedom could be preserved into the future for Homo academicus?

As higher education faculty in the U.S., we enjoy many benefits, beyond our salaries, for which I personally am very grateful. I was reminded of these on a recent trip abroad when an immigration officer asked how I could afford to be away from work for a month. I said simply that we were on winter break and the officer jokingly lamented about going into the wrong profession. I didn’t mention to him that I had busted my tail over the week (and weekend) before departure, commenting on and grading final essays for a class of one hundred students, then figuring final marks and carefully uploading these marks into the university’s data management system. The work of modern Homo academicus is not a nine-to-five job. Many of our best thoughts come at 2:00 a.m., like the impetus for the project that I am about to describe. I am lucky I am at a university that values academic freedom, something that is highlighted in the preamble to our updated faculty constitution, approved by a faculty-wide vote and our administration in 2011, especially when researching a topic that is potentially as contentious as this one.

STUDYING THE STUDIERS

I thought this could turn into a really interesting research project. (Debate is usually a good sign of fertile ground for research.) I could practice putting together a team, argue for some seed money, train some students in methods and have them work as research assistants. Students would get some research experience. Faculty participants might get some interesting information about their work habits out of it, and the university would have summary data collected by a novel approach. If we could develop a tool that might help faculty be more productive as a result, no one would complain. One thing that some faculty were concerned about as we began the project was the university peering into the individual results and using these for evaluative purposes. The project had to be a win-win for everyone.

So, this was how the idea for the TAWKS project was born. TAWKS stands for Time Allocation Workload Knowledge Study. The idea was to use time allocation techniques to better understand faculty work patterns and productivity. These techniques are quite different than a standard survey or questionnaire, or post-hoc reporting. Time allocation techniques are good for developing statistically valid observational samples of how people spend their waking hours, which then can be related to any kind of outcome. Mark Flynn’s 1988 study of a rural village in Trinidad is a great example. With more than 24,500 behavioral observations in a small village, Flynn found that 11 to 15 year old daughters were chaperoned by co-resident fathers more than girls without co-resident fathers, and that the daughters with co-resident fathers had significantly more stable marriages to significantly wealthier men. During summer 2012, I had taken a course on time allocation methods sponsored by the National Science Foundation — the famed short courses on research methods in anthropology held at the Duke University Marine Lab — so time allocation was on my mind.

And, the acronym for the project turned out to be pronounced like “talk,” which is something faculty like to do. I thought that was a good sign. So, I began to put together a team and to look for funding in Fall 2012. I asked two colleagues in my own department, Kathryn Demps and David Nolin, who are familiar with time allocation methods, to join in on the project, along with Matthew Genuchi from Psychology. Genuchi was on Faculty Senate at our university in Fall 2012, when a new university workload policy was brought forward for consideration, so he was well aware of workload issues. The new policy intended to clarify the ambiguities in the previous policy. However, there was a flurry of debate about the new workload policy because of its default requirement for 60 percent teaching, equivalent to three courses per semester. Some faculty felt that such a policy contradicted the university’s goal of becoming a metropolitan research university of distinction, a vision many faculty were excited about and had followed for 10 years under our university president, Bob Kustra. The policy passed before debate gained any traction, and departments set out to write departmental workload policies that reflected the new university policy. Later, Genuchi found some additional professional interest in the self-monitoring part of the study.

Our college dean at the time, Melissa Lavitt, was interested in the topic of faculty workload for a couple reasons. The new university workload policy required every department to develop its own workload policy, and submit it for approval (or revision) to their college dean and the provost. Obviously, there can be big gaps between policy and outcomes. So, Lavitt, being interested in raising the level of research output from the college as a whole, wanted to understand how work habits played into variable outcomes across faculty and departments. Lavitt had been looking into research on faculty productivity for a couple years. One result that she had highlighted in several college-wide meetings was that faculty who had good research networks were generally more productive across teaching, research and service. Interestingly, this research showed that faculty productivity might not be explainable as a simple “zero-sum game” (more time for teaching meant less time for research), although that’s how some faculty looked at it.

As a way to foster such networks, Lavitt had been supporting interdisciplinary projects involving college faculty from more than one department through small seed money grants. We were eligible for such a grant with this project, so we asked for money to start the project. We started with the goal of simply figuring out what faculty do across the university, along with generating some preliminary empirical data on how much time subjects spend on these things, when, and where. I will summarize the findings from this first phase of the project further below.

In order to do this phase of the study, we used a modified version of the 24-hour recall technique. Listen to this NPR story about a sociologist who used this technique to study religion in the U.S. Also, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics Americans Use of Time Project. This technique takes the form of a structured interview during which the subject is asked to report everything they did the previous day beginning at 4:00 a.m. until 4:00 a.m. the current day, estimating time intervals as closely as possible. This technique is better for capturing rare and common activities than the time sampling method, so we wanted to start with this more descriptive technique. As this project was focused on work activities, everything that was not work was to be coded simply as “personal” time. We sent out a recruitment email to the entire faculty at Boise State (approximately 550 faculty members), and within a few days 30 faculty members across all colleges had agreed to join the study. While this was not a representative sample of the entire faculty, we thought this would be good enough to come up with the categories of activities we needed for the next phase of the project involving time sampling. We put out advertisements to students to apply to work as research assistants. We had 14 students reply to our ads, most of whom where anthropology majors enrolled in the field methods course that semester, along with a good number of psychology majors. Demps, Nolin, Genuchi and I conducted a daylong training session with the students on a Friday, and matched the students’ available times with those of our faculty subjects.

The next Monday, April 9, our team of student research assistants set out across campus to begin two weeks of interviews. The interviews were scheduled on alternating days over the two-week period, so the time taken for the interview did not appear on the previous day’s report (or in our data). Ideally, we planned to generate a report for each day of the week for each subject. Interviews that were scheduled to take place on weekends or when the faculty member was out of town were allowed over the phone. Fourteen faculty participants provided the full seven days’ worth of data. Sixteen faculty members provided from one to six days’ worth of data. With our initial 30 Homo academicus subjects, we ended up with a 166-day sample with each day of the week well represented. We were very happy with the result. The students had an intense research experience and got paid for their time. Dealing with thousands of entries and figuring durations of activities was a daunting task.

We assigned an anthropology graduate student, Marielle Black, to help code the data and create a database during the summer. One of the issues that came up in the Phase 1 data was the slight variation in descriptions used. Different participants referred to their activities with some variety, such as “checking email” versus “answering email.” In addition, the same participants reported the same activity differently on different days. This made dealing with the data to produce individual reports and to make comparisons across faculty and colleges difficult. In order to deal with these problems we eventually developed a coding scheme that categorized the practice (type of action) and the function (purpose) of each activity. After much discussion and a few afternoon-long sessions, we settled on 24 practice categories (other than personal time), nine functional categories and 11 categories that describe “with whom” activities are done. We aimed to have a limited number of practices and functions, so a number of “rare” activities ended up being combined into one category (i.e., Scheduling/Planning).

While we cannot make a claim that all faculty have the same work patterns as our initial subject pool — they do not comprise a random sample — the results are highly suggestive because of the consistency across our subjects who did represent. These results also provide a baseline to which we can make comparisons when we start the next phase of the project. More about that below, but first I’d like to us summarize the main findings from TAWKS phase 1.

HOW MUCH DID OUR HOMO ACADEMICANS WORK AND WHEN?

Few other professions fuse the personal identity of their workers so intimately with the work output. This intense identification partly explains why so many proudly left-leaning faculty remain oddly silent about the working conditions of their peers. Because academic research should be done out of pure love, the actual conditions of and compensation for this labor become afterthoughts, if they are considered at all.

— Miya Tokamitsu, In the Name of Love

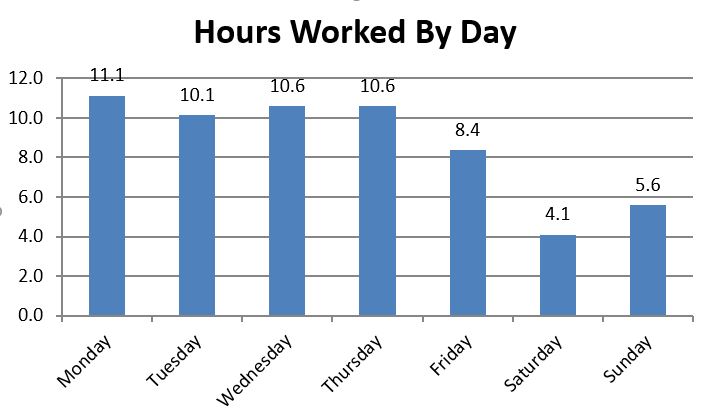

On average, our faculty participants worked 61 hours per week. That is 50 percent more than a 40-hour workweek. It’s a good thing they love what they do. They worked just over 10 hours per day during the workweek and just under 10 hours on the two weekend days combined. Work was heaviest on Monday through Thursday, trailed off on Friday, then maintained approximately a half-day load on the weekend. Now, someone might be thinking, “Well, sure, faculty work more during the semester, but what about during their winter, spring, summer and fall breaks?” I cannot address that question with current TAWKS data, but from my own experience, I can say that the breaks are when I get most of my research and writing get done (such as the essay that I am currently writing). But this is something that we’re interested in looking at during future phases of the study. All charts below are from TAWKS Phase 1 Stats, initial survey of 30 higher ed faculty from Boise State University. While findings are highly suggestive, they do not represent a random sample.

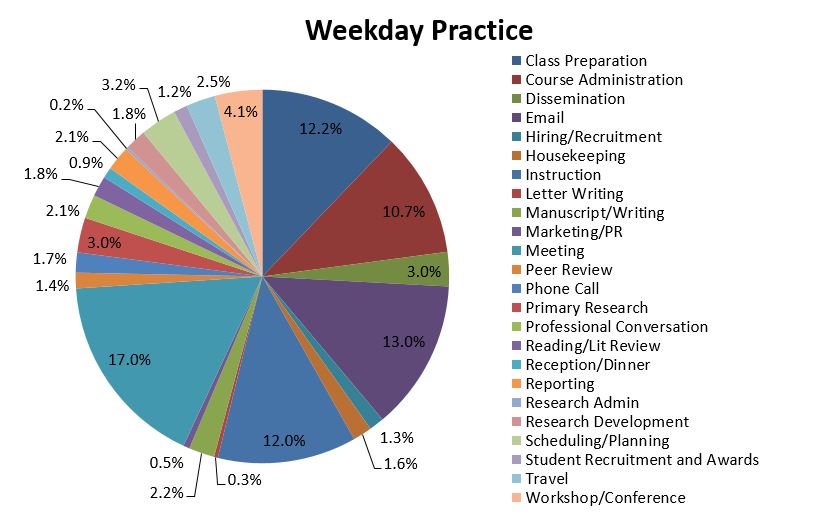

WHAT DID OUR HOMO ACADEMICANS DO WHEN WORKING?

The most surprising finding of our analysis of practices was that faculty spent approximately 17 percent of their workweek days in meetings. These meetings included everything from advising meetings with students (which could be considered part of teaching or service depending on the department) to committee meetings that have a clear service function. Thirteen percent of the day was spent on email (with functions ranging from teaching to research and service). Thus, 30 percent of faculty time was spent on activities that are not traditionally thought of as part of the life of an academic. Twelve percent of the day was spent on instruction (actual lectures, labs, clinicals etc.), and an equal amount of time was spent on class preparation. Eleven percent of the day was spent on course administration (grading, updating course web pages, etc.). Thus, 35 percent of workweek days was spent on activities traditionally thought of as teaching. Only three percent of our workweek day was spent on primary research and two percent on manuscript writing.

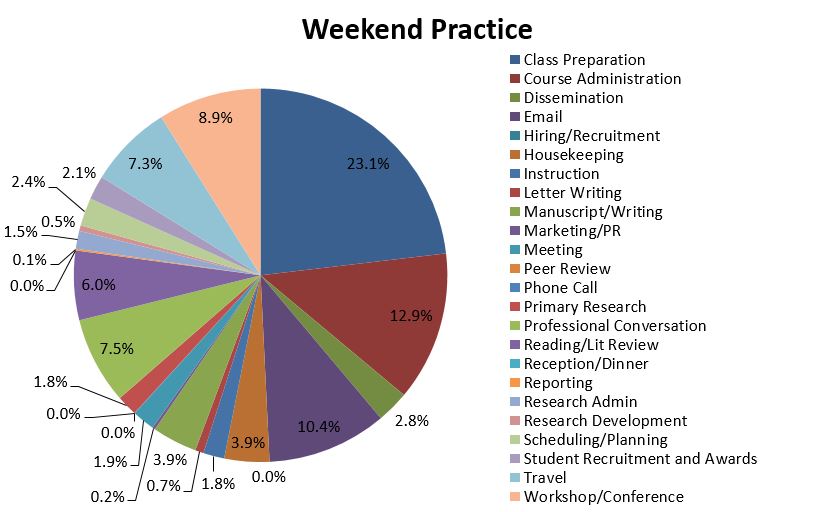

On the weekend, faculty spent 23 percent of their time on class preparation, 13 percent on course administration, 10 percent of their time on email, nine percent of their time at workshops/conferences, eight percent of their time in professional conversations, seven percent of their time on professional travel, four percent of their time on manuscript writing, and four percent of their time on what we termed housekeeping, which included cleaning up files, straightening offices and labs and updating computers, among a myriad of other more rare activities.

Combining workweek and weekend, our faculty subjects spent approximately 40 percent of their time on teaching-related activities, or about 24.5 hours. Interestingly, 24.5 hours per week is almost exactly 60 percent of a 40-hour workweek. So, what is happening? Are faculty shirking their teaching duties, or is workload policy geared for a time and place when success was defined largely by teaching? Research, it seems has to fit in outside normal working hours for our academicans. Only 17 percent of the workweek was focused on research and 27 percent of weekend time. However, it is research, and the external funding and recognition it brings, that makes a university a desirable destination for prospective students, particularly Ph.D. students. Our academicans definitely have an entrepreneurial spirit, a willingness to exploit their free time for work.

WHERE ARE HOMO ACADEMICANS WORKING?

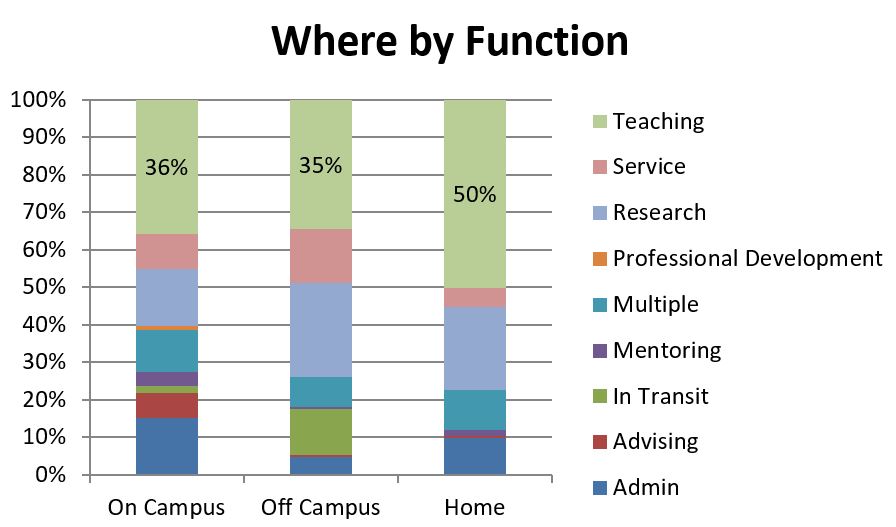

Most of our subjects’ work is conducted on campus (59 percent) but a significant amount of work is conducted at home (24 percent) and other off-campus locations (17 percent). In interpreting this data it is important to recall that subjects worked an average of 61 hours per week. So, despite spending a substantial amount of time working off-campus, our subjects still spent about 36 hours (59 percent of 61 hours) on campus.

WITH WHOM ARE HOMO ACADEMICANS WORKING?

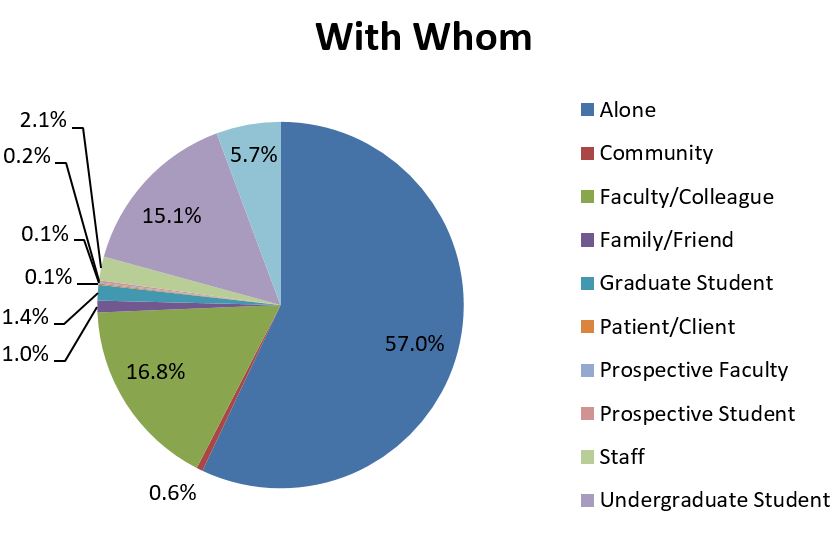

We amended the 24-hour recall diary to include a question about with whom our subjects were working. The surprising finding was the amount of time spent alone (57 percent). Only 17 percent of participant time was spent doing activities with colleagues and 15 percent of our time was spent doing activities with students. Being a faculty member appears to be a lonely occupation. When faculty were working with other faculty members, the main activities were meetings (44 percent), professional conversations (12 percent), co-attending conferences/workshops, and research dissemination (five percent). If we break meetings down by function service predominated (47 percent), followed by administration (25 percent), research (15 percent), and teaching (four percent). As we saw with the overall analysis of faculty practices, academicans spend a lot of time in meetings and doing service and administrative tasks. Collaborative research and especially teaching appears to take a back seat in faculty meetings.

This data illustrates that the work of faculty members was more complex than represented in workload policy and annual reporting activities. These results suggest that Boise State faculty work substantially more than the 40 hours per week. Are scientists workaholics? Our study participants spent the largest portion of their time during the week on teaching-related activities and a much smaller proportion of our workweek time on research. Weekends were times to prepare and catch up on courses, as well as conduct research. Faculty also spent a substantial amount of time working off campus – work that may be less visible to their colleagues and administrators. Many activities spanned a number of functions or were simultaneously multifunctional.

HOMO ACADEMICUS ON THE ROAD TO THE FUTURE

In order to better understand how workload time allocation is related to productivity in a novel way, Phase 2 of this project will utilize a mobile smartphone application that we’ve developed in collaboration with our Information Technology department (thanks to another small grant from Dean Lavitt). The second phase of the project will use the “experience sampling” method. As a type of time sampling, this technique generates a large number of instantaneous snapshots of what people are doing. This involves a minimal time commitment on the part of our subjects. After logging in and completing a short registration questionnaire, phase 2 subjects will begin to receive randomly generated text messages (“requests”) asking them whether or not they are working at that time they receive the text. If they answer yes, then they will be asked to report the work activity they are engaged in, the academic function of that activity, the categories of people they are working with, and the place they are working (on campus, off campus or at home). The TAWKS mobile app utilizes the categories of activities developed as a result of the Phase 1 study, and to reduce confusion, definitions of categories are available if they hover over the term. Phase 2 will include a daily self-report about satisfaction with the day’s productivity at the conclusion of each workday (the exact time to be set individually by each participant). Linking time allocation to productivity will allow us to investigate a number of ideas about what makes for successful and happy faculty.

The ivory tower is a beacon — not a One World Trade Center, but an ancient reflection of a bygone era — a quasar. In today’s competitive higher-education environment, traditional universities and their faculty must necessarily do more and more, and show accomplishments by the numbers, whether it be the number of graduates, the number of peer-reviewed articles published or the grant dollars won. It is harder to count — and to account for — service and administrative duties. These are things we just do because of the institutional context of Homo academicus,and it’s hard to quantify the impact of these activities or the time spent, but they are exceedingly important for intellectual progress of the larger Homo clans. Granting agencies and academic journals would be hard pressed if there weren’t faculty willing to provide reviews for proposals and manuscripts. Not to mention, many community organizations on which faculty serve as board members, advisors, speakers, essentially volunteering their time, would suffer were it not for this service. This is why academic freedom in teaching, research, and service is so important going into the future for Homo academicus. The research on faculty workload will continue; we need to get a better idea of how faculty spend their time at work and what patterns of activity are associated with greater levels of satisfaction. Faculty must innovate in order to meet increasingly complex demands. My collaborators and I hope to develop a tool that will help faculty reflect more frequently about their work patterns and productivity. Promoting accountability to self demonstrates academic freedoms and provides a way to augment the reporting approach to workload that is likely not going away. If we can make the road of Homo academicus less lonely in the process, it won’t seem long at all.

Acknowledgements: I am honored to acknowledge the contributions of our 14 student research assistants and the 30 faculty participants in phase 1 of the study. I thank my collaborators Matt Genuchi, Kathryn Demps and David Nolin. David Nolin came up with the Homo Academicus terminology, a play on Homo Economicus, though there is a book of the same name, and conducted the data manipulation and statistical analysis.