Cybersecurity education has been trailing behind other educational departments in one main factor: real-world experience. Let’s picture the process of becoming a nurse. Nursing students go through a process of developing knowledge by attending courses required to earn a Nursing degree. In these courses, they have a lecture portion discussing the contents of the textbook and building their knowledge in the topic. Then, the students begin the skill development process by going through practice simulations–such as practicing injections with artificial skin or examining cadavers. As courses come to an end, students complete clinicals, an experience in which a seasoned professional oversees the nursing student’s interaction with patients and responsibilities across the hospital, giving advice and guidance where needed. This vital capstone experience provides students with the opportunity to perform duties expected of them in future jobs under the supervision of accomplished professionals. Finally, after this rigorous experience, they are prepared to enter the workforce.

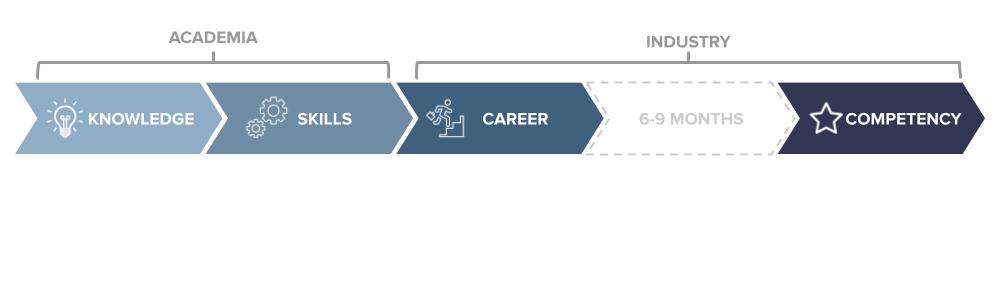

Comparing that in-depth training model to current cybersecurity training, we arrive at Figure 1, pictured above. Showcased here is the process most cybersecurity students experience in their academic and certification programs. Students pursuing a career in cybersecurity attend courses to gain knowledge, take part in simulation labs, and are then put directly into industry, missing significant practical experience. There is an obvious step missing when compared to other professions. With little to no clinical experience, these cybersecurity students are expected to secure and protect critical assets and data across the country. This leaves our country vulnerable to cyber attack as these new professionals find their footing in the industry.

Why isn’t cybersecurity afforded the same options to gain practical experience as other professions? From an employer standpoint, the demand for a cyber workforce is so high that most applicants are considered, regardless of capabilities. Additionally, employers believe that the quality of cybersecurity students is below average when exiting academia and expect instructors will never reach the competency level of other professions. As a result of this acquiescence, cybersecurity leaders across the country have reported spending between six to nine months enhancing entry-level cybersecurity professionals with the necessary skills and knowledge needed to be competent in the industry. These six to nine months are crucial because during that time the employee is not “active” and is nearly unusable in the role they were hired. These companies now shoulder the burden of the revenue loss while waiting for an employee to become “activated” in their role. Moreover, after activation there is a higher risk of employee churn as these now activated employees can command higher salaries elsewhere with their newfound skills.

Further complicating this process is the federal push that cybersecurity workforce development could be aligned to apprenticeships because there is belief that cybersecurity is a “technical trade.” There are similarities, but there are obstacles that make this view problematic. One such reason is that cybersecurity jobs require holistic development of essential skills (e.g., communication, analysis, etc) that fall outside the scope of many entry-level trade roles. Instead, the field of cybersecurity requires more focused attention on mentorship and practical applicability within academic institutions so that this burden does not fall on industry.

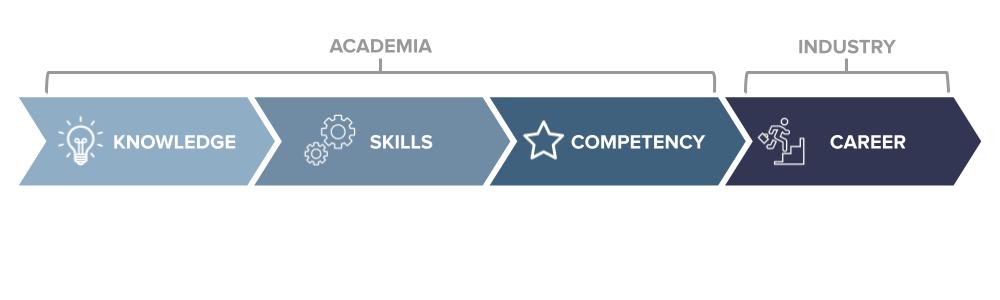

In the world of software engineering, we see positive benefits from the push to “shift security left.” DevOps have started to shift their purview to include security development within their programs, becoming DevSecOps as a result. This shift has resulted in increases in security quality, a more streamlined development process, and increased protection of products. Katie Haug, Marketing Director of KLogix, states that, “when processes are performed earlier in the development lifecycle, including security checks and audits, it becomes easier to find flaws and potential issues, and resources are used more efficiently” (Haug, 2020). Similar results are present when competency development comes before entering a cybersecurity entry-level career role. The process of shifting competency left also leads to a more resilient, “ready for work” cybersecurity workforce for industry, and ultimately more secure platforms.

When examining Figure 2, we can see a model of competency development that takes place within academia and takes pressure off of employers to spend time training employees in basic skills needed for their jobs. This creates a smoother transition into the workforce. Providing students with practical experience under the supervision of an accomplished professional prevents employers from investing nonessential time, money, and resources into training individuals that should already be ready for work. Gaining real-world experience before entering the workforce is key in producing a cyber-ready professional.

In order to shift competency left, cybersecurity students need the same mentoring, training, and growth opportunities afforded to students in other professional fields of study. The Institute for Pervasive Cybersecurity at Boise State University is shifting competency by producing ready for work cyber professionals that have real-world experience before graduating. We supply students with opportunities to monitor cyber threats and work with real clients across Idaho. Edward Vasko, the institute’s director and 30 year cybersecurity professional, explains higher education should support the “idea of taking competency development time that employers now take for granted and shift it left by giving our students real-world competency and real-world effectiveness by putting them in real-world situations. Just as the medical field uses rotations and residencies.” Students from across the state of Idaho have the opportunity to acquire competency-based training from projects like Boise State’s own Cyberdome that prioritize reducing risk within rural communities.

The Cyberdome is a collaborative hub for competency-based training to reduce risk of cyber attacks in communities around Idaho and produce a cybersecurity workforce in sync with Idaho’s business, technology, and government sectors. One ongoing project in the Cyberdome allows cyber analyst students the opportunity to investigate our client’s network traffic data for any evidence of malicious activity. All reports of such activity are sent to the active Cyberdome manager, who then alerts the affected party and devises a plan of action. This project allows students to work on real problems faced by our customers, thus strengthening the students’ practical knowledge and shifting competency left.

Sources:

Benson, A. (2021, October 6). The Cyberdome initiative. Institute for Pervasive Cybersecurity.Retrieved May 5, 2022, from https://www.boisestate.edu/cybersecurity/2021/10/06/the-cyberdome-initiative/

Haug Marketing Director, K. (2020, June 25). Shift left: The rise of devsecops. klogix.png.Retrieved May 5, 2022, from https://www.klogixsecurity.com/blog/shift-left-the-rise-of-devsecops