U.S.-Resident Learners of English

- Refugees from Iraq, Afghanistan, Congo, Rwanda, Somalia, Nepal, Bhutan, Iran, Bosnia, Ukraine, and other countries

- Immigrants from Mexico, Russia, Iran, Thailand, Japan, and other countries

- U.S.-born citizens who speak a language other than English at home

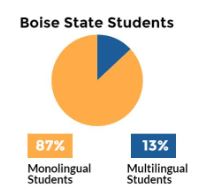

In Fall 2015, 1,254 first-year students at Boise State were surveyed about their language backgrounds. Of students who indicated that they were either U.S. born or arrived before the age of 18, 9% of U.S.-resident students say English is not their native language or they weren’t sure (bilingual, in most cases). Of the entire Boise State student population, including international students, approximately 13% are multilingual.

The insights and techniques provided on this site benefit a wide range of diverse students and offer benefits for all students. Additionally, you can contact the English Language Support Programs here to consult with us about how to become an inclusive teacher.

Understanding Linguistic Diversity

- Linguistic diversity (a diverse population of speakers who are proficient in a language other than English) adds value to higher education.

- Varieties of world Englishes are spoken globally. As students prepare to enter a globalized world, a variety of Englishes is currently and will continue to be prevalent.

- The acquisition of language is a lifelong learning process, thus, the goal of instruction should not be based on correction with the hopes of entirely assimilating the student’s language use.

- Avoid the “myth of transience” (Rose, 1985, qtd in Zamel 1995) which holds to the false notion that students’ language challenges are temporary. Instead, faculty can integrate language support into content learning in a successful way.

- Focus on areas where meaning is not conveyed clearly in students’ writing and work to help them be effective in the rhetorical context of academic communication.

Linguistic Flexibility

With an understanding of linguistic diversity, we can turn our attention to how this can inform our teaching practices. In the classroom, we can model and demonstrate linguistic flexibility. To demonstrate the mindset of linguistic flexibility consider the following:

- Having empathy for language learners;

- Valuing linguistic variation (dialects, accents, genres, disciplinary differences);

- Sharing responsibility for good communication (as readers, writers, speakers, and listeners):

- Being a patient listener and reader;

- Providing course content in multiple ways (visual, oral, written).

- Drawing on students’ various kinds of knowledge–including knowledge of other languages–and seeing it as a resource for all to learn from.

- Modeling clear communication;

- Guiding all students in facilitating good communication (especially in small groups);

- Helping with language development, not holding nonnative speakers to an unrealistic (and constantly changing) U.S.-based standard.

To see more ideas for demonstrating linguistic flexibility in your classroom, check out our Practical Ideas page.