Some classes lend themselves to online learning more easily than others. Studio art classes, many of which require specific tools and equipment, from soldering torches to printing presses, face particular challenges in this era of remote learning.

For some students and faculty, isolation because of COVID-19 has become an opportunity to brainstorm, to take a step away from machinery and become more self-reliant in the pursuit of art.

“I’ve always said that this field is about creative problem solving,” said Anika Smulovitz, a professor in the Department of Art, Design and Visual Studies who heads the art metals program. “Creating with recycled items and low-tech methods is not out of the realm of what metal artists do. It’s just not usually what we teach.”

The new circumstances already have meant more time for research projects, documentary viewing and even a virtual tour of Smulovitz’s home studio.

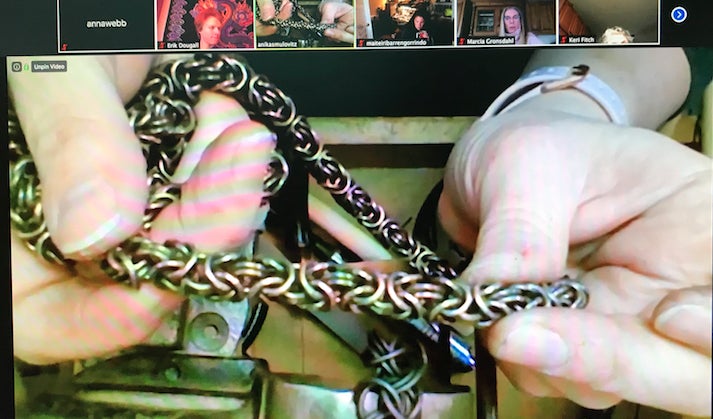

For the rest of the semester, students who would have been soldering and enameling metal are making Byzantine- and Viking-style chains from modest materials like rebar tie wire and thin copper. Among Smulovitz’s new assignments: the Zero Karat One-Week Wearable Challenge. Students are making adornments whose sophistication belies the fact that they’re made from materials like playing cards, shredded milk jugs and tile spacers.

Smulovitz thinks some students will be inspired to create work in response to this odd era – for instance, she’s invited students to involve their family members and fellow quarantiners in the Zero Karat Challenge. On another positive note: since all studio art professors across the country are facing similar obstacles, they’ve been meeting online to share ideas and brainstorm, she said.

For Maite Iribarren-Gorrindo, a visual arts major in metal arts and a student in Smulovitz’s advanced class, the idea of leaving behind the beloved metal studio in the new (and long-awaited) arts building was hard.

“I thought for sure our classes would suffer because they’re so hands-on,” she said. “I thought, how on earth can we translate everything to a computer screen?”

She credits Smulovitz with creating an online platform where students can show their work, share tips – like a heads’ up when the price of silver falls – and resources like they would in a traditional classroom. All the things that make class so valuable.

“We are still able to do that. It mimics the classroom experience,” said Iribarren-Gorrindo.

She’s among the fortunate students who have a home studio. Hers includes an old piano converted into a work bench and a soldering set-up in her garage. She has embraced the semester’s new low-tech direction, though. Since classes went online, she has taken advantage of the solitude of working at home and has even invented a new tool: a piece of slotted metal for making jump rings (the rings that make up a chain), that she might not have otherwise.

Hand building at home

Kelly Cox plans to teach ceramics this summer, but will be doing so remotely. She’s already come up with a plan: students will pick up kits from the Potter’s Center. Cox will teach clay hand-building methods online that students can do at home. The summer session, scheduled to start in July, will include research projects and sketchbook exercises focused on detailed surface designs and the development of forms. Critiques will take place online.

Though Cox worries about arts-based institutions in the Treasure Valley that operate on slim budgets in normal times, she sees an upside for students and creators in the Boise State community.

“Over the years I have worked in basements, bedrooms and garages,” said Cox. “This course is an opportunity for students to develop techniques and a body of work they’ll be able to expand on when they’re out of school and no longer have access to the perks of a full studio.”

Cox has volunteered her home kiln to fire student work. She also teaches ceramics at Fort Boise and plans to fire work there if social distancing rules are lifted. She welcomes the idea of students meeting off campus, showing work and sharing ideas in a more social setting like a home studio.

“Things could look different by July,” said Cox.

Printing without a press

Amy Nack teaches printmaking – a medium largely reliant on presses. One can make a print from a carved linoleum block by rubbing it with a wooden spoon instead of sending it through a press, “but it’s not the same,” said Nack, “and it’s not a lot of fun.” Other methods, like drypoint, in which artists scratch images into a plate, ink the plate and run it through a press, absolutely require a press. Drypoint is out for now.

Luckily, Nack, who owns Boise’s Wingtip Press, has a stash of supplies in storage. She made kits for each of her 30 students including paper, inks, a gel printing plate and more. She’s cognizant that students have already paid a lab fee and doesn’t want to ask them to pay more. So, like Smulovitz, she’s brainstormed ways students can use easily found materials.

“We may do something as simple as think of an every day object, like a fork, then use the gel plate to take impressions off that item, to really focus on that object, think of who made it, how important it is, and ask whether we will still use it in 100 years,” said Nack.

As a printer with a strong affiliation for public art, Nack has often worked outside traditional print shops. She ran a workshop for the City of Boise in which artists made prints on-site at the Old Idaho Penitentiary with ink and rollers. She’s run workshops in public libraries and even on the banks of the Boise River where participants made print blocks out of old flip-flops. She’s made giant prints using a steamroller to print on bedsheets.

“I’ve always had to figure a way to work without a press. It seems I have a jump start on that,” she said.

This semester will be an opportunity to be resourceful – to explore mixed-media projects, mail art, or projects with a winsome sensibility.

“There’s a lesson online that uses two potatoes,” said Nack. “You use one to carve a stamp to print. You use the other to make mashed potatoes. It’s light-hearted and you can have fun with it.”

Nack heard from some students who felt that they’d lost their community by going online. Lahn Russell, a senior graphic design major, said she struggled with the abrupt end of the semester. She and her fellow graphic designers have lamented that they didn’t get to experience all the “last ofs” together in person – the last class, the last project, the last critique.

“We didn’t get to say our goodbyes,” said Russell.

She and her design peers are brainstorming ways to share their work and reaffirm their identity as a class. They’re designing “care packages,” collections of work samples, stickers, zines, toy rats (rats are the program’s unofficial mascot) and more.

“I think we’re going to be sending out these packages to people who have inspired us or people we look up to. Ideas are still flowing,” said Russell.

Creative pursuits can be a balm for difficult times, said Nack. “Art is a good diversion because you’re in the moment, not rewriting history, not making the future. And in 50 years you can tell people you made it in lockdown.”

– Story by Anna Webb