The Identity, Culture, and Languages category welcomes submissions that focus on exploring elements of identity, culture, or languages, through the written word. This category seeks writing that investigates the human experience, particularly through perspectives that are frequently marginalized or excluded, which may include members of the LGBT+ community, people with disabilities, non-citizens, and multilingual writers. Submissions are open to projects written in any course, at any level. There are no length limits for this category. Nicole Kreiner wrote the 2nd place submission in the Identity, Cultures, and Languages category for the 2022 President’s Writing Awards.

About Nicole

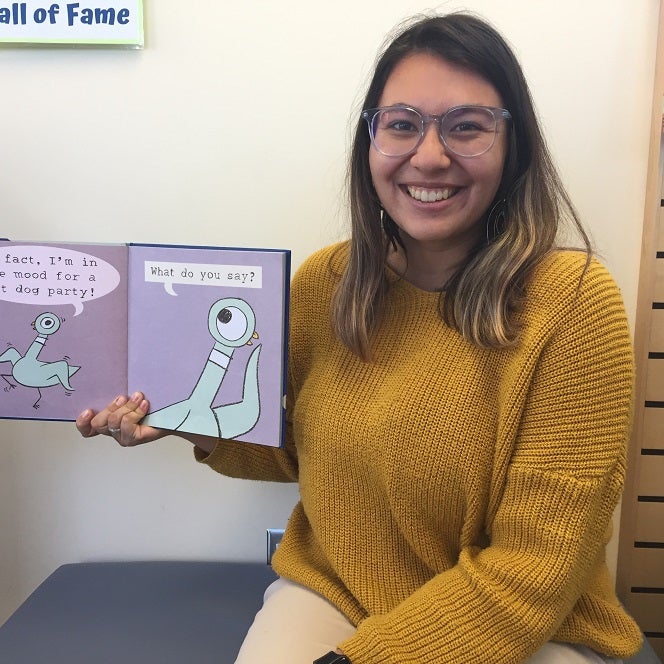

I’m a 22-year-old English Major with an emphasis on Writing, Rhetoric and Technical Communication. I’ll be graduating next Spring with my Bachelor’s and will then pursue my Masters in Library and Information Science. I plan on becoming a children’s librarian and have a heavy focus on ethnicity and race in children’s literature since it was so lacking in my own books growing up. I currently work at the Meridian Library District in the Youth Services Department.

Winning Submission – On Growing Up (Brown)

I’m seven or twelve or nine. It’s a summer afternoon, much like countless we’ve had before, and I’m in the backyard, my feet on the prickly brown grass where we’ve set up the sprinkler — entertainment and watering the lawn, two birds one stone.

It’s me, long dark hair swinging down the one piece suit, as we squeal and run through the water. My sister and brother dare me and each other to do various acrobatic feats — cartwheel, no now do a somersault, no do a cartwheel and then a somersault — as we bore of simply running through the water. When we get too cold, we lie in the hot sun and my brown skin gets darker as the water dries off. We chase each other through the dry grass, avoiding the prickly weeds because we’ve learned the lesson of stepping on them with bare feet — pokey pokeys we call them.

Soon we drag the trampoline over the sprinkler and it’s our personal water park. We giggle, the three of us, so close in age that many of my friends later tell me that when we first met, they thought we were triplets. We’re not — I’m the oldest, Chris is the middle, and Jessi’s the baby. But we move and act in the same way — my sister’s hair as long and dark as mine, my brother and Jess both with curly locks and dimpled smiles. We all are dark, but I’ve always been the darkest, always the first to turn the deep dark brown that makes us the envy of our sun-burned friends. We climb trees and sing to each other across the yard. Our hair is wild and tangled and wind-blown, our feet brown and bare, our skin sun-kissed.

We are animals and isn’t that sad?

I think of this scene — a repeated scene of my childhood summers — when I think of my childhood living room. My favorite spot was the couch by the window, where I could see the lawn where we played. I would sit there and read for hours and hours because I could look at the lawn every twenty minutes or so and let my eyes rest (Dad’s orders). Here is where I read to myself for the first time, here is where I would look up and see the dry spots in the lawn where I and my siblings would set up the sprinkler later, here is where I sat and watched the cherry tree’s blossoms fly away on the breeze.

Maybe it was here where I first read of a brown-skinned person. It was in Anne of Green Gables, a scene where Anne helps a poor dark child who holds her pale white hand with their own “brown paw”. I’ve never forgotten that phrase. It echoes every time I look at my own dark hands. It taints every memory I hold close of me and my siblings, because while I look back and see joy joy joy, I can’t help but think that Anne, my beloved Anne, and so many of my other literary heroes, would look and only see animals. Anne, who I loved so much because she was so like me, who loved reading and nature and poetry, who got lost in imaginative fantasies, who was as white as I was brown. I never thought there was a difference until she drew a line in the sand — you are unlike me, you with the dark skin, you with the slow speech, you with the paws.

I am not an animal — right? I was a child, but the darkest girl in all of my classes. My three best friends were blonde and blue or green eyed. It was like a game; one of these things is not like the other; one of these things is brown. Is it any wonder that my favorite princess was Sleeping Beauty who had the long mane of sunshine that I so desperately craved?

My hair was long and straight and dark, cut like my mother’s in the pictures I’ve seen of her when she used to live in Mexico. I looked exactly like her — dark skin, almond eyes, and straight brown hair. But my literary heroes were Nancy Drew, Cam Jensen, Matilda, Anne of Green Gables, Laura Ingalls Wilder — white girls who might’ve shared my hair and eye color, but they weren’t dark. They helped the poor dark child, the wild dark child, the dark child with the poor parents and the different speech patterns. That is, if dark children were even mentioned at all. There were never dark adults or peers.

Race always existed at the peripheries of my childhood, the monster behind the corner, the tension in every opening scene of a horror movie. Race had rules I didn’t understand and I was thrown into the game with no playbook. No one wanted to broach the elephant in the room so they let it stampede all over me. Like that time when I was seven (or six or eight) when mom yelled at me. The family down the street (who used to babysit us three kids back when my mom went to class and dad went to work) had come up in my memories and I was talking with my mom about them, trying to remember their names. I told my mom, “You know, the family that took care of us! Their eyes go like this —” and here I pulled the corners of my eyes to emulate the family’s Asian eyes.

“Nicole!” — I was never Nicole unless I was in trouble — “Don’t do that! They would not like it if you did that.”

Why not, I wondered, as I played in the backyard. That’s what their eyes looked like.

Or that time when I was ten or nine or eleven. I was already learning that being smart meant reading classics, but I never really considered why the classics were so good — or why they were written by white dead people and why I should care about those opinions. If you read classics, you were smart, at least that’s what the contemporary novels I read seemed to say and my teachers and adults around me seemed so impressed when I read those old books, so I read them and received them as presents. I had read The Adventures of Tom Sawyer (a Christmas gift from my parents) and was talking about it with my family — and not just my immediate family, but my uncles and grandparents from my dad’s side. I don’t even remember how or why, but I said the n-word and I can remember the reaction to that.

“Nicole!” — at least five different adults yelled at once. “DON’T EVER use that word.”

I sat back, as if I was burned, and shut my mouth. At this point, I had never read a word I couldn’t use before. All my life I had used big words from books and had been praised for my “big vocabulary”. I had learned words from context and couldn’t explain them to my younger siblings because I’d never read a formal definition; I would try to define a word by a feeling. Now I couldn’t explain why I couldn’t use a word that Tom had used so effortlessly. No one told me that it was a slur. No one told me why a word can be used by a book that can’t be used by me. No one defined “slur” for me and I was scrambling for a context to understand this new word.

Or that time when I was twelve (or fourteen or thirteen) and I saw a black man for the first time in my life. I met him at my church; he was visiting and my grandfather (the pastor) introduced me to him. He was a darker black man than I had seen in movies or pictures and it’s always different to encounter someone in the flesh rather than in a movie. I shook his hand, now conscious of the concept of racism and of the fact that I shouldn’t be (racist that is), but really the thought that hammered through me was will his hand feel different than mine? I was so ashamed to think it, but still so desperately curious.

Is it any wonder that I was left to marinate in unallowed questions? By the age of two, children are able to recognize social characteristics, such as race and ethnicity (Serano-Villar and Calsada 22), and though I could recognize my mother’s colorful native tongue and my abuelita’s music, though I could tell you what racism was and what different races were, I still burned inside with unanswered questions. Why does Tom use words that I can’t use? What does a hand that looks like a night sky feel like? Why am I not allowed to ask?

Children can do more than just recognize race and ethnicity; They can also recognize when a person looks like them or not like them, whether that person speaks their language, or their mother’s language, or a foreign language. They can recognize ethnic traditions — things like songs and celebrations. They can see it in books and in movies. Yet, it wasn’t until I was twenty that I found the birthday song my abuelita and abuelito would sing to me in literature. Here I am, small and alone, sitting on the arm of my orange couch in my tiny apartment, a new adult still floundering and floundering along with the world as a virus holds us captive in our homes, and I’m crying. Bri, my roommate, is concerned, asking “What’s wrong?” because I’m just sitting and crying and this is not a common occurrence.

“It’s this book” I say, looking with watery eyes to the book with the Spanish and English title, about a boy living on the border who speaks my mother’s tongue and travels the line between the

U.S. and Mexico literally far better than I ever have figuratively. “It’s the first time I’ve ever seen this song in a story. It’s a song that my mom’s family sings when we do piñatas.”

They wait and I sniffle, trying to stop crying because I hate it, but I’m away from my family in a forced way and yet here they are in a place that I have never seen them before. I’m old enough now, have studied enough, have learned of book awards that have been created to address diversity gaps, have learned that the books I’ve read are mostly white and that I am mostly not. And yet.

“I’ve never seen this song in a book before. It’s…beautiful.”

When I was eighteen, before I read a book that made me cry, I finally allowed myself to be called Hispanic. College was coming and if I was Hispanic, I might get more scholarships, especially as a girl. Then my library participated in the Public Library Association’s Inclusive Internship Initiative, a nationwide program that sought to diversify libraries by showing diverse youth the possibility of public libraries. I applied for the job, got it, and proceeded to learn more about myself in a single month than I had allowed myself for the past 18 years. For the first time, I was around people who looked like me and who had stories like me, who asked each other “If it’s alright, can I ask what your heritage is?”

I’d never considered it might not be alright, never been asked my family’s history. It was always assumed — Hawaiian,, Alaskan Native, Indian. I thrived and because of the connection from the program, at age 19, I attended the American Library Association’s Annual Conference and was able to go to the Pura Belpré Celebracion, an annual award that honors Latino/a writers and illustrators. As part of the award celebration, several young girls — probably ranging from nine to twelve — danced ballet folklorico for us. As I left — rushing to another session— I stopped for a moment and watched these girls look at a giant poster of books that had won the award in the years past. These girls — hair still adorned in the traditional ribbons and braids — were pointing at the books, bragging, saying, “I’ve read this one and this one and this one!”

I ached with jealousy and joy and anger, because, while I’m so happy that they got this experience, why didn’t I? Didn’t I deserve to take for granted books that had brown girls and boys? Why do I still nurse wounds from books, hating my hands and hesitating everytime I say that I’m Latina?

Currently, I still work at a library and go to school. I want to get my masters in library science and become a children’s librarian, helping the children that look like me have a different experience forming their own racial/ethnic identities. Above my work desk, hangs a poster saying “We Need Diverse Books”, yet, according to a 2018 study, only 5% of recent children’s books feature Latinx children (“An Updated Look at Diversity in Children’s Books”) — and that’s actually more than a study conducted in 2014 when the number was 2.4%. That number is shocking compared to the 50% of books that feature white children or the 25% of books that feature non—human protagonists. That leaves only 25% of books for the minority children — black children, Asian Pacific children, Indigenous children, and LatinX children. And, I’m sad to say, that’s progress. How am I supposed to help children develop identities when I’m given only scraps of books — books that teach them they have to struggle for justice and recognition or that they only matter in history, while white children get to go on adventures in fantasy lands or get to become doctors and astronauts?

I was robbed of my identity and my memories and lessons about empathy. Books taught me, not about other people, but about other white people. They taught me racial slurs, they taught me that children like me are animalistic, and that I had no place in literature unless I was white.

I never called myself Hispanic or Mexican until I was in my last year of high school and to this day, I struggle calling myself Latina. I couldn’t be those terms, because people who are those terms are poor and dark and they aren’t important, right, Anne?

I’m helping a woman check out a book and she starts raving about The Hate U Give, a contemporary novel about a black girl who witnesses her friend being murdered by police. It’s one of my favorite books by one of my favorite authors and I’m excited to talk about this book. The woman is too and talks about the horrible racism in this book. “I would never say something like that though,” she declares. “I’m color blind.”

I disappear.

Works Cited

- “An Updated Look at Diversity in Children’s Books.” School Library Journal, School Library Journal, 2019, www.slj.com/?detailStory=an-updated-look-at-diversity-in-childrens- books.

- Serrano-Villar, M., & Calzada, E. J. (2016). Ethnic identity: Evidence of protective effects for young, Latino children. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 42, 21–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2015.11.002