Submissions in the research category are open to research topics in any field: STEM, Social Sciences, Business, Humanities, etc. Submissions should use the documentation style appropriate to the discipline and should not exceed 20 pages. Victoria Northrop wrote the 1st place submission in the Research category for the 2022 President’s Writing Awards.

About Victoria

My name is Victoria, and I’m currently a Junior majoring in English with a specialization in WRTC (Writing, Rhetoric, and Technical Communications). Since I was eight, I’ve lived in Boise and have been lucky enough to attend BSU for the past two years. I’ve always had a passion for media and, more recently, the intersection between media, politics, and culture in our world. When attending CU Boulder my freshman year, I previously majored in Media Studies and have maintained my passion for studying this topic throughout my academic journey. In my free time, I enjoy running, reading, and trying to keep my Duolingo streak. I am so honored to have my writing featured among so many other talented students from BSU.

Winning Submission – Tiktok’s Transphobia: The Swift Radicalization of Casual Behaviors

In the early days of YouTube, a phenomenon known as “falling down the rabbit hole” was a commonplace occurrence. For one parent, their son was lured to the alt-right after white supremacists on Reddit and YouTube provided him with a platform to air his grievances and be treated as “an adult” (Anonymous, 2019). However, in recent years YouTube has cracked down on radicalization pipelines created through their platform’s recommendation algorithm and eliminated a large majority of the alt-right content from their platform. And while the situation on YouTube has improved since the 2016 election cycle, this type of radicalization through algorithms didn’t go away; it merely migrated.

TikTok is a video-sharing app specializing in short-form content that lasts from 15 seconds to 3 minutes. TikTok is most well-known for its algorithm’s accuracy at serving viewers the exact kind of video content they’ll want to see, content that will keep users on the platform for as long as possible. TikTok describes the algorithm’s process as ” ranking videos based on a combination of factors — starting from interests you express as a new user and adjusting for things you indicate you’re not interested in, too” (Worb, 2022). According to LaterBlog, a site dedicated to helping users grow on different social media platforms, the subject matter of a video is one of the main factors influencing a video’s reception by the algorithm (Worb, 2022). Since TikTok’s algorithm generates recommendations based on preferences and interests, the subject matter of a TikTok can help create group identities and subcultures within TikTok’s ecosystem.

As a growing media juggernaut with roughly 1 billion active users every month, the attention economy on TikTok is highly competitive, and the algorithm boosts creators who cater to the short attention span that this influx in content creates.

Although now heavily moderated on YouTube’s platform, the radicalization of vulnerable people has been revitalized through TikTok thanks to the personalized nature of its “For You” page algorithm. The revitalization of right-winged radicalization through social media platforms was re-discovered by two researchers for Media Matters. To examine the extent of this radicalization on a user’s “For You” page, Media Matters created an experimental account that solely interacted with transphobic content and videos. The result was a slow escalation in increasingly transphobic content and the eventual recommendation of derogatory content towards other protected groups (women, racial minorities, etc.).

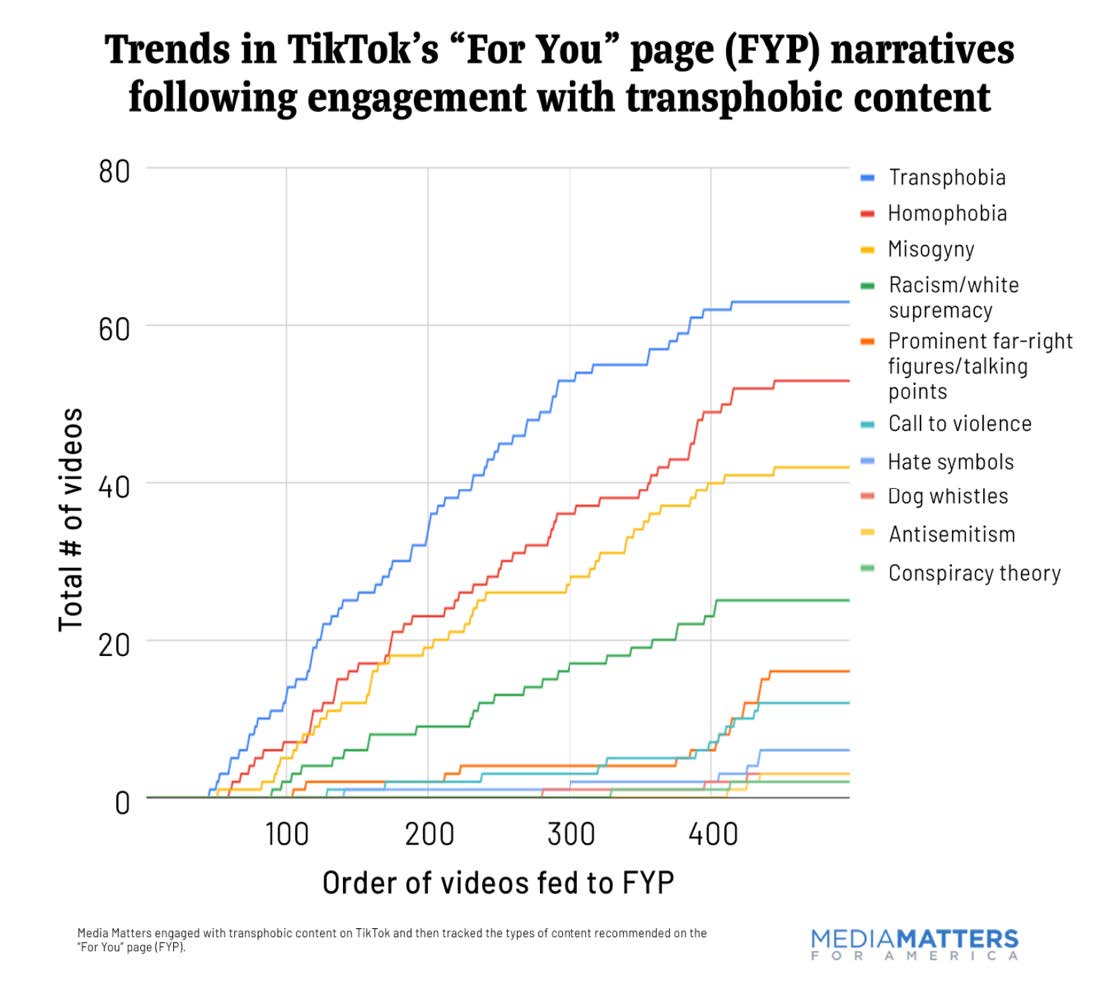

One of the two primary researchers on the Media Matters study, Abbie Richards, created a TikTok that goes over the contents of her co-authored study. In her TikTok, she lays out the initial research question that prompted this study, “we wanted to examine whether or not transphobia is a gateway prejudice that leads to … far-right radicalization” (@tofology, 2021). More specifically, the researchers wanted to gauge whether interaction with transphobic content on TikTok would be enough for the algorithm to radicalize users. The graph below details the 300+ pieces of content recommended to Abbie on the test account by the algorithm. The sharp spike in calls to violence and antisemitism in the latter half of their recommended content is especially noteworthy. These findings by the Media Matters study sit in direct opposition to TikTok’s public statements that “There is absolutely no place for violent extremism or hate speech on TikTok, and we work aggressively to remove any such content and ban individuals that violate our Community Guidelines” (Swan & Scott, 2022). Although the findings by Media Matters display alarming statistical evidence, it’s necessary to question the methodology of their results; specifically, what did the researchers count as a transphobic or a misogynistic video?

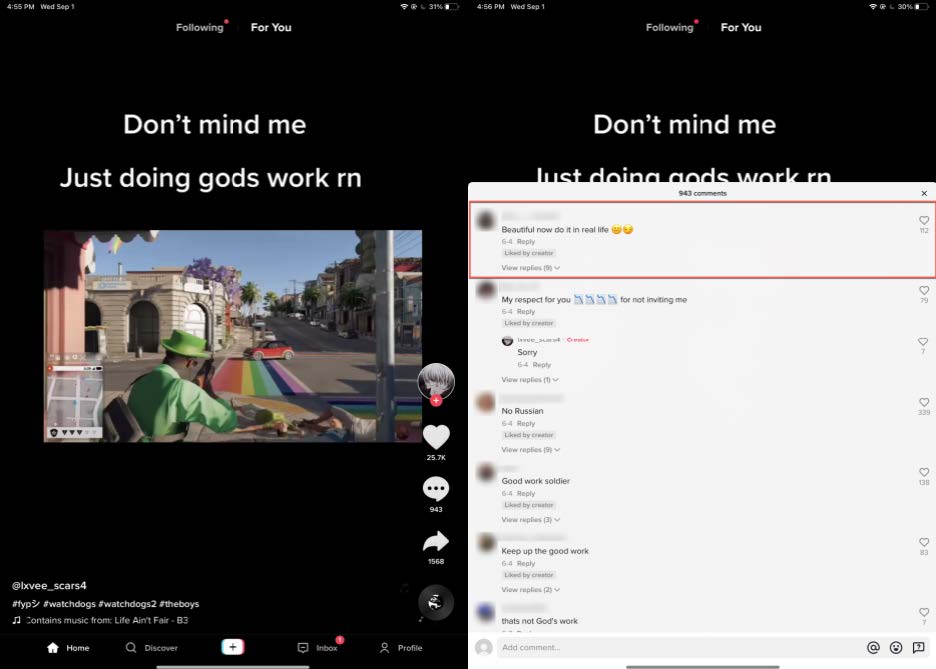

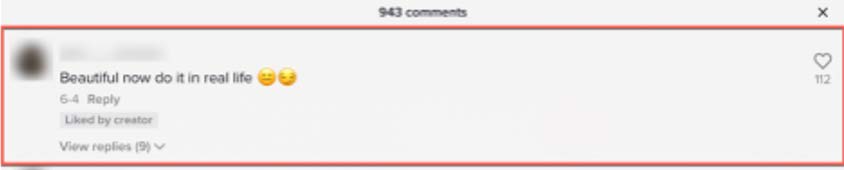

The screen captures below are from a video served to the Media Matters account by the TikTok algorithm. Little and Richards logged this video under homophobia and calls to violence. In the video, a player is directing their videogame avatar to shoot and kill NPCs at an in-game gay pride celebration (Little & Richards, 2021). This video received over 200,000 views and is a prime example of how quickly the content recommended by TikTok can escalate to the encouragement of violent hate crimes (Little & Richards, 2021). More alarming is the accumulation of over 20,000 likes, meaning that 10% of the users that TikTok recommended this video for chose to actively engage with the content, signaling to the algorithm that it had served them desired content. By creating a safe environment for toxic discourse, users passively and actively encourage one another to make derogatory comments, such as the top comment on this video, which states, “Beautiful now do it in real life” (Little & Richards, 2021).

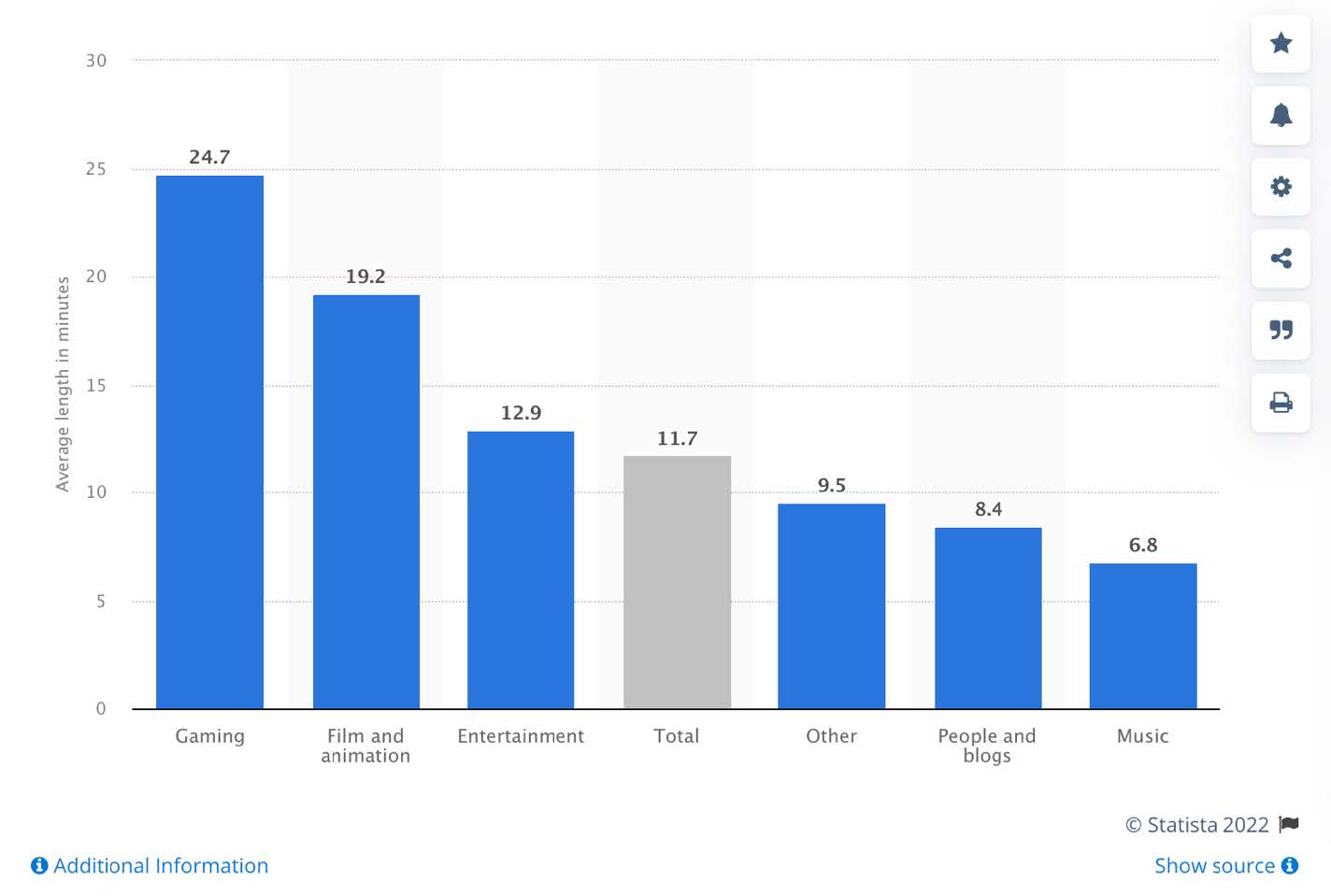

Although radicalization on TikTok follows a similar pattern to the radicalization seen on YouTube’s platform, the speed at which radicalization can occur has increased 10-fold. Compare the average length of videos on each platform, and the full impact of this assertion is clear. According to Statista, a German company that specializes in user data, the average YouTube video length, across all categories, in 2018 was roughly 11 minutes (Ceci, 2021). Compare that to more recent data collected on TikTok, which details that the average video length from Jan-August of 2021 was 47 seconds (Hammond, 2021).

Compare this data to the roughly 400 videos Media Matters encountered through their test account. The account began receiving transphobic content within the first 100 videos recommended by the algorithm (Little & Richards, 2021). This data means that it would take a little over an hour before an account interacting with transphobic content to received alt-right ideologies on their “For You” Page. In contrast, it would take roughly 18 hours to experience the same phenomenon on a YouTube account. Co-author Abbie Richards sums up these findings in her previously mentioned TikTok on the study, “So a user could feasibly download the app at breakfast and be fed overtly white supremacist, neo-Nazi content before lunch” (Richards, 2021).

“So, a user could feasibly download the app at breakfast and be fed overtly white

supremacist, neo-Nazi content before lunch.”

Abbie Richards, @tofology 2021

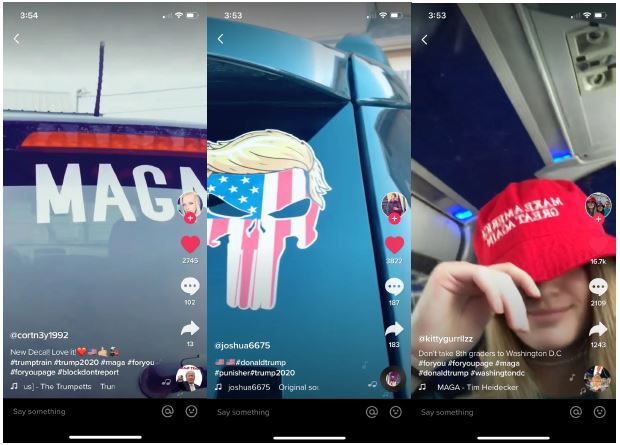

Again, it’s important to stress the role interests and community play in a user’s experience on TikTok. The algorithm’s primary function is to determine users’ interests and provide them with content that caters to those interests or niches. In doing this, the algorithm creates a platform rife with filter bubbles or the ideological isolation of groups based on algorithmic selectivity (Technopedia, 2018). Nowhere is this algorithmic phenomenon clearer than on “TrumpTok,” an online community of right-winged Trump supporters who use TikTok to collectivize. This community is a primary example of the dangers algorithmic radicalization pose. Now released reports from The Department of Homeland Security have revealed how members utilized the platform to organize for the January 6th insurrection (Swan & Scott, 2021). Before January 6th, radicalization, and organization of far-right groups through TikTok flew under the radar of most intelligence agencies since social media sites like Facebook and YouTube were long thought by the intelligence community to be the primary locations for the organization of extremist groups (Swan & Scott, 2021).

Additionally, organizers on TikTok are using many of the strategies previously employed by alt-right groups on YouTube and Reddit. Most notably, the groups rely on symbols and cultural signifiers to convey discrete messages to their audiences while avoiding the detection of moderation systems (Mamié et al., 2021). As seen below, the punisher logo or MAGA hat are visual signals of membership within a group. These are more harmless examples but speak to the evidence in the Media Matters study where the use of Nazi and white supremacist imagery discretely signaled membership to their viewers.

So how does online membership in “TrumpTok” relate or funnel into radicalization into the alt-right on TikTok? The hyper fixation of the Republican party on Trans issues and Trans rights, particularly as it relates to sports and public amenities, has led to an increase in casual transphobic rhetoric and sentiment in many right-winged conservatives. Specifically, the purposeful misgendering of trans athletes by former Republican President Donald Trump (Massie, 2021). More recently, Trump purposefully espoused casual transphobia at CPAC. This rhetoric is a prime example of the casual transphobia endorsed by the Republican party. The inevitable consequence of this casual transphobic rhetoric is an escalation in radicalization on TikTok, radicalization that the algorithm transforms into alt-right radicalization in merely an hour of engagement.

“There is absolutely no place for violent extremism or hate

speech on TikTok, and we work aggressively to remove any such content and ban individuals that violate our Community Guidelines.”

Jamie Favazza, TikTok spokesperson 2021

Not only is this radicalization set to occur at a rapid pace due to the current political climate and power of the algorithm, but TikTok themselves are unwilling to address these issues in any meaningful capacity. In a follow-up article to the Media Matters study, TikTok told Insider that the company took down all the videos featured in the study (Keith, 2021). In the company’s transparency report for 2021, a spokesperson stated that TikTok would “maintain a safe and supportive environment for our community, and teens in particular, we work every day to learn, adapt, and strengthen our policies and practices” (Keith, 2021). While strict enforcement of these values has yet to occur in any meaningful capacity, the historical precedent set by other social media giants leaves little to be desired. For example, following a whistle blower’s allegation of Facebook’s first-hand knowledge and dismissal of the platform’s radicalization capabilities, the platform rebranded into the newly named “META” (Zadrony, 2021).

“I’m here today because I believe Facebook’s products harm children, stoke division, and weaken our democracy.”

Frances Haugen, Facebook whistleblower 2021

Regarding TikTok’s infestation of radicalization, it’s crucial to acknowledge the timeline of events to better grasp the ongoing prevalence of radicalization on the platform. TikTok’s radicalization issues originally came to light after public scrutiny following the January 6th insurrection in early 2021. Nearly ten months after the public statements by TikTok that they would amend the problem, Media Matters released their study, demonstrating that the platform’s algorithm was still rife with radicalization bias. Either TikTok is unwilling to invest in the exhaustive moderation necessary to combat these groups, or they are aware, like Facebook, that engagement by these groups contributes to a large enough percentage of their users that maintaining them is fiscally beneficial (Zadrony, 2021).

Not understanding or addressing the origins of “casual transphobia” will allow for the radicalization pipelines on TikTok to continue thriving. A medium that has recently come under fire for stirring casual anti-trans sentiment is comedy. Unlike the controversial comments and characters created by once-beloved author J.K. Rowling, comedy, and comics themselves are challenging to critique since criticisms often fall on the deaf ears of loyal fans (Haynes, 2020). When casual viewers and fans alike critique a comic for their messages, the comics easily dismiss their objections as “not being able to take a joke.” This tension between comedy and casual transphobia reached a boiling point in 2021. Dave Chappelle’s 2021 special, “The Closer,” presents a dangerous precedent from which casual transphobia can flourish. Although sincere at times, particularly when Chappelle discusses his relationship with the late trans comic, Daphne Dorman, his sincerity is challenging for many in the LGBTQ+ community to trust when it’s abutted with trans slurs and pledged loyalty to “team TERF” (Trans Exclusionary Radical Feminists) (Jenkins, 2021). Even more obstructive is Chappelle’s pitting of black and LGBTQ+ interests against one another, ignoring the intersectionality and roles of Black LGBTQ+ people. Much like comedy, TikTok has a societal connotation of being harmless fun, a place where viral dances and soundbites dominate. However, this misconception of harmlessness allows destructive behavior and language to permeate beneath the surface.

“In our country you can shoot and kill a [black person], But you better not hurt a gay person’s feelings.”

McDermott, American Magazine, Dave Chappelle, Netflix, “The Closer” 2021

TikTok has a radicalization problem, a problem fueled through casual transphobic rhetoric encouraged in both entertainment media and political ideologies. The on-ramp from transphobia to alt-right radicalization, as illustrated in the Media Matters study, demonstrates an alarming problem that continues to go virtually unsolved (Little & Richards, 2021). “Other social media companies have struggled with their platforms radicalizing users into the far right, but TikTok’s rapid supply of content appears to allow exposure to even more hateful content in a fraction of the time it takes to see such content on YouTube” (Little & Richards, 2021). Although the study from Media Matters doesn’t call for additional investment or investigation, it’s clear that this small-scale study has uncovered a concerning pattern that ought to be challenged and investigated more thoroughly at a larger scale across numerous test accounts. Additional investment and publication of work studying the nature of the algorithm could help bring to light not only the culture around transphobia on the app but uncover what other ideologies and beliefs similarly act as “gateways” into the alt-right in the eyes of the algorithm. Whether or not TikTok is willing to invest the funds to adequately combat this issue has yet to be seen. However, what’s clear is that the radicalization once prevalent on YouTube and Reddit has found a new home on TikTok, a home where the formation of harmful ideologies can solidify in mere hours.

References

- Anonymous. (2019, May 5). What Happened After My 13-Year-Old Son Joined the Alt-Right. Washingtonian. Retrieved March 31, 2022, from https://www.washingtonian.com/2019/05/05/what-happened-after-my-13-year-old-son joined-the-alt-right/#The-Crime-

- Ceci, L. (2021, August 23). Average YouTube video length as of December 2018, by category. Statista. Retrieved March 9, 2022, from https://www.statista.com/statistics/1026923/youtube-video-category-average-length/

- Hammond, M. (2021, September 30). 4 Insights You Need To Know About Video Length On Social Media. ListenFirst. Retrieved March 9, 2022, from https://www.listenfirstmedia.com/4-insights-you-need-to-know-about-video-length-on social-media/

- Haynes, S. (2020, September 15). ‘More Fuel to the Fire.’ Trans and Non-Binary Authors Respond to Controversy Over J.K. Rowling’s New Novel. TIME. Retrieved March 9, 2022, from https://time.com/5888999/jk-rowling-troubled-blood-transphobia-authors/

- Keith, M. (2021, December 12). From transphobia to Ted Kaczynski: How TikTok’s algorithm enables far-right self-radicalization. INSIDER. Retrieved March 9, 2022, from https://www.businessinsider.com/transphobia-ted-kaczynski-tiktok-algorithm-right-wing self-radicalization-2021-11

- Little, O., & Richards, A. (2021, October 5). TikTok’s algorithm leads users from transphobic

videos to far-right rabbit holes. Media Matters for America. Retrieved February 4, 2022, from https://www.mediamatters.org/tiktok/tiktoks-algorithm-leads-users-transphobic videos-far-right-rabbit-holes - Mamié, R., Ribeiro, M. H., & West, R. (2021, May 12). Are Anti-Feminist Communities Gateways to the Far Right? Evidence from Reddit and YouTube. WebSci’21. https://arxiv.org/pdf/2102.12837.pdf (Links to an external site.)

- Massie, G. (2021, February 28). Trump mocks transgender athletes in first speech since leaving office. INDEPENDENT. Retrieved March 16, 2022, from https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/americas/us-politics/trump-transgender athletes-cpac-speech-b1808917.html

- McDermott, J. (2021, October 25). Dave Chappelle’s ‘The Closer’: Empathy, Humility and the Lack Thereof. America Magazine. Retrieved March 9, 2022, from https://www.americamagazine.org/arts-culture/2021/10/25/dave-chappelle-closer transgender-241712

- Swan, B. W., & Scott, M. (2021, September 16). DHS: Extremists used TikTok to promote Jan. 6 violence. POLITICO. Retrieved February 4, 2022, from https://www.politico.com/news/2021/09/16/dhs-tiktok-extremism-512079

- Technopedia. (2018, May 17). Filter Bubble. Technopedia. Retrieved March 9, 2022, from https://www.techopedia.com/definition/28556/filter-bubble

- Worb, J. (2022, January 14). How Does The TikTok Algorithm Work? Here’s Everything You Need To Know. Later Blog. Retrieved February 16, 2022, from https://later.com/blog/tiktok-algorithm/

- Zadrozny, B. (2022, October 22). ‘Carol’s Journey’: What Facebook knew about how it radicalized users. NBC News. Retrieved February 4, 2022, from https://www.nbcnews.com/tech/tech-news/facebook-knew-radicalized-users-rcna3581