Any student enrolled in English 101P, 101, 102, or 112 during Spring 2022 through Spring 2023 may submit an essay of any kind on any topic. There are no length limits for this category. Lauren Sichenze wrote the 1st place submission in the First-Year Writing category for the 2023 President’s Writing Awards

About Lauren

Lauren Sichenze is an Idaho native, with a dash of East Coast, who is pursuing a degree in Interdisciplinary Professional Studies with a Creative Writing minor at Boise State University. Upon graduating, Lauren plans to enter into the publishing industry and later continue her education with a Master’s in Creative Writing. In the future, she hopes to publish more of her work. Apart from writing, Lauren enjoys practicing martial arts, reading, and spending time with her cat.

Winning Manuscript – Beyond the Blackbelt: The Path to Mastery

The ancient tradition of Martial Arts goes beyond that of combat, and the few individuals who dedicate decades to the practice achieve much more than mere fighting prowess. Their mastery cannot be measured by belts or forms, but instead culminates in profound self-cultivation.

Practice Makes Perfect.

We’ve all heard the saying. When you see an expert at their craft often the answer to their ability isn’t simply talent, but practice. So when a Master of martial arts steps onto the floor, every move you see has been practiced hundreds of thousands of times. Each motion is considered and refined. Yet a trained eye will know it’s still not perfect. This then begs the question, if perfection isn’t the road to attain mastery, then what is? It’s only as the journey of traditional martial arts carries you forward in your practice, that you begin to grasp what mastery means.

A kick at the waist, snapping out and back, turns into a kick at the chest, turns into a kick at the head. One, two, three, over and over again. Form after form, sweat dripping down your forehead, hands on your hips as you breathe heavily trying to catch your breath before you start all over again. In my first few years of martial arts, perfection was my aim. The truth only dawned on me later that the word “art” in martial arts plays a much bigger role, and the moment that it did, the meaning and the purpose of advancement changed in my mind.

Picture this, a blistering hot day, the sun glaring down at you from a cloudless sky, surrounded by a park packed with friends, family, and strangers, and a long row of senior black belts staring down at you from the top of a small incline. This was my test into 2nd degree black belt. The feeling, a turbulent mix of terror and excitement, could only be described as an intense buzzing somewhere in the region of my chest. For non-practitioners it’s important to note that a black belt test is meant to challenge you physically, mentally, and emotionally. Mistakes are inevitable under the pressure, if you don’t feel like puking you didn’t give it your all, and your ten forms should be crisp, detailed, and precise. For me this test was different, though. I was debuting a form not normally on the 1st to 2nd degree black belt roster; a double chisel form that I’d been practicing since I was a white belt.

Time passes in a blur when you’re testing, and after a few initial forms I was instructed to grab my chisels and line up in the front of the group, the spot that nobody wanted. Why? Because standing there meant standing directly in front of the Grandmaster, a man who has been practicing Shaolin Kung Fu for over seventy years. His stoic look made anxiety squirm in my stomach but I clutched my chisels tightly, bowed, and began. It wasn’t long before I reached the climax of the form, throwing one of my chisels so that it stuck into the ground before cartwheeling over to pick it up. I threw it with practiced aim and it stuck perfectly making my heart leap in my chest. Without hesitation I went into the cartwheel…and missed, overshooting my mark by a foot. You’d think this was a sad ending to my story, but no, because I laughed. In that moment I knew my passion and dedication mattered more than my unfortunate miscalculation. Perfection wasn’t the point. The black belt panel didn’t reprimand me for my mistake, they complemented my test as a whole because forms done perfectly but without any kind of real energy or personality are inferior to ones that are done with exactly those things plus a few mistakes along the way. This is the artistry in martial arts. This is what the journey of self cultivation looks like. This is what, with dedication and humility, can lead to mastery, because the title of Master doesn’t depend on mere physicality or skill in combat. Martial arts may be a business but it’s also a way of life rooted in history, tradition, and culture. Ultimately mastery is attained through an arduous journey with years of practice turning into years of knowledge and skill which then morphs into an ever evolving ability to not simply do a form, but to interpret it in a uniquely personal way.

What did you want to be when you grew up?

Five years old and you pick up the tiara and put it on your head beaming, or grab the stethoscope and check the imaginary heartbeat of every stuffed animal. We all had big dreams as kids, sporting costumes as we proudly walk down the street or hiding under the covers, flashlight in hand, reading of adventures we long to go on. But apart from the fleeting fads of Kung Fu movies, most people never have martial arts Master cross their mind. When the general public thinks martial arts, things like MMA and Jackie Chan undoubtedly come to mind. In fact research shows that in media, “martial arts are rarely discussed [but] they are often shown” (Bowman 130). Visual representation, nothing more, nothing less. But there is more. The fantastical realm of martial arts is what we’ve all seen, yet there’s still a real world hiding behind it. Who are those individuals that walk into a martial arts school and still find themselves there decades later wearing a black belt with five stripes and holding the title Master?

Enter 8th Degree Elder Master John Keller, a Shaolin Kung Fu practitioner for forty-two years, and 4th Degree Black Belt Robert Patraw, a Shaolin practitioner for twenty-four years; both practicing at the Chinese Shaolin Center for Martial Arts. Your mind may immediately jump to the stereotypical martial arts Master, evoking those fantastical images of old men with arrogant dispositions and long white beards, later revealed to possess near supernatural fighting abilities. While entertaining, this stereotype proves to be untrue. Both men are fit, energetic, and lacking in any long white beards, though both are extremely skilled. While it’s clear Master John Keller has long surpassed the initial rank of mastery awarded at 5th degree black belt, Robert Patraw is now on the cusp of entering into the mastery realm. He is slated to test into 5th Degree Black Belt this coming June of 2022. But what does it mean to be a Master of a martial art? It’s not as straightforward as the common titles we know such as Professor, President, or Doctor.

If you search the word “master” in the Merriam-Webster dictionary online you’ll get a long list of definitions. Scrolling down a bit will finally bring you to one that might apply to a martial artist, “An artist, performer, or player of consummate skill,” (“Master,” def. 1.d.). It’s vague to say the least. During his interview, Robert Patraw sitting in the back of the school with the sounds of Tai Chi class in the background, offers another take on mastery, “it’s the ability to start to interpret on your own, and make it (forms) your own.” He emphasized this concept of interpretation leaning forward, saying what sets a Master apart is, “the ability to interpret the spirit of the form, not just be a carbon, cookie cutter, cut out…” So nobody likes a copycat. Even the best writers and musicians are celebrated for their style, the hours of sitting and strumming on the guitar or the hundreds of stories tossed to the garbage aren’t all for nothing. From those passing years emerges an individualization of their art form. In his interview, sitting behind his desk as he leans back casually in his chair, Master John Keller went a different route with the definition,

I’ll tell you what it doesn’t mean. It doesn’t mean that you have mastered everything perfectly and that you have reached the pinnacle of your training. Mastery means, to me, that you have mastered the concepts and the ideas in order to continue to pursue training for the rest of your life.Master John Keller

He went further to say that, “You have to let go of the notion that you know everything, because you don’t, even at the mastery level.” Oddly enough, the rank of Master itself isn’t fully rooted in martial arts. Grandmaster Doc-Fai Wong, a Master in the martial art of Choy Li Fut Kung Fu, explains the history in regards to Chinese martial arts, “All the titles for addressing students and teachers are based on Chinese family titles. For example, sifu means teaching father…these titles have little to do with formal ranking or learning levels,” (Wong plumblossom.net). Later in his article, Grandmaster Doc-Fai Wong revealed how the term mastery entered into the world of martial arts:

When American GIs imported Japanese and Korean martial arts into North America after World War II, many of the early teachers began to devise more- extensive ranking systems. The Karate-do and Taekwando organizations in the U.S. and Europe were some of the first schools that used colored belts, degrees, and professional titles for ranking purposes .(Wong plumblossom.net)

This brings us to belts, the tell tale symbol of martial arts. The moment you put on your white belt, fumbling to tie a knot that at first seemed so complicated, the desire for a black belt begins to take hold. You watch the black belts go through impossibly long forms with ease, thrusting spears or slicing the air with swords. They kick and spin and step in intricate sequences that, as a white belt, seem unbelievably complicated. You wonder what their secret could possibly be as you stand there struggling to hold the most basic stances. The black belt itself seems the logical answer, but perhaps not.

The idea of belt wearing itself can be attributed to Kano Jigoro, the founder of Judo (McCarthy 26). “Kano foresaw the need to distinguish the difference between the advanced practitioner and the different level of beginners, and so he developed the dan/kyu system,” (McCarthy 26). This system of belt ranking is the same used at the Chinese Shaolin Center for Martial Arts, “dan” denoting the rank of black belt such as 1st Dan Black Belt, and “kyu” denoting the rankings below black belt which at Chinese Shaolin Center for Martial Arts are white, yellow, blue, green, and brown. But look closer and even something as simple as a belt turns out to be more meaningful. Just like Master John Keller and Robert Patraw, Kano Jigoro,

emphasized that the attainment of the dan merely symbolized the real beginning of one’s journey. By reaching black belt level, one had, in fact, completed only the necessary requirements to embark upon a relentless journey without distance that would ultimately result in self-mastery, (McCarthy 26).

You may want to take note that words like “fighting” and “combat” have yet to come up in any of these definitions.

This notion of a deeper meaning carries over into both the growing academic study of martial arts as well as the history of traditional Chinese martial arts.

Each emphasize a multidimensional aspect of the practice. Sixt Wetzler, a researcher and committee member for Martial Arts and Combat Sports in the German Association for Sports Sciences, says martial arts in and of itself is a, “network of different dimensions of meaning ascribed to martial arts practices” (Wetzler 2). The dimensions he refers to are- preparation for violent conflict, play and competitive sports, performance, transcendent goals, and health care. Going further he says that, “One aim of martial arts studies is to observe, understand, and interpret martial arts in their various representations, their development, form, and cultural meaning” (12). While the first three of his dimensions are fairly straightforward in their meaning, “transcendent goals” is worth looking more closely at. Words like ethereal or spiritual generally come to mind hand in hand with transcendent, but again we may ask, what does that mean in the world of martial arts? In his interview, Master John Keller says, “And there’s so many things to learn along the way, and it goes way beyond just learning martial arts…martial arts is designed to enhance you as a human being.” Later on he says, “as you journey through life and Shaolin (Kung Fu) is a part of that, it helps to shape and mold you to become part of society.” Physicality, fitness, fighting, is only one small piece of a much larger picture. Learn a tiger form and do you simply become aggressive, clawing and lashing out as the animal would? Or do you see the power in aggression balanced with that of control? If you hear the history of a form do you gain nothing more than an interesting story? Or do you learn to appreciate another culture and grasp the importance of its preservation? When you learn to meditate is it nothing more than conscious breathing? Or is it the foundation for self reflection, regulation, and even a sense of spirituality? This concept of personal development holds true when you look into the history of one of the most famous Chinese martial arts, Shaolin Kung Fu; the martial art which Master John Keller, Robert Patraw, and I practice.

In the book The Shaolin Monastery: History, Religion, and the Chinese Martial Arts, the historical background and complexities that surround the development of martial arts are revealed to support this multidimensional viewpoint. Factors such as the tense political climate, religious beliefs, and interest in health were all intrinsically tied to the development of what we now know as Shaolin Kung Fu. “Practitioners were no longer interested in fighting only. They were motivated instead by considerations of health, at the same time that they sought spiritual realization” (Shahar 137). Even the very practice of empty handed techniques came about for more than just combat reasons, “…Shaolin monks were intrigued by the philosophical and medical dimensions of the new bare-handed styles” (137). These ancient monks saw beyond the surface of martial arts fighting. They realized that through their practice they were cultivating the self, seeing what the human body could do. The inevitable injuries and newfound skills naturally connected to the realm of medicine, but turning to philosophical questioning wasn’t necessarily surprising either. In the act of achievement and failure, humans often become introspective, questioning the world around them and their very existence. All of this, from the martial skills to the medicinal endeavors and philosophical questions is reflected in the stories handed down from generation to generation. This traditional side of martial arts is intrinsically tied to what it itself deems mastery.

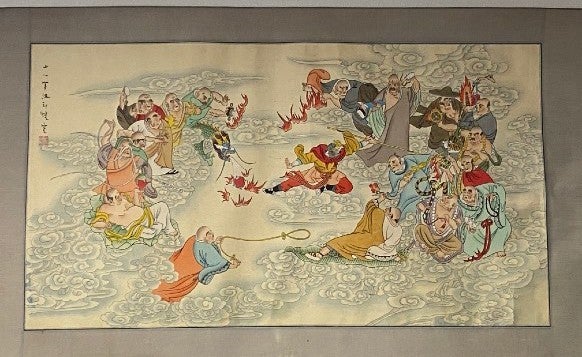

Were you to attend a class at the Chinese Shaolin Center for Martial Arts, the health, religious, and philosophical side would become all the more clear. Following the traditions of the Grandmaster, Master John Keller makes sure to relay the same stories and details about forms that have been passed down for decades. From time to time, he sits the class down in a way somewhat reminiscent of childhood story time. He slowly walks back and forth delving into classic Chinese stories like the Monkey King or the Eight Immortals. Students sit in rapt attention, all eyes on him, as his demeanor lights up and he begins to emphasize the events, demonstrating different techniques. Some of the black belts have heard the stories countless times, but still they listen just as intently; it is the history of the art they love. Beyond the classic Chinese stories, Master John Keller will cover the health benefits and style origins, pointing out pressure points on sometimes unsuspecting students who decided to sit a bit closer than the rest, or giving a brief geography lesson. In this way the cultural aspects of Shaolin Kung Fu are shared and preserved for the next generation, a privilege earned through mastery.

So why has martial arts earned a reputation solely for its combat?

Master John Keller points out that after forty-two years in the martial arts world and thirty-two years running a martial arts school, “the biggest thing that I’ve seen over the last forty years is the commercialization of martial arts. It’s become very commercial, and in some ways it’s distorted the true values of what traditional, classical martial arts teach. It’s more about selling what’s popular.” And nobody can deny that a good movie fight scene is popular. You see the anti-hero leaping off walls and landing as light as a feather, or the battles where fists fly as fast as bullets yet the fighters dodge even faster. This assumption draws right back to how the public views martial arts according to what they’re presented with. When all you are ever shown is fighting in relation to martial arts, it’s easy to assume that’s all there is to it. When it comes to mastery Master John Keller expanded on that fact saying that the public,

…they will compare that to what they know, and what most people know is what they see on television and in the movies [but] you can’t compare the two because they don’t exist side by side like that. And so unfortunately what a typical outsider, outside the martial arts, may view a Master of being is exactly what they see in the movies, someone with spectacular and unlikely skills.Master John Keller

Now I will say there are some immensely talented martial artists, their foot rising far above their head for kicks, or balancing effortlessly on one leg while throwing a flurry of strikes, even kicking and dropping down into the splits. However not every martial artist can do things like that, and certainly not fight beneath moving trains like Jackie Chan in one of his many movies. Even Robert Patraw freely admitted that contrary to his initial belief that black belt meant you must be proficient, “…you get to black belt and you think well um, I still kind of suck!” It’s true, much like a child assumes adults have all the answers, black belt is only the beginning. You walk into a class of individuals, some of whom have been there for a mere year, and others for over twenty. Yet you all line up together, practice together, spar together, and learn together. You know far less than the senior black belts, but you still see them learning right along side you, practicing their kicks and punches or fumbling on the difficult moves of a new form. There is no end all be all of knowledge.

However, commercialization does have a place in the world of martial arts that doesn’t detract from its other qualities. It’s found in a kind of preservation different from passing down stories. In an article published in the New York Times newspaper, writer Howard French explored that very topic while visiting the real Shaolin Temple in China. He asked, “Is Shaolin Kung Fu popular entertainment or solemn exercise? Is it a money maker or tool of spiritual mastery?…The short answer to all these questions is, of course, yes.” There is a very real connection between popularity and preservation. Imagine walking into an ancient temple, the ground uneven beneath your feet, the air heavy with humidity. You see buildings that tell of bygone days with their time worn architecture and artwork, yet all around you are tourists walking around in brightly colored shirts, snapping photos, and meandering in and out of a gift shop. This is the reality of the Shaolin Temple. When interviewing the Shaolin Temple’s abbot Yongxin, Mr. Howard broaches the subject of the popularity’s effect on the temple to which he receives the answer, “‘We are not against pursuing commercial interests. We only hope we can play a positive role in society, while not violating a spirit that is 1,500 years old.’” Master John Keller expressed the same mindset, “I’ll be the first to admit, I love it when martial arts movies come out because I want people to become more aware, but it tends to kind of disguise what really goes on in a martial arts school.” So it truly is a balance between the desire of Masters to preserve and share the art form that is Shaolin Kung Fu while also keeping the business that does so alive.

To do so isn’t always easy. To stay alive schools must thrive in a climate that isn’t necessarily forgiving. Research published in the International Journal of Sports Marketing and Sponsorship reveals that, “Even if enrollment in martial arts program remains to be a popular sport activity option, high dropout rates and falling participation rates are increasingly evident in the martial arts industry in recent years” (Minkil and Zhang 1). The answer to why is not exactly surprising. Simply put, it’s about the student’s resources and ability to balance their life.

In this study, the retained items, including time, location, transportation, crowdedness of school and affordability were found to be significant indicators among the structural constraints. Previous studies have consistently found that more than 30% of respondents’ perceived constraints were based on lack of money and time.(Minkil and Zhang 14)

This reality only emphasizes what students who attain Mastery manage to accomplish. Ask a black belt of any rank and they will tell you that to succeed in martial arts requires devoting a great deal of time and effort. Apart from multiple classes a week that can range anywhere from an hour to an hour and a half, to be truly successful you must also dedicate time to practice on your own as well; not to mention the time it takes to write out notes if that’s part of your learning process.

So one might start to wonder, seeing that mastery and martial arts is so much more than learning to fight, and that a deep level of dedication is required, what sets those few individuals apart who successfully reach that rank?

Believe it or not, talent doesn’t play much of a role in this. Master John Keller took the time to describe these students, “They’re focused. Their ability to really

master their scheduling and their timing, because as you advance it gets more demanding, more is asked of you, and so it’s all about just being able to juggle everything at once.” He went even further to say that,

You have to be extremely disciplined, you have to be able to take criticism all along the way. You have to be able to want to improve. And so, to pursue that higher level, you have to invest yourself one-hundred percent emotionally and physically, but also learn how to do it in a way to where it doesn’t distort or disturb the rest of you life.Master John Keller

Robert Patraw expressed the same sentiment, “It’s fun as long as it’s not a burden…if it’s part of your routine, and it’s well communicated and it’s comfortable and relaxing and not stressful.” I too can attest to that fact. My fellow classmates and I often lament the struggles of work or school, standing in a circle before and after class like workers at a water cooler. Perhaps some would call in complaining, watching us shake our heads and groan, but in reality its a kind of bonding because we’re still there. We’ve watched our fair share of practitioners pass in and out of the doors, not likely to be seen again, weapons left behind for somebody else to use. Those who attain Mastery have watched even more disappear. The core group has a different level of devotion to the art. Yes, it takes discipline to come to class on the days where you’re exhausted, and even more discipline to practice consistently, juggling upwards of twenty plus forms just to reach 1st Degree Black Belt, but the real challenge presents itself in how you integrate it into the rest of your life.

In the end, just as there’s no single type of person capable of achieving mastery, there is often no magical moment where you decide to pursue it.

Dedication is a journey, a learning experience. As both Master John Keller and Robert Patraw put it, it’s a process that simply evolves over time. Robert Patraw more clearly described it saying, “It was an organic kind of movement into me being a lot more active and appreciating…” Master John Keller agreed as well, “It was a

progression, it wasn’t really one event that caused me to shift that way of thinking. The more I learned about it the more I realized I wanted to know more about it and next thing I know ten years have gone by.”

At the very heart of it all, martial arts and mastery are so much more than fighting and self defense; there are more pieces to the puzzle all rooted in deep devotion to a lasting tradition of self cultivation and skillful interpretation. Yet, similar to being asked to define words like love or joy, it’s almost easier to show it rather than to merely describe it.

You see Master John Keller standing tall in front of the class of black belts he has trained from the start, a steady expression on his face, eyes calculating and knowing as he looks around. There’s no doubt that with a glance he can see what’s lacking in your stance or the move you missed in a form, though often only a slight furrow of the brow gives it away. He commands the room without the need to yell, yet every instruction he calls out all but echoes in the building as he paces back and forth observing. The time for warmups and conditioning passes in a haze of sweat and then comes the time for learning and practicing forms. Even without any uniforms or belts, there would be no doubt who’s the most skilled in the room. Every movement and strike he does is undeniably deliberate and fast, his fist or his foot flicking out in a blur that you’re more likely to feel than to see. Pointing at a student he explains where precisely to hit, how, and why, carefully demonstrating with an accuracy that leaves the strike centimeters from the target point. He breaks the form down, step by step, calling it out while simultaneously correcting the mistakes of the students following along. Eyes in the back of his head doesn’t even begin to cover it. This is Mastery.

You hear Robert Patraw before you see him, bursting into the room with an aura of energy that rivals the energizer bunny. He greets everybody he passes, immediately diving into practice while waiting for class to start. Drunken style is his focus. He stomps and sways so deceivingly you could swear he must have stopped at a bar on his way to the school. Then, like a light switch flipping on, in a blast of power he goes into a flurry of well aimed strikes. The next moment he’s switching back to the drunken demeanor as if nothing had happened, flowing into the ruse seamlessly. He stumbles, he staggers, head lolling slightly, every motion of his body says intoxicated, leaving any opponent hopelessly confused, until again the switch flips and he’s on the offense again, clean cut strikes that have proven to be powerful enough to knock equally large men back during punch and kick practice. This is what it means to be ready for Mastery.

And that truly is the reality of being a Master. They are not the immortals or heroes of traditional Chinese tales, nor are they mystical fighters possessing supernatural abilities. They are people, unique in their own right, who have devoted themselves to an endless journey of self cultivation and whose skill has been shaped around them as an individual. Their strengths are emphasized, their weaknesses are improved, their forms and interpretations are as distinctive as the life experiences that have molded them. This journey of becoming and being a Master is one that no belt can ever truly encompass and no one definition can ever hope to explain.

Works Cited

- Bowman, Paul. Deconstructing Martial Arts. Cardiff University Press, 2019. PDF. 16 February 2022.

- French, Howard. “So Many Paths. Which Shaolin is Real? The Reply: Yes.” New York Times (1923-), 10 February 2005, pp. 1. PDF. 16 February 2022.

- Keller, John. Personal interview. 27 January 2022.

- Kim, Minkil, and James Zhang. “Structural Relationship between Market Demand and Member Commitment Associated with the Marketing of Martial Arts Programs.” International Journal of Sports Marketing and Sponsorship, vol. 20, no. 3, 5 August 2019, pp. 516–537. PDF. 16 February 2022.

- “Master, N (1).” www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/master. Merriam-Webster, 2022. Web. Accessed 22 February 2022. (“Master,” def. 1.d)

- McCarthy, Patrick, et al. “The Dai Nippon Butoku-Kai.” Ancient Okinawan Martial Arts: Koryu Uchinadi, Tuttle Pub, Boston, 1999. PDF. 16 February 2022.

- Patraw, Robert. Personal Interview. 2 February 2022.

- Sandford, Glenn T., and Peter Richard Gill. “Martial Arts Masters Identify the Essential Components of Training.” Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, vol. 24, no. 1, 1 January 2019, pp. 31–42. PDF. 16 February 2022.

- Shahar, Meir. The Shaolin Monastery: History, Religion, and the Chinese Martial Arts. University of Hawai’i Press, 2011. PDF. 16 February 2022.

- Wetzler, Sixt. “Martial Arts Studies as Kulturwissenschaft: A Possible Theoretical Framework.” Martial Arts Studies, no. 1, 2015, p. 20-33. PDF. 16 February 2022.

- Wong, Doc-Fai. “Doc-Fai Wong Martial Arts Centers 黄 德 輝 國 術 學 院.” Professional Titles In Martial Arts – Plum Blossom International Federation, https:// plumblossom.net/Articles/Inside_Kung-Fu/July2005/index.html.