My name is Jasiel Ramirez, and I’m from Caldwell, Idaho. I’m currently pursuing undergraduate degrees in Sociology and Ethnic studies with minors in Gender Studies, Latin American Studies, and Mexican-American Studies. Having experienced various adversities due to my marginalized identities, I have developed a passion to work with marginalized communities who face oppression at the hands of unjust systems of power. My ambition is to work with a nonprofit organization that provides intersectional, holistic resources for marginalized communities such as people of color, LGBTQ+ identities, limited-income folk and more. As a future community educator, sociologist, and lobbyist I will be a catalyst for change for my community and for marginalized communities alike. In my free time, I enjoy spending time with my friends, dancing, binge-watching tv shows, and reading.

Student Governance: An Ethnographic Study

The Associated Students of Boise State University (ASBSU) was established as the student government at Boise State University for two fundamental purposes: first, to “facilitate educational, intellectual, social, and cultural engagement at the University,” and second, “to advocate for the interests of students at the University.” As a governing entity “run entirely by students, for students,” ASBSU must commit to the empowerment of all students (Home, 2018). In saying this, the disparity between those who are “governed” and those who “govern” must be diminished. This study provides insight on how ASBSU operates within a framework that Chandra Reyna, a former Boise State University graduate and McNair Scholar, calls “racialized resistance” and how dominant and subordinate groups in ASBSU are subjected to nuanced colorblind ideologies ingrained within organizational norms, rhetoric, and actions (Reyna, 2017, pg.72).

ASBSU’s structure is comprised of four entities: Executive Council, Inclusive Excellence Student Council, Student Funding Board, and Student Assembly. These entities assume certain roles and each is an integral component to ASBSU to fulfill their two fundamental principles. Each entity manages internal and external affairs of ASBSU which vary from funding, social justice work, public relations, and to “collaborating with university administrators to ensure that the student voice is being considered in decisions at Boise State” (Home, 2018).

My research sought to answer the question “how does ASBSU represent all students of Boise State University?” As the official student government of Boise State University, ASBSU holds power on various individual, interpersonal, and institutional levels within the administration, policy, and campus culture. With a commitment to represent all students, ASBSU must work towards uplifting the voices of any and all historically marginalized subordinate groups. This study discerns factors within ASBSU that influence the representation of all students, essentially identifying if ASBSU thoroughly uplifts and or further marginalizes subordinate groups. While multiple identities will be discussed, an emphasis is placed on race due to the limitations of research conducted for identities such as students with disabilities, undocumented students, and more.

LITERATURE REVIEW

In her study, Reyna sought to explain how Boise State University’s culture influences the understanding of racial phenomena by examining the ways students navigate issues of racial inequity. By analyzing the participating students’ discussions of themselves, the university, and their own perceptions of local events, Reyna uncovers the levels to which participants subscribed to colorblind ideologies while emphasizing the role of the university in hindering the focus on racial justice by overwhelmingly framing diversity. Reyna’s data reveals that the culture of Boise State University has led to the racial orthodoxy that Reyna calls “racialized resistance.” This racial orthodoxy finds that a student’s race acts a “master status” that determines which strategy—strategic suppression, acceptable resistance, avoidance, or power analysis—they (can) use when participating in politicized civic engagement (Reyna, 2017, pg.74).

A strategy Reyna discusses within the racialized resistance framework is “strategic suppression.” Students who use this strategy are able to identify the factors that contribute to large system inequities in housing, education, the justice system, and day-to-day interactions. In discussing with students, Reynda has identified that the 29% (7/24) of participants in Reyna’s study, shift their narratives when asked about issues in their local community or at Boise State University, resulting in the “minimization of issues that students of color face.” Reyna further states that these students have the ability to refrain from holding “racist” labels as they often pass as “progressive liberals” (Reyna, 2017, pg.75-76). Another strategy Reyna has found that students employ is “power analysis.” Students using this strategy continuously acknowledge the inequities they witness and or experience and actively take conscious action to oppose traditionally accepted racial ideologies. These students work to dismantle the multifaceted structural oppression (Reyna, 2017, pg.79).

At Boise State University, Reyna’s study finds network centrality as a proxy for race. The higher social and cultural capital a student obtains, the higher their level of network centrality. In further data collection, Reyna identifies a pattern of which students had higher network centrality—white students. White students overwhelmingly had the highest levels in comparison to students of color who had lower levels and were “ positioned on the adjacent or peripheral edges of the centric social system.” At the core of the university’s centric social system is access that provides students with seats on student government, funding boards, and student assembly; This means that white students are essentially granted the “authority” to shape the student body’s experiences on campus by being at the core of Boise State University’s network centrality—ASBSU (Reyna, 2017, pg.75).

In “Student Governance: A Qualitative Study of Leadership in a Student Government Association”, Walter P. May finds that student governance holds presence at almost every college and university in the United States. May states that the widespread of this recognized presence by colleges and universities confirms the significance of student governance in higher education (May, 2009, pg.4) The evolution of student governance has evolved into a model similar to the United State’s national system of governance consisting of executive, judicial, and legislative branches. Throughout college and university campuses, these student-led governments share similar roles and responsibilities of serving as an official voice of students, allowing student participation in decision-making, responsible collection of student fees and more. In essence, student governance has a great influence in molding the social and cultural experience in colleges and universities (May, 2009, pg.455).

METHODS

This study centered on a qualitative approach that consisted of anonymous surveys and personal interviews. All of ASBSU—Executive Council, Inclusive Excellence Student Council, Student Funding Board, and Student Assembly—was given the opportunity to partake in this research. Esperansa Gomez, the current Vice President of Inclusive Excellence, operated as the liaison between me and ASBSU by communicating with ASBSU what my research was about, sending out surveys, and following up with me.

The surveys included multiple choice and open-ended questions that asked participants to identify what dominant and or subordinate groups they identified with, their views of ASBSU, and what their perception of the representation within ASBSU looked like. All surveys were conducted anonymously by using Google Forms and can be in the Appendix. There was a question in the survey that allowed participants to enter their email if they would be interested to be personally identified and followed-up with for an interview.

During interviews, participants were asked to identify pressing challenges they believe marginalized students are experiencing at Boise State University, what areas they believe ASBSU could improve the representation of marginalized identities, if they have witnessed resistance by dominant groups in ASBSU to uplift marginalized voices and what is being done by ASBSU to currently meet the needs of marginalized students which can be found in the Appendix. Each question was specifically made in regards to the top five subordinate groups and top four dominant groups that survey respondents said are/are not represented in ASBSU.

In adherence with Chandra Reyna’s work, “How Far Does Influence Go? Racialized Resistance and University Culture”, I will be utilizing Reyna’s framework of racialized resistance to analyze how ASBSU subscribes to the marginalization of racial minorities. Racialized resistance is defined as “a student’s race acts a master status and determines how they can participate in politicized civic engagement” (Reyna, 2017, pg.72).

All information collected from the surveys and interviews is to be considered true to each individual as they are based on their opinions and observations. By employing qualitative methods, this study focuses on the meanings of the participants’ experiences. Data and statistics derived from Boise State’s “Facts and Figures” and will be used to analyze the implications ASBSU has on the entire Boise State University community.

RESULTS AND ANALYSIS

Initially, I intended to identify biases that resided within ASBSU and how these biases influenced the representation of all students. Similarly to Reyna’s study, I was unable to distinctly identify what ideologies students who took surveys had. Instead, the focus of this paper centers on the demographics of ASBSU in relation to the representation of historically, privileged dominant groups and marginalized subordinate groups.

DEMOGRAPHICS

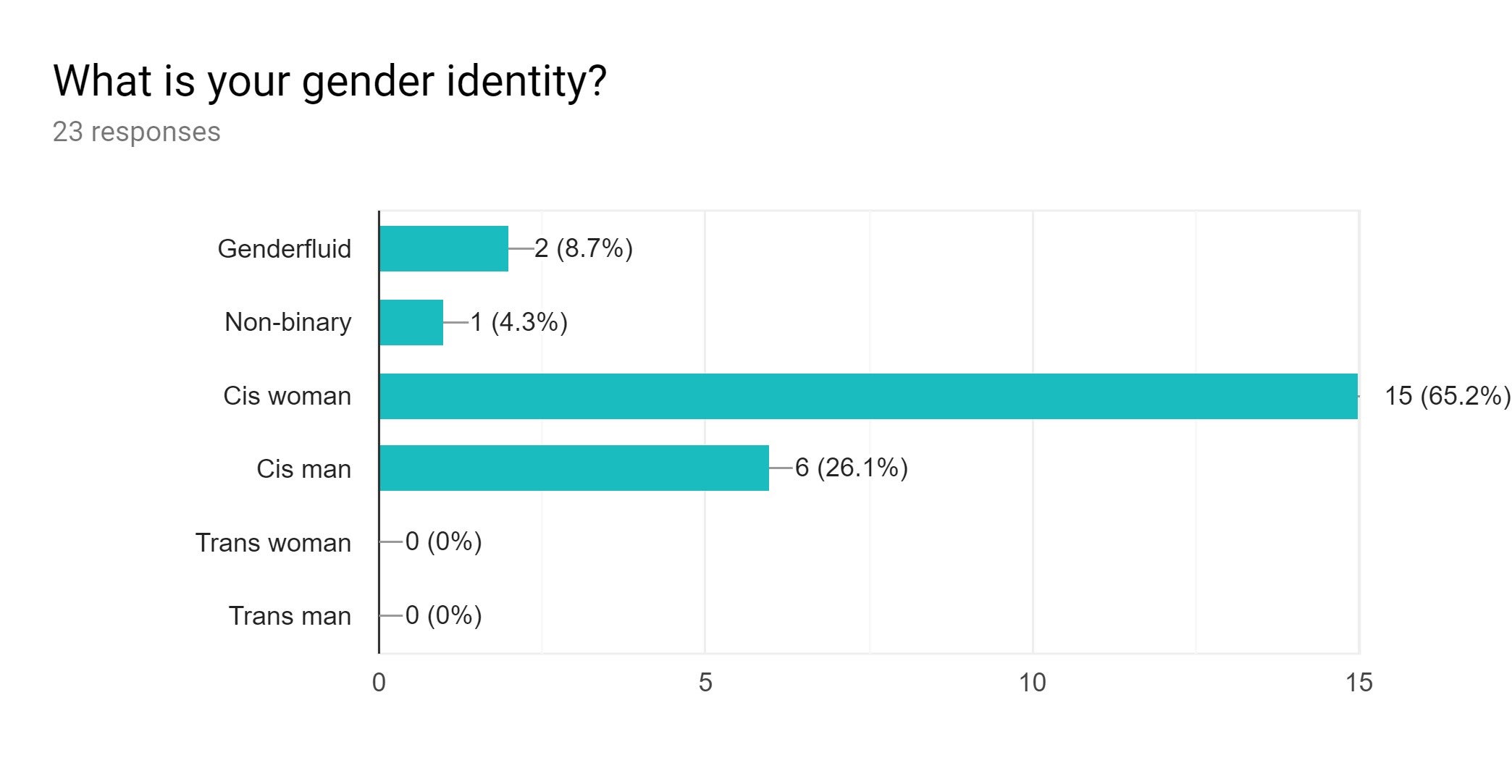

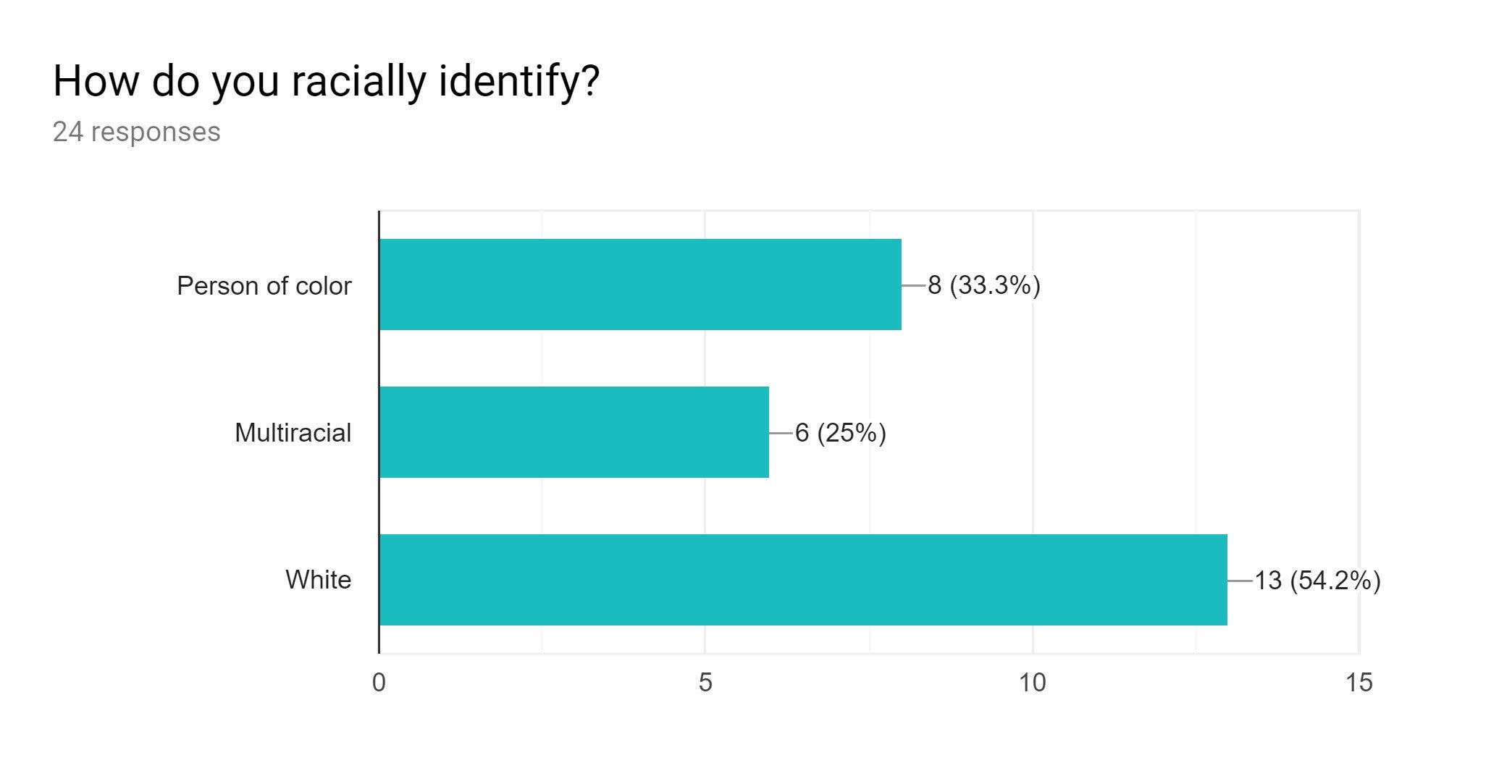

In my survey, I decided to ask folx what dominant and or subordinate groups they identify with in an effort to analyze how the identities that makeup ASBSU directly affects the representation of all students. I will be focusing on both gender and race as that has played a visibly significant role within the study.

When asked the question “what is your gender identity,” 15/23 (65.2%) said they identify as a “cis woman,” making up more than half of the group; 6/23 (26.1%) said they identify as a “cis man”; 2/23 identify as genderfluid ( 8.7%); and 1/23 (4.3%) identify as non-binary. In response to the question “how do you racially identify,” 13/24 (54.2%) people, more than half of the group, identify as white; 8/24 (33.3%) identify as a person of color; and 6/24 (25%) identify as multiracial, which can consist of races such as white, Black, Brown, Asian, etc (Appendix – ASBSU Survey). In looking at these demographics and how these identities intersect, the majority of this group is made up of white, cisgender women followed by white, cisgender men as the second highest majority. These demographics of ASBSU accurately portray Reyna’s results of network centrality, which states that white students are closer to the core of Boise State University’s social central system, granting them more access to seats on student government, funding boards, and student assembly (Reyna, 2017, pg.75).

REPRESENTATION

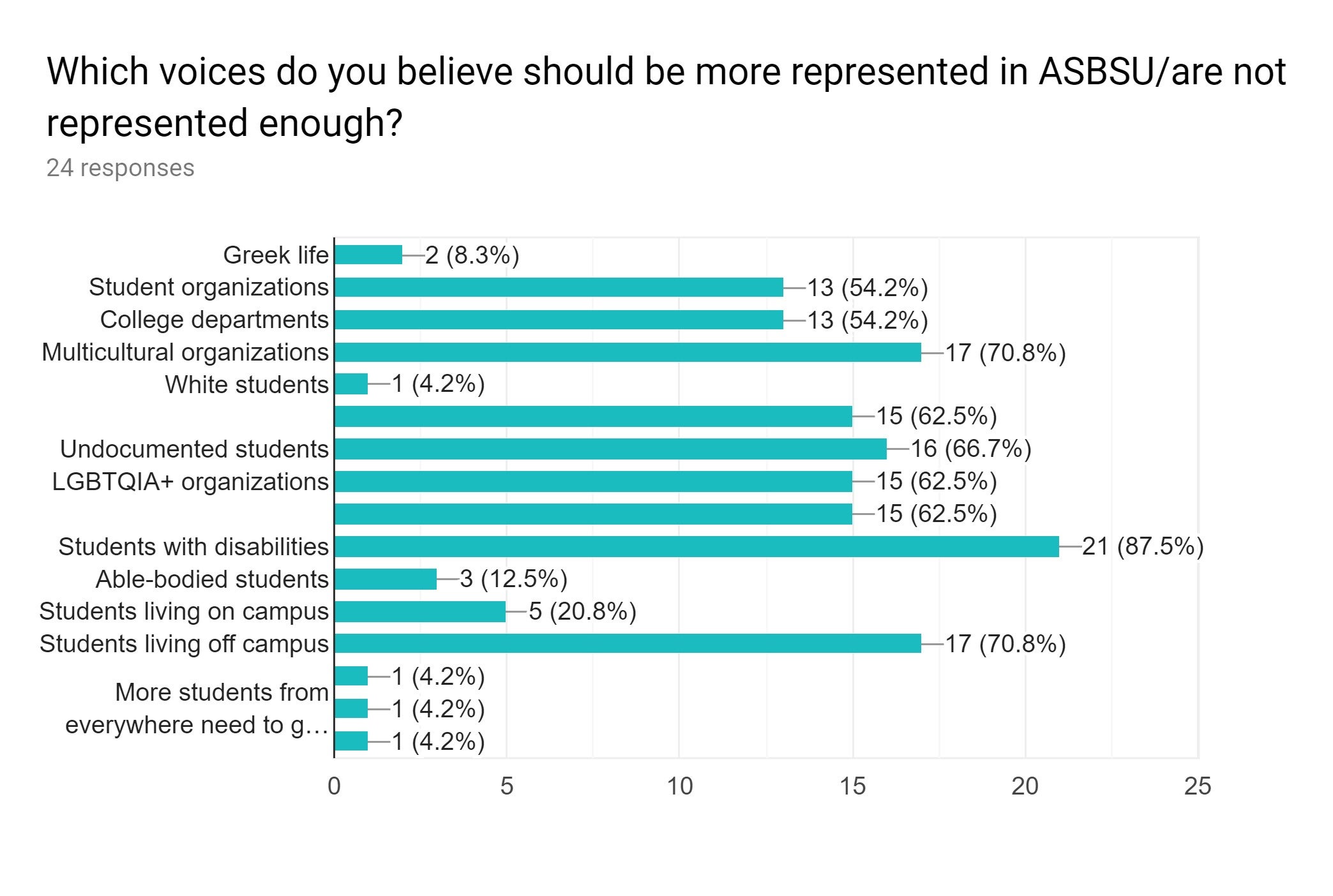

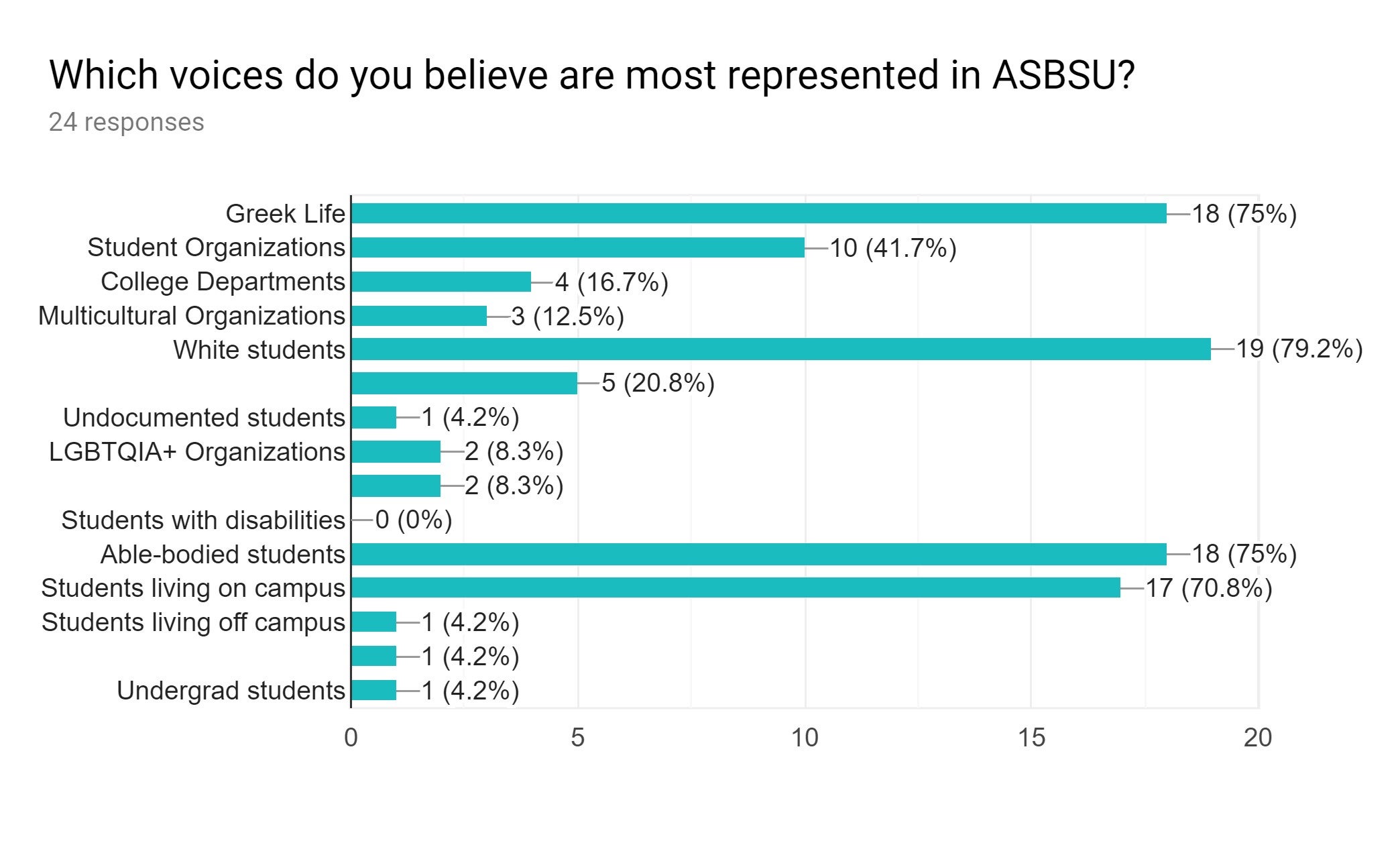

In my survey, students answered two questions regarding representation in ASBSU. Representation is very broad and it should be noted that, when followed up in interviews, representation has come to include but is not limited to, marginalized groups being in positions of power, consciously making decisions—in policy work, outreach, legislation, and administration—that are equitable and representative of all student voices, and actively working from a lens of the “Last Girl Framework,” a framework that was introduced by the IESC to ASBSU that centers on the notion that uplifting the most marginalized individual innately uplifts everyone. The first (multiple-choice) question about representation in the survey that was asked to participating students is “which voices do you believe should be more represented in ASBSU/are not represented enough?” The top five identities that survey participants chose were not being represented enough were students with disabilities, multicultural organizations, commuters, undocumented students, and tied with an equal amount of votes was LGBTQIA+/Orgs/POC Students. Conversely, the top four identities that participants voted were most represented in ASBSU were white students, Greek life, able-bodied students and students living on campus.

These results are important in analyzing the representation of students as the implications for what students in ASBSU believe means that large amounts of students are not being uplifted and are instead having their voices further marginalized. Upon researching the demographics of the entire student population at Boise State University, the majority of ASBSU students who participate believe ASBSU is not representing: 6,928 Non-white/Students of Color (Facts and Figures, 2019) and 413 Non-US Citizen/Perm Resident students (Boise State University, Fall 2019, Census Day Enrollment Profile). Currently, there Boise State University does not have information regarding the demographics of commuters and LGBTQIA+ identifying students.

At Boise State University, the awareness of racial inequities has grown by surges of racist acts within classrooms, residence halls, and student organizations. Despite this heightened racially aware campus, Kaleb Smith, a cisgender white man and Student President of ASBSU recognizes that there are white students within ASBSU who still resist to empower and uplift marginalized voices. When asked about the resistance he has witnessed by dominant identities within ASBSU to empower and uplift marginalized voices, Smith replied that it is a “matter of education.” Not everyone within ASBSU realizes the privileges they have and the challenges that marginalized identities face. Smith states that it is important to educate these resistant students so they can recognize the significance of historically marginalized identities and their challenges (Smith, 2019).

In the context of strategic suppression, Bibiana Ortiz a genderfluid, non-binary student of color and IESC Council Member identifies the use of this strategy in discussing the emergence of the IESC. Last year, when the IESC was an unofficial student organization, there was “hella pushback” to integrate the IESC with ASBSU. Several students who were, at the time, in ASBSU and who had already graduated knew what this integration meant—a holistic approach to diversity and inclusion—and argued that the IESC was racist. These students clearly employed strategic suppression as they minimized the racial inequities of students of color by interfering with these structural changes to ASBSU by arguing under the pretense that this integration would do more harm than good (Ortiz, 2019). According to Kaleb and Bibiana, there are still several students within ASBSU who still do not fully understand the full purpose of IESC and display resistance to change despite knowing what it means for marginalized identities.

Although results from the survey and interviews have identified that several members in ASBSU currently uphold strategic suppression, I found that several students do not and instead, utilize power analysis. This is credited in comments made by Angela Aninon, a cisgender woman of color, in her interview. When asked how ASBSU is meeting the needs of marginalized students, Angela replied that the integration of IESC and emergence of the Vice President of Inclusive Excellence has offered great insight on diversity and inclusion. In utilizing the Last Girl Framework, the ASBSU has been able to frame challenges and solutions to center marginalized students (Aninon).

CONCLUSION

Grounded within Boise State University, ASBSU holds a platform to critically challenge students in their educational, intellectual, social, and cultural growth while simultaneously uplifting the students’ interests. By utilizing components of Reyna’s concept of “racialized resistance” such as “strategic suppression” and “power analysis” this study has been able to critically analyze the ways in which ASBSU uplifts and marginalizes students who identify within historically marginalized subordinate groups. The survey and interviews conducted identify, by ASBSU members themselves, that ASBSU has progressed greatly by the integration of the IESC and there is still much work to be done in order to work towards the representation of all students throughout the entirety of ASBSU.

APPENDIX

ASBSU Survey:

ASBSU Interview:

Works Cited

Aninon, Angela. Personal Interview. 2019

Boise State University. (Fall 2018). [Census Day Enrollment Profile Fall 2018]. Retrieved from Https://www.boisestate.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/20/2018/11/Census-Dy-Enrllment-Profile-Fall-2018.pdf

“Executive Council.” (2018). Boise State University. Retrieved April 2018. Retrieved from https://asbsu.boisestate.edu/executive/

“Facts and Figures.” (2019, February 19). Boise State University. Retrieved from https://www.boisestate.edu/about/facts/

“Home.” (2018). Boise State University. Retrieved April 2018. Retrieved from https://asbsu.boisestate.edu/

Ortiz, Bibiana. Personal Interview. 2019

May, Walter Preston, “Student Governance: A Qualitative Study of Leadership in a Student Government Association.” Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2009. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/eps_diss/36

Reyna, Chandra. (2017). “How Far Does Influence Go? Racialized Resistance and University Culture,” McNair Scholars Research Journal: Vol. 13 : Iss. 1 , Article 15. Available at: https://scholarworks.boisestate.edu/mcnair_journal/vol13/iss1/15

Smith, Kaleb. Personal Interview. 2019