I moved to Boise about fifteen years ago at the age of ten. I was born in San Antonio, Texas and raised in Austin but I trace my origins to long before I was born. My Mom’s family came to the US in 1975 after the Fall of Saigon. After transitioning to life in America, they quickly climbed the social rungs of society and she became a wildly successful entrepreneur in the state of Texas. Most of what I know about ambition, perseverance, and strength I learned from watching my Mom lead by example. Every ounce of who I am is inspired and cultivated in her image.

I am a proud graduating senior in the Political Science Department with an Emphasis and Public Law and Political Philosophy. I will be attending law school in the Fall at either Lewis and Clark or Georgia State University. When I am not studying, my favorite pastime is spending time with my beloved friends and family along with any animals I can find.

Demystifying the Model Minority Mythology

Investigating how the model minority myth affects Asian American women living in the United States.

Introduction

Early in the summer of 2012, Asian American organizations took to the internet to criticize a study released by Pew Research Center regarding the “successes” of Asian Americans relative to other minority groups in the United States. The study stated that Asian Americans were the “New Immigrants” taking over Hispanics in annual migration. Relying on their survey data, Pew argued that Asian Americans were the “highest-income, best-educated and fastest-growing racial group in the United States. They are more satisfied than the general public with their lives, finances and the direction of the country, and they place more value than other Americans do on marriage, parenthood, hard work and career success” (Pew Research Center, 2012).

Upon hearing the conclusion of the study, non-Asian scholars who saw the report were left scratching their heads because they could not identify what the controversy was all about. Three days later, their confusion subsided when headlines like, “Asian Americans Respond to Pew: We’re Not Your Model Minority” surfaced and detailed critiques of the study were released (Hing, 2012). According to this article, the conclusions drawn by the study were overly simplistic and failed to account for a variety of factors that they believe skew the data and resultingly increase discrimination towards Asian Americans. While the data may have accurately portrayed details of some Asian Americans lives, the justifications found in the report utilized myths about Asian American culture mixed in with data to paint a misleading picture of Asian American livelihood (Hing, 2012).

Unfortunately, these portrayals have dire consequences. Firstly, Asian American women overrepresent in mental health statistics about suicide and depression (Chou & Feagin, 2015). Second, Asian Americans who are at risk are less likely to be identified. In the infamous Virginia Tech shooting, Korean American student Cho Seung-Hui was said to exhibit a variety of warning signs before the incident. These signs were overlooked in favor of stereotypes of Asian Americans as shy, awkward, and defenseless. In doing so red flags that preceded the attack were overlooked and racialized bullying of Cho was ignored. The invisibility and designation of racialized characteristics to Cho had a real impact on him and the over fifty people he wounded or killed that day. Finally, the model minority stereotype works to simultaneously praise and negate the accomplishments of Asian Americans. In doing so it portrays Asian Americans as a monolithic group with a singular identity and through this delusion erases the very real oppression that Asian Americans face in the United States today (Chou & Feagin, 2015).

This paper will attempt to separate Asian American mythology from reality by designing a study that identifies the ways that model minority stereotypes impact women from various Asian subgroups differently. Through asking a sample of Asian American women living in the United States a series of open-ended questions, this research study is designed to help understand the intricacies of Asian American livelihood and the impact that the model minority stereotype has on their lives.

Discussion of Research Question

One of the primary criticisms of the Pew Research Center’s study is that it attributed characteristics of different Asian ethnic groups indiscriminately to Asian subgroups as if all Asian American populations were the same. To fill in the gaps and balance misinformation spread by the Pew study, the research question for this paper is, does the model minority stereotype affect women in different Asian American subgroups differently? By asking this question, this paper aims to investigate the influences of the model minority stereotype on Asian American women from a diverse collection of Asian American subgroups.

Literature Review

To deliver a wholistic description of the model minority mythos and its implications, this section of the paper will aim to define model minority, discover its origins, describe how it is gendered, and introduce theoretical approaches to deconstructing the model minority mythology.

Definition

The model minority mythos, or stereotype, “is the notion that Asian Americans achieve universal and unparalleled academic and occupational success” (Museus & Kiang, 2009, p. 6). It is a positive stereotype that affirms Asian American prowess in school and work but asserts that Asian Americans are inept at doing anything outside of that scope. Despite countless examples that prove this stereotype to be inaccurate, it persists in shaping Asian American identity and perceptions of Asian Americans by other racial groups. The model minority stereotype is dangerous on numerous levels and can be linked to the overrepresentation of Asian American women in suicide and depression rates as well as underperformance of Asian Americans from Southeast Asian countries in academics (Chou & Feagin, 2015, p. 2).

While the phrase model minority was first used sometime during the 1960s, origins of the myth in the U.S. go as far back as the early pioneers. From these early origins, the history of racialized oppression in the United States began as follows:

Near their beginning, the new European colonies in North America institutionalized white-on-Indian oppression (land theft and genocide) and white-on-black oppression (centuries of slavery), and by the mid-nineteenth century the Mexicans and the Chinese were incorporated as dispossessed landholders or exploited workers into the racial hierarchy and political-economic institutions of a relatively new United States. (Chou & Feagin, 2015, pp. 4-5)

Through this history, Americans of color became accustomed to continual unjust treatment through their impoverishment and the simultaneous unjust enrichment of whites. This dynamic created a racial hierarchy where whites are at the top (Chou & Feagin, 2015, p. 5). The continuum firmly affixes whites at the privileged pole and blacks at the unprivileged pole, but the location of Asians in the hierarchy is highly variable. Their variability means that they risk at times posing a threat to Whites, as well as always often being placed higher on the scale than Blacks and Hispanics. Asians placement on the continuum is related to the creation of the model minority myth which simultaneously praises and negates the accomplishments of Asian Americans (Lee & Zhou, 2015, p. 117).

The phrase model minority became increasingly popular after the Pew Research Center released a study titled, “The Rise of Asian Americans” in 2012 (Pew Research Center, 2012). Widespread outrage among Asian American scholars and university students took over blogs and websites as Asian Americans vehemently criticized the assertions made by the research center. To be clear, there was little to no issue taken with the data itself, but with “the way in which Pew led readers to interpret their findings” (Lee & Zhou, 2015, p. 1). The study combined cultural myths propagated by anti-Asian stereotypes with facts about Asian American representation in higher education and the middle class. Through Pew’s misleading interpretation of the data: “the report served to endorse a neoconservative political platform that propagates the belief that high socioeconomic outcomes result from adopting the ‘right’ cultural values. Moreover, this framing reinforced the stereotype of Asian Americans as the ‘model minority’ that has achieved success the right way” (Lee & Zhou, 2015, p. 2). The model minority myth performs discrimination through first downplaying its impact on Asian Americans. It asserts itself as benign or even complimentary which erases the racial discrimination that Asian Americans face. That erasure or invisibility impacts Asian Americans in the following four ways.

First, the model minority myth provides a basis for racial harassment that impacts the identity formation and self-perception of Asian Americans starting as early as Kindergarten (Chou & Feagin, 2015, pp. 57-64). In Rosalind S. Chou and Joe Feagin’s, The Myth of the Model Minority, they include excerpts from interviews conducted of Asian Americans. In the third chapter they divide the excerpts by education level, and in doing so, juxtapose the experiences of different Asian Americans. While some interviewees cited the model minority myth as having no impact, or a positive impact on them, the respondents were all able to recount racist interactions that they associated with the model minority stereotype. Whether they faced discrimination in the classroom, workplace, or even in relationships, the assertion of the model minority stereotype resulted in negative experiences and self-perceptions of many of the respondents (57-82).

Secondly, it affirms former stereotypes of Asian Americans through re-asserting old characteristics associated with early Asian immigrants (Lee & Zhou, 2015, pp. 194-195). Beginning in the eighteenth century, the following characteristics were associated with Asian immigrants to the U.S: “alien”, “dangerous”, “docile”, “dirty”, “don’t speak English well”, “have accents”, “submissive”, “sneaky”, “stingy”, and “greedy” (Chou & Feagin, 2015, pp. 7-10). According to Robert G. Lee, an Asian American scholar who studies media portrayals of Asian Americans, the negative constructions associated with the “Oriental” can be divided into six image categories. These categories include, “the pollutant, the coolie, the deviant, the yellow peril, the model minority, and the gook” (Lee R. G., 1999, p. 8). Even though this imagery was first applied to Chinese immigrants who came to the U.S. in the 1800s, the same themes are prevalent in media representations of Asian Americans today. These images inform the ways that many White Americans come to understand Asian culture and determine how they view themselves in relation to Asian Americans. Through imagery that depicts Asian American men as weak, unmanly, and inferior, and White American men as strong, masculine, and superior, White men assert their dominance over Asian men (Espiritu, 2008, p. 9). Asian American women are considered docile, quiet, desperate, and eager to serve. In both representations, Asian American men and women are described through their inferior nature to White Americans. According to renowned Sociology Professor Patricia Hill Collins, “This system of oppression in turn is maintained by a set of ‘controlling images’ that provides the ideological justification for the economic exploitation and social oppression of Asian Americans” (Collins, 1991).

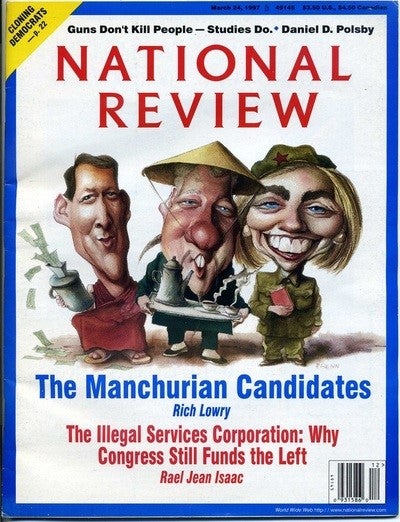

A poignant example of these hierarchical racial representations can be found on the cover of the National Review’s March 1997 edition. The National Review published a copy of their magazine depicting an emasculated Bill next to a buck-toothed-slanted-eyed Hillary Clinton. Other than putting a rice hat on Bill, increasing the size of their bucked teeth and trading in round eyes for almond ones, the publication did not have to do much to make their joke. Even though the subject of their ridicule was intended to be the Clintons, the mockingly stereotypical Asian caricatures made up the joke’s substance. After being confronted, the publication’s editor refused to apologize, and the story quickly lost traction outside of Asian American communities (Chou & Feagin, 2015, p. 11). This instance illustrates how Asian American discrimination is often invisible outside of Asian American circles.

Third, the model minority myth establishes external expectations of Asian American educational attainment and professional success. These expectations create an achievement paradox where Asian Americans are pressured into certain careers and behaviors (Le, 2007, p. 70). Unfortunately, these expectations have been linked to high rates of suicide and depression among Asian Americans, and especially among Asian American women (Chou & Feagin, 2015, p. 21). Due to racialized understandings of Asian Americans as social outcasts many mental health warning signs are overlooked. Stereotypes such as “Asians are good at math” pressure Asian Americans to work harder to meet these expectations as well as affirm that Asian Americans who do not fit in this frame are “bad Asians” (Lee & Zhou, 2015). Increased dropout rates of Asian Americans that fail to meet these standards are indicative of the negative influence that even positive stereotypes have on Asian American livelihood (Chou & Feagin, 2015).

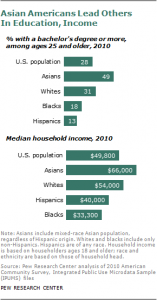

% with a bachelor’s degree or more, among ages 25 and older, 2010 (U.S. population: 28%, Asians: 49%, Whites: 31%, Blacks: 18%, Hispanics: 13%)

Median household income, 2010 (U.S. population: $49,800, Asians: $66,000, Whites: $54,000, Hispanics: $40,000, Blacks: $33,300)

Finally, the model minority myth justifies the argument that Asian Americans do not face racial discrimination and therefore should not be afforded the same benefits as other racial minority groups (Suzuki, 2002). This notion assumes that Asian Americans have the same experiences and fails to account for the wide achievement gaps that exist between Asian American subgroups. Statistics, like those displayed on the graph to the left, have been used to argue that Asian Americans no longer face discrimination and therefore should not receive benefits afforded to other minority groups. These arguments are justified through oversimplifications of statistics measuring socioeconomic indicators. Research institutions such as Pew released data that has been used to downplay the achievements of Asian Americans and rationalize discriminatory arguments aimed at them. (Hing, 2012).

The debate about affirmative action and the model minority’s role in it illuminates a theme prevalent throughout Asian Americans’ history in the United States: the consistent pitting of Asian Americans against other minority groups. Rather than using the same strategy that is employed towards Hispanic and Black groups in the U.S., Whites have held Asian Americans up as the exemplary minority race and model for successful assimilation into White America (Ng, Lee, & Pak, 2007). Asian Americans are deployed as part of the “pull yourself up by your bootstraps” mentality and as proof that the American Dream can be a reality even for minorities (Chou & Feagin, 2015, p. 13). Despite their incorporation into the Manifest Destiny narrative, Asian Americans also face the perpetual foreigner stereotype that describes the notion that Asian Americans are never fully American regardless of how long they have lived in the U.S., their level of achievement, and willingness to assimilate (Chou & Feagin, 2015, p. 17). This stereotype was codified into law in the 1922 Ozawa case when, “the Supreme Court ruled that Asian immigrants were not white and thus could not become citizens” (Chou & Feagin, 2015, p. 7).

Barriers to citizenship have been less pervasive since the mid to late twentieth century but the discriminatory treatment of Asian Americans has only changed form. The model minority stereotype is a new vehicle for older Asian stereotypes to be reintroduced. Asian Americans thus have a culture imposed upon them by White Americans expectations of how they should be (Chan, 1991, p. 81). Media representations of Asian Americans are one-dimensional and often portray them affirming popular positive and negative stereotypes. These stereotypes are not new, but simply rebranding of those that were associated with early Asian immigrants.

Groups Most Negatively Impacted

A history of the model minority stereotype would be incomplete without mention of changes to immigration trends for Asian Americans and the roles of hyper-selectivity and host-reception. Vietnamese and Chinese migration patterns are telling examples of how the model minority stereotype works for and against Asian subgroups differently. The differences between Chinese and Vietnamese migration patterns to the U.S can be traced to the relative representation of Chinese and Vietnamese American students in higher education (Lee & Zhou, 2015, p. 23). Data comparing Vietnamese and Chinese American relative degree attainment rates after migrating to the U.S. are far higher than their non-migrant counterparts. This means that both Chinese and Vietnamese Americans are highly selected, however only Chinese Americans are hyper selected.

The difference between highly selected and hyper selected is that highly selected only means that there is overrepresentation at the university level compared to the general population. In this case, Vietnamese Americans were not more likely than Whites to receive college degrees, while Chinese Americans were far more likely than Whites to receive college degrees (Chou & Feagin, 2015, p. 30). Returning to the racial hierarchy described above, where Blacks are at the unprivileged end and Whites are at the privileged, Chinese Americans would be closer to the White end of the spectrum, while Vietnamese Americans would be towards the Black end but above Blacks, Hispanics, and Native Americans. This is based on measurements of socioeconomic status and studies of White perceptions of Asian Americans (host reception) and their understandings of the veracity of racial stereotypes (Le, 2007, p. 59).

Since many anti-Asian stereotypes were based on early Chinese and Japanese immigrants to the U.S., they fail to accurately resemble the characteristics of south and southeast Asian Americans (Goodman & III, 2012). Unsurprisingly, China and Japan are more developed than many of their neighboring Asian countries and therefore the model minority stereotype based off their performance erases the very real achievement struggles that other Asian subgroups face (Museus & Kiang, 2009). More simply this means that many Asian Americans are struggling, and Americans have been conditioned to minimize that struggle or to overlook it entirely.

Gendered Stereotypes

As seen in the National Review cover above, Asian men and women are stereotyped differently. While both Asian American men and women are impacted by the model minority stereotype, this section of the paper will focus on its influence on women. According to a 2009 study conducted by the University of Washington, 16% of Asian American women born in the U.S. have contemplated suicide. This statistic is 3% higher than all other groups. The study also argued that Asian American women are more likely to attempt suicide in their lifetimes (Duldulao & Wang, 2009). Research investigating why Asian American woman are more prone to think about and attempt suicide, have pointed to achievement paradoxes created by the model minority myth (Duldulao & Wang, 2009) (Lee & Zhou, 2015). While there are studies that look at this problem, there have been issues with overestimating the role of culture in this process. For example, some research indicates that while Asian American women are overrepresented in terms of feeling suicidal, they rarely utilize mental health services (Duldulao & Wang, 2009). From ther scholars are left with trying to estimate the role that culture plays in that decision. Unfortunately, this usually results in overestimating the cultural influence or misinterpreting the culture all together. If some respondents report that they are skeptical of western medicine and therefore do not go to counseling, then there is an increased likelihood that that information would be taken to represent all Asian American women and reinforce cultural expectations onto their behavior.

Perhaps an answer to the high depression and suicide rates among Asian American women can be found in their history of assimilation. When Asian immigrant women first came to the United States they did so as a legal appendage of their male spouse (Espiritu, 2008). Since Asian people living in the U.S. did not qualify as citizens under the law, inhumane treatment of Asian women, like other women of color was normalized. At the same time that White women were being pushed out of their jobs and into the cult of domesticity, women of color were taking on longer days and more traditionally male positions in the workforce (Espiritu, 2008, p. 12). Asian men however had been demonized by white society during the post-World War II era. This emasculation also took the form of providing Asian women with the jobs that were formerly afforded to Asian men (11). The increasing status of Asian women’s work and decreasing status of Asian men’s work created gender instability in the household (13). Even though Asian women’s work recognition rose, they quickly became part of an overworked and underpaid exploited workforce. Asian women were held accountable for maintaining the household and they likely faced resentment from the men in their family despite still being taking advantage of by the industry. Asian American women face the double-jeopardy of being a woman and an ethnic/racial minority. Immigrant Asian women face the “triple-threat” of dealing with the aspects of double jeopardy on top of adapting to new gender roles both in American culture and in their household (Le, 2007, p. 71).

Today the model minority myth upholds that Asian American women have broken through the glass ceiling. While there is increased representation of Asian American women in high paying professions, they are still less likely to hold leadership positions. Asian Americans generally can access technical professions easily but are the last racial group to be thought of when it comes to leadership (Chan, 1991). Asian American women face this harsh reality even more so than Asian American men.

Theoretical Expectations

Using intersectional theories, this research design emphasizes the relationship between race and class to determine how the model minority stereotype impacts women from different Asian ethnicities. Based on existing model minority scholarship, it would be reasonable to expect women who identify as south or south east Asian to report feeling overlooked due to the model minority stereotype, and for women from developed Asian countries to feel less impacted by the model minority myth, but still report racial discrimination (Kim, 2012).

A study focusing on the respondents’ experiences with racial discrimination will hopefully result in increased information about what role those interactions have on the respondents’ role in society. Through asking questions about the nuances of those interactions and their perceived impact on the respondent, the goal is to augment existing quantitative research which qualitative explanations for interpreting data.

While a working hypothesis or expectation could be that Asian American women descending from less developed countries perceive being overlooked more by educational programs, the way the research design operates is somewhat antithetical to a hypothesis. This is because the goal is to deconstruct misinformation spread by the model minority stereotype. A challenge with that is determining what information about Asian American women is and is not accurate. To avoid falling into the same trap that the Pew Research Center study did, this paper focuses more on examining existing literature and studies and designing a study based on where the research is lacking.

Data & Research Design

The goal of this research design is to fill in some of the gaps created by the dissemination of the model minority stereotype. To do so it is first important to see where previous studies went wrong. According to the Asian American Center for Advancing Justice (AACAJ), in publishing the 2012 Pew study they, “paint a picture of Asian Americans as a model minority, having the highest income and educational attainment among racial groups. These portrayals are overly simplistic” (Hing, 2012). This research would need to focus on Asian American portrayals of their own lives versus the pervasive myths that depict how non-Asians imagine Asians to be. In other words, this paper aims to demystify how Asian Americans lives are, not how they are expected to be. Theories of Asian American assimilation, intersectional models, and missteps of previous studies all inform the sample interview questions. Through evaluating the correlating factors with the responses, the results will hopefully increase the accuracy of understanding the complexities of Asian American women’s identities.

Narrowing the scope of the research, this paper looks to Asian American women that are classified as middle-income in U.S. Census data. Additionally, these women will have applied to a Baccalaureate institution in the United States. The interview will include open ended questions that allow the interviewee to expand on their experiences and encourage them to share detailed accounts of their lives. For the sake of diversity this study would take place in Houston, Texas. Houston is one of the most diverse cities in the United States and it boasts a large Asian American population.

This research design will be instrumental in increasing research about Asian American women, but it will not do so without its own biases and limitations. Some Asian American groups will be overrepresented, and others will be underrepresented based on the qualifications stated above. Namely that the women will have applied to college and belong to the middle-class. Over one-third of Hmong, Cambodian and Laotian Americans living in the U.S. over the age of 25 do not have a high school degree. Furthermore, Laotian and Cambodian Americans report poverty rates higher than that of African Americans (Hing, 2012). This example illustrates how the study’s sample pool is already biased against these groups.

The reason that this study includes these narrowing characteristics is because it would be difficult to determine whether an Asian American student was afforded or denied access to educational programs based on their race or finances if they were considered financially disadvantaged. Asian American college applicants who belong to the middle class however are less likely to be afforded access to educational programs based on financial need. This model better isolates the variable of race for this study. Unlike previous accounts that focus on socioeconomic success as the primary indicator for Asian American quality of life, this study will attempt to delve into the nuances and complexities of Asian American women’s existence in the U.S.

Previous interviews have asked questions about social welfare programs but have paid less attention to the distribution of non-need-based educational programs among Asian American women. This study will in turn include a variety of questions that aim at discovering the distribution of these educational programs to Asian American as well as their implications. Some of these implications include how interviewees perceive being awarded or denied access to certain programs as well as how it impacted their self-perception. Through pairing questions with data collected about the respondents, the research is designed to reveal how the model minority stereotype shapes Asian American women’s self-perceptions and how their responses compare to the technical data collected about their lives.

The baseline number of questions will be fifty. This does not include the follow-up questions that the interviewer can ask. Since the goal of this study is to collect as much qualitative data as possible, it is willing to forgo strict formality in favor of more in-depth responses. Since the paper’s goal is to limit misinterpretation, collecting information in this manner increases the analysis of the interviewees responses as opposed to the interviewers questions.

Interview questions were written with the goal of thoroughness in mind. The following five questions (and theoretical follow-up questions) represent five themes that the study focuses on. The first is simply, “what was your first experience with the term ‘model minority’?” If the respondent indicates that they are not familiar with the term, then the interviewer would ask “what do you interpret the phrase ‘model minority’ to mean?” Upon informing the unfamiliar respondent of the definition of model minority, the interview would continue with questions about discrimination, such as, “have you ever faced racial discrimination?”, “please describe an encounter with racial discrimination”, and so on. The third theme aims to reveal the connection between the model minority stereotype and gender. A sample question for this theme is, “what role does gender play in the discriminatory encounters you described before? How do you feel these encounters shape the way that you view yourself today?” Hopefully these questions paired together are specific, yet vague enough to allow the respondent to discuss how they believe their experiences have been gendered. The fourth theme is about educational advancement. Questions in this section were motivated by the inequitable advancement of some Asian American subgroups over others when it comes to higher education. A sample of this questions is, “how did affirmative action benefit or disadvantage your education?” This question is especially open-ended because in previous studies, Asian American students have been quick to say that they do not benefit from affirmative action if they are Chinese American, Japanese American, or Korean American. Respondents who were Vietnamese American, Thai American, Cambodian American, Indian American and so on, were more likely to say that they did benefit from affirmative action (Museus & Kiang, 2009). This section is telling because the responses will likely vary the most. The final section is a straightforward section about mental health. Questions will look to gauging respondents’ awareness of Asian American women’s mental health struggles as well. One question would aim at awareness and another would aim at figuring out why Asian Americans are less likely to use mental health services.

Preliminary Conclusions & Contributions of the Research

If this study took place it would likely confirm what many of the other studies have concluded: that Asian American women from south and southeast Asian countries are often overlooked (Duldulao & Wang, 2009). This association is due to the assumptions propagated by the model minority stereotype. Women from different Asian subgroups would likely react differently to the model minority stereotypes based on whether they remotely apply to them. The term remotely is used to denote that the stereotype is by no means accurate, but it can be more representative of certain Asian American subgroups than others. Depending on the respondents’ ethnicity, education level, and perception of expectations created by the imposition of the model minority, the research will provide key insight into how Asian American women’s identities are influenced by the stereotype.

Conclusion

Even though this research design is hypothetical, the research collected in creating it reveals the complexities that researchers and Asian Americans alike face when confronting the model minority mythology. Through asking well thought out questions and consciously working to separate myth from reality in the conclusions, this study hopes to provide a more accurate understanding of Asian American women’s experiences through studying their access to educational programs. By denoting who is and perhaps more importantly, who is not considered part of this mythology, researchers will be able to create more accurate and positive images of Asian Americans living in the United States.

Taking control of how these images are informed and created is the first step to countering negative mythologies like the model minority. Through discovering how Asian American women view themselves, scholars can begin to debunk the myths that are associated with Asian American livelihood. Furthermore, increased attention to systemic racism that Asian American women face could reveal solutions to the very real concerns of increased depression and suicide among them. By evaluating the complex nature of Asian American livelihood and identity formation in the U.S., there is hope for research and imagery that represents Asian Americans as the complex and diverse collection of individuals that they are.

Works Cited

Chan, S. (1991). Asian Americans: An Interpretive History . Boston: Twayne Publishers.

Chou, R. S., & Feagin, J. R. (2015). The Myth of the Model Minority . Boulder: Paradigm Publishers.

Collins, P. H. (1991). Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Emplowerment. New York: Routledge.

Duldulao, A., & Wang, J. (2009, September 23). Asian-American Women More Likely to Attempt Suicide. (M. Martin, Interviewer)

Espiritu, Y. L. (2008). Asian American Women and Men Labor, Laws and Love. Plymouth: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.

Goodman, D. J., & III, B. W. (2012). New Perspectives on Racial Identity Development. In C. L. Wijeyesinghe, & B. W. Jackson III, Pedagogical Approaches to Teaching about Racial Identity (pp. 216-239). New York and London: New York University Press.

Hing, J. (2012, June 21). Asian Americans Respond to Pew: We’re Not Your Model Minority. Retrieved from ColorLines: https://www.colorlines.com/articles/asian-americans-respond-pew-were-not-your-model-minority

Kim, J. (2012). Asian American Racial Identity Development Theory. In C. L. Wijeyesinghe, & B. W. Jackson III, New Perspectives on Racial Identity Development (pp. 138-160). New York and London: New York University Press.

Le, C. N. (2007). Asian American Assimilation: Ethnicity, Immigration and Socioeconomic Attainment. Library of Congress.

Lee, J., & Zhou, M. (2015). The Asian American Achievement Paradox. New York City: Russell Sage Foundation.

Lee, R. G. (1999). Orientals: Asian Americans in Popular Culture. Philidelphia: Temple University Press.

Museus, S. D., & Kiang, P. N. (2009). Deconstructing the Model Minority Myth and How It Contributes to the Invisible Minority Reality in Higher Education Research. New Directions for Institutional Research, 5-15.

National Review. (1997, March). Retrieved from UNZ.org: https://www.unz.org/Pub/NationalRev/?View=Issues&Period=1997_03

Ng, J. C., Lee, S. S., & Pak, Y. K. (2007). Chapter 4: Contesting the Model Minority and Perpetual Foreigner Stereotypes — A Critical Review of Literature on Asian Americans in Education. Review of Research in Education, 95-103.

Pew Research Center. (2012, June 19). The Rise of Asian Americans. Retrieved from Pew Social Trends: http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2012/06/19/the-rise-of-asian-americans/

So, C. (2007). Economic Citizens: A Narrative of Asian American Visibility . Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Suzuki, B. (2002). Revisiting the Model Minority Stereotype: Implications for Student Affairs Practice and Higher Education. In M. McEwen, Working with Asian American College Students. San Francisco: Josey-Bass.