By Alex Knudson

The classical period brought many changes to Western Music. Gone were the days of thick and complex polyphonic textures(1). The new classical style instead focused on short periodic melodies(2). These melodies featured a light accompaniment that was meant to make the music more appealing to all nationalities thereby entertaining all listeners(3). One of the best examples of this light and entertaining music style is chamber music, particularly the string quartet. As noted in the Oxford New Grove Dictionary, “with the exception of the accompanied sonata, the quartet was probably the most widely cultivated genre of ‘chamber music’.”(4) The quartet epitomized the classical style of refined and nuanced music(5). The quartet was unique because, unlike in other musical genres, within the four-part string texture all four parts are equal and they interact intimately with each other(6), although absolute equality of the voices rarely exists in the very earliest quartets(7). When studying the rise of the string quartet, there is no composer more influential than Joseph Haydn.

Joseph Haydn (1732-1809) was one of the most influential composers in the 18th century. Known as the first of the “Viennese Classicists”(8), Haydn was a prolific composer in every musical genre: vocal works, concertos, orchestral music, etc. However, it was the string quartet where he made one of his greatest impacts on history. It has been said that out of all the works of Haydn, the string quartets are “the most faithful mirror of his human and artistic personality” because he began writing them at a young age and did not finish until late in his career(9). Known as the “father of the string quartet,”(10) Haydn’s impact on the genre has been felt by some of the most well known composers in history, such as Mozart, Beethoven, and Shostakovich.

There are many evidences pointing to Haydn being the father of the string quartet. Oddly enough, being the first to write a string quartet is not one of them. Haydn had other contemporaries who also were writing music for this genre. Franz Xavier Richter and Ignaz Holzbauer each wrote quartets and possibly could have written them before Haydn ever attempted his first quartet(11). Alessandro Scarlatti wrote a set of six works he called “Sonata a Quattro per Due Violini, Violette e Violoncello senza Cembalo,” which roughly translates to “Quartet for two violins, viola, and cello without keyboard.” Some speculate that Scarlatti’s output was a precursor to the string quartet although no real evidence to that claim exists because the instrumentation he used was commonly used in symphonies and other sonatas at the time(12). If Haydn clearly wasn’t the first to write a string quartet, why is it then that he is considered its originator? I believe that he is considered the true ‘father of the string quartet’ based on his output, his establishment of structure and form, and for his impact on later composers.

Upon examining his output, the number of quartets Haydn produced is unequaled. Mozart would eventually write a respectable 26 quartets(13) while Beethoven wrote 16 of his own(14). Xavier Richter, one of Haydn’s contemporaries, wrote 6 pieces that were later published as his string quartets(15). To put that in perspective, Haydn wrote 68 string quartets, over ten times more than Xavier Richter and nearly triple that of Mozart and Beethoven(16). Haydn’s musical output was astonishing and unmatched by any of his peers. For this reason alone we could consider Haydn the Father of the String Quartet.

Yet it is not only the musical output that gives him this title but rather, the quality of all his works. By somewhat standardizing the quartet structure, Haydn was able to produce an incredible number of quartets without sacrificing quality. One researcher described Haydn’s style saying that the quartets he created were “multifunctional masterpieces which offer pleasure for the performer and the audience but also a sophisticated ‘essay’ in composition for the connoisseur reader.”(17) This quality was achieved partially by the instrumentation of the string quartet. As stated in the name, there are four players: two violins, one viola, and one cello. Perhaps equally as important as the number of players is the fact that all four of them play string instruments. By making all four musicians string players, Haydn created a homogenous sonority that promoted a unity of sound(18).

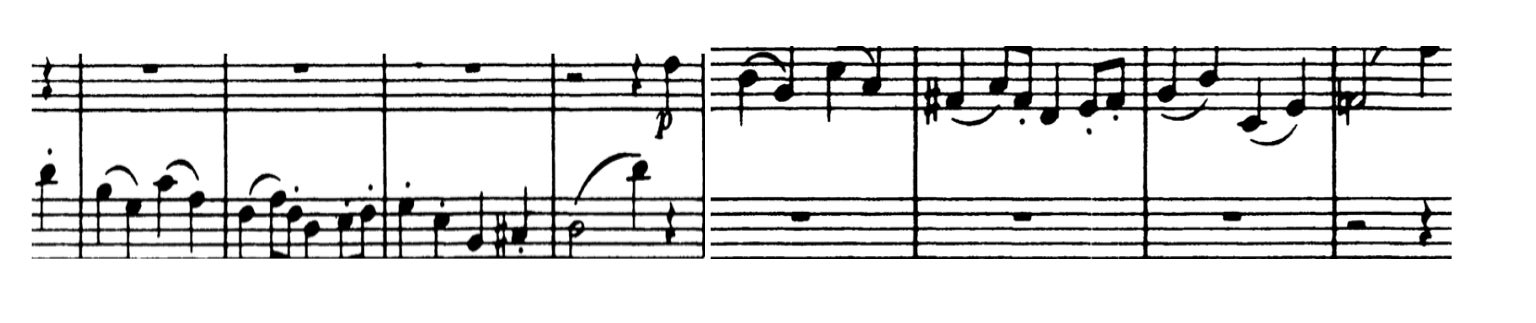

Another way Haydn molded the string quartet was to embrace the classical style(19) and write short periodic melodies with the other three parts lightly accompanying the melody. Generally, this melody was given to the first violin while the rest of the group accompanied. This was largely because the first violin was usually considered the leader of the amateur group of players(20). Another reason the violin was given the melody was that by adding the melody to the highest sounding sonority, it stabilized the tonal center of the quartet and the contrast between high and low sonorities made it very clear which part had the melodic material(21). An example of a short periodic melody can be found in the first violin part of Haydn’s String quartet in D major “the Lark” Op. 64 No. 5 as pictured below.

As seen here the melody begins with a short four-measure phrase and then is answered with a second four-measure phrase creating a short melody in an eight-measure period.

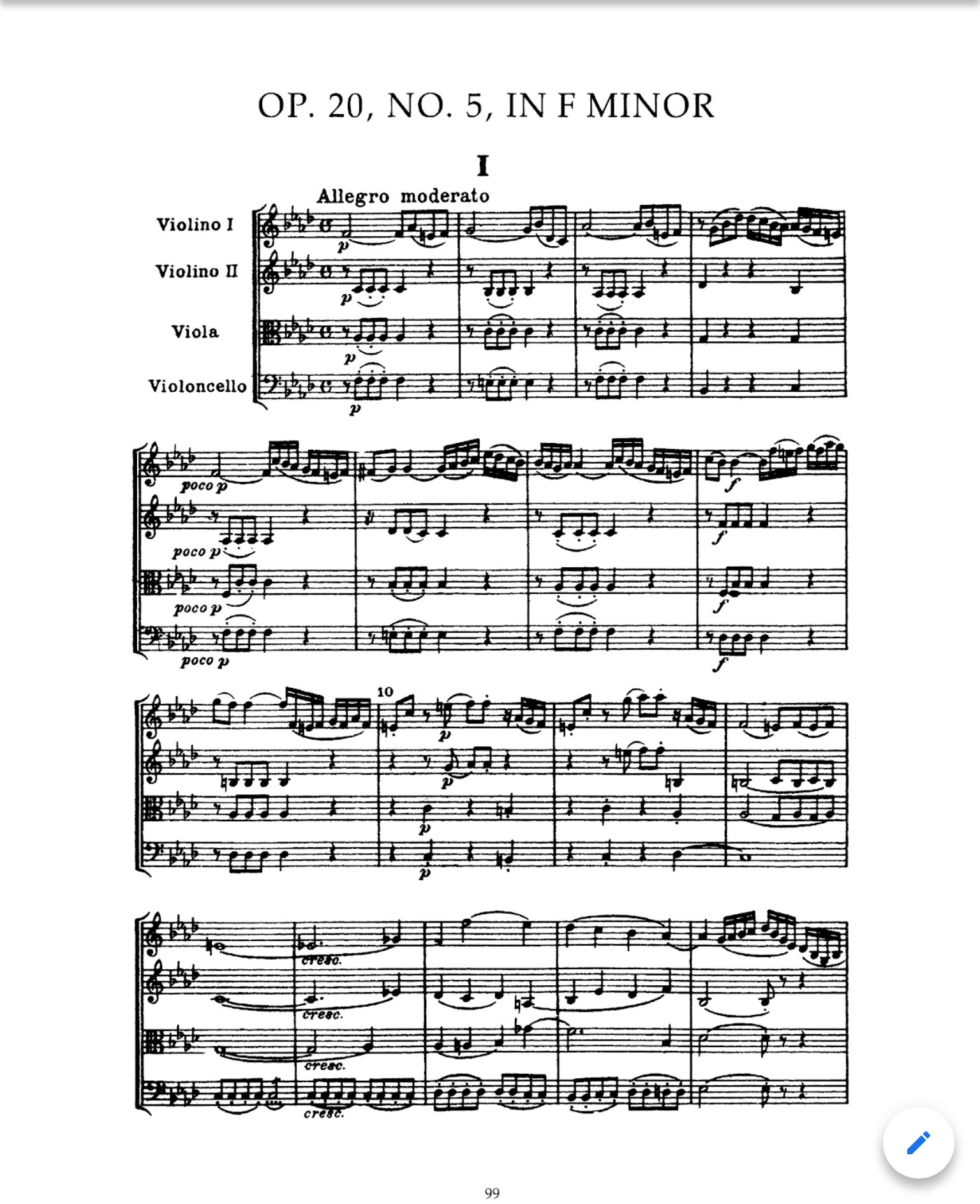

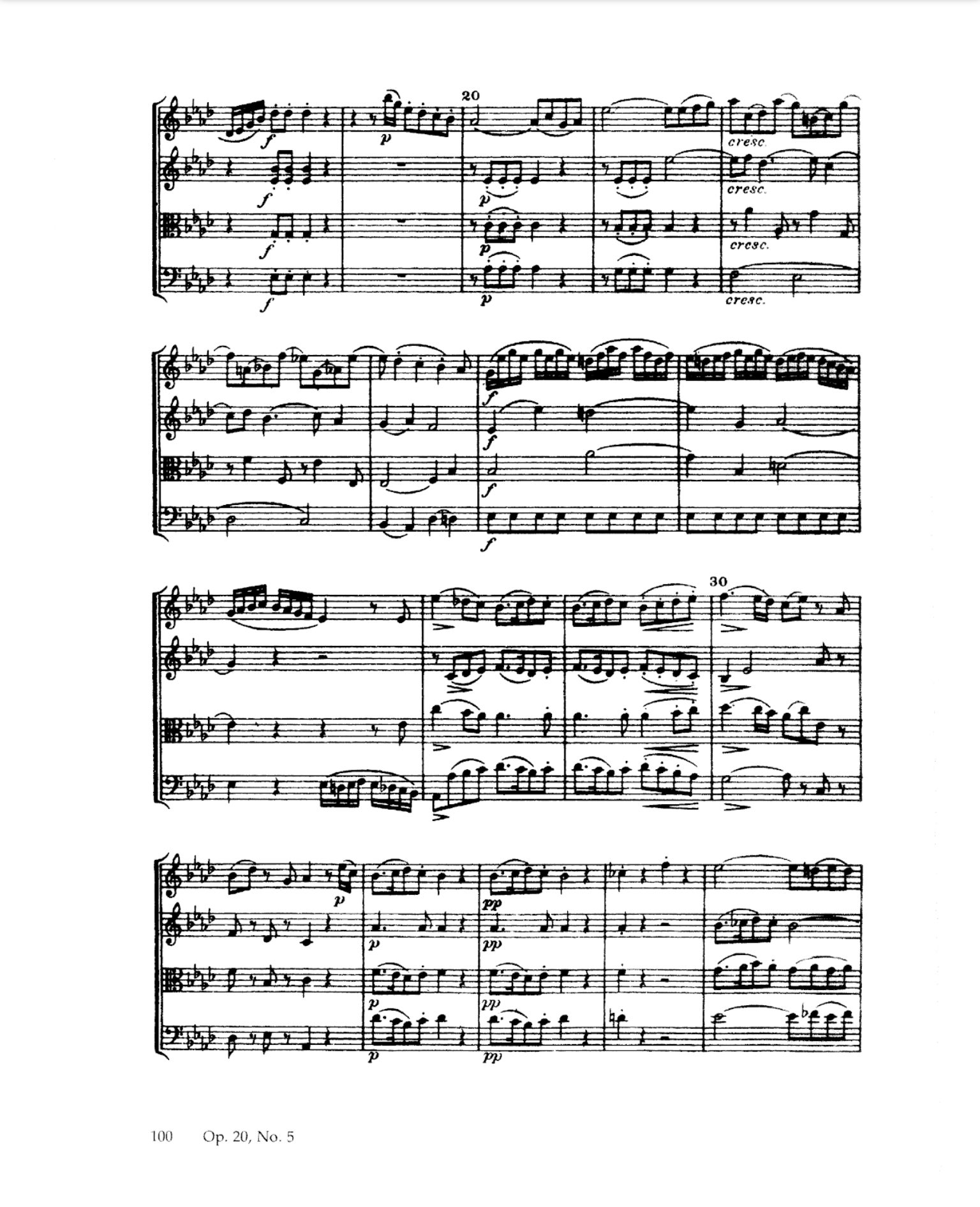

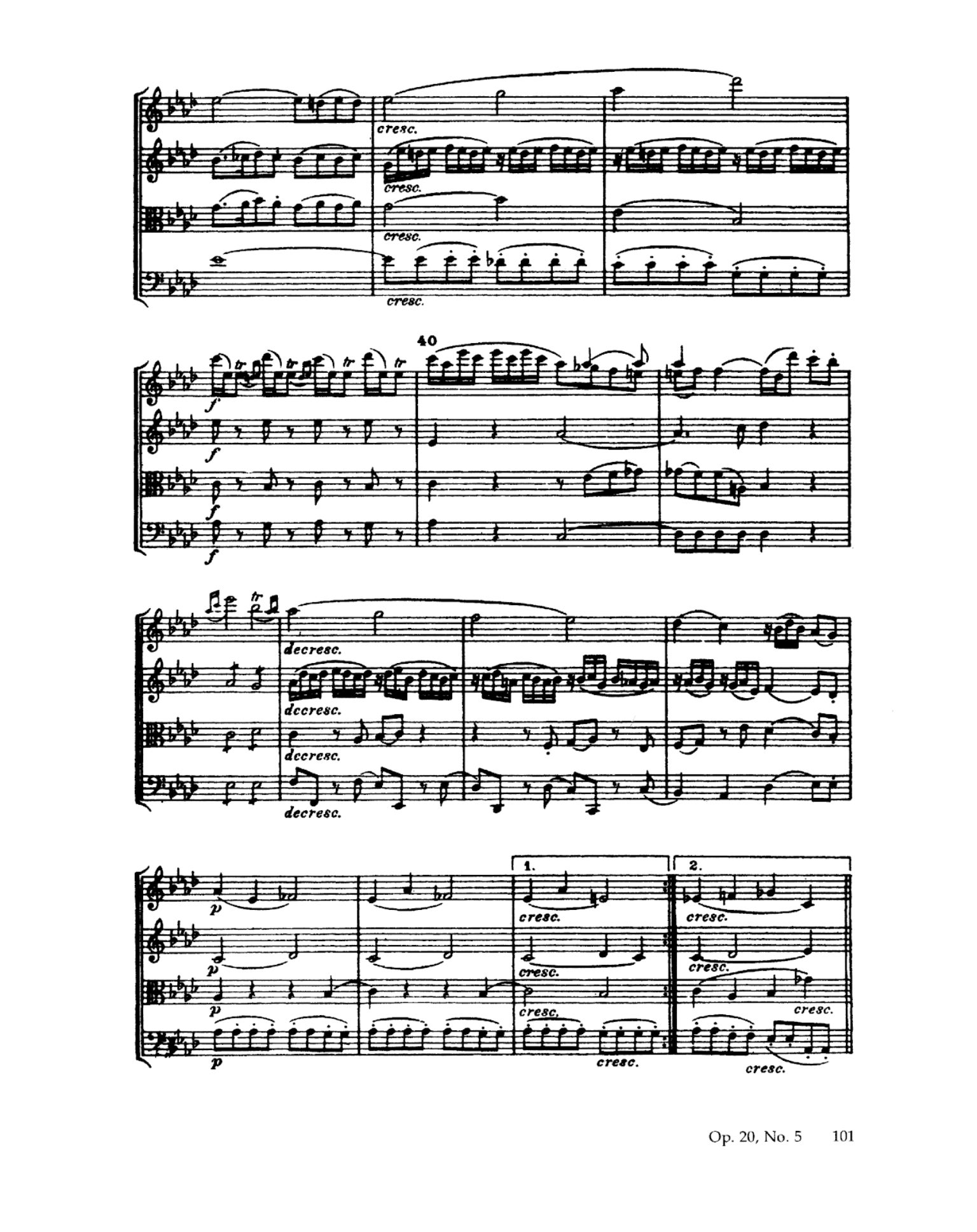

Reviews written of performances of Haydn’s quartets often only mentioned the 1st violinist’s name, further illustrating the fact that the quartets were written with the 1st violin playing the melody during the majority, if not the entire time(22). An example of this technique of using light accompaniment to compliment the continuous melody can be found in the first movement of Haydn’s Quartet in F minor, Op. 20 No. 5 located in the appendix of this paper. Looking at this movement one can see that while the first violin has an elaborate melodic line, the other three voices play repetitive sequences of simple accompaniment. This style was common throughout all of Haydn’s quartets and was a staple of the classical style.

Later in his life, Haydn did not limit the melody to the violins in his string quartets, rather he allowed the other parts, such as the cello, to play it as well. His signature structure of light accompaniment to go with the melody continued, but the melody was placed in different voices. One researcher described this interaction of melody in different voices as a “polite conversation.”(23) This could be where Beethoven, Mozart, and other later composers got the idea to give the other voices more melodies. An example of the melody being in another voice can be found in Haydn’s Quartet Op. 76 No. 1.

As noted in the score, after using three chords to establish the key, the cello then introduces the theme which is answered by the viola creating a eight-measure period out of two four-measure phrases. Although the melody is in the different voices the same rules still apply that the melody is short and periodic thus continuing the style that Haydn established with his previous quartets.

Besides the structure of the phrases, Haydn also standardized the formal structure of the movements of the quartet. When Haydn first attempted to write quartets, sometime between 1755-1760, he called them divertimentos(24). These early quartet works were unique in the sense that they contained five movements instead of adhering to what is now considered as the traditional four-movement quartet normally expected. It was some time before he wrote another quartet. However, around 1768-1770 he finally attempted a new set of quartets, titled Op. 9, and in them he used the four-movement quartet form(25). This new form would stick and he followed this structure for the remainder of his quartets.

In the four-movement quartet form standardized by Haydn, each movement had certain assigned characteristics regarding tempo. Beginning with the 1st movement, Haydn used the form that had been used in sonatas, symphonies, trios and other multi-movement musical works: the sonata form(26). The sonata form with its exposition, development, and recapitulation, provided Haydn with the structure that he needed to explore thematic invention, elaboration, and structural intrigue within the movement(27). Said one researcher, “the commanding presence of sonata forms in the quartets points to their central importance for Haydn’s concept of the genre and its possibilities.”(28) This sonata form was typically marked as allegro and allowed Haydn to introduce his primary theme and then toy with that theme throughout the movement thus creating a thematic unity in the movement(29). Evidences of this thematic unity can be found in Haydn’s earlier Quartets Op. 9 and Op. 17(30).

The order of the second and third movements of the quartets was often interchangeable(31). They included a dance movement and a slow song like movement(32). The dance movement was intended to be a minuet in triple meter(33) although other quartets such as the six quartets of Op. 33 were marked with the term scherzo or scherzando which simply meant to play the movement lightly and cheerfully(34). The minuets were tuneful and lighthearted which was helpful in contrasting the seriousness and slow tempo of the other inner movement(35).

The slow movement was filled with contrast to the other movements in the quartet. Often they contained a theme and variations as well(36). Unlike the fast lively tempos of the 1st movement sonata form and the 2nd or 3rd movement dance forms, the slow movement allowed Haydn to express a more serious emotion. In his Op. 20 No. 2, the slow movement was described as containing “the passion behind the darkly imaginative operatic-scena-without-words.”(37) By adding a theme and variations to the slow movements, each instrument is given a chance to shine which created the idea of a musical conversation occurring between the voices(38). The two inner movements became standard for the string quartet genre.

The final movement of Haydn’s quartets often contained different forms. A common form used was the rondo form. This form was favored by Haydn because it contained repeating expressions of the original theme(39). Other forms that Haydn used in the final movement of his quartets include rondo, sonata allegro, and irregular forms containing fugal procedures(40). The one constant throughout the final movements is the use of tempo. The quartets always ended with a bright brisk allegro or presto tempo.

The forms and voicing Haydn used in his quartets became the standard to follow for generations to come. Apart from interchanging the two inner movements in the quartet, the standard four-movement form was followed very strictly by Haydn and set the example for all future composers of the genre(41). Numerous composers, from Mozart and Beethoven to Bartok and Shostakovich, used these forms and added their own personal flairs by adding extra movements or by mixing the melody and phrasing throughout all the voices.

Mozart was one of these composers who admired and emulated Haydn. This is evident in the six string quartets that Mozart wrote and dedicated specifically to Haydn. The purpose of these quartets was to imitate and praise the style of Haydn’s quartets while still adding his own personal touch(42). Mozart’s quartets have textures that are very similar to those of Haydn with all four parts supporting the main musical idea. Just as with Haydn’s quartets, this technique serves to integrate and unify all four voices of the quartet(43).

Beethoven too was greatly influenced by the genius of Haydn. Beethoven’s early quartets, such as the set of six Op. 18 quartets, were written in the style laid out by Haydn: the traditional four-movement quartet that was easy to listen to and universally entertaining(44). Even as Beethoven continued to develop and expand on the quartet structure previously laid out by Haydn, the influence of Haydn was still present in his quartets. An excellent example of Haydn’s influence is Beethoven’s last string quartet. Unlike his other late quartets, which include more than four movements as well as elaborate fugues, Op. 135 seems to mimic the classical style established by Haydn. Early researchers of this topic seem to agree that indeed it was purposely written this way as a sort of “homage to Haydn.” Later researchers have also agreed stating “the last quartet is a brilliant study in Classical Nostalgia.”(45)

Through examination of his works and impact on fellow composers, it is evident that Haydn was the master and founder of the string quartet genre. The incredible amount of musical output was unique and unrivaled by any of his contemporaries and later composers. He was able to take an instrumentation that had not been used often and really develop and push it to its limits. His legacy and historical impact is evident in the popularity and rise of the string quartet from the time he wrote his first quartet to the present day. By standardizing the four-movement form of the quartet and keeping his melodies short and periodic, he embraced the classical style(46) and became the true father of the string quartet.

Notes

- Peter Burkholder, Donald Jay Grout, and Claude V. Palisca, A History of Western Music (New York: W.W. Norton & Company), 469

- Burkholder, Grout, and Palisca, A history of western music, 462

- Ibid., 469

- Cliff Eisen et. Al, “String Quartet.” Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. Accessed November 25, 2016. http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/subscriber/article/grove/music/40899

- Eisen et. Al, “String Quartet.”

- Rosemary Hughes, Haydn String Quartets (London: The Garden City Press Limited, 1966), 5

- Floyd Grave and Margaret Grave, The String Quartets of Joseph Haydn (New York: Oxford University Press, 2006), 26

- James Webster and Georg Feder. “§11: Chamber music without keyboard.” Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. Accessed November 25, 2016. http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/subscriber/article/grove/music/44593pg11

- Hughes, Haydn String Quartets, 5

- Webster and Feder. “§11: Chamber music without keyboard.” Grove Music Online

- Grave and Grave, The String Quartets of Joseph Haydn, 10

- Robin Stowell et. al., The Cambridge Companion to the String Quartet. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 178

- Eisen, Cliff et. al., “Mozart.” Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. Accessed November 25, 2016. http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/subscriber/article/grove/music/40258pg3

- Joseph Kerman, Alan Tyson, and Scott G. Burnham, “Beethoven, Ludwig Van” Grove Music Online, Oxford Music Online, (Oxford University Press), accessed October 16, 2016 http://www.oxfordmusiconline/subscriber/article/grove/music/40026pg17

- Grave and Grave, The String Quartets of Joseph Haydn, 10

- Webster and Feder. “§11: Chamber music without keyboard.” Grove Music Online

- Lazlo Somfai,”…they are Full of Invention, Fire, Good Taste, and New Effects”: Two Compositional Essays in the “Erdody” Quartets Op. 76.” Studia Musicologica – Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 51 (2010) (3-4): 317-324

- Grave and Grave, The String Quartets of Joseph Haydn, 22

- Burkholder, Grout, and Palisca, A history of western music, 468

- Grave and Grave, The String Quartets of Joseph Haydn, 35

- Ibid

- Mary Hunter, “’the most Interesting Genre of Music’: Performance, Sociability and Meaning in the Classical String Quartet, 1800-1830.”Nineteenth-Century Music Review 9 (1): 53-74

- Grave and Grave, The String Quartets of Joseph Haydn, 36

- Ibid., 19

- Grave and Grave, The String Quartets of Joseph Haydn, 23

- Ibid., 49

- Ibid., 50

- Ibid

- Hughes, Haydn String Quartets, 29

- Ibid

- Grave and Grave, The String Quartets of Joseph Haydn,76

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Hughes, Haydn String Quartets, 30

- Burkholder, Grout, and Palisca, A history of western music, 534-535

- Hughes, Haydn String Quartets, 25

- Ibid

- Burkholder, Grout, and Palisca, A history of western music, 535

- Grave and Grave, The String Quartets of Joseph Haydn,121

- Ibid., 121-125

- Grave and Grave, The String Quartets of Joseph Haydn, 23

- Eisen, et. al., “Mozart.” Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online

- Ibid

- Kerman et. al., “Beethoven, Ludwig Van” Grove Music Online, Oxford Music Online

- Joseph Kerman, Alan Tyson, and Scott G. Burnham, “Beethoven, Ludwig Van, §17: Late-period works”, Grove Music Online, Oxford Music Online, (Oxford University Press), accessed October 16, 2016 http://www.oxfordmusiconline/subscriber/article/grove/music/40026pg17

- Burkholder, Grout, and Palisca, A history of western music, 468

Appendix

Bibliograpahy

Bakulina, Olga Ellen. 2012. “The Loosening Role of Polyphony: Texture and Formal Functions in Mozart’s “Haydn” Quartets.” Intersections 32 (1-2): 7-42. http://libproxy.boisestate.edu/login?url=http://search.proquest.com.libproxy.boisestate.edu/docview/1514321879?accountid=9649

Burkholder, J. Peter, Donald Jay Grout, and Claude V. Palisca. A History of Western Music. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2014

Eisen, Cliff, Eva Rieger, Stanley Saide, Rudolph Angermüller, C.B. Oldman, William Stafford. “Mozart.” Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. Accessed November 25, 2016. http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/subscriber/article/grove/music/40258pg3.

Eisen, Cliff, Antonio Baldassarre and Paul Griffiths. “String Quartet.” Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. Accessed November 25, 2016. http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/subscriber/article/grove/music/40899.

Grant, Roger Mathew. 2010. “Haydn, Meter, and Listening in Transition.” Studia Musicologica – Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 51, no. 1-2: 141-152, http://libproxy.boisestate.edu/login?url=http://search.proquest.com.libproxy.boisestate.edu/docview/821023859?accountid=9649.

Grave, Floyd and Margaret Grave. The String Quartets of Joseph Haydn. New York: Oxford University Press, 2006.

Hughes, Rosemary. Haydn String Quartets. London: The Garden City Press Limited, 1966.

Hunter, Mary. 2012. “the most Interesting Genre of Music”: Performance, Sociability and Meaning in the Classical String Quartet, 1800-1830.”Nineteenth-Century Music Review 9 (1): 53-74. http://libproxy.boisestate.edu/login?url=http://search.proquest.com.libproxy.boisestate.edu/docview/1317916016?accountid=9649.

Keller, Hans. The Great Haydn Quartets. [1986] New York: George Braziller, Inc., 1986.

Kerman, Joseph, Alan Tyson, Scott G. Burnham, Douglas Johnson, and William Drabkin. “Beethoven, Ludwig van.” Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. Accessed November 15, 2016. http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/subscriber/article/grove/music/40026pg13

Somfai, Lá. 2010. “”…they are Full of Invention, Fire, Good Taste, and New Effects”: Two Compositional Essays in the “Erdody” Quartets Op. 76.” Studia Musicologica – Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 51 (3-4): 317-324. http://libproxy.boisestate.edu/login?url=http://search.proquest.com.libproxy.boisestate.edu/docview/878607376?accountid=9649.

Stowell, Robin, David Wyn Jones, and W. Dean Sutcliffe. The Cambridge Companion to the String Quartet. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

Webster, James and Georg Feder. “§11: Chamber music without keyboard.” Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. Accessed November 25, 2016. http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/subscriber/article/grove/music/44593pg11