On a fall day in 2018, Dr. Uwe Reischl’s students examined the contents of an American Red Cross Emergency Preparedness Kit—and then they asked him if they could try making something better.

The American Red Cross, FEMA, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention encourage everyone to have a 72-hour emergency preparedness kit, also known as a “go-bag.” At a minimum, the bags include survival necessities like food and water, and other helpful items like a hand-powered radio, a flashlight, batteries, and a first-aid kit.

In addition to providing a checklist to help you build your own bag, the Red Cross sells ready-made kits. But the students in Reischl’s Disaster Preparedness Planning class saw room for improvement.

“It was supposed to be for a family of four but they didn’t provide any feminine hygiene products,” recalled student DaNae Snyder. Other contents, like the meal bars, seemed easy to replace with something better. “The food was a hard brick,” said student Kodi Romero, adding with a laugh, “we thought it was a fire starter.”

The Red Cross four-person kits currently retail at $286.18—another sticking point for the students. “If you expect people to have a 72-hour kit, you have to make it affordable for families,” said Snyder. “We thought we could do this—make it affordable, and add stuff to it that could really be utilized.”

The Public Health and Population Science course examines disaster preparation with a public health lens: students learn about risk management, community resources, and resilience. Reischl also challenges students to think outside of the immediate needs of food, water, and shelter in a large-scale disaster situation, and to also consider the importance of creating resources that provide elements of comfort.

The 2018 wildfires that devastated the community of Paradise, California made the course topic and their projects that much more real for the students. “It hit pretty close to home,” said Snyder. “It made you feel like what would you do? Where would you go?”

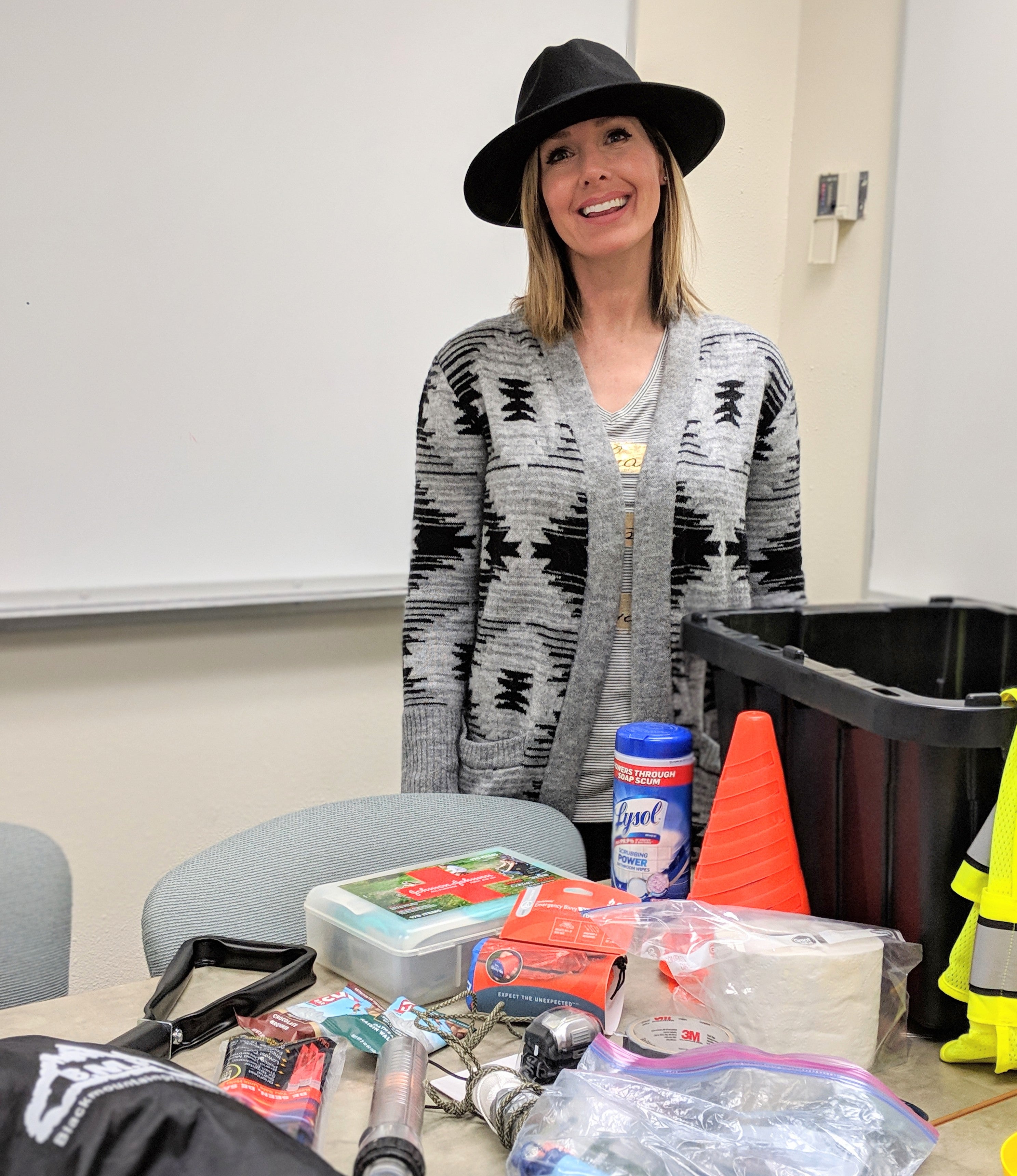

Reischl consented to the additional class project, and the students went to work building a set of emergency preparedness kits for a family. They presented the emergency kits at the end of the semester along with their original final project—3D models of emergency shelters—for an audience of faculty and public health professionals.

What did the students do differently?

Rather than including everything in one bag, the students made individual bags for each family member, distributing supplies and weight more evenly. They were able to match all of the essentials provided in the Red Cross 72-hour kit, and include elements that provided comfort and stress relief. They sourced many items at discount and thrift stores

“In a situation where a family is devastated by a fire, hurricane, or whatever the situation, it’s important to create a sense of normalcy. For a child, a blanket and a teddy bear can be very comforting,” said Snyder. They also included a coloring book and crayons for the kids, and for adults, a sudoku puzzle. “It could definitely come in handy for a distraction,” said student Nikole O’Neil.

In lieu of meal bars, the student-made bags incorporated foods like tuna packets, applesauce, and mixed nuts. The students were also sure to include feminine hygiene products and multipurpose items like baby wipes.

As for cost savings: “We spent $164 and had extra supplies left over,” said Snyder. That’s $120 less than the family-sized Red Cross kit.

Reischl’s class made a lasting impact on Snyder, who built her own 72-hour kit, and is convinced that everyone else should, too. “During a major disaster, you can’t count on the government to have the resources to meet everyone’s needs.”

Snyder recommends starting by assembling a one-day emergency supply and then increasing up to a 72-hour supply. “If we can think small at first and then build upon the 24-hour survival kit, it doesn’t seem as overwhelming.“

Ready to build your own 72-hour kit? Get tips and guidelines from FEMA, the American Red Cross and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. And don’t forget to add a few elements of comfort.

For a hands-on, in-depth study of the public health approach to disaster preparedness planning, students can also sign up for Reischl’s class: MHLTHSCI 560. He will be teaching it again fall of 2020.