Central District Health Opioid Settlement Fund Environmental Scan

Report Authors

- McAllister Hall, Research Associate

- Hannah Lang, Research Associate

- Kristi Spalding, Research Assistant

- Libbie Luevanos, Research Assistant

- Vanessa Fry, Director

This report was prepared by Idaho Policy Institute at Boise State University and commissioned by Central District Health.

Recommended citation: Hall, M., Lang, H., Spalding, K., Luevanos, L., & Fry, V. (2025). Central District Health Opioid Settlement Fund Environmental Scan. Idaho Policy Institute. Boise, ID: Boise State University.

Download a printable pdf of this report

Executive Summary

Central District Health (CDH) commissioned this environmental scan to better understand how jurisdictions within its service area — Ada, Boise, Elmore, and Valley Counties — are using Idaho’s opioid settlement funds, with the goals of informing strategic regional planning, reducing opioid-related harms, and protecting and promoting health in the communities that CDH serves. This report provides a comprehensive analysis of current opioid-related programming, identifies gaps in resources, unmet needs, and other actionable recommendations. Recommendations align with state-approved abatement strategies, as found in Exhibit A: Approved Opioid Abatement Strategies in the Idaho Opioid Settlement Intrastate Allocation Agreement), and CDH’s core values: Excellence, Positive Impact, Partnership, Innovation, Credibility and Humanity.

The project team from the Idaho Policy Institute (IPI) used a mixed-methods approach, including a review of publicly available data, six stakeholder interviews, and 12 focus groups involving 68 participants, including individuals with lived experience, service providers, and community partners. Quantitative data highlighted increasing overdose deaths and rising service demands, particularly in rural areas with limited treatment infrastructure. Qualitative findings revealed challenges such as barriers to detox and treatment services, lack of transportation, affordable housing shortages, and barriers to accessing clear information about available resources.

Key recommendations include:

- Establishing a regional steering committee to guide funding decisions and ensure alignment with local needs;

- Scaling effective harm reduction, transportation, and prevention programs;

- Expanding access to secular recovery models and detox centers;

- Enhancing cross-system partnerships for housing, reentry, and behavioral health services;

- Creating multilingual, accessible resource directories for community use.

This report will inform CDH’s five-year action plan for investing settlement funds, responding to community-identified needs, and fostering a more coordinated and resilient regional approach to opioid prevention, treatment, and recovery.

Return to the beginning of the report

Introduction

The opioid epidemic continues to pose a significant public health challenge across the nation. In Idaho, health districts have taken a role in addressing the crisis. Central District Health (CDH) has committed to advancing coordinated, data-informed solutions to address the crisis at the regional level. In alignment with approved opioid abatement strategies, CDH commissioned this environmental scan to better understand how cities and counties within its service area — Ada, Boise, Elmore, and Valley Counties — are using, or planning to use, opioid settlement funds.

This report represents a critical step toward regional alignment and strategic investment. It provides an overview of current opioid-related programming, identifies existing service gaps and community needs, and assesses funding strategies among settlement recipients. Drawing from both quantitative data sources and qualitative insights from stakeholders and key informants, this report offers a comprehensive picture of the region’s opioid response landscape.

The findings culminate in a set of actionable recommendations designed to enhance impact, reduce harms associated with opioid use, and guide future funding decisions. Rooted in collaboration and a commitment to community well-being, this report seeks to empower CDH and its partners with a shared vision for creation of evidence-based roadmap for the next five years.

Methodology

To complete this environmental scan, IPI used qualitative data obtained through engaging stakeholders and key informants as well as publicly available secondary data to guide their research. IPI focused on collecting data from the counties served by CDH.

Key informant interviews and stakeholder focus groups were used to capture the voices of the community. IPI worked with CDH to create question protocols that addressed the needs for the project. CDH assisted with recruitment by providing contact information for service providers, connecting focus group facilitators at IPI to community champions, and distributing recruitment materials.

IPI first attempted to facilitate focus groups in public spaces such as libraries and did recruitment through fliers disseminated by stakeholders. Most of these focus groups had no participants. As a result, IPI shifted the engagement strategy. Focus groups were planned to occur in places where key informants were already gathering, such as crisis centers and homeless shelters and then contacts at these spaces recruited people to participate. A $25 gift card was offered to all participants of the focus groups as an incentive for participation. All participants were asked but not required to provide their ages, gender, and other relevant demographic information. This information helped IPI determine if all populations were being reached. More details are provided in the focus group section of the report. Toward the end of the data collection, a survey version of the focus group protocol was sent to service providers to try to get more of their perspectives in the data. IPI conducted twelve focus groups with 68 total participants and received four survey responses.

CDH also wanted to hear from the municipalities and organizations that receive opioid settlement funds. There was an initial meeting led by CDH to bring these representatives together and discuss how funds have been used and any barriers to use. IPI attended this meeting and used it to inform their research. IPI additionally interviewed six people from cities and counties in the CDH service area to learn specific details about past, current, and future spending.

Data from focus groups and interviews was coded to identify themes relevant to research questions. IPI read through responses and created simple summaries for each. These simple summaries allowed for identification of commonalities across responses.

Secondary data was collected through a variety of reliable sources to create a foundational understanding of the current and historical state of opioid use and misuse in counties served by Central District Health. This data was gathered from sources such as the Idaho Department of Health and Welfare (IDHW), Idaho State Police (ISP), and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Return to the beginning of the report

Opioid Use or Misuse

Many organizations already collect data about opioid use, much of it is reported at the state or health district level. The use and misuse of opioids is difficult to measure, but there are some metrics that provide insight to the prevalence of opioid use.

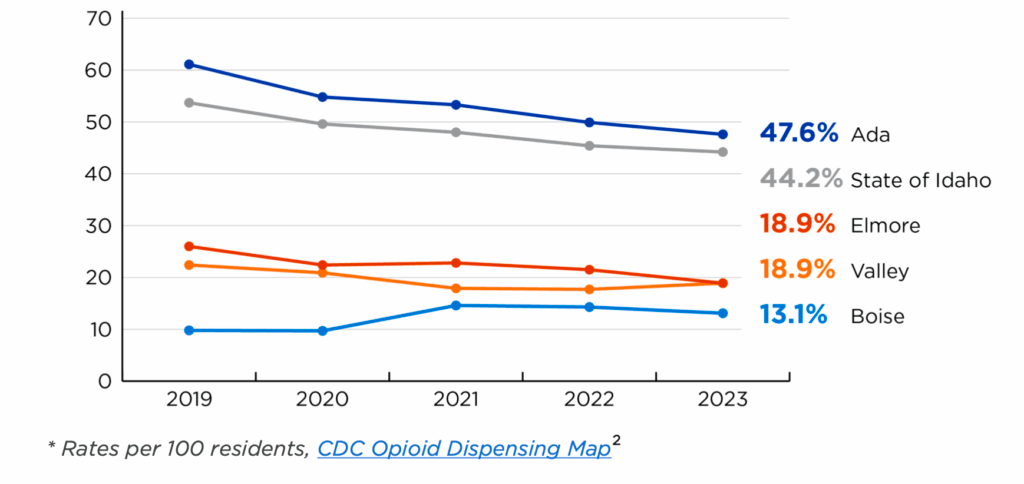

Opioid dispensing rates measure the number of retail pharmacy dispensed opioid prescriptions per 100 persons.1 Prescriptions are not the leading cause of overdoses but they do contribute to the amount of opioid related deaths. According to data from the CDC, Ada County dispensing rates have been dropping gradually since 2019 while the smaller counties have varied, but rates have remained low, especially compared to the statewide average. Ada County ranks between ten and twelve among counties statewide each year. It appears most counties are lowering their dispensing rates but very slowly.

Figure 1: Opioid Dispensing Rates Over Time

Another way to understand opioid use is to examine the use of detox and substance use services. Clarvida Crisis Center, formally Pathways, does not provide detox services but does provide evaluations that can refer patients to detox services. In fiscal year July 2021- June 22, 24% (270) of their admitted patients presented with issues with detox or sobriety. In the 2023-24 fiscal year, 91 clients were referred to a detox facility, compared to 62 in fiscal year 2022-23. Future data will be needed to understand if this increase will become a trend.

Allumbaugh House provides detox and substance use services in the Treasure Valley. They “accept all patients, including those uninsured and with Medicaid.”3 Since 2020, they have provided services to 700-800 patients each year and almost all of their patients (96-98%) receive detox services. Allumbaugh House is one of the few facilities providing detox services in CDH counties. The cost of detox services is increasing at Allumbaugh House. In 2023, it cost about $700 per day for a patient, a $100 per day increase from 2020. The price of detox services could dissuade some people with substance use disorders from seeking help.

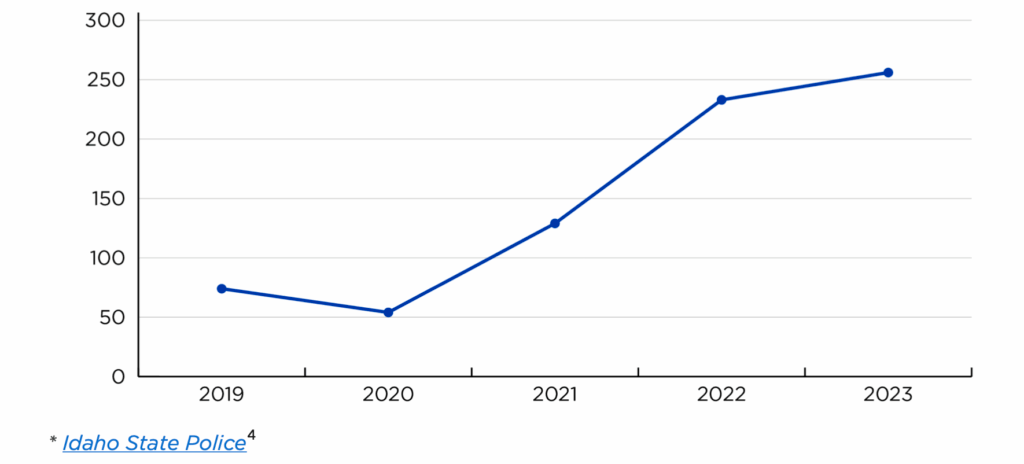

Crime data from ISP can also provide an idea of drug use patterns in an area. The amount of narcotic related arrests in CDH counties tripled from 2019 to 2023. Narcotics in this data refers to all opioids other than heroin and includes fentanyl. Though the reason for this increase is unknown, it could be the result of a general increase of narcotic use or police could have received training that has increased their ability to identify narcotic use and trafficking. In 2023, CDH counties had the second highest number of narcotics arrests compared to other public health districts in the state.

Figure 2: Number of Narcotic Arrests in CDH Over Time

Narcotic arrests include any arrests made in relation to drug seizures. ISP also reports on the amount of drugs seized (Table 1). This data could provide insight on the supply in the area. Seizure amounts vary by year and are very low in Boise and Valley Counties. There does not seem to be a pattern of increase or decrease.

Table 1: Number of Narcotic Drug Units Seized by County by Year

| Year | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ada County | 2,821 | 504 | 1,136 | 24,007 | 1,525 | 1,778 |

| Boise County | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Elmore County | 31 | 93 | 16 | 170 | 535 | 90 |

| Valley County | 0 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

* Idaho State Police5

Ada County is designated as a High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area. To qualify for this designation, the area must meet the following criteria: “is a significant center of illegal drug production, manufacturing, importation, or distribution; state, local, and tribal law enforcement agencies have committed resources to respond to the drug trafficking problem in the area, thereby indicating a determination to respond aggressively to the problem; drug-related activities in the area are having a significant harmful impact in the area and in other areas of the country; and a significant increase in allocation of Federal resources is necessary to respond adequately to drug related activities in the area.”6

Opioid Overdoses

Opioid overdoses are measured by several different organizations. Most use the same datasets to calculate overdose deaths and emergency department (ED) visits but the numbers may vary based on the definitions used by each organization. ED visit data only includes overdoses that do not result in death. Some people who experience a non-fatal overdose may not visit an ED. There is no way to calculate the size of this group.

Emergency Department Visits

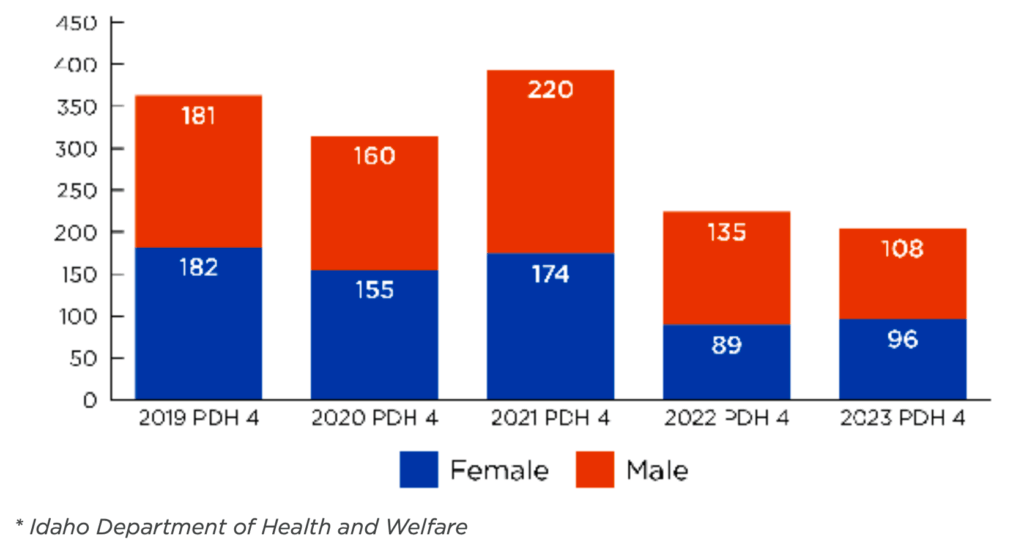

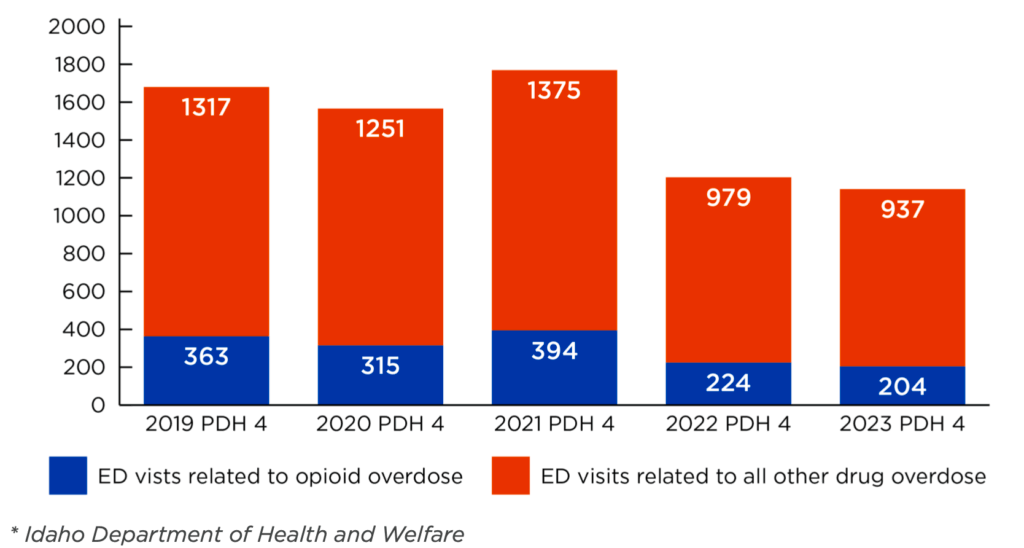

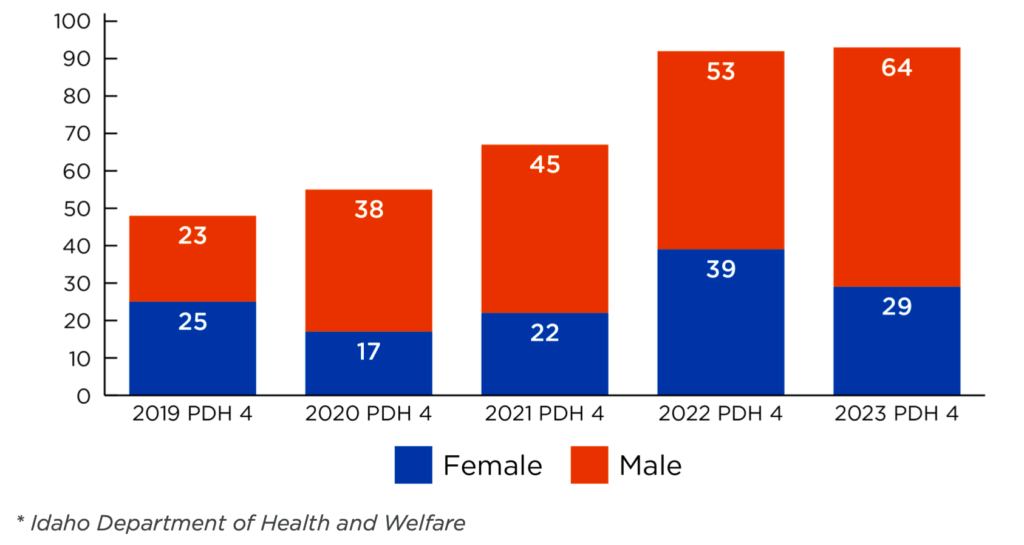

Data from IDHW shows the amount of ED visits related to opioid overdoses in CDH counties has varied over the past five years with notable decreases in 2022 and 2023. Men and women account for about the same number of visits each year. Patients aged 25-44 account for most of these visits.

Figure 3: Opioid Overdose ED Visits by Gender Over Time

ED visits related to opioid overdoses only account for about 20% of all ED visits related to drug overdoses each year. Overall, ED visits from all drug overdoses in CDH counties decreased in 2022 and 2023. This decrease happened statewide but not as dramatically. Most ED opioid overdose visits each year were accidental rather than a result of a suicide attempt (Table 2).

Table 2: Opioid Overdose Type Distribution

| Year | Percent Accidental Overdose | Percent Suicide Overdose |

|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 77% | 23% |

| 2020 | 87% | 13% |

| 2021 | 91% | 9% |

| 2022 | 88% | 12% |

| 2023 | 94% | 6% |

* Idaho Department of Health and Welfare

Figure 4: All Drug Overdose ED Visits by Type Over Time

The following data refers to ED visits from the ESSENCE data related to opioid overdoses. Overdoses specifically noted as caused by fentanyl and heroin are not included in the opioid overdose data. Valley County is missing from the data because there were no opioid overdose patients from Valley County in this timeframe. More details on the methodology for analysis of the ESSENCE data can be found in Appendix A.

Most ED visits related to opioid overdoses in CDH counties are from patients who live in Boise. Since 2019, Boise patients account for 60-70% of all opioid overdose visits. Cities outside of the Boise metro area have had very few patients visit the ED because of opioid overdoses (not including fentanyl or heroin). Most overdoses are considered accidental (Table 4).

Table 3: ED Visits Related to Opioid Overdoses by Patient City

| Year | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Banks | 1 | |||||

| Boise | 72 | 67 | 75 | 92 | 73 | 65 |

| Eagle | 2 | 3 | 1 | 9 | 5 | 3 |

| Garden City | 6 | 8 | 6 | 7 | 3 | 2 |

| Garden Valley | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Glenns Ferry | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Hammett | 7 | 1 | ||||

| Horseshoe Bend | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Kuna | 1 | 7 | 2 | 5 | 7 | |

| Lowman | 1 | |||||

| Meridian | 3 | 13 | 16 | 21 | 20 | 20 |

| Mountain Home | 7 | 5 | 6 | 9 | 3 | 5 |

| Star | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

* ESSENCE Data

Table 4: Percent Opioid Overdose Type by Patient City 2018-2023

| Accidental | Suicide | |

|---|---|---|

| Banks | 100% | 0% |

| Boise | 84% | 16% |

| Eagle | 83% | 17% |

| Garden City | 88% | 13% |

| Garden Valley | 100% | 0% |

| Glenns Ferry | 100% | 0% |

| Hammett | 100% | 0% |

| Horseshoe Bend | 75% | 25% |

| Kuna | 93% | 7% |

| Lowman | 100% | 0% |

| Meridian | 86% | 14% |

| Mountain Home | 91% | 9% |

| Star | 100% | 0% |

* ESSENCE Data

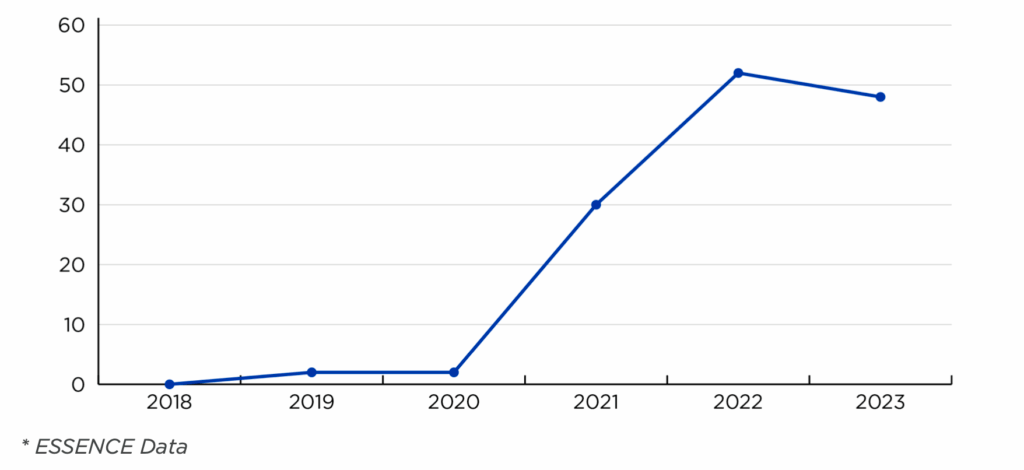

ED visits related to overdoses due to fentanyl usage in CDH increased in 2021, going from just two in 2020 to 30 in 2021. This increase could still be underrepresented as sometimes other opioids may have traces of fentanyl that is unknown to the user so it would not be recorded in the medical notes. All but four fentanyl overdose patients lived in Ada County. Most fentanyl overdose patients (86%) were aged 18-44, over half, 53% were aged 18-30.

Figure 5: Fentanyl Overdose ED Visits Over Time in CDH

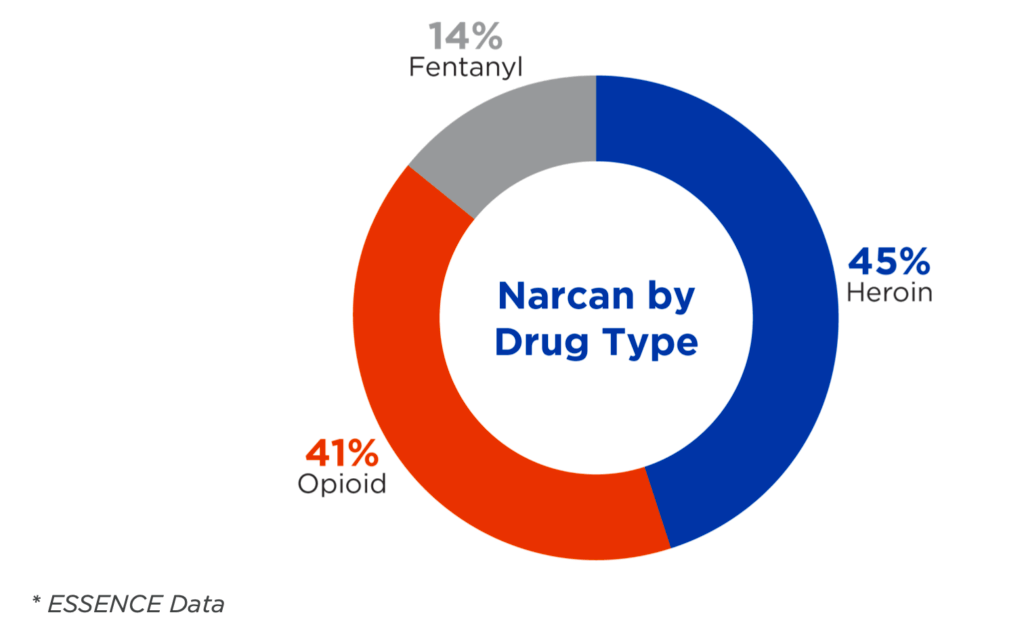

Some overdoses can be treated with naloxone, also known as Narcan, which rapidly reverses the effects of an overdose emergency. Naloxone use in an overdose patient at the emergency department is not officially recorded, but some patient note data includes whether the patient received naloxone as a result of their overdose. Naloxone use was recorded in 175 cases and somewhat more for heroin overdoses than opioid and rarely for fentanyl (Figure 6). Naloxone use was recorded for 37% of heroin overdoses, 19% of fentanyl overdoses, and 11% of other opioid overdoses. A medical code for naloxone administration would make it easier to numerate and understand the level of use.

Figure 6: Naloxone Administration by Drug

A database tracking emergency medical service (EMS) response to overdose events, the Overdose Detection Mapping Application Program (ODMAP), provides a better idea of naloxone administration. Idaho EMS fully adopted ODMAP use in 2022. ODMAP does have gaps in information for measuring opioid overdoses. Data collected in ODMAP only records specific drugs suspected of overdose, the only opioids recorded are oxycodone, fentanyl, and heroin. In some cases, other opioids are noted in the “other category” but without access to a background data of the system, it is difficult to find these cases. There is also a generic “prescription drug” category but this could include opioids and nonopioids. It seems there is not a consistent system or protocol for how to enter suspected drugs involved in the overdose.

Because of the inconsistency of the data, and without a proper understanding of how data entered is recorded, the data regarding opioids is not included in the narrative, but can be found in Appendix B. When looking at all overdoses recorded in ODMAP, a higher percentage of naloxone was administered in overdose cases in 2023 compared to 2022 (Table 5). Also notable, half as many overdoses were recorded in 2023 compared to 2022, this is another indication of inconsistent data recording as all other data implies little or increased change between the years.

Table 5: All Overdoses in ODMAP and Naloxone Administration in CDH Counties

| Year | 2022 | 2023 |

|---|---|---|

| All Overdose Count | 1181 | 526 |

| Percent Naloxone Administration | 18% | 51% |

Naloxone administration does seem to be increasing as naloxone is becoming more accessible and advertised to the public, however there is room for improvement in data collection on naloxone administration on the emergency department level.

Overdose Deaths

Data regarding overdose deaths comes from IDHW and is only reported out at the health district level. Cause and type of death is calculated using death certificate data from the Bureau of Vital Records and Health Statistics.

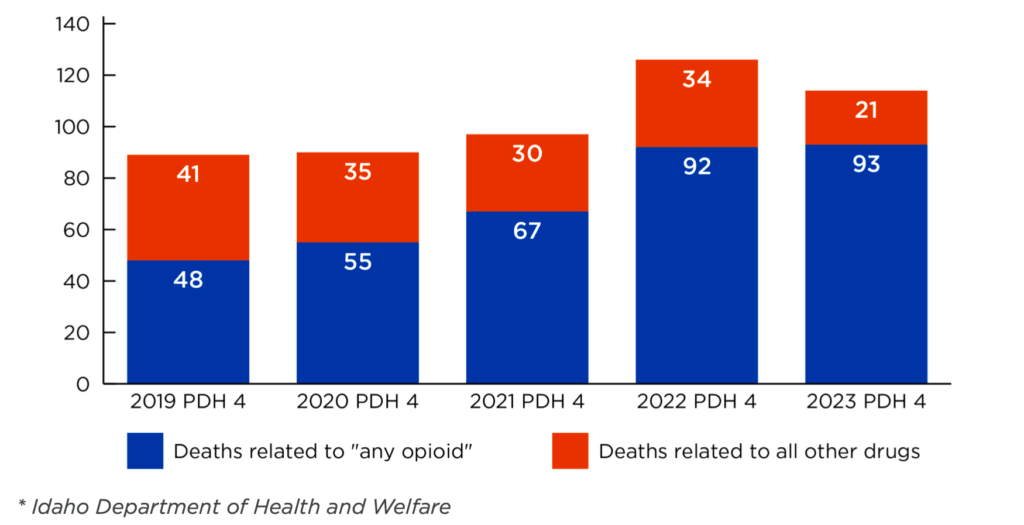

Even though ED visits related to opioid overdose have decreased since 2021, opioid overdose counts in CDH counties have been increasing steadily since 2019. Since ED visit data only includes cases that do not end in death, the increase in death numbers likely means opioid overdoses have not decreased but instead have become more fatal. Each year since 2019, CDH overdose deaths account for about 35% of total overdose deaths in Idaho, meaning that this increase is happening across the state.

The proportion of opioid deaths out of all drug overdose deaths has increased in CDH counties since 2019. In 2019, opioid deaths accounted for 54% of all drug deaths and in 2023, 82% of overdose deaths were related to opioids. This increased proportion is happening statewide but not as dramatically. In 2019, opioid deaths accounted for 51% of overdose deaths across the state and 68% in 2023.

Figure 7: All Drug Overdose Deaths in CDH Over Time by Drug Type

Figure 8: Opioid Overdose Deaths in CDH Over Time by Gender

Men accounted for more than half of all opioid overdose deaths each year except 2019, where females accounted for 52% and males 48% of deaths (Figure 8). There is no pattern across age groups (Table 6) in each year though in 2022 and 2023 ages 25-44 accounted for a little more than half of overdose deaths (54% and 57% respectively). In 2023, over 90% of opioid overdose deaths in CDH counties were accidental, rather than a result of a suicide attempt; this has been increasing since 2019.

Table 6: Opioid Overdose Deaths in CDH Over Time by Age Group

| Year | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11-14 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1%) |

| 15-24 | 6 (13%) | 8 (15%) | 13 (19%) | 13 (14%) | 5 (5%) |

| 25-34 | 9 (19%) | 12 (22%) | 20 (30%) | 28 (30%) | 28 (30%) |

| 35-44 | 9 (19%) | 11 (20%) | 12 (18%) | 22 (24%) | 25 (27%) |

| 45-54 | 8 (17%) | 8 (15%) | 4 (6%) | 11 (12%) | 20 (22%) |

| 55-64 | 9 (19%) | 10 (18%) | 15 (22%) | 13 (14%) | 6 (6%) |

| 65-74 | 5 (11%) | 4 (7%) | 2 (3%) | 5 (6%) | 8 (8%) |

| 75-84 | 1 (2%) | 2 (3%) | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Total | 47 (100%) | 55 (100%) | 67 (100%) | 92 (100%) | 93 (100%) |

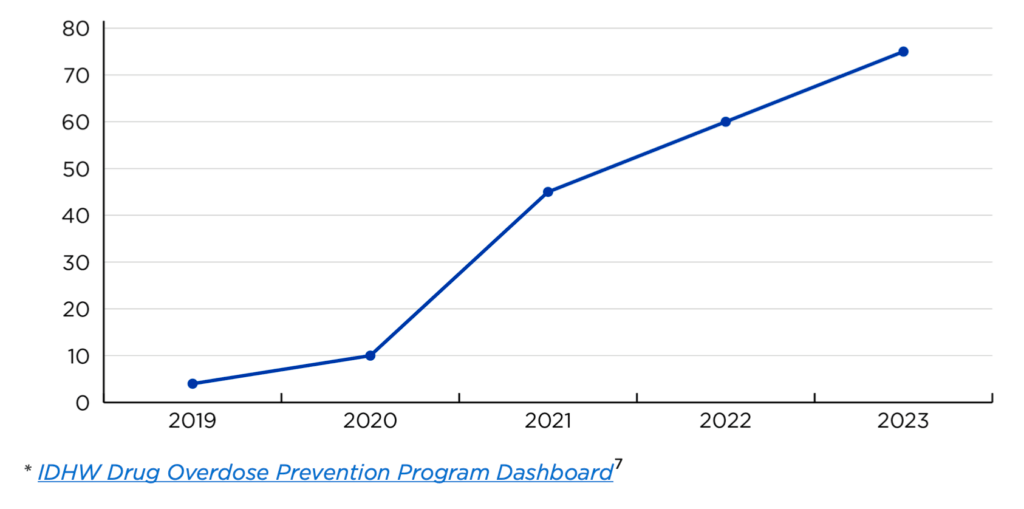

Fentanyl deaths have also been increasing since 2019 (Figure 9). The most dramatic increase was between 2020 to 2021 where deaths increased by 350%. This dramatic increase in fentanyl deaths matches the increase in ED visits. All but four fentanyl deaths since 2019 have been accidental. Men account for most of these deaths each year (Table 7).

Figure 9: Total Fentanyl Deaths Over Time

Table 7: Percent of Fentanyl Deaths by Gender Over Time

| Year | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 0% | 30% | 22% | 35% | 27% |

| Male | 100% | 70% | 78% | 65% | 73% |

* IDHW Drug Overdose Prevention Program Dashboard8

Secondary data provides some insight to the scope of the opioid use and misuse situation in CDH counties. The need for detox services, arrests associated with narcotics, and overdose deaths have increased over the past four years. Most increases started rapidly in 2021. Most overdoses in the CDH area happen to residents living in Ada County. Data collected on opioid use is collected well and consistently by reputable sources, with the exception of ODMAP. Most gaps in data collection are in the level of detail either collected or provided. Providing county level data and creating a way to code naloxone administration are examples of extra details. CDH could meet with the state agencies collecting and sharing this data to determine the best way to receive or collect missing data. The rest of the report details how to provide more services to populations using and misusing opioids.

Return to the beginning of the report

To determine previously funded activities, current community needs, and plans to use funds in the future, team members conducted interviews with local stakeholders and leaders. Six interviews were completed, four with representatives from Ada County, one interview with Valley County, and one interview with Boise County. Representatives from Elmore County were contacted multiple times but an interview could not be scheduled. Table 8 outlines the funds received and spent in Fiscal Years 2022 – 2024, as reported to the Idaho Office of Attorney General; for a breakdown of funds by year, please see Appendix C.

Table 8: Total Funds Received and Spent FY22-FY24

| Location | Received | Spent |

|---|---|---|

| Ada County | $2,633,055.20 | $1,250,000.00 |

| City of Boise | $2,530,136.12 | $238,813.71 |

| City of Eagle | $33,947.81 | $0.00 |

| City of Garden City | $101,914.28 | $101,914.28 |

| City of Kuna | $33,762.11 | $1,500.00 |

| City of Meridian | $438,955.78 | $155,439.29 |

| Boise County | $65,632.80 | $809.27 |

| Elmore County | $176,484.13 | $0.00 |

| City of Mountain Home | $113,168.12 | $14,600.00 |

| Valley County | $148,021.49 | $89,560.00 |

All interviewees indicated that someone, either themselves or another colleague, had to apply for opioid settlement funding from the Idaho Attorney General’s office. Upon receiving funding, recipients spent it on specific activities and prevention efforts. For example, Kuna used funding to hire speakers for youth outreach in local schools to discuss drug use and prevention, while the Meridian Anti-Drug Coalition (MADC) used funds to support a staff position, the Substance Abuse Prevention Coordinator. Valley County, in comparison, distributed funds to local organizations who are working within the community doing either prevention, treatment, or harm reduction10 work. In Boise County, funds were spent in 2024 on supplying first responders with naloxone. While IDHW has previously distributed naloxone statewide, the interviewee noted that there had been several recent overdoses and additional naloxone was purchased to replenish the supply for first responders.

Interviewees from Eagle, Boise Police Department, and Kuna were unsure of how to spend funds moving forward, either due to a fear of misusing money or a lack of knowledge on best practices. Those from Boise and Kuna had either partnered with or were planning to work with individuals or organizations with a deeper understanding of addressing opioid use disorder and with knowledge on how to spend funding moving forward.

While some recipients were unsure of how to determine spending in the future, others have established a process for allocating funding with approval from either outside committees, consortiums, or elected leadership. In particular, Meridian, Valley County, and Boise County have created opportunities for community collaboration.

Valley County specifically offers an example for how to establish a process for distributing funds using a collaborative. Created in 2018 in partnership with CDH, the Valley County Opioid Response Project, or VCORP, is “a collaborative consortium of partners from Valley and Adams Counties and works to increase collaborative relationships between multisector stakeholders, including clinical, and behavioral health”.11 Initially funded through grants from the Health Resources & Service Administration (HRSA), VCORP meets monthly to determine strategies to alleviate the opioid use and overdoses in Valley and Adams counties.12 As part of this work, local service and resource providers can apply for a letter of support from VCORP. Interested parties send a draft letter to the VCORP steering committee outlining their proposal and request for funding; upon review, the steering committee makes a recommendation to the County Commissioners about whether to approve or reject the proposal and the eventual allocation of funds. Through this process, specific and actionable steps are determined, goals are outlined, and evaluation metrics are decided. With a thorough process in place, community partners and resource providers are able to ascertain their impact and place within the larger community context. From interviews with stakeholders and key informants in Valley County, it was apparent that having a thorough process in place allowed for broader community support and useful application of funding.

When interviewees were asked about specific services that would be beneficial which have not yet been offered, many noted increased availability to treatment, education and prevention services, and funding local service providers. Representatives from Meridian, Boise County, and Valley County discussed the need for treatment facilities, particularly for inpatient services. Part of the barrier to accessing this care, interviewees noted, was due to both the cost of treatment and lack of transportation options. For example, individuals in Valley County who need inpatient treatment services must go to Boise City to receive care. As noted in interviews with service providers, organizations will sometimes offer an emergency transportation service for detox or treatment when they are aware of an individual’s need. For example, Ignite Idaho and The ROC, both in McCall, will occasionally drive individuals to Boise City to access treatment. However, this is not a consistently offered option, and transportation barriers persist in rural communities. To better provide access to treatment, interviewees in Valley County are considering foregoing smaller requests in order to potentially support a larger project.

In Meridian, opioid settlement fund recipients are aware of the need for treatment services, but recognize that they do not have the capacity or funds to meet treatment or recovery needs; instead, they are focusing on prevention efforts.

In Boise County, they are hoping to create a treatment program for those who interact with the criminal justice system, like a drug court but for specific situations. The respondent noted it would be beneficial to have specific courts or treatment programs for specific needs, but there aren’t currently enough resources available.

In comparison, interviewees from Kuna and the Boise Police Department noted the importance of prevention and education efforts, especially for youth. While Kuna aims to craft messaging about the impact of drug-use, Boise Police Department is interested in building community and getting parents involved in prevention efforts. In the past, the Boise Police Department has tried to foster community by attending and organizing local events; however, they have not yet held an event about opioid use prevention with settlement funding. They plan to tailor training about drug use and prevention to parents and family members, with the hopes of holding local trainings in the future. In Kuna, the city has partnered with the Ada County Sheriff to create prevention messaging for the local high school. They plan to use settlement funds to potentially buy TVs for the high school to run messaging about the consequences of drug use.

In Eagle, no settlement funding has yet been spent, but the city has taken advantage of the free naloxone distribution program sponsored by IDHW. In the future, they hope to use funds to provide naloxone to different service providers and public-facing organizations, such as the fire department. Additionally, they have previously provided unrelated funding to Allumbaugh House and plan on using settlement funds to support local service providers in the future.

Interviewees were also asked if they had suggestions to other service providers or requests that could beneficially impact their work. Respondents from Kuna, Valley County, and Boise County all indicated that training on Exhibit A and clear guidelines on how funds can be spent would be beneficial – many recipients have received different information on how to interpret and follow Exhibit A, and are concerned about potential audits. In Meridian and Eagle, interviewees noted that community collaboration is helpful in determining unmet needs and opportunities to invest in long-term, high-cost services.

Return to the beginning of the report

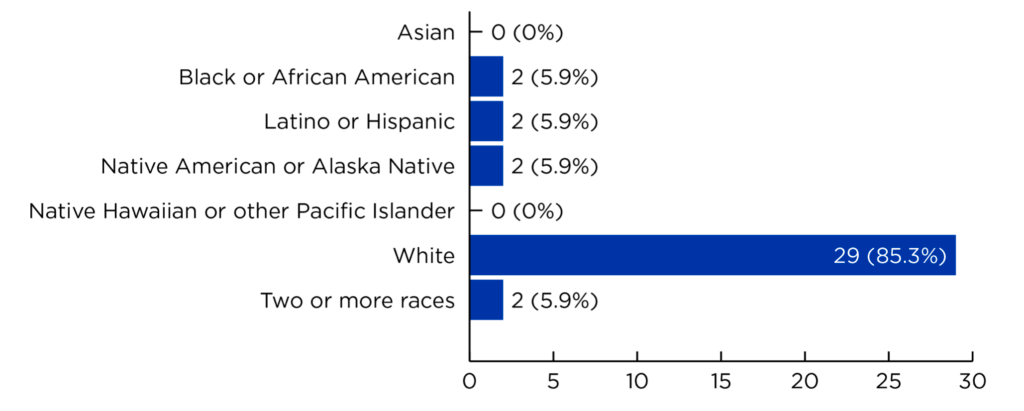

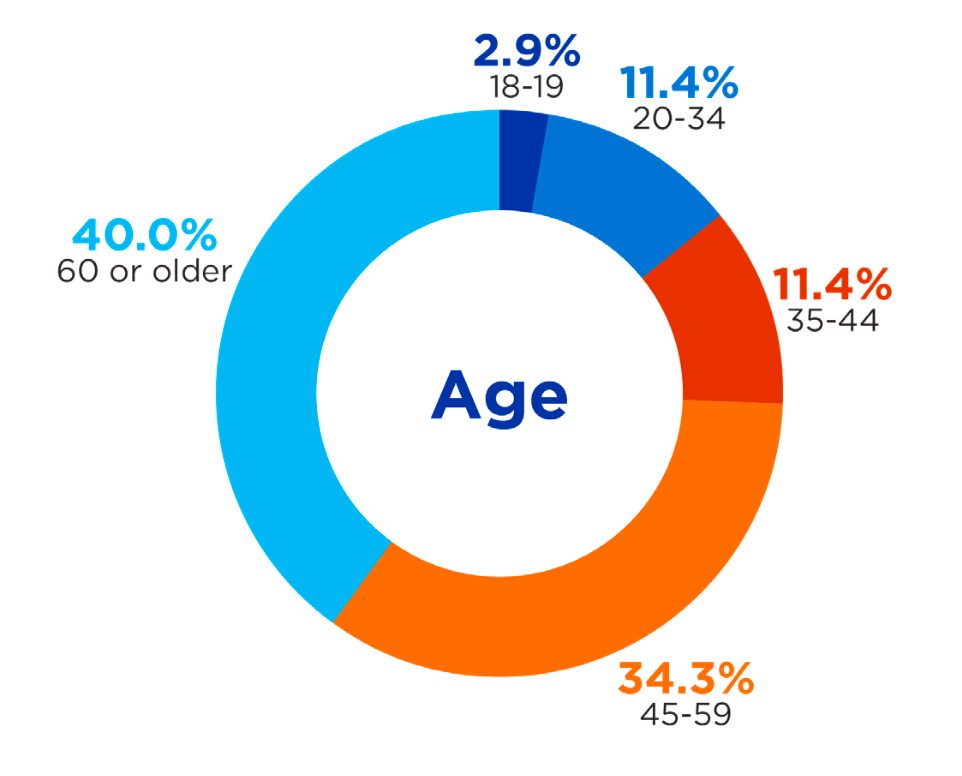

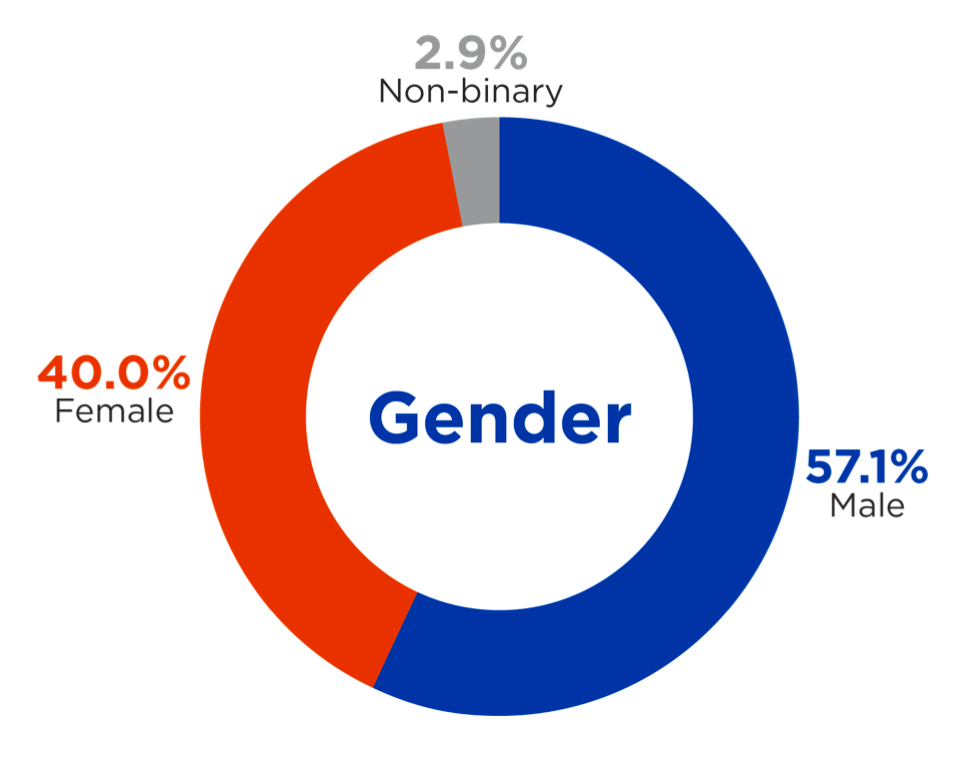

Focus groups attempted to understand the needs of populations using drugs or in recovery. IPI aimed recruitment toward these populations in addition to people who may know or have relationships with them such as family, friends, and service providers. IPI conducted eight focus groups with community members, reaching sixty people including many with personal experience with opioid use. IPI also held four focus groups or interviews with services providers, reaching eight people. Four additional service providers provided responses via survey. Participants were asked, but not required, to provide demographic information. The breakdown of participants by age, gender, and race can be seen in Figures 10, 11, and 12.

Figure 10: Race of Focus Group Participants

Figure 11: Age of Focus Group Participants

Figure 12: Gender of Focus Group Participants

Respondents were also asked about their relationship to opioid use, 41% reported personal use, 56% reported having a friend or relative with history of use, and 18% were service providers.

Current Programs

Participants were asked to share their thoughts on the current services provided for individuals who use drugs, as well as their perspectives on the funding of these services. Many respondents expressed positive views about existing resources and programs, usually reporting they are effective but they need increased capacity and accessibility.

Several individuals emphasized the value of recovery programs in fostering a supportive, understanding community where recovery is celebrated and participants can find peer support from others with lived experience. Informants stressed the importance of ensuring that staff facilitating these programs are well-educated on opioid use, addiction, and the recovery process. Programs with spiritual components and a focus on self-reliance such as Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) and Narcotics Anonymous (NA) were frequently mentioned as positive. While AA and NA meetings are beneficial, participants in smaller counties reported inconsistency in availability because of a lack of funding and regular attendance. AA and NA programs often depend on volunteer help and have limited resources and when meetings are not attended regularly, it can dissuade them from scheduling more or keeping meetings scheduled.

In contrast, many respondents also discussed that some people seeking services will not join groups affiliated with religious organizations and often end up not getting the help they need. They mentioned there is a need for more programs not based in faith or spirituality for people looking for a more neutral path to recovery.

Respondents also emphasized the importance of harm reduction strategies, particularly the wide availability and distribution of naloxone, which were cited as positive outcomes of the opioid settlement funding. Community-wide education around the use of naloxone was identified as a promising way to expand the reach and effectiveness of these lifesaving resources, especially with the support of additional funding.

Ada County, and specifically the City of Boise, was recognized as having the most comprehensive range of outpatient services, mental health programs, sober living facilities, and drug-use support services among all counties served by CDH.

Some counties have started programs that could improve accessibility but need more financial support. For example, Elmore County highlighted the need for increased funding for the Community Health EMS (CHEMS) program, noting that additional resources would help expand staffing, outreach efforts, and the overall number of people served.

Needed Programs

Participants were asked to identify any programs they would like to see offered that are not yet available. Major themes that emerged from the data analysis centered on housing, the need to scale up existing services, access to treatment, and the importance of centralized knowledge about resources.

Respondents generally felt that current services are of good quality but are not sufficient to meet the needs of all counties and populations served by CDH. One frequently mentioned theme from rural areas was the need to expand existing services to decrease travel time and transportation need to receive care and access resources. All respondents expressed a need to expand services that are affordable and open to individuals without Medicaid or private health insurance.

Unhoused key informants highlighted the importance of expanding harm reduction services—such as needle exchange programs and access to naloxone—to also include education on how to administer these medications. Participants did not specify which type of naloxone administration they needed education on. There was a general sentiment of wanting to gain as much information as they could on ways to take care of each other in their communities which included naloxone administration and first aid training. They emphasized that this education should prioritize visual learning (illustrations) over text, to improve comprehension and accessibility.

Housing emerged as another major theme across all counties in multiple focus groups and interviews. Respondents stressed the urgent need for affordable housing options not only for service users but also for service providers, particularly in rural communities like McCall. Service providers in Valley County noted that the lack of affordable housing has become a key barrier to recruiting and retaining necessary staff. In addition to limited affordable housing, there is a notable shortage of transitional housing and sober living facilities.

Another critical theme was the need for accessible, centralized information about available resources. While the internet is a valuable tool, many respondents expressed that only those with a high level of digital literacy are able to easily locate and navigate these resources. Participants recommended the creation of a centralized, user-friendly directory of services, particularly for individuals reentering society after incarceration or experiencing homelessness. Although such directories do exist, they are mostly in electronic formats. Printed versions of directories in gathering places like shelters would be more accessible to individuals with limited digital skills.

Across the board, a common theme emerged: a strong desire for funding to be used in ways that expand access to services like detox centers, transitional housing, and accessible education, particularly in rural areas within the CDH region.

Return to the beginning of the report

An assessment of existing services was conducted using an existing CDH catalog of available services in each county and was updated by performing web-based research through search engines to gather information. The new catalog of services was submitted alongside this report. The updated information was examined alongside data gathered from focus group sessions and resulted in the identification of strengths, gaps, needs, and barriers in each county of Region IV. Qualitative data gathered from focus groups supports the findings of the assessment and provides additional commentary on the specifics of each community. Some items mentioned have been previously discussed in the report.

Most strengths can be categorized as availability, accessibility, and diversity of services in a given area with wide variations between counties. Ada County leads in its strengths, with the greatest quantity and diversity of available services and resources for its residents. Ada County is home to an abundance of outpatient medical and behavioral health providers, several inpatient options, pharmacies, and other supports, such as thrift stores, community programs, food support, after-school programs, employment and housing support, as well as emergency services and shelters. Focus group data echoed similar strengths, including access to mental health care and primary care, access to naloxone, availability of recovery programs, and availability of STI testing.

While these services may exist in a smaller capacity in other counties, each county boasts its own strength tailored to the needs of their community. Elmore County is home to several behavioral health providers, community-based support, and food assistance. Focus group participants shared that Elmore County was also strong in providing education around skill-building and infection prevention, availability of mental health and outpatient services, and recovery programs. Valley County finds its primary strength in collaboration, as was discussed at length during focus groups, amplifying the work done by local providers, behavioral health services, and community-based supports. Focus group data identified strengths in prevention education, naloxone access, access to primary care providers, and recovery programs. Boise County identified strengths in accessibility to naloxone and availability of prevention education in addition to a wide service area for behavioral health needs and focus group data echoes these strengths.

Counties also differ in where gaps in service coverage exist in the community. Ada County, serving a large population, identified several gaps in services, primarily in affordable housing, day shelters and medical support in shelters, overdose prevention education, health literacy, and addressing the social stigma that exists for the populations that utilize these services. Focus group data revealed the need for additional funding to be used for affordable housing options, shelter support, relapse prevention, needle exchange, phone services, programs without law enforcement or religion, GED and further education support for patients, support for families, grief and loss groups, and celebrations for sobriety and recovery achievements. Participants also shared the need for provider education, primarily around comprehensive knowledge of available resources and the need for providers with lived experience.

Elmore County has a clear gap in available support services such as employment, housing, and inpatient services. Focus groups in Elmore County also identified a common barrier to receiving support as traveling to Ada County to access more diverse forms of support. Focus group data found that additional funding was necessary to scale the capacity of current services, create affordable housing, create treatment and transitional facilities, provide harm reduction services and needle exchanges, as well as peer and family support.

Valley County recognized a similar challenge for that community, noting that although they did have a variety of services, many services required travel to Ada County to be accessed. Valley County also identified gaps in affordable housing and support, peer support, detox housing and sober living residencies, in addition to a lack of third spaces. Focus group data found that additional funding is necessary to create a crisis program, to create sober living or transitional housing, to build community between services, and provide peer support.

Boise County has a gap in services available after school for youth in the area, as was discussed during focus groups but is also evident in the assessment. Focus group data revealed the need for additional funding to support youth in the county through community engagement, transportation for youth, after school programs and activities, in addition to vape detectors.

Though Ada County does have the largest quantity of available services in Region IV, it was mentioned that there are still not enough resources to effectively meet demand. Other barriers include the complexity of navigating services without guidance, lack of knowledge around available services, and insurance requirements to access services, transportation challenges, and the fear of seeking services amid negative social stigma.

The primary barriers for patients in Elmore, Valley, and Boise counties is traveling to larger counties to access services and the general lack of available services in their community. In Elmore County, other barriers include the cost of peer support training, the service capacity of agencies, and accessing services that do not include religious elements. In Valley County and Boise County, the service capacity of local agencies was also identified as a barrier.

Based on data gathered during focus groups, Ada County could benefit from prioritizing education around safe medication use, naloxone accessibility and use, substance testing strips, harm reduction, and CPR training for the general public, especially those in vulnerable populations. Ada County could also focus on housing, veteran healthcare support, and mobile crisis and health services.

Elmore County could benefit from prioritizing the creation of peer support opportunities and continue funding community centers that already provide services to the community. Elmore County could also focus on transitional and affordable housing, detox support, and other community supports such as health fairs, employment, and transportation.

Valley and Boise Counties could both prioritize prevention education that is available and appropriate for all ages.

Table 9: County Strengths, Gaps, Needs, Barriers

| Strengths | Gaps | Needs | Barriers | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ada County | – Mental Health – Naloxone Access – Primary Care – Recovery Programs – STI Testing |

– Affordable Housing – Correctional System – Cost of Medications – Day Shelter – Education – Health Literacy – Outpatient Services – Prevention – Education – Services Without Religion – Shelter/Mobile – Medical/Dental Services – Social Stigma |

– Achievement – Celebrations – Education Pathways – Family Support – Grief/Loss Support – Housing – Needle Exchange – Phone Services – Programs without Law Enforcement – Provider Education – Relapse Prevention – Shelter Funding – Social Stigma |

– Fear – Insurance – Service – Advertisement – Service Capacity – Service Consistency – Service Directory – Service Navigation – Services without Religion – Transportation |

| Elmore County | – Education – Housing – Mental Health – Outpatient Services – Recovery Programs |

– Affordable Housing – Crisis Services – Harm Reduction – Services without Religion – Sober Living Transportation – Veteran Services – Youth Services |

– Affordable Housing – Family Support – Medication – Management – Methadone Clinic – Needle Exchange – Peer Support – Provider Education – Resource Officer – Service Scaling – Transitional Facility – Transportation Services – Treatment Facilities |

– Education – Accessibility – Peer Support – Training Cost – Service Capacity – Service Cost – Services without Religion – Traveling for Care |

| Valley County | – Prevention – Education – Naloxone Access – Primary Care – Recovery Programs |

– Affordable Housing – Detox Housing – Outpatient Services – Peer Support – Short/Long Term Housing – Sober Living – Social Stigma – Third Spaces – Traveling for Care |

– Crisis Program – Detox/Transitional Facility – Patient Hotline – Peer Support – Prevention in Jails – Service – Collaboration – Sober Living |

– Service Availability – Service Capacity – Traveling for Care |

| Boise County | – Naloxone Access – Prevention – Education |

– Youth Activities | – After School Programs – Vape Detectors – Youth Engagement – Youth Transportation |

– Service Capacity – Traveling for Care |

Table 10: County Goals and Priorities

| Goals or Priorities | |

|---|---|

| Ada County | – Education (medication, naloxone, testing, CPR) – Harm Reduction (prevention education, naloxone, narcan, needle exchange) – Housing – Mobile Crisis – Mobile Medical and Dental Care – Sharps Box – Veteran Healthcare |

| Elmore County | – Community Center Support – Detox Facility – Employment Support – Health Fairs – Housing Support – Peer Support Training – Transitional Housing – Transportation Services |

| Valley County | Prevention Education |

| Boise County | Prevention Education |

* Priorities are those described by participants in the stakeholder and key informant interviews

Return to the beginning of the report

Drawing from stakeholder and key informant input, secondary data analysis, and community capacity assessments, the following recommendations outline potential activities and investments that address the most pressing regional needs related to opioid use, misuse, and overdose. These recommendations are aligned with either the approved opioid settlement abatement strategies (i.e., Exhibit A) or Central District Health’s core values (Excellence, Positive Impact, Partnership, Innovation, Credibility and Humanity).

1. Strengthen Coordination and Strategic Allocation of Funds

- Establish a regional steering committee to provide guidance on funding priorities, evaluate proposals, and ensure alignment with community needs and approved abatement strategies. This committee can also support smaller municipalities and organizations that may lack capacity or clarity on fund utilization. Steering committee members could include representatives from the justice system, local jurisdictions, school districts, service providers (e.g, health care, EMS, etc.), and people with lived experience.

- Encourage collaborative planning and resource sharing across counties and cities to avoid duplication of efforts and scale what is working region-wide.

2. Invest In and Expand Proven Services

- Prioritize funding for programs that demonstrate effectiveness, such as harm reduction efforts, peer support networks, and prevention coalitions, to scale services across underserved communities.

- Examine opportunities to invest in housing-related services.

- Enhance transportation services to address one of the most commonly cited barriers to treatment and support—particularly in rural counties.

3. Implement Innovative Recovery Support Models

- Support the creation of additional recovery groups, including non-faith based or law enforcement models, to ensure low barrier access to support services. – Increase opportunities for peer-support models.

- Fund the establishment or expansion of detox centers, especially in areas where individuals currently must travel long distances to access care.

4. Improve Access to Resources and Education

- Provide service provider trainings to ensure the most up to date knowledge is available and understood including in available funds and allowable expenses.

- Develop and disseminate user-friendly, multilingual directories of local services, available in both print and digital formats, to reach individuals with limited digital access or literacy.

- Invest in evidence-based, age-appropriate prevention and education programs (e.g. harm reduction interventions), particularly in partnership with school districts, after-school programs, and youth-serving organizations.

- Collaborate with individuals with lived experience to inform educational resources and engage in educational programming.

5. Promote Continuity of Care Across Systems

- Develop coordinated entry systems that link individuals exiting treatment, incarceration, or homelessness to housing and recovery resources, including Permanent Supportive Housing (PSH).

- Build off of the regional steering committee to develop located collaboratives, using VCORP as a model.

- Foster partnerships with correctional systems to provide pre-release planning and post-release support services, ensuring continuity of care for justice-involved individuals.

6. Leverage and Expand Community-Based Partnerships

- Create opportunities for multi-sector partnerships that include healthcare providers, behavioral health organizations, schools, peer recovery specialists, and public safety entities.

- Encourage local innovation through mini-grants or community challenge funds that empower grassroots solutions aligned with regional priorities.

Return to the beginning of the report

The findings from this environmental scan underscore both the complexity of the opioid crisis within the CDH region and the pressing need for coordinated, community driven solutions. While each county and city within the region brings unique strengths, challenges, and priorities to the table, a unifying theme emerged: there is strong local commitment to addressing opioid use, misuse, and overdose—but significant barriers remain in translating that commitment into accessible and sustainable action.

Stakeholders and key informants consistently highlighted gaps in affordable housing, access to treatment and recovery services, transportation, and community-based education and prevention programming. These challenges are particularly acute in rural areas, where infrastructure and staffing shortages further limit service delivery. At the same time, promising models like Valley County’s VCORP initiative offer valuable insights into how collaborative planning, transparent decision-making, and targeted investments can amplify impact and promote equitable access to care.

This report presents a set of recommendations and key investment areas that align with both the approved uses of opioid settlement funds and CDH’s values of positive impact, partnership, innovation, and humanity. By investing in what is already working, expanding proven services to underserved areas, supporting new strategies such as non-faith-based recovery groups and user-friendly resource directories, and enhancing coordination across jurisdictions, CDH and its partners are well-positioned to build a regional response that is strategic, inclusive, and evidence-informed.

The five-year action plan informed through this project should offer a flexible, living framework to guide implementation, support local leaders, and ensure that opioid settlement resources are deployed in ways that are not only effective, but transformative for the communities they serve.

Return to the beginning of the report

IPI received ESSENCE data from CDH in March 2025. The data includes all ED cases reporting poisonings from 2018 to 2023. The data only includes non-fatal overdose data. Data included various demographic details about the patient as well as medical details associated with the visit. The data did not include any information that would make the client identifiable.

To enumerate opioid, fentanyl, and heroin deaths, IPI used the chief complaint and discharge diagnosis (CCDD) and ICD-10 codes. Data included in analysis includes all patients with the following codes:

CCDD

CDC Opioid Overdose v1-4

ICD-10

T40.601A

T40.2X1A

T40.1X1A

T40.411A

T40.604A

T40.2X2A

T40.2X4A

T50.901A

The final dataset included 1,043 ED cases. These cases were determined as fentanyl, heroin, and all other opioid overdoses using the CCDD codes. Fentanyl and heroin overdoses are assigned the general CDC Opioid Overdose v1-4 codes in addition to the codes specific to heroin and fentanyl (CDC Heroin Overdose v1-4 and CDC Fentanyl Overdose v1-4). The remaining cases were considered “other opioid overdoses.” All suicide cases were also labeled as such using the CCDD codes ”CDC Suicide Attempt v1-4” and CDC Suicidal Ideation v1-4.”

The data included data markers for the location of the ED and for the patient city of residents (e.g. it allows to see a Boise County resident visiting an Ada County ED). After completing the cleaning, there were not any cases from Valley County EDs or any Valley County residents. The original dataset does only include data from one of the two ED locations in Valley county. It would be interesting to know the number of overdose patients visiting the omitted ED.

Return to the beginning of the report

The level of access available to IPI in ODMAP made it so the team could see the map and the individual cases on the map. The team could also use filters to see different groupings of the cases on the map, but the data was not available for export. This made it difficult to perform a proper analysis. There were a few other barriers to performing analysis. One, it is not clear how opioids are classified in ODMAP. Two, it is also unclear if ODMAP is used the same way by EMS departments across the state making comparisons and ranking difficult.

The data available on fentanyl and oxycodone overdoses is found below. The fentanyl data is comparable to overdose deaths and ED visits, the oxycodone data does not have any data for comparison.

Table 11: Oxycodone Overdoses in ODMAP

| Oxycodone | 2022 | 2023 |

|---|---|---|

| District 4* | ||

| Total Suspected Overdoses | 3 | 13 |

| Suspected Fatal Overdoses | 2 | 3 |

| Naloxone | 1 | 9 |

| Multiple Naloxone | 1 | 7 |

| Single Naloxone | 0 | 2 |

* Only Ada County had reported oxycodone overdose cases.

Table 12: Fentanyl Overdoses in ODMAP

| Fentanyl | 2022 | 2023 |

|---|---|---|

| District 4* | ||

| Total Suspected Overdoses | 30 | 56 |

| Suspected Fatal Overdoses | 13 | 11 |

| Naloxone | 17 | 17 |

| Multiple Naloxone | 14 | 12 |

| Single Naloxone | 3 | 5 |

* Ada County had all but three reported fentanyl overdose cases. The other three were in Elmore County in 2023 and were non-fatal and did not involve naloxone.

Return to the beginning of the report

Table 13: Total Funds Received and Spent FY2024 (July 1, 2023 – June 30, 2024)

| Location | Received | Spent |

|---|---|---|

| Ada County | $1,381,239.84 | $1,250,000.00 |

| City of Boise | $1,327,250.87 | $238,813.71 |

| City of Eagle | $17,808.24 | $0.00 |

| City of Garden City | $49,279.78 | $49,279.78 |

| City of Kuna | $16,325.37 | $0.00 |

| City of Meridian | $212,253.27 | $69,384.10 |

| Boise County | $34,429.44 | $809.27 |

| Elmore County | $92,579.49 | $0.00 |

| City of Mountain Home | $59,365.37 | $14,600.00 |

| Valley County | $83,999.28 | $24,560.00 |

* Office of the Attorney General, State of Idaho13

Table 14: Total Funds Received and Spent FY2023 (July 1, 2022 – June 30, 2023)

| Location | Received | Spent |

|---|---|---|

| Ada County | $1,251,815.36 | $0.00 |

| City of Boise | $1,011,598.23 | $0.00 |

| City of Eagle | $13,573.00 | $0.00 |

| City of Garden City | $44,264.38 | $52,634.50 |

| City of Kuna | $17,436.74 | $1,500.00 |

| City of Meridian | $190,651.48 | $86,055.19 |

| Boise County | $31,203.36 | $0.00 |

| Elmore County | $83,904.64 | $0.00 |

| City of Mountain Home | $45,246.85 | $0.00 |

| Valley County | $64,022.21 | $65,000.00 |

* Office of the Attorney General, State of Idaho14

Table 15: Total Funds Received and Spent FY2022 (July 1, 2021 – June 30, 2022)

| Location | Received | Spent |

|---|---|---|

| Ada County | – | – |

| City of Boise | $191,287.02 | $0.00 |

| City of Eagle | $2,566.57 | $0.00 |

| City of Garden City | $8,370.12 | $0.00 |

| City of Kuna | – | – |

| City of Meridian | $36,051.03 | $0.00 |

| Boise County | – | – |

| Elmore County | – | – |

| City of Mountain Home | $8,555.90 | $0.00 |

| Valley County | – | – |

* Office of the Attorney General, State of Idaho15

Return to the beginning of the report

Endnotes

1 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024, November 7). Opioid dispensing rate maps. https:// www.cdc.gov/overdose-prevention/data-research/facts-stats/opioid-dispensing-rate-maps.html

2 Ibid.

3 Terry Reilly. (n.d.). Allumbaugh House. https://www.trhs.org/allumbaugh-house: Allumbaugh House only accepts insured patients who have no mental health/substance disorder coverage available to them.

4 Idaho State Police. (2024). Crime in Idaho data dashboard. https://isp.idaho.gov/pgr/cii-dashboard/

5 Idaho State Police, State Police Uniform Crime Reporting. (n.d.). Drug seized report. https://nibrs.isp.idaho. gov/CrimeInIdaho/Report/NIBRSDrugSeizedReport

6 United States Drug Enforcement Administration. (n.d.). High intensity drug trafficking areas. https://www. dea.gov/operations/hidta

7 Idaho Department of Health and Welfare. (2024). Drug overdose prevention program. https://www. gethealthy.dhw.idaho.gov/drug-overdose-dashboard

8 Ibid.

9 Office of the Attorney General, State of Idaho. (2025). Opioid Settlement – Financial Reports. https://www. ag.idaho.gov/consumer-protection/opioid-settlement/opioid-settlement-financial-reports/

10 Throughout the report, harm reduction is mentioned, many participants cited a need for harm reduction but did not provide specific details on what they meant unless otherwise listed.

11 Central District Health. (2024, June 11). Valley County Opioid Response Project. https://cdh.idaho.gov/ community-health/community-health-partnerships/valley-county-opioid-response-project/

12 Ibid.

13 See note 9 above. Office of the Attorney General, State of Idaho (2025).

14 See note 9 above. Office of the Attorney General, State of Idaho (2025).

15 See note 9 above. Office of the Attorney General, State of Idaho (2025).