Changing Influences on Boise’s Growth Pattern as Exhibited through Maps, 1863-1930.

Johnny Hester

Boise State University

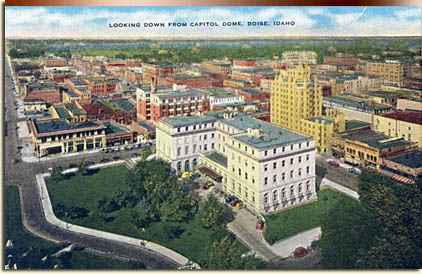

Understanding Boise through Maps Unlike many other towns, however, Boise continued to develop once the mines disappeared. We see evidence of many of Boise’s early leading growth influences in contemporary maps. Whether in the form of remote subdivisions, satellite communities, or changing settlement patterns of the city, each answers, in part, questions about how and why the city developed in the manner in which it did. Specifically, how did Boise survive and flourish with the odds seemingly against a city of any consequence arising out of a desert valley located in one of the more remote locations along the Oregon Trail?

Maps are of particular use in answering questions concerning city growth given that they represent the physical attributes of an urban area, complementing any statistical data available such as population numbers. While the use of ordinary street maps allows for a great overall view of a city’s layout, plat and Sanborn fire insurance maps provide detail not often available in other illustrations. Plats are important for exhibiting the boundaries and subdivisions of a specific piece of land. Among other things, they are useful for examining historical land-use patterns. Originally intended to aid in establishing fire insurance liability, Sanborn maps today are extremely useful in researching urban development because of their detail, accuracy, and standardization over several decades. This makes them valuable sources for analyzing the evolution of specific locations and exploring growth patterns.

One might question the role of location, often thought by many to be primary in influencing city development, in the early success of Boise. The arid, high desert of the Boise Valley was not an obvious setting for a city. Thousands of emigrants passed through the heart of the future city site on their way west failing to recognize any urban potential. Certainly, the thousands of Oregon Trail travelers were much more indifferent to the landscape than the ones in the legend of the 1833 Bonneville party who cried out upon seeing the valley for the first time, “les bois, voyez les bois” or “the woods, see the woods.”1 Any voyagers subsequent to the Bonneville party and possessing half the enthusiasm should have seen the potential but instead crossed the valley uninterested.

Some individuals make the argument that location is the undisputed principal factor in the success of almost any given city. Many real estate investors of the nineteenth century adopted the view of New York, land speculator Charles Butler concerning the importance of location. On the future of the emergent Chicago, Butler insisted that its setting guaranteed “greatness.”2 City boosters pointed to “natural” advantages of the location when discussing a certain city’s imminent success. These advantages included healthy climate, fertile soils, accessible transportation routes, and other factors advantageous to a locale that “nature had designated for urban greatness.”3 For many, then and now, cities like Chicago and St. Louis were destined for success due to their central locations and proximity to navigable waterways. Their attainment as major commercial metropolitan areas does not surprise many of us today. How could cities with such “natural advantages” not flourish when all man had to do was “gather up the gifts so profusely showered upon him.”4 In such a setting, according to William Cronon, boosters believed nature would almost build the city itself.

Contrary to this belief, the location of a city actually plays only a small role in its success. While location can have its advantages, it does not guarantee urban growth and development. Jane Jacobs correctly stated that one of the most common resources in the world is good locations for commercial centers and that most do not become cities.5 Investors of the nineteenth century erected numerous towns on the Great Lakes in sites similar to that of Chicago and few developed into cities of any noticeable significance.6 Lawrence H. Larsen wrote that successful urban areas originated from the promotion and building of sites, no matter how undesirable, by skilled entrepreneurs.7 Jacobs agreed by stating that the existence of cities and the source of their development “lie within themselves” and are not attributable to location or given resources.8 She pointed to Sag Harbor on Long Island and Portsmouth, North Carolina, as examples of “natural” city settings in which a major city failed to develop. Writer John Reader also rejects the role of location as an explanation of why some cities prosper and instead credits economics, politics, and religion as the primary factors while acknowledging that modern cities are much more complicated.9 All of this might help explain the success of cities such as the desert situated Las Vegas or the now densely inhabited Los Angeles, located too far inland according to one US senator in the 1920s.10 Cities grow primarily for economic reasons, sometimes benefiting from their location and very often in spite of it.

Mining Town

While location may not be the major factor in a city’s eventual success, something does influence the initial choice of locations in which to build; the nearby fort did that for Boise. In 1863, Major Pinkney Lugenbeel of the Union Army founded Fort Boise next to the foothills below the Boise Basin. The fort served dual purposes. The soldiers were there to protect firstly the miners from local Indians who were no doubt feeling threatened by the sudden non-Indian population explosion. Military records agree the reason for the establishment of a fort in the Boise Valley was “to construct Fort Boise, Idaho, and to protect the miners.”11 To a lesser extent, but along the same line, the army also served to protect the Indians from miners who might start a war thus disrupting western migration and local mining. The second reason for Fort Boise’s construction was so that the Union could protect the enormous amounts of gold and silver coming from the Boise Basin and Owyhee Mountains.12 The fear of Confederate sympathizers working among the mining communities compelled the US Government to monitor all of the wealth coming out of the recently established territory.13 According to book editor Annie Laurie Bird, many historians and writers of the time maintained that the establishment of Idaho Territory was a direct result of this gold and silver rush. By making Idaho, an official territory, the government had a stronger claim to everything within its boundaries.

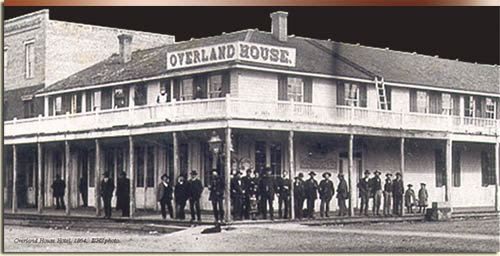

The day after construction of the new fort began, several men met at the Davis-Ritchey cabin to organize the town site company.14 Twenty names appear on the plat including settlers as well as soldiers of the nearby fort.15 There was no certainty that the new town of Boise City would amount to anything though it seemed an opportunity if not a necessity to some. While many felt certain that the town would succeed as a supply center for the nearby mines, others were more skeptical. In a letter dated July 27, 1863 Lugenbeel wrote of his share of land, “If the town ever becomes worth anything, I will give the lots to you children…there will be a town somewhere in this valley which will be of good size, but where it will be, remains to be determined.”16 The town continued to grow despite the skepticism of a few of its early residents. Among the new arrivals were several business-minded men who settled in and around Boise City in the following months. These men sought to get in on the ground floor of the burgeoning city and helped to inspire its growth. By September of 1864, about sixteen hundred people lived within the city limits.17

It was typical in the nineteenth century for mining towns and mining supply towns to expand quickly within the first months and sometimes years of the first mineral strike. While many mining towns “sprang up” almost instantly, settlers planned or surveyed and organized others, such as Boise.18 Difficulty came when resources ran dry forcing towns to find other means to stimulate growth or, at the very least, maintain a substantial portion of the population already attained. Many towns during the nineteenth century failed when their single-source economic foundation vanished.19 Most mining towns were short lived as evidenced by the abandoned remnants littering the West of once populous centers of economic, residential, and recreational activity. Due to stiff competition, cities often could not afford to rest on their laurels. Each new gold or silver strike meant the demise of many previous boomtowns. In the Rocky Mountain ranges beginning in 1849, each successive strike sapped established towns as residents left for the new camp.20

Virginia City, Nevada, developed quickly as a mining town of around twenty-five thousand by 1876 only to lose sixty percent of the population as workers exhausted the mines over the next four years.21 Reasons for the failure to keep citizens vary by city though they were usually economic based. For Virginia City, the inability to develop an agricultural foundation in the nearby mountains contributed to the decline.22 Leadville, Colorado, suffered the same fate while Denver prospered thanks to its diversity as both a mining-supply hub and railroad town.

Boise too diversified its economic base in the early years and failed to take on the shape of typical mining towns that were often located in small, rugged spaces in canyons or on hillsides.23 Instead, Boise looked much more like the well-surveyed company towns sometimes built by mining or lumber corporations. While Boise served some of the same purposes as a company town, it was not. Company towns tended to have uniform structures built and owned by one corporation. Early Boise was primarily a collection of private businesspersons and private business organizations hoping to profit by catering to the needs of the local miners.

Therefore, mining influenced not only the site of the city of Boise but also contributed to its early growth as a supply center for the mining towns. While Boise grew steadily in the first few years, citizens realized the necessity of alternate city identities in order to strengthen the foundation of their individual economic ventures and the town. Mining was not stable enough to support commercial centers long-term. By 1870, several local mining towns had declined significantly. Between 1864 and 1870, Idaho City dropped from seven thousand to 889, Pioneerville from two thousand to 477, and Placerville from twenty five hundred to 318.24 Important to Boise’s stability during this time was the vote to move the territorial capital from Lewiston to Boise in 1864. With a strong beginning as a commercial based city and now territorial capital, Boise residents next sought other avenues in order to strengthen the their new city. One such opportunity came in the form of irrigation.

Agricultural Town

Large-scale irrigation affects the city shape in a couple of notable ways. Firstly, a successful irrigation system usually promotes substantial population growth. Potentially productive land attracted settlers in great numbers in the late nineteenth-century American West. Secondly, dams, canals, and reservoirs influenced settlement patterns in both the urban and rural areas. Close proximity to a water source allows for quicker and easier access to irrigation, therefore, communities sometimes grow toward the resource. Likewise, Boise has always had a close relationship with the nearby river as it provides much of the city’s water supply and has influenced city growth as a geographical boundary, flood threat, and, later, important development location. Initially the river kept the city of Boise isolated primarily to the north. When the city did grow to the south side, fear of flooding kept development near the banks at a minimum. For a number of years the river and its sparsely populated shores cut a wide swath through the city. Irrigation and related construction projects, helped to change that.

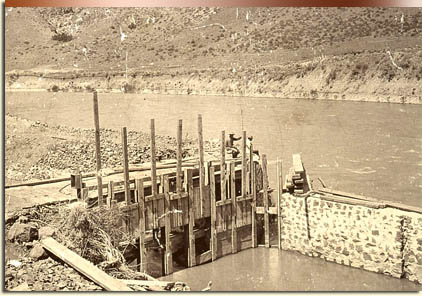

The effect of irrigation on the city of Boise is unmistakable as intricate canal systems, along with diversion dams, enabled locals to transport water from the Boise River to farms on the Boise Bench and other remote areas. Before significant irrigation in the valley, farmers had to locate their farmstead within close proximity to a substantial water source, usually the Boise River. Tom Davis, for example, settled alongside the river in current day Julia Davis Park where he dug a ditch from the river to his orchard.25 In fact, farmers utilized much of the land along the Boise River in the early years of Boise history as few deemed it worthy of little else due to flooding. As county population grew, however, citizens realized the need for irrigable land beyond the riverbanks. Many looked to the large expanse of land south of Boise just below the Boise Bench as well as downstream to the west.

Several small canal companies contributed to moderate early success of agriculture in the Boise Valley. From 1863 to 1870, land under cultivation grew from virtually zero to 19,180 acres and by 1880, there were 256 farms totaling 80,853 acres.26 Incorporated towns within the valley included 2,675 people in 1870 and 4,674 in 1880 with an estimated equal number living outside city limits on farms.27 Geographical boundaries and relatively unsophisticated irrigation methods limited this growth to a particular locale. By the 1880’s, farms and towns inhabited much of the land below the Bench as agricultural development in the Boise Valley had reached its limits. For some time, people of the valley realized that serious agricultural development awaited them above the Bench.

In 1865, Alexander Rossi built a canal to irrigate the ‘bench’ on the south side of the river and later sold his water right to William B. Morris.28 William Ridenbaugh, Morris’ nephew, inherited it in 1878 and applied his own name to the canal upon completion.29 The Ridenbaugh canal system continued to grow through several ownership changes, providing some seven hundred consumers with irrigation water by the turn of the century.30 Unable to store large amounts of water for the frequent dry months in the Boise Valley, this venture had only limited success.

In the early 1880s, led by Arthur D. Foote as engineer, New York, investors set about planning a much larger and more acceptable scheme to irrigate the Boise Valley. Foote surveyed the site and proposed a main canal departing the Boise River east of the city with several lateral ditches connecting to various locations throughout the valley. Financial problems plagued the project from the beginning as several different parties took turns controlling the endeavor. In 1890, hundreds of laborers commenced construction on a canal, named the New York Canal, “bringing renewed hope of large-scale settlement in nearby Bench lands.”31 Within two months, Boise’s population had nearly doubled largely because of the influx of workers and settlers hoping to take advantage of the forthcoming irrigated farmland. Foote planned to accommodate them all by providing water to an impressive half million acres.32 Financial difficulties again delayed the project and Foote pulled out in 1892. In 1899, the New York Canal Company formed to finish the project resulting in a trickle of water passing through in 1900. It was evident that the scheme needed several engineering improvements to generate an effective amount of water downstream. The lack of productivity frustrated local farmers, as the project seemed doomed to come up short of its promised potential. In 1902, however, the United States Government bailed the irrigation project out of futility by providing the funding to improve and finish the venture. The passing of the Reclamation Act allowed for government backed development of the arid West and the Boise Valley benefited as one of the earliest locations to receive this type of assistance. Finally, with the help of the newly formed United States Reclamation Service, a fully functioning canal opened in 1912. Though progress was painfully slow between 1890 and 1912, the promise of irrigation brought new development to the Boise Valley with brisk growth commencing after 1909.33 As part of the plan, now called the Boise Project, workers built a reservoir near Nampa named Deer Flat for storage and a diversion dam east of Boise to carry the water above the Boise Bench. With the construction of Arrowrock Dam upstream a few years later, the valley had a surplus of water allowing for year around irrigation.

The project changed the city of Boise and the Boise Valley by allowing many more and larger farms in areas previously almost completely void of enough water to dampen an average garden. In 1900, with the valley’s farm population at around 1,600, the inadequate water supply meant that the region had met its maximum population and a decline was imminent.34 By 1920, the number of farms had tripled thanks largely to the Boise Project.35 In 1930, the farm population increased to 15,400 and by 1940, 16,000 valley residents inhabited farms.36 Today, Boise Project related irrigation construction is responsible for 276,000 irrigated acres in the Arrowrock division, totaling 8,500 farms.37

With the increase in irrigable property, the city of Boise grew toward the hinterlands absorbing some smaller urban communities and creating others. The abundance of irrigable land brought new inhabitants and development to Boise and the surrounding valley. It is difficult today to imagine the landscape of the Boise without the influence of irrigation. Irrigation allowed Boise to grow in all directions and at elevations previously inaccessible to any substantial amount of Boise River water. Pat Takasugi, Director of the Idaho Department of Agriculture said, “If you look at the ground between here and Mountain Home, the rest of the valley would look like that without the [Boise] project.”38 Certainly urban communities would have been confined to specific areas with only the easiest access to water and little but desert separating them. According to Boise Project Manager Paul Deveau, before irrigation on the Bench, “there were hardly any people here.”39 Between 1880 and 1910, the Boise City population increased from 1,899 to 17,358 a large portion of that due to irrigation related development.40 Deveau attributes much of the appearance and growth of the entire valley, as we know it, to the New York Canal.

Remote agricultural communities were not the only places experiencing growth. The city of Boise reaped the rewards of having water available above the Bench with the development of residential and commercial districts south of the city. Few Boise area maps before around 1910 even acknowledge the existence of inhabitants south of the Boise River and on the Boise Bench. As indicated on a 1917 map of Boise by the Intermountain Map Company, just a few years after the completion of the Boise Project, various agricultural, commercial, and residential developments covered the Boise Bench. Whereas other factors played a part in this development, irrigation provided the foundation for them to build upon.

Railroad Town

Railroads, like irrigation, had a tremendous influence on city growth and development patterns in the decades around the turn of the century. Railroads require large tracts of land usually near city centers. 41 Railroad companies use the land around the railroad for locomotive sheds and other infrastructure while the location near the heart of the city provides for suitable passenger service. Once established, railroads alter nearby land use patterns near the railroad district as well as wherever the rail travels within the city. 42 Besides the supportive infrastructure, warehouses and other large storage related buildings often surround railroad districts. Passenger train depots attracted restaurants, hotels, and saloons providing comfort and relaxation after long trips across, for example, the sparsely populated American West. Finally, land along the tracks exciting city centers often becomes a sort of industrial belt, attracting mostly factories and staving off all but the lowest grade of housing.43 These long stretches of rail-divided cities frequently give rise to a “right” and “wrong” side of the tracks. The two sides usually develop much differently with one becoming home to the less affluent while the other attracts new growth and improvements.

Many communities during the 1800s longed for a railroad connection believing it would “usher in a veritable new age of commerce and industry.”44 Several towns prospered due in large part to rail connections including Denver, Omaha, and Houston, while others such as Leadville, Colorado, and Virginia City, Nevada, failed to do as well without the ability to connect to a mainline.45 With the decline of their local mining industry, both Leadville and Virginia City failed to transform from mining town to railroad town. Boise’s connection to a mainline was not easy to accomplish but the city eventually succeeded in adding railroad town to its growing list of monikers.

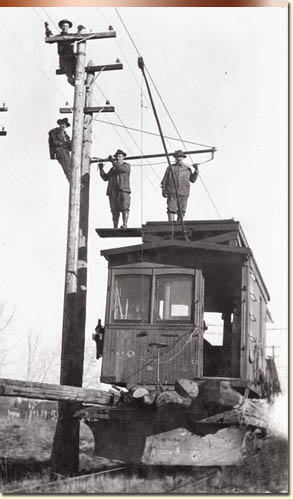

While railroad companies themselves created many towns across the West in the late nineteenth century, Boise had already established itself as a community twenty years before connecting with the Oregon Short Line. Desperately wanting to attach to the mainline of the railroad, the city had to settle for a branch line that linked to an unexceptional depot constructed on the Boise Bench in 1887. Though not located near downtown, the depot did alter the landscape of Boise to some extent. First, the city built a mile long dirt road extending south of town and terminating at the depot. The road included two bridges, one spanning the main channel of the Boise River, and one across a branch stream. Entrepreneurs established a few businesses near the new depot and the city developed a handful of streets behind the terminus including Stewart and Main, not to be confused with the Main Street downtown. F. A. Nourse and P. Sonna built warehouses on Stewart directly behind the depot and overnight guests not wishing to travel into town stayed at the accommodations across the street. If the railroad would not come to Boise, then Boise would come to the railroad.

While some businesspersons gladly set up shop on the Boise Bench, the gap between the city and the railroad upset the balance of the town’s inner workings. The Bench Depot pulled business activity away from the city center much to the chagrin of some city residents. In his book Metropolitan Corridor, John Stilgoe reveals that depots located “a mile or more” from Main Street often relegated the town to “shabbiness.”46 The depot and its location were sadly unacceptable for the citizens of Boise who dreaded the dusty or sometimes muddy one-mile journey to and from “the stub,” a name callously applied by locals.47 Consequently, many rejoiced at the eventual completion of the impressive stone depot erected at 10th and Front Streets nearer the town center. The structure and corresponding tracks, completed in 1893, brought immediate change to the city of Boise as dual tracks entered Boise from the southeast, traveled alongside Front Street through town, and exited the city to the west across a railroad bridge spanning the Boise River.

Immediately warehouses and industrial buildings appeared in the new railroad district. Across the tracks from the depot sat several new lumber companies’ including Ruby Creek Lumber Company, later the Boise-Payette Lumber Company, and a feed and seed establishment later to become a sheet metal business. All along the railway, throughout the city, one found such businesses and a number of industrial units, including a glue factory located west of town next to the river. The most prominent transformation of this type to the city landscape was the establishment of the warehouse district located between Seventh and Ninth Streets, extending three blocks south of Front Street. In the heart of the warehouse district, two branches of the railroad diverged from the main tracks into the alleys between several of the storage facilities and supply stores. From there, trains could easily access the loading docks to pick up or drop off various goods. So significant was the warehouse district to the city geography that many of these buildings still stand and one still produces the same goods, candy, which it did over one hundred years ago.

Unfortunately, the warehouse district also contributed to the decline of nearby residential neighborhoods. As stated earlier, residential areas generally do not do well when located near railroads and this again is evident in Boise. Neighborhoods once known as Miller’s Addition and Riverside Park, and the modern day River Street area were cut off from the rest of Boise to the north by the ever widening path of railroad tracks, soon to number as many as eight across, and to the east by the warehouse district. Coincidently, the once celebrated Grove Street residential area, one block north of the railroad, also experienced a decline during this time as many affluent citizens moved out to Warm Springs and to the North End. The railroad proved detrimental to several other adjacent neighborhoods, resulting in their deterioration. One author wrote of the effect of railroads on neighborhoods that being in the shadow of the railroad “condemned smaller tracts of land to permanent dereliction or blight.”48

Just before the arrival of the downtown depot, the River Street area had developed into a white middle class neighborhood with attractive homes.49 The arrival of industrial related buildings to the area in subsequent years drove out many of the middle class residents as more impoverished inhabitants replaced them.50 Residential areas of lower income, then as now, often did not receive the same attention from investors or political forces resulting in the steady deterioration of the area. Eventually the railroad not only factored into the class structure of Boise but also the racial makeup of certain sections of town. By the 1940’s, the River Street area became one of the few places in town allowable for blacks to rent a home, ultimately establishing the “Black section” of Boise.51 Not until recent decades did this area receive the appropriate attention by the city to rebuild the dilapidated neighborhood.

In keeping with the tradition of the railroad luring specific types of businesses, the vicinity behind the downtown depot attracted several hotels, including four on one block. Restaurants, saloons, and stores also moved adjacent to the depot to be near to the hub of “metropolitan excitement.”52 This area became so dense with development that the Sanborn fire insurance mapmakers labeled the Boise depot area as the “Congested District” for a number of years after the turn of the century.

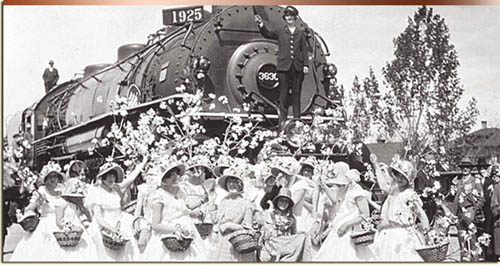

The downtown railroad remained a fixture in Boise well into the 20th century although a connection to the mainline of the Oregon Short Line was what the citizens wanted. In 1925, they got their wish with the construction of a new depot on the Bench not far from where the original stood. The Spanish style depot, together with the Platt Gardens, created a magnificent entryway into the city of Boise. Wanting to connect the impressive new structure with the equally striking State Capitol building, the city set about constructing Capitol Boulevard between the two. What was previously a narrow and dusty road became the grandest street in the city at the time. Boise redrew the city limits to include specifically Capitol Boulevard and the grounds around the new depot. The new Bench Depot influenced the substantial growth on the south side of the Boise River in the coming decades. With the downtown railroad district remaining, much of the industrial and warehouse type districts that railroads attract did not follow the new depot to the Bench. There were occasional storage facilities near the Bench Depot but most of the land on the Bench quickly developed into residential neighborhoods. While, for the most part, wealthier citizens stayed away from settling near the railroad, the homes near the Bench Depot formed respectable neighborhoods for many Boise residents. Predictably, the area along Capitol Boulevard between the depot and downtown attracted hotels, restaurants, and other businesses taking advantage of new arrivals to the city via the railroad. For that reason, the significant growth after 1925 on the south side of the Boise River but below the Bench is also attributable, to some extent, to the Bench Depot and the railroad.

Trolley Town

While heavy rail transported people and passengers into and out of southwestern Idaho, light rail in the form of electric streetcars shuttled individuals around the city and between valley communities. Streetcars, often called trolleys, were essential to suburban development in several cities throughout the country during this time, influencing the direction and rate of growth. Many credit, or blame, streetcars for helping to create some of the early suburbs or satellite communities in cities throughout the Unites States. Real estate developers or boosters often had at least partial ownership in the local streetcar business and manipulated the location of trolley systems ensuring that their real estate ventures were included on the route. According to historian Kenneth Jackson, these land developers were much less interested in the transit fare they received than in their personal development projects. Their goal, according to Jackson, was to “reap the land-speculation profit by dictating…the direction and extent of transportation lines.”53 The resulting “streetcar suburbs” allowed citizens to live in the hinterlands while commuting to the city for work or leisure.

As a result, many cities experienced suburban sprawl decades earlier than that aided by the automobile in the middle of the 20th century. According to one study, beginning in the 1870’s, the electric trolleys of Boston made possible an outward expansion of the city at a rate of ½ to 1½ miles per decade.54 Thanks to shrewd real estate developers, the West experienced similar expansion. In northern California, F. M. Smith developed thirteen thousand acres of land in Oakland and Berkeley in the 1900s with the help of his trolley’s routes.55 Henry Huntington, founder of the Southern Pacific railroad, did the same in the Los Angeles area by buying up and developing land along his trolley lines.56 Accessible transportation with cheap and abundant land lured middle-class families as far as 10 miles away from a given downtown area to often-remote residential neighborhoods.57 In addition to convenient transportation, homeowners near trolley lines benefited from electricity well before other residential areas.58 Streetcars not only transported travelers between home and work but also to and from amusement parks, beaches, and picnic areas.59 Local businesspersons and developers sponsored or owned many of these recreation destinations using them to attract customers or promote new residential districts. These electric trains traveled as fast as fourteen miles per hour, enabling the existence of a “new city” encompassing an area triple the size of the previous walkable city.60 With Boise, there is evidence of citizen interchange between several points within the valley resulting in enormous influence over the shape, direction, and rate of the city’s growth.

Boise’s electric trolley service began operation 1891 as the Boise Valley Interurban; just two years after Frederick Sprague installed a working electric streetcar system in Richmond, Virginia.61 The inventor proclaimed the “electric railway…the most potent factor in our modern life.”62 For a number of years separate trolley companies competed for business in the Boise Valley before merging in 1912 as the Idaho Traction Company. At their peak, electric trolley tracks traveled through several downtown streets including, but not limited to, Main, Bannock, State, 7th, 8th, and 13th. By examining a map of 1917 Boise, one can follow the trolley lines east along Warm Springs Avenue, south across the Broadway Bridge deep into south Boise, west to the fair grounds, and north into the many North End subdivisions. Clearly, the Boise trolley systems reached nearly all corners of the city, enabling passenger access to and from almost anywhere.

By 1912, the Idaho Traction Company completed the Boise Valley Loop. The trolley loop traveled on the north side of the Boise River through Eagle, Star, and Middleton before crossing the river into Caldwell. From there the path made several stops on the way to Nampa, and then journeyed to Meridian and back into Boise. There were remote stops or “intermediate points” as well between the larger towns to pick up the more rural customers. With access to anywhere on the loop, from anywhere on the loop taking between thirty to ninety minuets, citizens found living in remote subdivisions or communities suitable.63

Contemporary maps show clear evidence of the inter-reliance between Boise subdivisions and the electric trolley system. A relationship undoubtedly existed between trolleys and neighborhoods like Stein’s Addition, Eagleson’s Park Addition, Altura Park, and the Hillcrest Addition south of Overland between Latah and Broadway. The arrangement of these South Boise subdivisions unmistakably followed the trolley lines closely on either side. It is also apparent that residential developments flourished on route to trolley recreation destinations like the Natatorium swimming pool and Pierce Park. Even the most remote areas along State Street developed directly because of trolley access and nowhere in Boise did the streetcar system have more influence than in the North End.

As stated earlier, many of the individuals involved in real estate were also interested in the trolley business and Boise was no different. Familiar Boise names like Pierce, Lemp, and Sonna considered the trolley beneficial to other business interests. In fact, because the trolleys themselves were not very profitable, it is apparent that they were more of a tool to promote the subdivisions, recreation sites, and other businesses owned by these same men. This was not just a Boise phenomenon. In 1918, the Massachusetts Street Railway Commission stated, “It is a well known fact that real estate served by adequate street railway facilities is more readily saleable and commands a higher price than real estate not so served.”64 In Calgary, Max Foran showed that the presence of street railway had a direct effect on predicting growth. This relationship was evident to Boise businesspersons as the Pierce Real Estate Company, for example, held rights for an electric streetcar north of town hoping, correctly, that the trolley would spur a real estate boom in the North End.65 Pierce and company used the trolley system heavily in promotion of their many real estate developments throughout the years of its existence.

By 1928, the popularity of the automobile had ended electric streetcars in Boise though their influence on the organization of the Boise Valley is unquestionable. The trolley helped make living in remote residential areas a reasonable situation for many valley citizens. Communities like the North End, South Boise, Yost, Ustick, and Collister could never have flourished as they did if not for the trolley system. Boise, as well, benefited from the exchange of commerce between the city and these remote villages in the valley. It is not as easy today to see the impact of trolleys on the city shape, but a century ago, the streetcar lines and residential development went hand in hand.

Idyllic Settlement

While the influence of large tangible entities such as railroads and trolleys on cities is often unmistakable, individuals sometimes overlook the impact of maps themselves. City promoters and businesspersons used maps extensively in the nineteenth-century in order to exhibit boundaries and lay claim to specific tracts of land, chart or plan future development, and promote cities as a promising, prosperous, and beautiful place to relocate. Because maps are simply a representation of reality, they depict only selected features and the relationships between those features. Sponsors and producers of promotional maps portrayed their subjects primarily in a flattering fashion with the hope that the representation would attract investors and settlers to their community. One of the most popular categories of promotional maps in the late 1800s was that of the bird’s-eye-view artistic images of American towns. Artists used several methods in order to create these images with lithographic depictions as the most fashionable.

Lithography was a quick and inexpensive way to produce printed images resulting in thousands of urban views published between 1825 and 1900.66 The settlement of the American West and inevitable founding of new towns created several new subjects for artists to draw. Interested parties, usually businesspersons from the city in question, often commissioned city drawings from artists who then relinquished the representation to lithographers because of the simplicity of duplicating the finished version. The city promoters then used the prints to publicize their city as picturesque, modern, and with plenty of room for more development.

Towns throughout the United States and specifically the American West utilized maps in their promotional campaigns with varying results though their popularity indicates at least moderate success. Artists ensured that each portrayal emphasized the town’s strengths while ignoring any deficiencies. An 1868 view of Omaha emphasized development on the nearby Missouri River, while also drawing attention to the city’s designation as the eastern terminal of the Union Pacific.67 An 1869 lithograph of Hannibal, Missouri, accentuated the same by placing both the railroad and Mississippi River prominently in the foreground.68 It was common to display the city’s transportation capabilities, resources, sophistication, and opportunity for expansion.

Promoters circulated bird’s-eye-view maps by numerous means. Newspapers sometimes displayed them at times to coincide with a given story or to promote their own town. A Seattle journalist, in 1884, backed a Henry Wellge lithograph of the city by stating, it “will be a splendid thing to send abroad to advertise the town.”69 Real estate developers distributed them, as did interested railroad companies and other businesspersons. In 1885, the Northern Pacific Railroad platted three thousand acres to create Yakima, Washington, and likely commissioned the lithographic view created four years later in order to attract new residents and stimulate real estate sales.70 Concerning an 1891 lithograph of Denison, Texas, the local newspaper reported that every person should own at least one copy and that businesspersons should purchase several copies to distribute as advertisement.71 A Pittsburgh newspaper as well proclaimed that an 1849 lithograph by Edwin Whitefield would give those around the country a “proper conception” of the “size of this city and environs.”72

It is not surprising that lithographs and other perspective maps of the relatively small city of Boise exist as artists created thousands, utilizing towns of all sizes, during the nineteenth century. Other Idaho, towns used as subjects include Atlanta, Custer, Hailey, Moscow, Quartzburg, Rocky Bar, and Silver City. Artists created at least five aerial view maps of Boise during the late 1800s of varying quality and detail.

One of the earliest depictions of Boise is the lithograph “Boise City: Principal Businesses, Houses, and Private Residences” created in 1878 by Austrian born Charles Ostner. In 1881, an unknown artist created a similar map entitled “Boise City and Valley, from Fort Boise, 1881” while renowned German lithographic artist Augustus Koch produced probably the most magnificent view with “Bird’s-Eye-View of Boise City, Ada County, the Capital of Idaho, 1890.” Koch’s unusual style of drawing cities as if they were located on a steeply tilted plane allowed him to depict the buildings in the background almost as large as those in the foreground.73 Two other representations, “View of Boise City from Courthouse, 1883” and “View of Boise City, 1890,” render the city from a much closer observation point.

While varying slightly on vantage point, detail, and quality, all of these maps have traits in common with each other as well as with other maps of this genre and time period. All of them depict Boise from the north looking south. Viewing the city from the opposite direction might have excluded the river and revealed much less room for expansion due to the obstruction provided by the nearby foothills. All emphasize the beauty and “natural” setting of the city by presenting things like mountains in the background, the Boise River, and the prominence of trees within the city. By also featuring prominent business buildings, brilliantly designed modern homes, and an organized street system, artists illustrated a progressive urban area but with plenty of room for additional growth.

Boise certainly benefited from these maps as well as other promotional tools that often corresponded with them. Local real estate developer W. E. Pierce utilized maps, photographs, and drawings in order to give a visual representation of the city written so eloquently of in his promotional publications. In the 1893 publication produced by W. E. Pierce and Company, the land speculators wrote, “In a lovely valley, just where the mountains rise to conceal and protect the immense treasures…lies Boise City.”74 The booklet continued with its description of the Boise River as, “a wide and rapid stream.”75 While the words painted a pleasant enough picture, visual representations contributed to the overall package, particularly when completed in lithographic map format by skilled and knowledgeable artists.

Clearly, without the benefits of being a port city, environmental paradise, or major trade center, Boise survived and occasionally thrived in a time when other cities struggled. Founded in a somewhat indistinct location, the city reinvented itself periodically in order to continue to expand and resisted the temptation to rely on past accomplishments. Astute businessmen, always searching for ways to profit from westward expansion, relentlessly pushed for new economic ventures, consequently allowing Boise to progress rather than stagnate. Beginning as a mining town, Boise grew quickly as a trade and supply center. Later, irrigation brought workers and settlers to Boise and allowed previously barren earth to become valuable and fertile farmland. This opened much more territory for settlement and expanded Boise’s urban area west and to the south above the Boise Bench. Unable to obtain a mainline connection to the railroad for a number of years, the city formed around branch links on the Boise Bench and downtown. Both locations, along with the eventual mainline depot, changed the city landscape near the railroad stations as well as along the many tracks extending from them. The trolley system, also an extensive rail system, transformed Boise and the surrounding area by promoting growth into the streetcar suburbs and other small satellite communities within the valley. Residents found that they could live away from the city center and continue to enjoy the advantages of urban life. The electric streetcars helped to develop residential areas in all directions around Boise and encouraged leisure and business travel between the valley’s communities. Finally, city promotion in the form of bird’s-eye-view maps permitted boosters a format in which to display all in which the city offered. In an era of little or no mass communication, these maps gave city promoters a unique way in which to attract visitors, investors, and settlers to their town.

While not an exhaustive list of growth influences, these factors helped to physically shape Boise growth considerably during the first seventy years of its existence. Boise failed to continue reinventing itself following the Great Depression as it and most other cities struggled to survive. While the population continued to grow at a slow but steady rate, the city understandably seemed content with the status quo. In recent years, the Boise Valley is again booming. Perhaps not so coincidently, the city has also conceived new ways in which to categorize itself. Beginning in the 1960s with the clean up of and ensuing development along the Boise River, we see the emergence of Boise the “River City.” With the emergence of Micron, HP, and other electronic related companies, Boise materialized into Boise an “Industrialized City.” In addition, Boise heavily promotes other facets of its identity including those pertaining to outdoor recreation and Boise State University. Whether or not people someday refer to Boise primarily known as a “College Town” or “Recreation Destination” remains unknown but it is certain that if the past is any indicator, diversification of identity can influence city success in significant fashion.

Bibliography

Locating and handling maps for this project proved at times more difficult than first imagined. While finding maps of Boise and the surrounding area is far from challenging, finding and obtaining the appropriate maps happened to be much more so. The Idaho State Library and Archives, the Boise Public Library, Albertson’s Library at Boise State University, the Boise City Archives, and the Sanborn Map Company each assisted greatly with the task of acquiring copies or digital images of often old and fragile documents. The Idaho State Library and Archives has a large number of fine maps available and for a nominal fee, they will copy them. The Boise Public Library maintains a collection of historical maps and though they are not always available for casual browsing, the staff is more than willing to dig up requested documents. The Sanborn Map Company has much of their collection available online though it may not be available unless accessed through a subscribing institution such as a local university. Albertson’s Library at Boise State University possesses maps readily accessible for perusing and they are available for checkout by students and faculty. Finally, the City of Boise has a wonderful collection of historical maps in their archives though they are still working on organizing and labeling them so research may require a bit of digging. The City Clerk’s office can scan and save them on a compact disk if requested.

Many of the maps were too large to scan with the average home scanner and required much larger equipment owned by the City of Boise, the Idaho State Historical Society, or a local copy store. In addition, the brittleness of some of the older maps forced the use of a digital camera rather than risk running them through a scanner. Once in digital form, the shear size of some of the files required a great deal of trial and error with different software in order to find the best for managing and preparing the images for display. In the end, a combination of software titles, computers, and data storage devices allowed for workable images.

Secondary Sources

Bird, Annie Laurie. Boise: The Peace Valley. Caldwell: Caxton Printers, 1934.

Casner, Nick and Valeri Kiesig. Trolley: Boise Valley’s Electric Road 1891-1928. Boise: Black Canyon Communications, 2002.

Cronon, William. Nature’s Metropolis: Chicago and the Great West. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 1991.

Harper Collins. Past Worlds: Collins Atlas of Archaeology. Ann Arbor: Borders Press, 2003.

Idaho State Historical Society Reference Series. #171.

Idaho State Historical Society Reference Series. #190.

Idaho State Historical Society Reference Series. #220.

Idaho State Historical Society Reference Series. #363.

Jackson, Kenneth T. Crabgrass Frontier: The Suburbanization of the United States. New York: Oxford University Press, 1985.

Jacobs, Jane. The Economy of Cities. New York: Random House, 1969.

Knox, Paul L. Urbanization: An Introduction to Urban Geography. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 1994.

Larsen, Lawrence H. The Urban West at the End of the Frontier. Lawrence, Kansas: The Regents Press of Kansas, 1978.

MacGregor, Carol Lynn. Founding Community in Boise, Idaho, 1882-1910. Dissertation for PhD. University of New Mexico, 1999.

McCarter, Brian. A Rebuilding Process for River Street Neighborhood Boise, Idaho. Eugene, Oregon: University of Oregon Department of Landscape and Design, 1975.

Moffat, Riley. Population History of Western U.S. Cities and Towns, 1850-1990. Lanham, Md., and London: The Scarecrow Press, 1996.

Pierce, W. E. & Company. Boise City, Idaho Illustrated. Boise: W. E. Pierce & Company, 1893.

Reader, John. Cities. New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 2004.

Reps, John. Cities on Stone: Nineteenth Century Lithograph Images of the Urban West. Fort Worth: Amon Carter Museum, 1976.

________. Panoramas of Promise: Pacific Northwest Cities and Towns on Nineteenth Century Lithographs. Pullman: Washington State University Press, 1984.

Russo, David J. American Towns: An Interpretive History. Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2001.

Stacy, Susan M. When the River Rises: Flood Control on the Boise River 1943-1985. Boise: Boise State University College of Social Sciences and Public Affairs, 1993.

Stilgoe, John R. Metropolitan Corridor: Railroads and the American Scene. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1983.

Wells, Merle and Arthur A. Hart. Boise: An Illustrated History. Sun Valley, CA: American Historical Press. 2000.

Newspapers

The Idaho Statesman, 1863-Present.

Maps

Boise City Archives map collection.

Boise Public Library map collection.

Boise State University map collection.

Idaho State Library and Archives map collection.

Sanborn Map Company.

Endnotes

1 Annie Laurie Bird, Boise: The Peace Valley, (Caldwell: Caxton Printers, 1934), 14. A good source for the origin of the name “Boise” is the Idaho State Historical Society Reference Series, Number 32, “The Name ‘Boise’.”

2 William Cronon, Nature’s Metropolis: Chicago and the Great West, (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. 1991), 33-34.

3 Ibid., 35.

4 Ibid., 36.

5 Jane Jacobs, The Economy of Cities, (New York: Random House, 1969), 141.

6 Ibid., 34.

7 Lawrence H. Larsen, The Urban West at the End of the Frontier, (Lawrence, Kansas: The Regents Press of Kansas, 1978), 19.

8 John Reader, Cities, (New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 2004), 73.

9 Ibid., 74.

10 Ibid., 73.

11 Bird, 169. More about the location of Fort Boise and the city of Boise can be found in the Idaho State Historical Society Reference Series Number 1119, “Location of Fort Boise and Boise City.”

12 Ibid., 168.

13 Ibid.

14 Ibid., 187.

15 Ibid., 189. The 1863 H.C. Riggs map “Plat of Boise City,” depicts the names of each person on the appropriate lot within the newly established town. Copies of this map are available from the Idaho State Historical Society as well as several publications including An Atlas of Idaho Territory 1863-1890, by Merle Wells.

16 Ibid., 190.

17 Idaho State Historical Society, “Boise City Urban Area Population, 1863-1980,” Reference Series #363.

18 David J. Russo, American Towns: An Interpretive History, (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2001), 37.

19 Ibid., 294.

20 Ibid., 37.

21 Larsen, 14.

22 Ibid.

23 Russo, 70.

24 Riley Moffat, Population History of Western U.S. Cities and Towns, 1850-1990, (Lanham, Md., and London: The Scarecrow Press, 1996), 94-97.

25 Carol Lynn MacGregor, Founding Community in Boise, Idaho, 1882-1910, (Ph.D. diss., University of New Mexico, 1999), 53.

26 Idaho State Historical Society, “Early Irrigation Canals Pre-Project Ventures,” Reference Series #171.

27 Ibid.

28 MacGregor, 54.

29 Susan M Stacy, When the River Rises: Flood Control on the Boise River 1943-1985, (Boise: Boise State University College of Social Sciences and Public Affairs, 1993), 6.

30 ISHS Reference Series #171.

31 Merle Wells and Arthur A. Hart, Boise: An Illustrated History, (Sun Valley, CA: American Historical Press, 2000), 56.

32 Idaho State Historical Society, “The Beginning of the New York Canal,” Reference Series #190.

33 Wells, 58.

34 Stacy, 9.

35 Ibid. For more on the Boise Project, please see Idaho Issues Online, Fall 2006. There is a concise article by Kathleen Craven entitled “Boise Project.” Another good source is Neil H. Carlton “A History of the Development of the Boise Irrigation Project.” Unpublished M.A. thesis, Brigham Young University, 1969.

36 ISHS Reference Series #171.

37 Kathleen Mortensen, “From Desert to Oasis,” The Idaho Statesman, 14 March 1999, sec. 1A, 4A.

38 Ibid.

39 Ibid.

40 Moffat, 90.

41 Paul L. Knox, Urbanization: An Introduction to Urban Geography, (Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 1994), 82.

42 Ibid.

43 Ibid., 84.

44 Larsen, 99.

45 Ibid., 106.

46 John R. Stilgoe, Metropolitan Corridor: Railroads and the American Scene, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1983), 193.

47 Arthur Hart, “When the Depot was right Downtown,” The Idaho Statesman, 18 October 2005, sec. Life, p. 3.

48 Knox, 84.

49 Brian McCarter, A Rebuilding Process for River Street Neighborhood Boise, Idaho, (Eugene, Oregon: University of Oregon Department of Landscape and Design, 1975), 3.

50 Ibid.

51 Ibid., 4.

52 Stilgoe, 193.

53 Kenneth T. Jackson, Crabgrass Frontier: The Suburbanization of the United States, (New York: Oxford University Press, 1985), 120.

54 Ibid., 118.

55 Knox, 91.

56 Ibid., 92.

57 Ibid., 89.

58 Nick Casner and Valeri Kiesig, Trolley: Boise Valley’s Electric Road 1891-1928, (Boise: Black Canyon Communications, 2002), 12.

59 Knox, 90.

60 Jackson, 115.

61 Idaho State Historical Society, “Boise Valley Electric Railroads,” Reference Series #220. For more on Idaho trolleys see William G. Dougall, “Clang, Clang, Clang Went the Trolley,” Idaho Heritage, (SeptemberOctober, 1976), 1417.

62 Jackson, 115.

63 ISHS Reference Series #220.

64 Jackson, 120.

65 Casner, 53.

66 John Reps, Cities on Stone: Nineteenth Century Lithograph Images of the Urban West, (Fort Worth: Amon Carter Museum, 1976), 2. John Reps has written several very good books about lithographs and city planning including Views and Viewmakers of Urban America: Lithographs of Towns and Cities in the United States and Canada, Notes on the Artists and Publishers and a Union Catalog of their Work, 1825-1925, (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1984.

67 Ibid., 16.

68 Ibid.

69 John Reps, Panoramas of Promise: Pacific Northwest Cities and Towns on Nineteenth Century Lithographs, (Pullman: Washington State University Press, 1984), 9.

70 Reps, Panoramas of Promise, 8.

71 Reps, Cities on Stone, 31.

72 Ibid.

73 Reps, Panoramas of Promise, 8.

74 W. E. Pierce & Company, Boise City, Idaho Illustrated, (Boise: W.E. Pierce & Co., 1893), 3.

75 Ibid.