Social Behavioral Sciences

Kiana Nygaard, Dr. Megan L. Smith

Introduction

Experiencing physical violence has been shown to have a large impact on mental health leading to issues such as Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), substance abuse, and depression such as what is found by Cisler et. al (2012). Much of the existing research on being a victim of physical violence has focused on the outcomes associated with PTSD. However, this study was specifically interested in the link between depression and experiencing physical violence.

Research suggests that there are gender differences in physical violence and depression experiences. Dunn et al. (2012) found that although male and female depression was equally impacted by experiencing violence, females are at a higher risk for depression because, compared to males, they had a higher chance of experiencing violence. Some studies such as one by Heinze et al. (2018) have investigated experiencing physical violence in childhood and the impact on adult outcomes of mental health. A greater look at how violence affects adolescent depression is needed as well as the potential temporal impacts. One study that investigated temporal impacts looked at the same day and next day effects of violence on adolescents’ mental health and found that exposure to violence significantly increased the likelihood of experiencing depression, anger, and irritability on the same day and next day (Suliman et. al, 2009).

The current study seeks to build on this existing research by looking at proximity effects of experiencing physical violence on depression and uses a larger time scale, including violence experienced over a year ago.

Methods

Participants:

Data was collected from adolescents grades 5-12 N= 13,736. Of that, 6,304 were in middle school and 7,217 were in high school. 49.5 percent of students identified as male, 48.7 percent as female, while the remaining 1.8 percent identified as other. Of the 13,736 students, 9,181 students had data available on both variables of interest and were included in this analysis.

Procedures:

Students took a survey during school in one of their classes. The survey was administered by their teacher. Surveys were taken either

on paper or in a computer lab. The study was approved by the IRB at a major university.

Measures:

Depression was measured using the SCL-90 which is a validated clinical tool used to diagnose depression symptoms. Students were asked how often if ever they experienced symptoms such as nervousness. They were given four options 1=never, 2=seldom, 3=sometimes, 4=often.

Violence proximity was measured in four different groups (in the last 30 days, in the last 12 months, more than 12 months ago, and never) based on their response to “Have you ever experienced physical violence by an adult?”

Data Analysis:

A one-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was conducted to compare the effect of violence proximity to depression outcomes.

Results

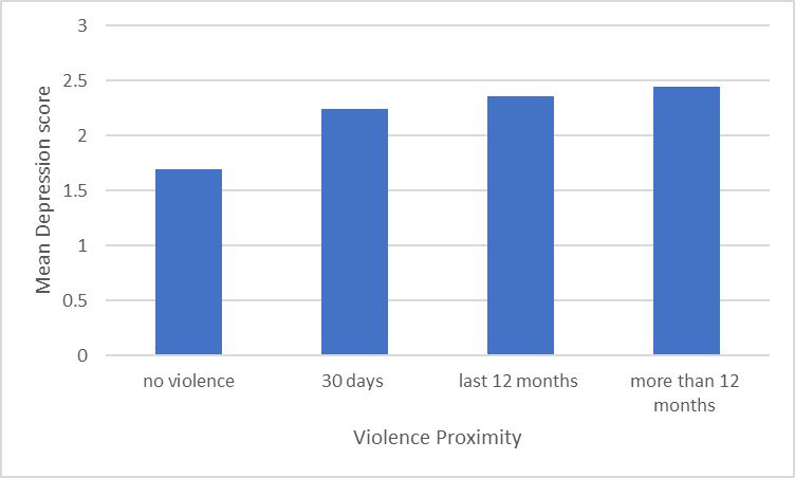

An analysis of variance showed that the effect of violence proximity and experiencing depression was significant at the p<.05 level, F(4,9176)= 119.28. The group who had the highest depression score had experienced violence more than twelve months ago (m=2.44), followed by in the last 12 months (m=2.36), last 30 days (m=2.41), and as expected no violence had the lowest mean depression score (m=1.69).

Discussion

Results indicate that mean depression scores increase with time passed after experiencing physical violence. Adolescents experiencing violence over 12 months ago had the highest depression score while those who had not experienced any violence had the lowest depression score. This is consistent with findings showing that violence has a negative impact on mental health. The fact that depression scores increased as proximity decreased could suggest that past instances with violence are just as important to focus on as current ones. Additionally, these findings could indicate that physical violence that happens over time could create greater depression, because this was cross-sectional, we are unable to substantiate this notion, but it is an important idea to investigate. It is also important to note that although results showed a significant difference across all groups, the mean scores differ by a small

amount which may indicate that these significant differences are not meaningful in practice.

Limitations & Future Directions:

For those who experienced violence over 12 months, ago the specific age at which it occured is not known which could have given the study insight into if there is a certain age range in which children are impacted more. Also it is not known who perpetrated the violence only that it was an adult, it could be useful to determine if certain types of perpetrators have a greater impact on adolescents’ depression outcomes. Finally, this study was cross sectional so it is not possible to determine if depression is chronic or acute or how frequent (or how long) the physical violence occurred. If a longitudinal study was conducted, it would also allow us to see how long depressive symptoms continued and the role that frequency played on them.

Conclusions/Implications:

It was shown that adolescents having experienced violence over 12 months ago had the highest mean depression score. This indicates that past traumas should not be written off as insignificant because they are distant from the present and adolescents should still be receiving support.

Additional Information

For questions or comments about this research, contact Kiana Nygaard at kiananygaard@u.boisestate.edu.