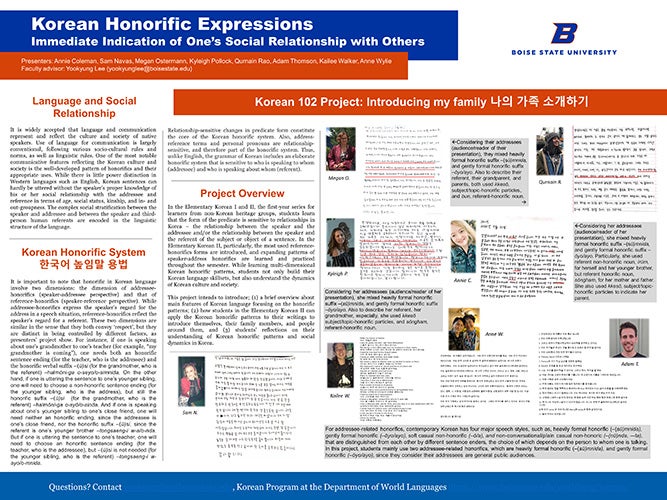

Immediate Indication of One’s Social Relationship with Others

Megan Ostermann, Annie Coleman, Sam K. Navas, Kyleigh Pollock, Qurnain Rao, Adam Thomson, Kailee Walker, Hailey Windley, Anne Wylie, Jungmi Woo, Dr. Yookyung Lee

Language and Social Relationship

It is widely accepted that language and communication represent and reflect the culture and society of native speakers. Use of language for communication is largely conventional, following various socio-cultural rules and norms, as well as linguistic rules. One of the most notable communicative features reflecting the Korean culture and society is the well-developed pattern of honorifics and their appropriate uses. While there is little power distinction in Western languages such as English, Korean sentences can hardly be uttered without the speaker’s proper knowledge of his or her social relationship with the addressee and reference in terms of age, social status, kinship, and in- and out-groupness. The complex social stratification between the speaker and addressee and between the speaker and third-person human referents are encoded in the linguistic structure of the language.

Korean Honorific System

한국어 높임말 용법

It is important to note that honorific in Korean language involve two dimensions: the dimension of addressee-honorifics (speaker-addressee perspective) and that of reference-honorifics (speaker-reference perspective). While addressee-honorifics express the speaker’s regard for the address in a speech situation, reference-honorifics reflect the speaker’s regard for a referent. These two dimensions are similar in the sense that they both convey ‘respect’, but they are distinct in being controlled by different factors, as presenters’ project show. For instance, if one is speaking about one’s grandmother to one’s teacher (for example, “my grandmother is coming”), one needs both an honorific sentence ending (for the teacher, who is the addressee) and the honorific verbal suffix –(ŭ)si (for the grandmother, who is the referent) –halmŏni-ga o-seyo/o-simnida. On the other hand, if one is uttering the sentence to one’s younger sibling, one will need to choose a non-honorific sentence ending (for the younger sibling, who is the address), but still the honorific suffix –(ŭ)si (for the grandmother, who is the referent) –halmŏni-ga o-syŏ/o-sinda. And if one is speaking about one’s younger sibling to one’s close friend, one will need neither an honorific ending, since the addressee is one’s close friend, nor the honorific suffix –(ŭ)si, since the referent is one’s younger brother –tongsaeng-i w-a/o-nda. But if one is uttering the sentence to one’s teacher, one will need to choose an honorific sentence ending (for the teacher, who is the addressee), but –(ŭ)si is not needed (for the younger sibling, who is the referent) –tongsaeng-i w-ayo/o-mnida.

Relationship-sensitive changes in predicate form constitute the core of the Korean honorific system. Also, address-reference terms and personal pronouns are relationship-sensitive, and therefore part of the honorific system. Thus, unlike English, the grammar of Korean includes an elaborate honorific system that is sensitive to who is speaking to whom (addressee) and who is speaking about whom (referent).

Project Overview

In the Elementary Korean I and II, the first-year series for learners from non-Korean heritage groups, students learn that the form of the predicate is sensitive to relationships in Korea – the relationship between the speaker and the addressee and/or the relationship between the speaker and the referent of the subject or object of a sentence. In the Elementary Korean II, particularly, the most used reference-honorifics forms are introduced, and expanding patterns of speaker-address honorifics are learned and practiced throughout the semester. While learning multi-dimensional Korean honorific patterns, students not only build their Korean language skillsets, but also understand the dynamics of Korean culture and society.

This project intends to introduce; (1) a brief overview about main features of Korean language focusing on the honorific patterns; (2) how students in the Elementary Korean II can apply the Korean honorific patterns to their writings to introduce themselves, their family members, and people around them, and (3) students’ reflections on their understanding of Korean honorific patterns and social dynamics in Korea.