Modeling Prehistoric High Altitude Camps in the Great Basin

Julie Julison, Dr. Pei-Lin Yu

Research Question

In many of the low elevation areas in the Great Basin between the Middle Archaic (5,000-1,000 B.C.) and the Late Archaic period (1,000 B.C. to A.D. 500.) there were significant climatic changes that occurred which shifted food procurement strategies from hunting to plant intensification. This report re-examines prior archaeological data to determine if the same subsistence strategies extend to high altitude environments during the same time periods (Figure 1).

Background

Some high altitude locations have distinct features and diagnostic projectile points that suggest a Middle Archaic time period, along with a Late Archaic component which includes dwellings and a much broader diverse artifact assemblage.

By looking at faunal remains and plant materials in food contexts we can suggest what people were eating.

Methods

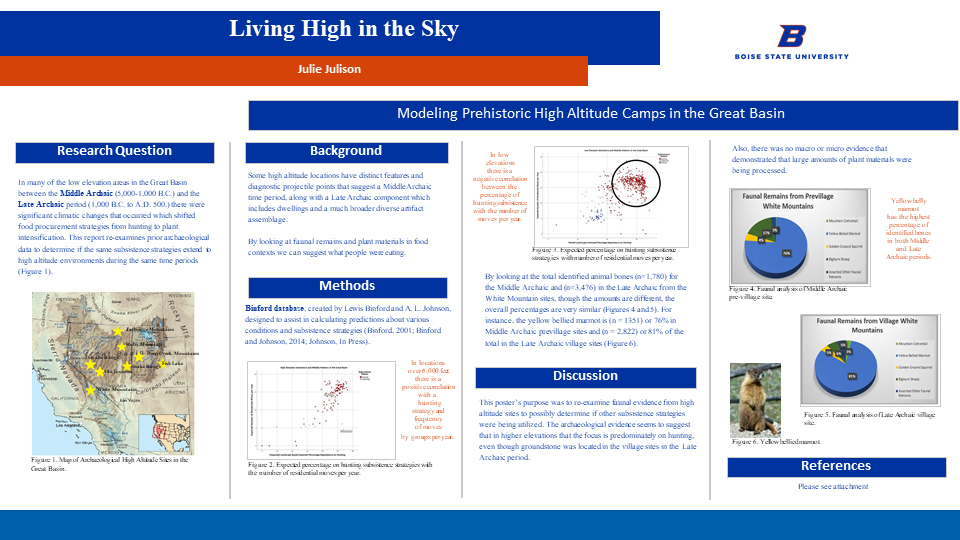

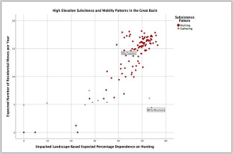

Binford database, created by Lewis Binford and A. L. Johnson, designed to assist in calculating predictions about various conditions and subsistence strategies (Binford, 2001; Binford and Johnson, 2014; Johnson, In Press).

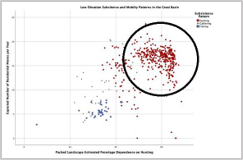

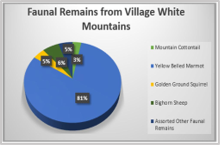

By looking at the total identified animal bones (n=1,780) for the Middle Archaic and (n=3,476) in the Late Archaic from the White Mountain sites, though the amounts are different, the overall percentages are very similar (Figures 4 and 5). For instance, the yellow bellied marmot is (n = 1351) or 76% in Middle Archaic previllage sites and (n = 2,822) or 81% of the total in the Late Archaic village sites (Figure 6).

Discussion

This poster’s purpose was to re-examine faunal evidence from high altitude sites to possibly determine if other subsistence strategies were being utilized. The archaeological evidence seems to suggest that in higher elevations that the focus is predominately on hunting, even though groundstone was located in the village sites in the Late Archaic period.

Also, there was no macro or micro evidence that demonstrated that large amounts of plant materials were being processed.

References

- Bettinger, Robert L. 1976 The Development of Pinyon Exploitation in Central Eastern California. The Journal of California Anthropology Vol 3 (1) pp. 81-95.

- 1991 Aboriginal Occupation at High Altitude: Alpine Villages in the White Mountains of

Eastern California. American Anthropologist. Vol. 93 (3): pp.656-679. - Binford, L. R. 2001 Constructing Frames of Reference: An Analytical Method for Archaeological Theory Building Using Hunter-Gatherer and Environmental Data Sets. University of California

Press, Berkeley, CA. - Binford, L. R., and A. L. Johnson. 2014 Program for Calculating Environmental and Hunter-Gatherer Frames of Reference. (ENVCALC2.1). Updated Java Version, August, 2014.

- Grayson, Donald, K. 1989 Bone Transport, Bone Destruction, and Reverse Utility Curves. Journal of Archaeological Science. Vol 16: pp. 643-652.

- 1990 Alpine Faunas from the White Mountains, California: Adaptive Change in the Late

Prehistoric Great Basin? Journal of Archaeological Science. Vol 18: pp. 483-506. - Johnson, A. L. In Press. Using Frames of Reference: A Guide to Binford’s Datasets, Program, and Their Research Potential. Truman State University Press, Kirksville MO.

- Rhode, David, and David B. Madsen 1998 Pine nut use in the early Holocene and beyond: the Danger Cave Archaeobotanical record. Journal of Archaeological Science. 25: pp. 1199-1210.

- Scharf, Elizabeth A. 2009 Foraging and Prehistoric Use of High Elevations in the Western Great Basin: Evidence From Seed Assemblages at Midway (CA-MNO-2196). Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology. Vol. 29, (1): pp. 11-28.

- Thomas, D. H. 2014 Alta Toquima: Why Did Foraging Families Spend Summers at 11,000 Feet? In Nancy Parezo and Joel Janetski (Eds.) Archaeology in the Great Basin and Southwest. The University of Utah Press. Salt Lake City, UT. pp. 130-148.

Additional Information

For questions or comments about this research, contact Julie Julison at juliejulison@u.boisestate.edu.