Todd Shallat, Ph.D., is professor emeritus of history and urban studies at Boise State University.

Humanity’s most contagious moments touch off the bizarre and unexpected through the aftershock chain reactions of seemingly unrelated events. Inspired by COVID-19, in the categories of politics, science, war, literature, and visual arts, we offer 19 pandemic queries.

POLITICS

Question 1

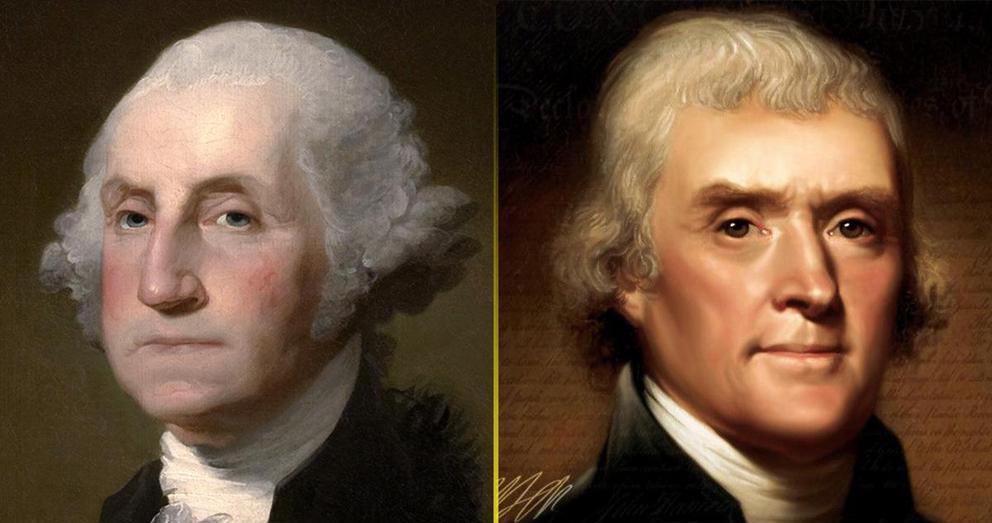

The epidemic helped forge the American two-party system. In Philadelphia, as the death toll mounted, Federalists accused Democrats of a biological terror campaign.

A. Smallpox

B. Great Plague of Marseille

C. Yellow fever

D. Plague of Justinian

Answer: C

In 1793 a slave revolt in the French colony of Saint-Domingue (Haiti) sent yellow fever to Philadelphia with thousands of French refugees. The party of George Washington, called Federalists, alleged that Thomas Jefferson and the Democrats had conspired with France to infect the capital city, poisoning its public wells.

Question 2

In February 1692, in the Massachusetts village of Salem, eight young women accused their neighbors of witchcraft. Some historians blame the hysteria on a viral fever spread by insects and birds.

A. Bird flu

B. Encephalitis

C. Typhoid

D. Yellow fever

Answer: B

Brain-swelling Encephalitis lethargica swept Massachusetts during the 1692 season of the notorious witchcraft trials. Girls from the village of Salem suffered from tremors and feverish hallucinations. Doctors blamed demonic possession.

Question 3

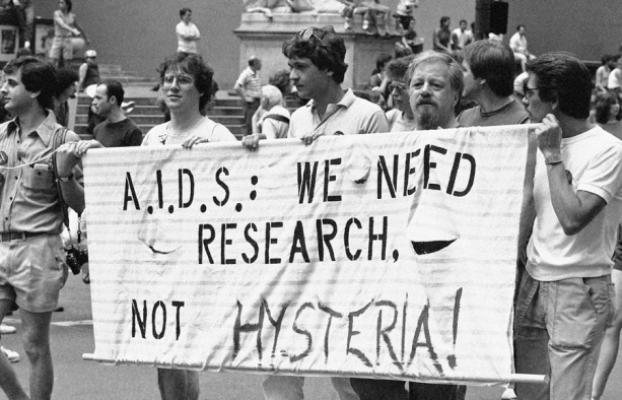

“We are fighting a disease, not people,” said Surgeon General C. Everett Koop. Americans would have to learn not to scorn a population of victims not exactly considered mainstream.

A. West Nile virus

B. Zika

C. Opioids

D. HIV/AIDS

Answer: D

AIDS hit America in 1969. Not until 1986 did a U.S. president address the subject. Ronald Reagan’s surgeon general took the lead in calling for testing, sex education, and research funds.

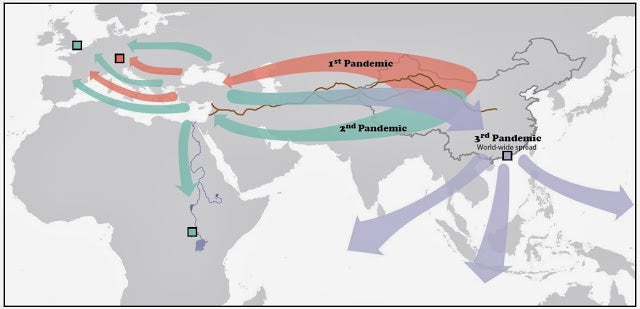

Question 4

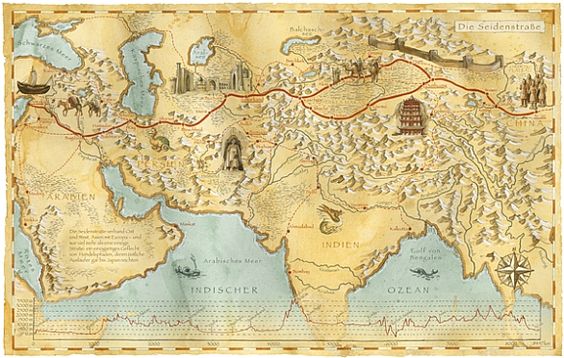

A trade deal with China unleashed one of the deadliest of the great pandemics. Italy was hit especially hard.

A. Plague of Justinian

B. Ganges River cholera

C. Bubonic plague

D. COVID-19

Answer: C

Marco Polo’s Silk Road to China transported the bubonic plague via the fleas on humans and rodents. In 1346, reaching Venice, the plague spread through shipyards and trade routes. An estimated 100 million Europeans died.

SCIENCE

Question 5

A London doctor used a dot map to pioneer the modern science of epidemiology.

A. Third cholera pandemic

B. Great Plague of London

C. Typhus “Irish fever”

D. Diphtheria

Answer: A

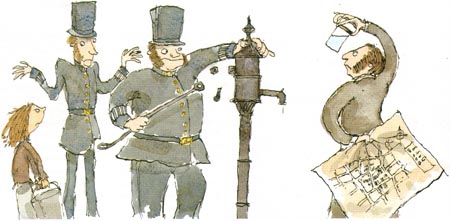

The third cholera epidemic hit London in 1853. John Snow, a local physician, traced the source of the cholera to a public pump where a pail of water had been used to launder a child’s diaper.

Question 6

Scientists blamed stressed-out bats and their habitat loss for this 21st century pandemic.

A. COVID-19

B. Ebola

C. SARS

D. All of the above

Answer: D

Horseshoe bats from a remote cave in China’s Yunnan province may have transmitted severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). Ebola’s patient zero may have been a bat-infected 18-month-year-old boy from Guinea. COVID-19 may have jumped from bats to humans in the Chinese city of Wuhan.

Question 7

Doctors called her the most dangerous woman in America. An immigrant who had worked as a cook, she was New York’s patient zero, passing the fever to 51 people. By year’s end, 20,000 had died.

A. Mata Hari

B. Mary Mallon

C. Marie Curie

D. Bonnie Parker

Answer: B

In 1906, after a deadly summer of typhoid, medical investigators traced the source of the epidemic to Mary Mallon of Oyster Bay, Long Island. Newspapers called her “Typhoid Mary.” Her story ever since has been used by biology teachers to explain how a seemingly healthy asymptomatic person can unknowingly transmit a disease.

Question 8

Charles IV of Spain launched history’s first global immunization campaign. Pathogens from a diseased cow passed arm-to-arm in a human chain from the Canary Islands to the Americas and then on to the Philippines.

A. Spanish flu

B. Whooping cough

C. Rubella

D. Smallpox

Answer: D

Charles IV had lost his own infant daughter to smallpox. In 1803, after a vaccine had been developed from cow pus, the king appointed Francisco Javier de Balmis to lead a philanthropic expedition. Millions were inoculated worldwide.

WAR

Question 9

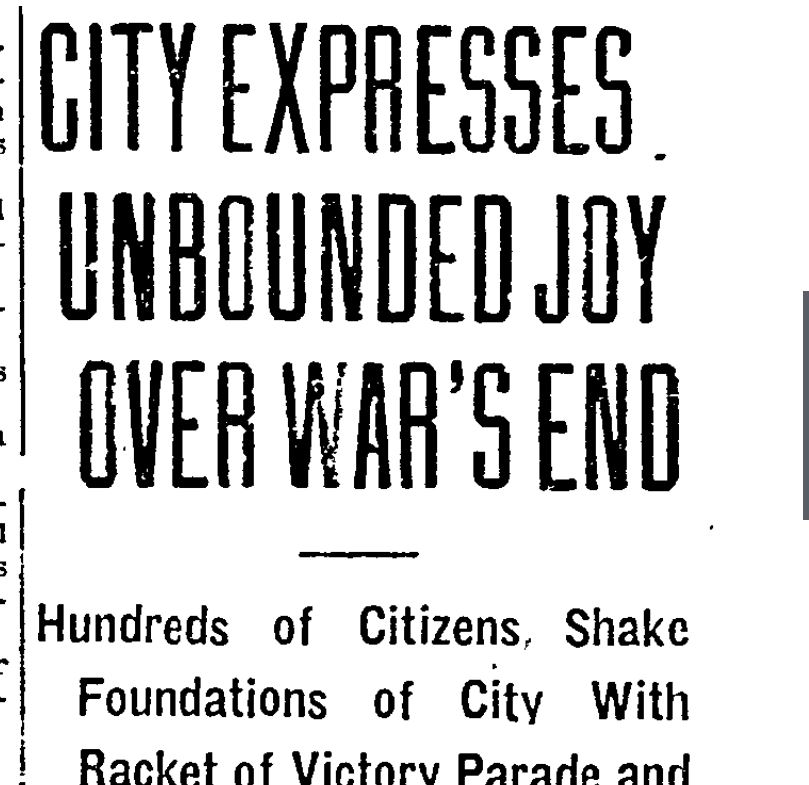

Jubilation on steps of the Idaho Statehouse overrode quarantines. Thousands discarded their protective face masks, fever-be-damned.

A. Covid-19

B. Spanish flu

C. Typhoid

D. H2N2 virus

Answer: B

The Spanish flu hit Idaho with returning trainloads of troops from the First World War. Boise’s Red Cross distributed facemasks. On November 11, nevertheless, Boiseans marched for Armistice Day. “Ten thousand yelling, shooting, screeching, tooting, rooting, laughing, talking citizens of Boise parade the streets,” the Statesman reported.

Question 10

Missionaries, it was alleged, had treated this virus with strychnine.

A. Dengue fever

B. Measles

C. Malaria

D. Smallpox

Answer: B

In 1847 a measles outbreak ravaged Washington’s Walla Walla Valley, where Marcus and Narcissa Whitman had founded a mission school. The fever spared whites but decimated Indian children. Cayuse warriors took revenge in a raid that killed 14 people. Fifty others, mostly women and children, were held as hostages for nearly a month.

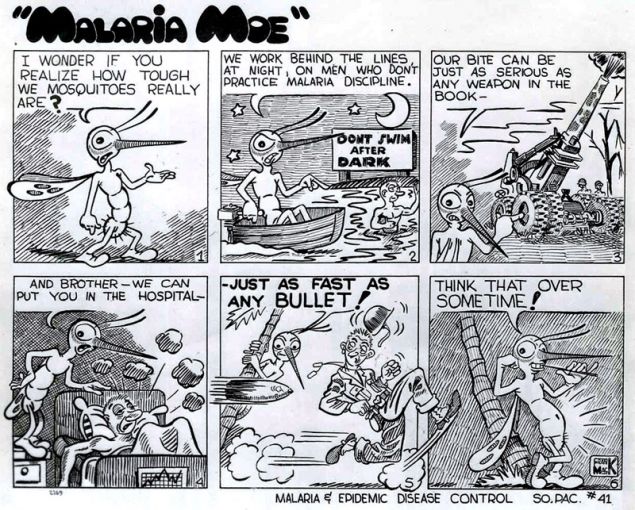

Question 11

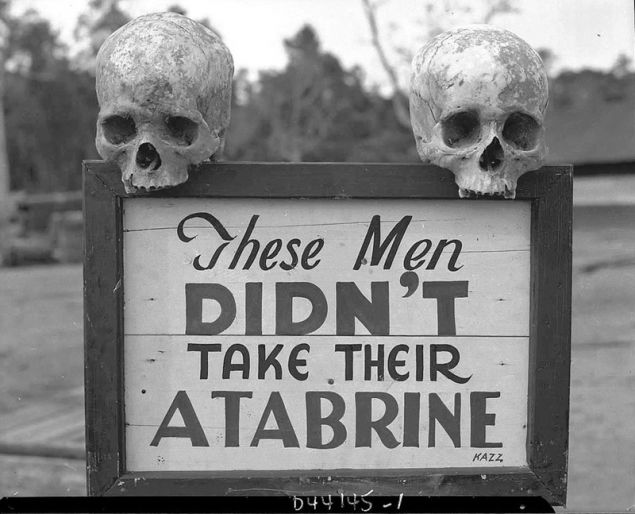

Great viral clouds of mosquitos beat back American forces. Commanders ordered that no soldier could be excused from combat without a temperature of at least 103°F.

A. Dengue

B. Malaria

C. Encephalitis

D. All of the above

Answer: D

WWII’s insecticide “bug bombs” cleared paths for American soldiers. But in 1942, before the army had weaponized DDT, mosquitos forced General MacArthur’s retreat from the Philippines’ Bataan Peninsula. Malaria in Sicily hospitalized more than 21,000 GIs.

Question 12

The plague forced Rome’s retreat in the war to recapture its former capital city. The emperor himself was stricken. Constantinople lost 5,000 people each day.

A. Plague of Antonius

B. Plague of Peloponnesian

C. Plague of Justinian

D. Plague of Cyprian

Answer: C

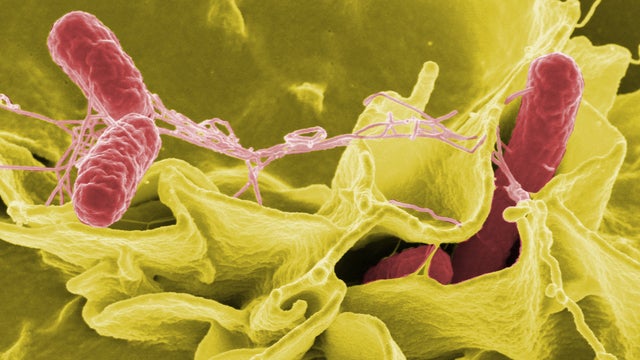

Epidemiologists blame the bacterial pathogen Yersinia pestis. Hitting the Roman army in 541, cutting the supply line of wheat from the Nile Valley, the Plague of Justinian may have killed more than a fourth of the emperor’s kingdom. Death estimates range from 25 to 50 million people.

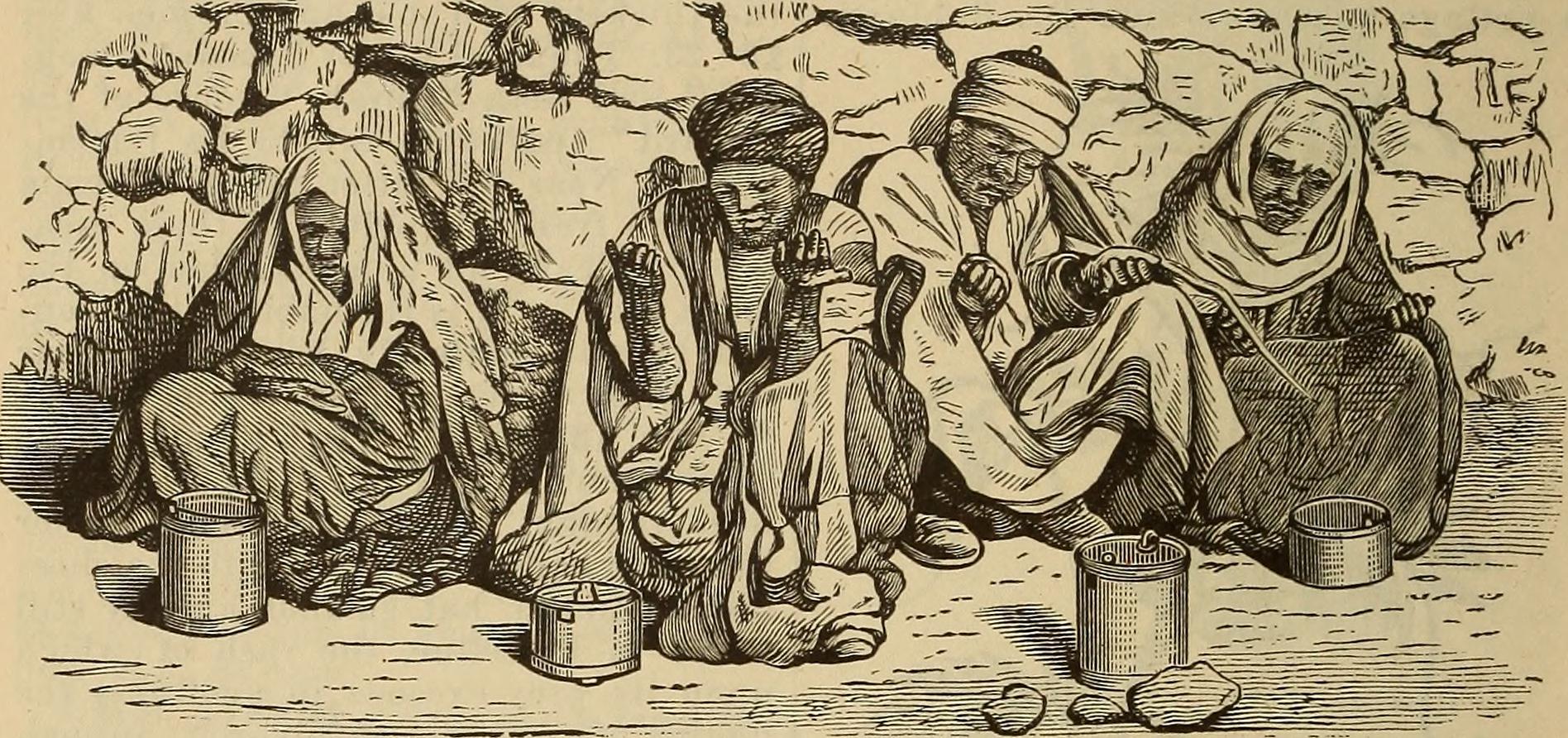

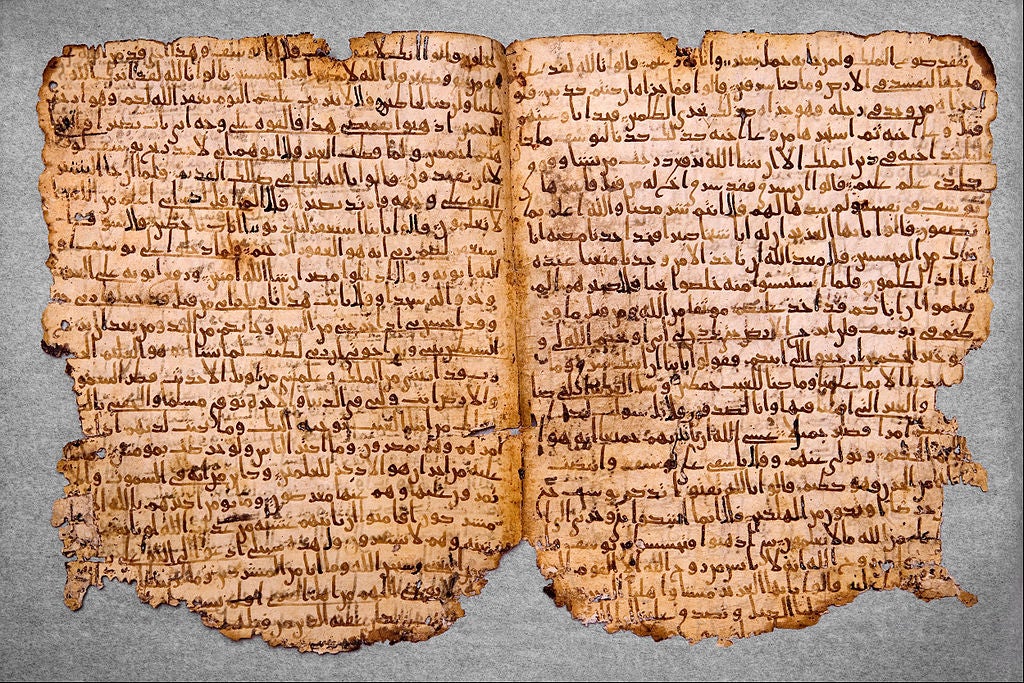

LITERATURE

Question 13

“One should keep away from a leper as one keeps away from a lion,” instructed the sacred text in its guide to pandemics. “If you hear of a plague in a land, do not enter it; and if it breaks out in the land where you stay, do not leave.”

A. Bhagavad Gita

B. New Testament

C. Holy Quran

D. Tibetan Book of the Dead

Answer: C

The Holy Quran outlined a system of social distancing and quarantine that anticipated modern epidemiological science. The Prophet Muhammad also taught the importance of proper hand-washing techniques.

Question 14

“Brothers abandoned brothers, uncles their nephews, sisters their brothers, and in many cases wives deserted their husbands,” wrote the Italian poet. “Fathers and mothers refused to nurse and assist their own children.”

A. Giovanni Boccaccio

B. Dante Alighieri

C. Lorenzo de’ Medici

D. Miguel de Cervantes

Answer: A

Ten young noblemen and women quarantine to escape plague-stricken Florence in Giovanni Boccaccio’s collection of 100 stories. The Decameron, published in 1353, buffooned human foibles with colorful tales of deceit, fickle fortune, and lust.

Question 15

“Through Asia, from the banks of the Nile to the shores of the Caspian, from the Hellespont even to the sea of Oman, a sudden panic was driven,” wrote novelist Mary Shelley, having lost family to this epidemic.

A. Puerperal fever

B. Dysentery

C. Malaria

D. All of the above

Answer: D

Mary Shelley’s The Last Man, published in 1826, forecasted human extinction via global pandemic. Shelley had lost her mother to puerperal fever. Dysentery had killed her infant daughter. Malaria had taken her son.

Question 16

Called “the romantic disease,” this affliction was hailed in Victorian times as poetic inspiration. Franz Kafka, John Keats, Harriet Beecher Stowe, Edgar Allen Poe, and Fyodor Dostoevsky all romanticized the disease. Victor Hugo had it cripple the spine of Notre Dame’s famous hunchback.

A. Tuberculosis

B. Spanish flu

C. Diphtheria

D. Mumps

Answer: A

Tuberculosis was thought to be a disease of the elite and artistic. It seemed to make women frail and pale in ways that inspired operatic glorification. A friend once told Victor Hugo that his one great fault was that, being free from tuberculosis, the novelist could never suffer enough to truly achieve.

VISUAL ARTS

Question 17

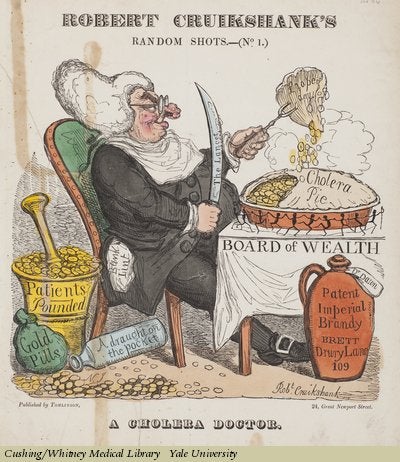

This epidemic corresponded with the rise of political editorial cartooning. Doctors sued cartoonists for slander, denouncing “atrocious falsehoods.”

A. 1831 London cholera

B. 1812 Ottoman plague

C. 1847 North American typhus

D. 1633 Massachusetts smallpox

Answer: A

The cholera epidemic of 1831-1832 killed an estimated 31,000 people in Britain alone. Cartoonists fueled the mistrust of doctors. Naysayers, citing cartoons, denounced cholera reports as a hoax.

Question 18

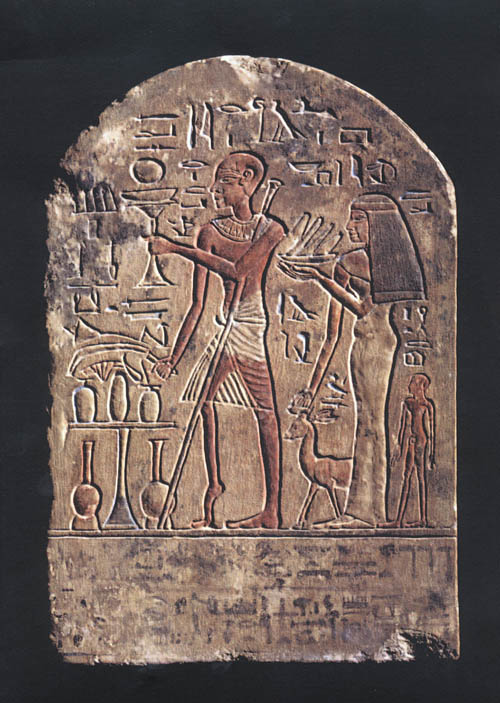

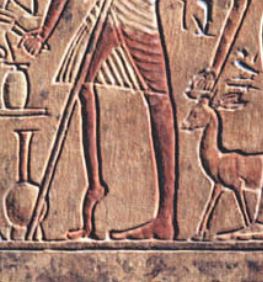

A carved stone from the time of the Pharaohs is thought to depict a victim of this neuromuscular virus.

A. Elephantiasis

B. Smallpox

C. Meningitis

D. Polio

Answer: D

Polio may have plagued the Nile Valley since antiquity. A funeral stele from 1400 BCE seems to picture a polio-stricken priest with a foot dangling from a shortened leg.

Question 19

The bubonic plague anticipates nuclear winter in this brooding stylized film about a knight’s encounter with death upon his return from a holy crusade.

A. The Seventh Seal

B. Resident Evil

C. Dawn of the Dead

D. Black Death

Answer: A

Swedish director Ingmar Bergman made no secret of the fact that his film The Seventh Seal was a metaphor for the coming apocalypse of nuclear war. Released in 1957, the film features the Grim Reaper and a medieval knight in a fateful game of chess for humanity’s soul.

Note: This article is part of The Blue Review’s Coronavirus Conversations, a special series on the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic.