By Nisha Bellinger, Boise State Political Science

Nisha Bellinger is an Assistant Professor of Political Science in the School of Public Service at Boise State University. Her research focuses on political economic themes. She is the author of Governing Human Well-Being: Domestic and International Determinants (Palgrave Macmillan 2018) and her research appears in journals such as European Political Science Review, International Political Science Review, and Journal of Politics, among others.

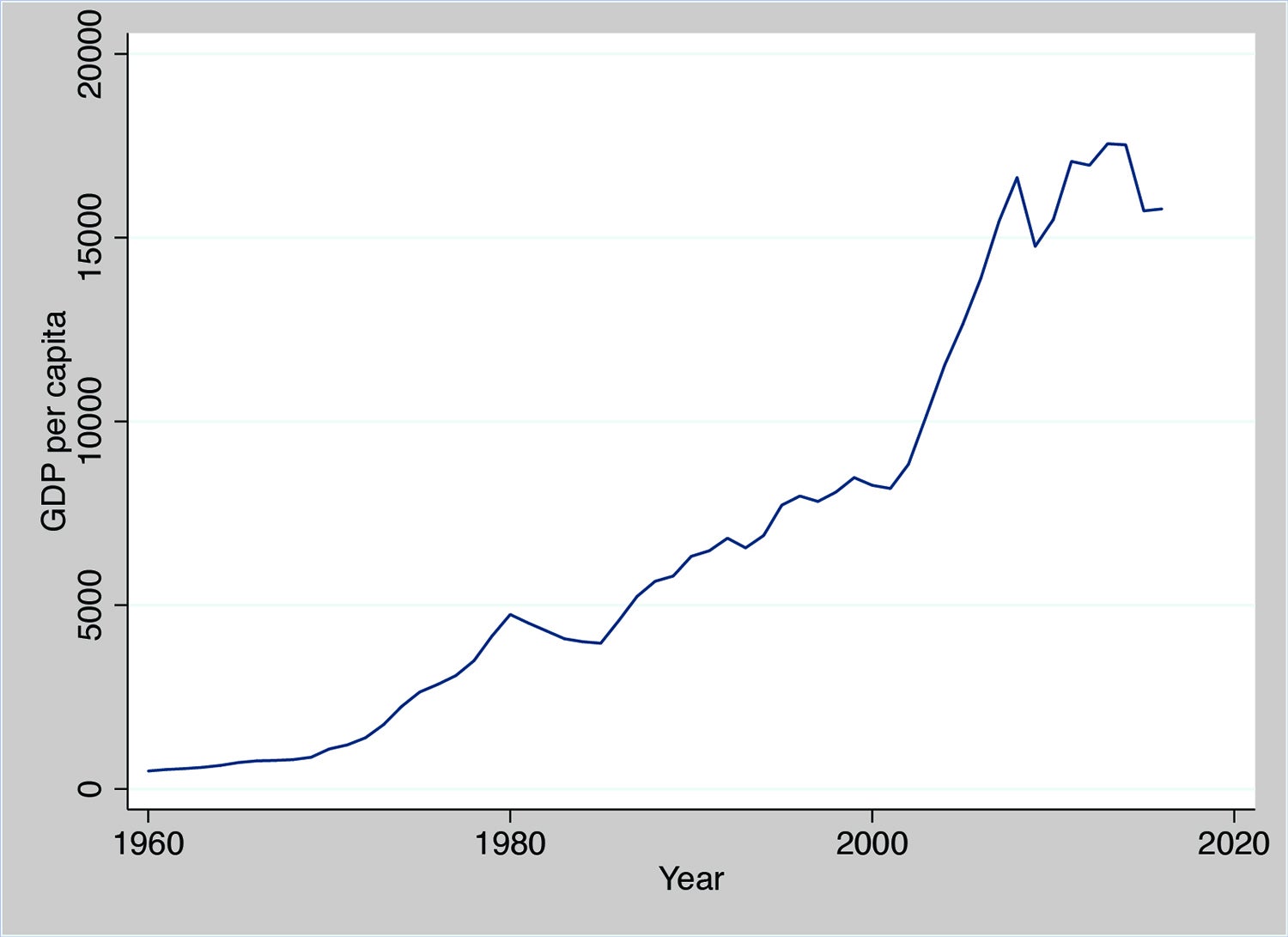

Chile has been consumed with large scale protests recently. An increase in metro fares sparked protests in the first place but they point to the bigger issue of income inequality within the country. Chile is classified as a high-income economy by the World Bank with a GDP per capita of approximately $15,000 (current US$) and a 4% GDP growth in 2018.

If the aggregate income level as captured by GDP per capita sufficiently captures development and enhances standard of living, then why are people protesting? Why are there grievances? The Chile example demonstrates one important point: focusing on GDP per capita solely does not give us a robust picture of development as it may not translate into a better quality of life for all individuals.

Development is more than income. Prominent developmental scholars such as Amartya Sen emphasize the significance of adopting a holistic approach to development that includes health, education, and political freedom, among other indicators. Similarly, the Human Development Index of the United Nations Development Programme, which provides an aggregate score of human development for each country globally, adopts a broad approach towards development to include income as well as education and health outcomes.

I am a political scientist and my research primarily focuses on the political determinants of human development outcomes. In this article, I highlight trends in three human development indicators globally over the past few decades, namely, GDP per capita, infant mortality, and secondary school enrollment. Furthermore, I discuss what these global trends tell us about development, more generally.

What do global human development trends look like?

Figure 1 displays the trend in GDP per capita from 1960 to 2016 from a global sample of countries. GDP per capita is one of the indicators that is commonly used to capture the level of income within countries. We see that over time income levels have increased.

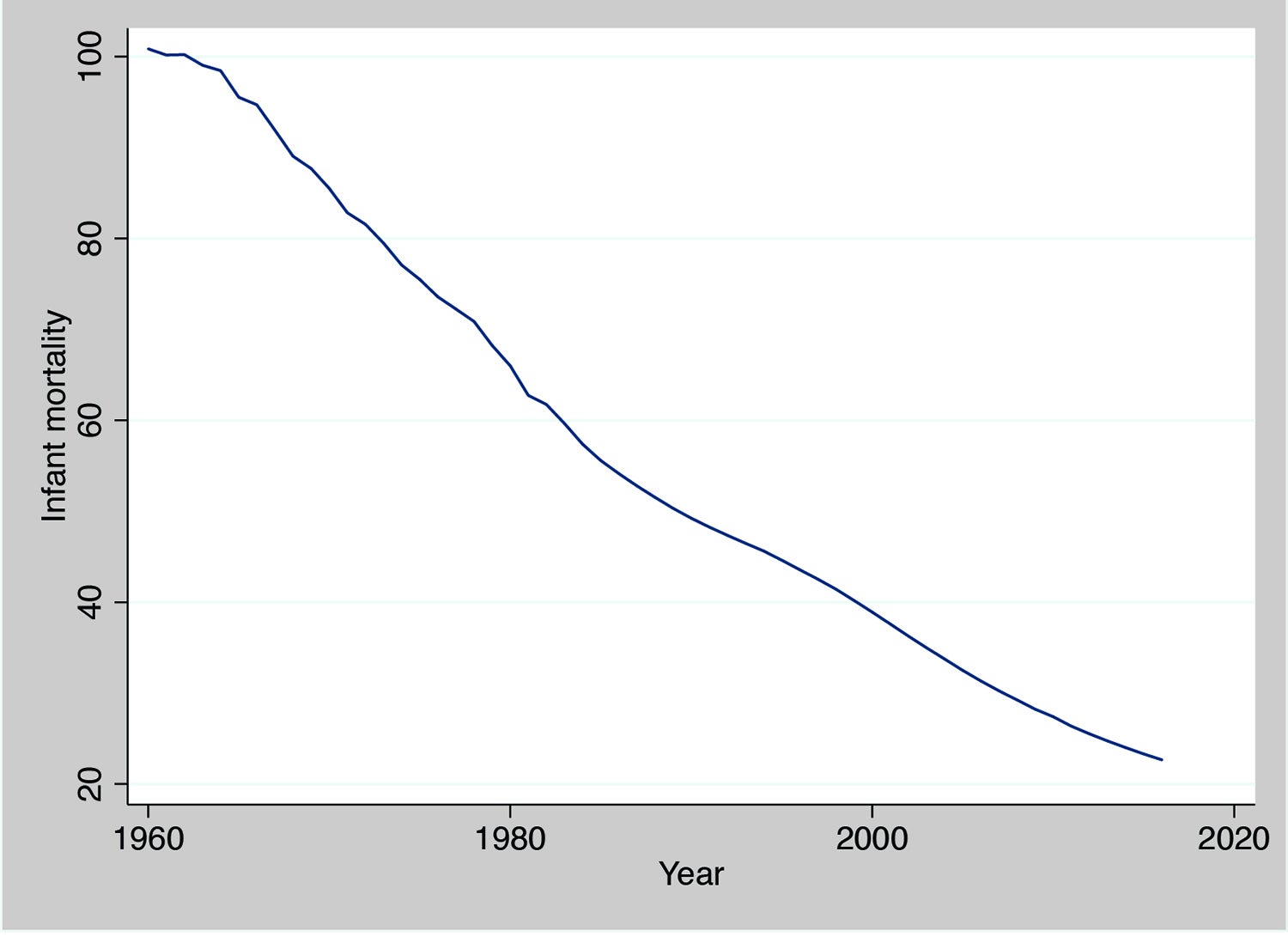

Figure 2 displays infant mortality rates from 1960 to 2016, which measures the number of infant deaths per thousand live births. Lower numbers of infant mortality indicate better health outcomes. Here again we see that over time infant mortality rates have been declining.

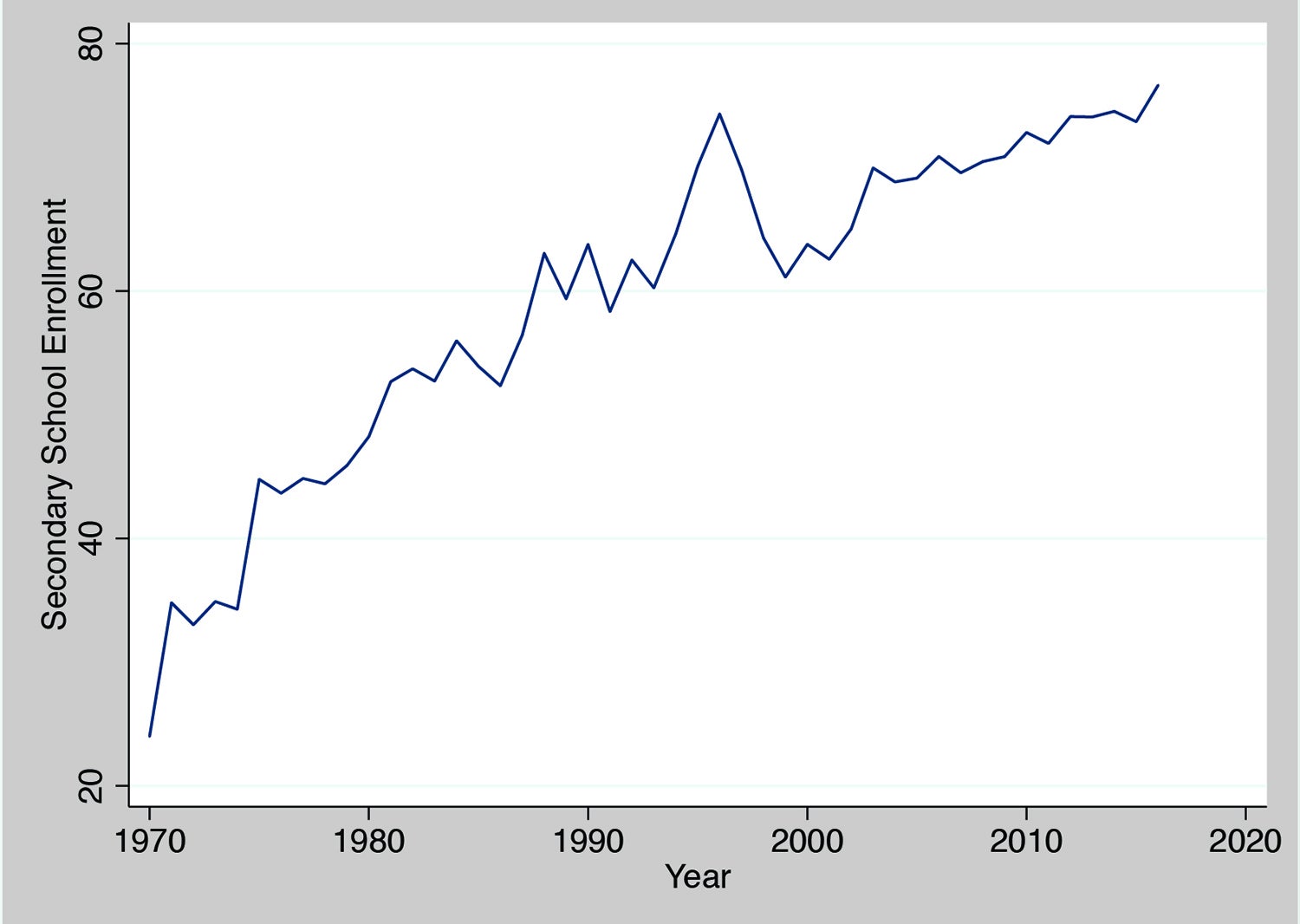

Figure 3 displays secondary school enrollment rates from 1970 to 2016 and is expressed as a percentage. Secondary school enrollment rates have been increasing globally over the years as well.

Overall, the three figures demonstrate that global trends over time in GDP per capita, infant mortality, and secondary school enrollment are promising. Income levels and secondary school enrollments have increased and infant mortality has declined over the years. The world is becoming richer and more educated with better health outcomes.

Two caveats are in order here. First, note that these figures are drawn from national-level data to capture global trends but they do not tell us about development patterns within a country.

Consider Kerala, a state in southern India. As per the most recent census, Kerala has an infant mortality rate of 10 while the national infant mortality rate in India is 33. The life expectancy rate, which refers to the number of years an individual is expected to live at the time of his or her birth, displays a similar pattern where life expectancy in the state of Kerala is approximately 74.9 years while the national rate is 67.9 years. This example demonstrates that there may be differences in development outcomes such as health within a single country. National-level data on income or health and education often mask differences within countries.

The second caveat relates to the relationship between income levels and health and education outcomes. Indeed, countries with higher levels of income generally have better health and education outcomes as compared to countries with lower levels of income. We see that from the three figures here: as income levels have increased over time, health and education outcomes have also improved. However, there are countries with lower income levels that have shown an improvement in health and education outcomes as well.

Let’s consider, Rwanda, in Africa. Rwanda is a low-income country with a GDP per capita of approximately US$770. It is also a country where well over 85% of the population is covered by health insurance. Indeed, these are challenges with the healthcare system in the country but what is noteworthy is that a low-income country has made considerable progress in meeting the healthcare needs of its population.

In fact, healthcare remains a concern even among high-income countries. For instance, healthcare is an important issue in upcoming elections in the United States as well as the U.K. Income levels certainly play an important role in improving health outcomes such as in these two countries that have low levels of infant mortality. However, the two examples demonstrate that high income levels (as captured by GDP per capita) may not automatically meet all the healthcare needs of the population.

Even though income levels have improved over time, income inequality has also increased over the years. According to the 2018 World Inequality Report, inequality has increased in nearly every region of the world with the top 1% of the global population getting twice the income growth since 1980 as compared to the 50% of the poorest global population. This suggests that an improvement in income levels such as an increasing GDP per capita may not bridge the income gap between individuals.

Increasing income inequality within countries has been a concern not just in Chile, as discussed above, but also in other parts of the world. Rising inequality is one of the reasons that led to the French Yellow Vest protests in France in Western Europe, Lebanon in the Middle East, and Ecuador in Latin America, among many other countries around the world.

Rising unrest due to inequality highlights the need for governments to address grievances of their citizens and adopt a broader approach towards development.

Are governments listening?

This is an important question and one that needs to be studied systematically. In the meantime, let’s look at recent policy initiatives proposed by governments in Europe who have come to power in recent years.

Political science research demonstrates that left-leaning governments are more likely to support policies that increase welfare spending and enhance the safety-net of their citizens. Yet we see right-leaning governments in Poland and Hungary propose policies that have generally been championed by left-leaning governments.

For instance, in Poland the governing Law and Justice (PiS) party won reelection in October 2019 and campaigned on raising funding for healthcare, raising the minimum wage, providing greater child benefits, and increased spending on infrastructure. Similarly, Hungary’s Prime Minister Viktor Orban of the right-wing Fidesz party has proposed tax and loan benefits for families and women raising children, in particular. Note that both these countries are classified as high-income by the World Bank but they have also seen rising inequality in recent years.

In this era of globalization and automation, governments around the world are likely to feel the pressure to do more to address the needs of their citizens. GDP per capita needs to be viewed as one of many indicators that can make substantive changes to people’s quality of life.