The Issue

As the margin of land that is occupied by both humans and wildlife grows, coexistence becomes more fraught and human-wildlife conflict ensues. Carnivore-inflicted depredation of livestock presents a serious issue in these human-wildlife shared areas.

Pressure from carnivore activity causes negative outcomes for ranchers and their stock, with yearly costs across the U.S. nearing $100 million, both from direct depredation and indirect loss of meat sale from increased stress levels in stock. This results in increased lethal action against infringing carnivores and continued loss of stock by ranching and herding communities. In addition, as wildlife affects ranchers so does grazing livestock impact the ongoing dynamics of wildlife.

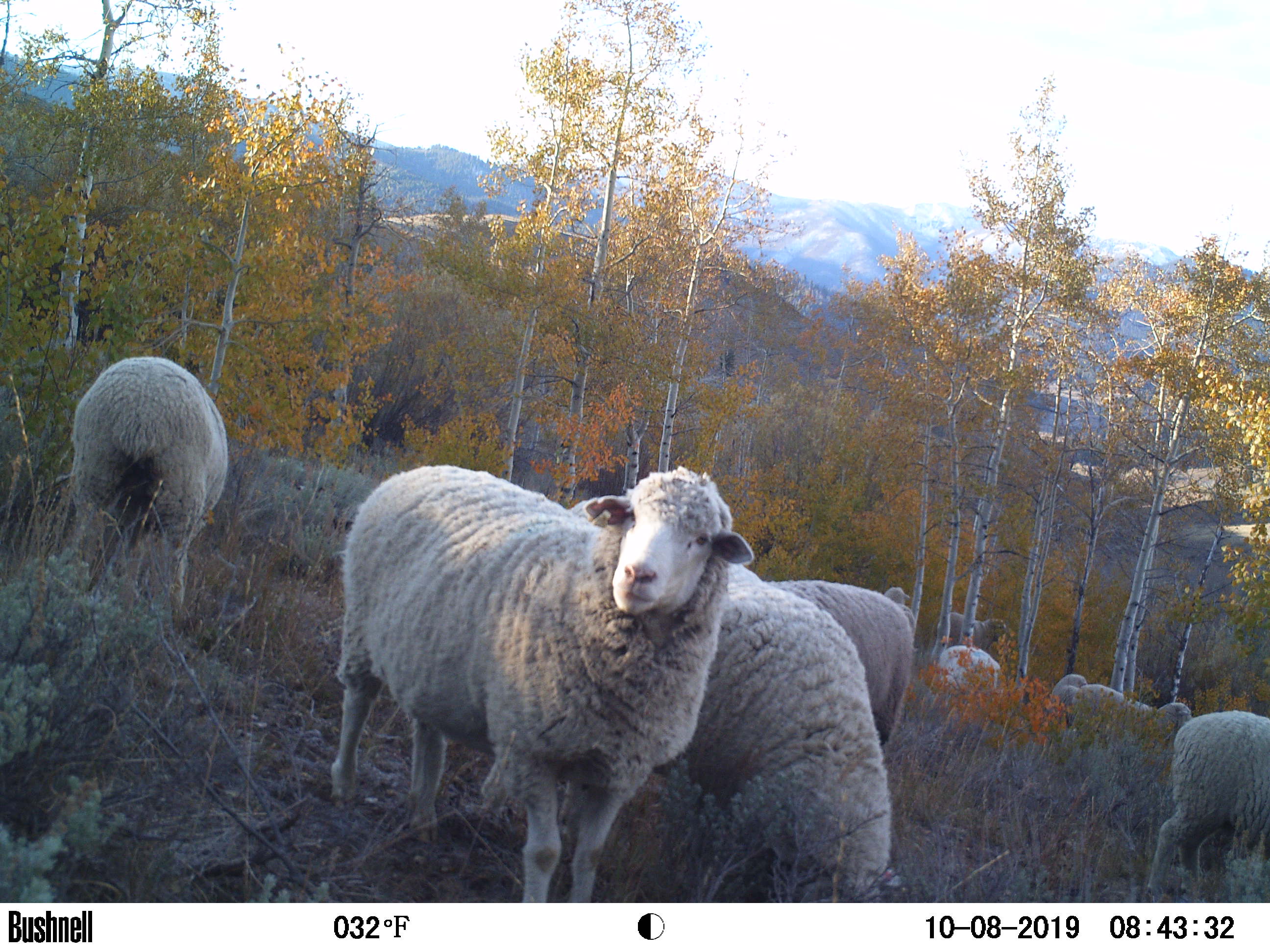

The montane regions of central Idaho are a good example of this system. A storied tradition of sheep-ranchers drive domestic sheep (Ovis aries) annually through US Forest Service grazing allotments under the continued pressure of depredation by local carnivore species such as American Black Bear (Ursus americanus), Coyote (Canis latrans), Mountain Lion (Puma concolor), and Gray Wolf (Canis lupus). These carnivores interact both with the environmental factors of their surroundings and the resident populations of their prey, namely Mule Deer (Odocoileus hemonius), Elk (Cervus canadensis), and Moose (Alces alces). Through this there is a pattern of use both spatially and temporally that can be observed in this predator-prey system.

A better understanding of these predator-prey dynamics and how they are affected by the influence of grazing sheep would benefit the decision making processes of ranchers and herders to avoid high-risk areas and improve grazing behaviors. This project aims to develop spatial and temporal analyses, including an occupancy model, based on data from a predator-prey-grazing system in the Big Wood River watershed in central Idaho.

The Data

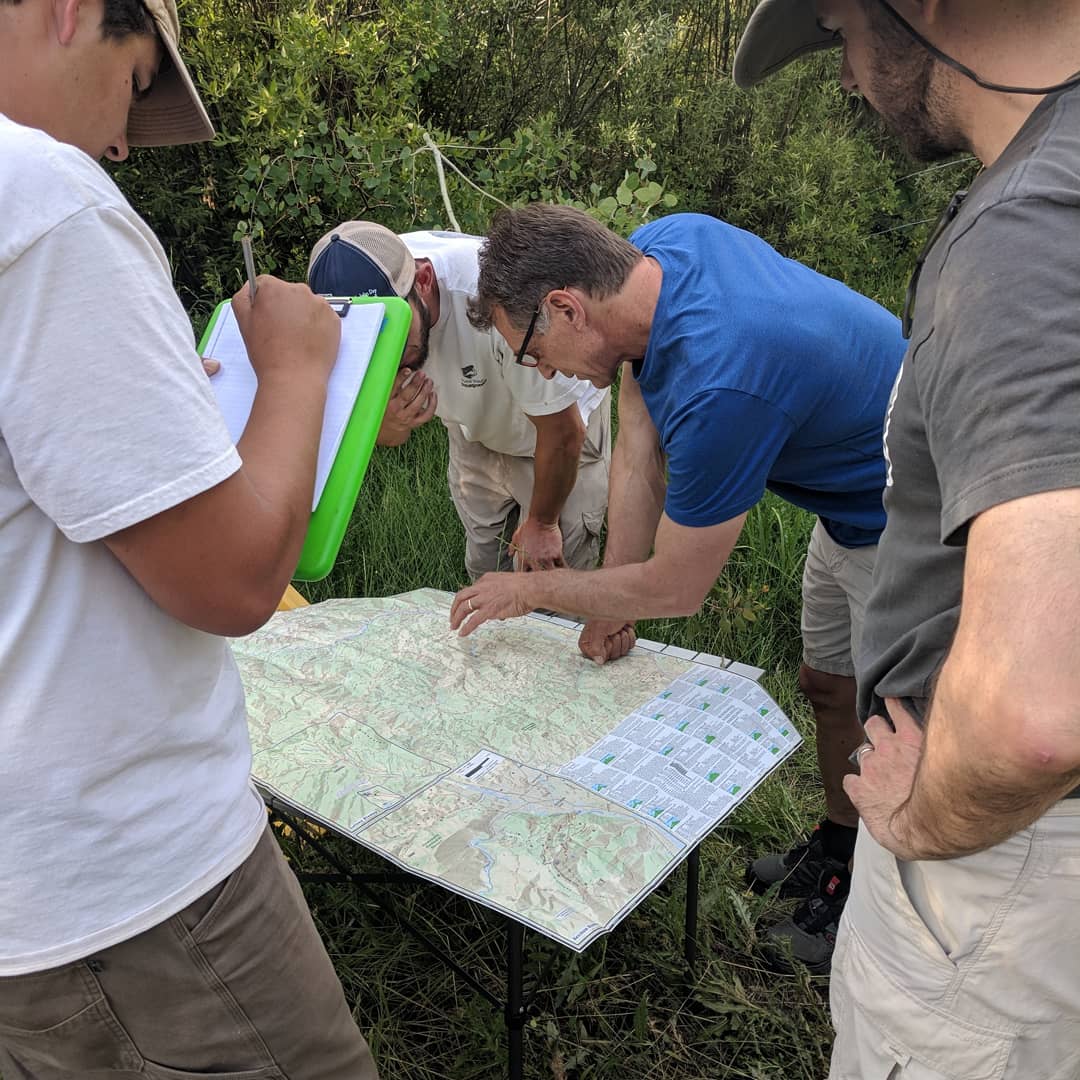

Spatial and temporal data for wildlife were procured from infrared-triggered trail cameras deployed around the Wood River Valley in May – October of 2018 and 2019. This is a classic method of extracting presence and abundance of large mammal wildlife species, as the long periods of continued observation give leave to capture photos of species that have large home ranges and high speeds of transit across them.

Cameras were deployed in order to provide coverage of the grazing allotments that make up the protected area by the Wood River Wolf Project, a non-profit organization created to reduce conflict between sheep and wolves by the use of non-lethal deterrents and strategic camera trap work. These grazing allotments are established by the US Forest Service and grazing agreements are filed each year with ranch operators to graze stock on public land for the summer season. Within these allotments, cameras were placed in opportune areas of wildlife use that co-occurred with areas likely to have grazing in the upcoming season.

Over both seasons, approximately 235,000 images were collected by cameras. These contained detections of wildlife, sheep, human recreation, and false triggers made by wind and vegetation. These images were downloaded and visually processed, leaving 8,200 independent detection events of wildlife, human recreation, and sheep.

In order to construct a mosaic of sheep grazing data reliable both spatially and temporally, four sources of data were collected: camera detections of sheep, known depredation sites and times, USFS annual operating instructions, and USFS weekly grazing updates.

The Next Steps and Collaboration

Following this data retrieval and analysis, efforts are now being made to develop statistical occupancy models that will predict predator presence across the study area given these data and incorporate the environmental and wildlife activity factors of the system. These models will provide decision support to ranching operations in the area, providing some predictive capability to how “risky” or “predator-prone” any given area is. Combined with efforts by the Wood River Wolf Project to provide herders with predator response tools (band kits), this will hope to lower conflict with predators and reduce costly depredations.

The most important use of this data is the sharing of its findings with the ranching operator and organization stakeholders in the study system. The two main deliverables to these stakeholders is a summary of predator detections for both seasons and a predictive risk map that will be developed with these data.

This project is also currently part of the Snapshot USA initiative currently being conducted by the eMammal program at the Smithsonian Institute. Over 60 field camera studies were collected from all 50 US States to contribute to the Snapshot USA Fall 2019 image data. These data will be used for cross-nation community ecology studies and promote citizen science.

The Team

Edward Trout, Boise State University

Dr. Neil Carter, University of Michigan

Dr. Kelly Hopping, Boise State University

Project Funding

USDA Conservation Innovation Grant

Wood River Women’s Foundation