If you’ve spent much time at our research stations, you probably know IBO’s research director, Jay Carlisle. And if you’re a long-time IBO friend, you might even remember when Jay was working on his PhD research project in the early 2000s. His research focused on songbird migration at Lucky Peak, and his work there was what created the long-term songbird migration project as we know it today.

But did you know that right after his PhD he also conducted research at another location: Camas National Wildlife Refuge in eastern Idaho? From fall of 2005 through spring of 2007 (2 seasons each of spring and fall), IBO scientists studied migrating songbirds at this site, which was known to birders as one of the best migration birding hotspots in the state.

In fact, during their time at Camas, the banding crew encountered some stunning rare bird records including the state’s first Wood Thrush and first 2 Connecticut Warblers (2 weeks apart!) along with numerous other noteworthy vagrants. More importantly, the project documented HUGE numbers of Wilson’s Warblers – especially in the fall migration – and impressive numbers of thrushes and many other Neotropical and shorter distance migrants.

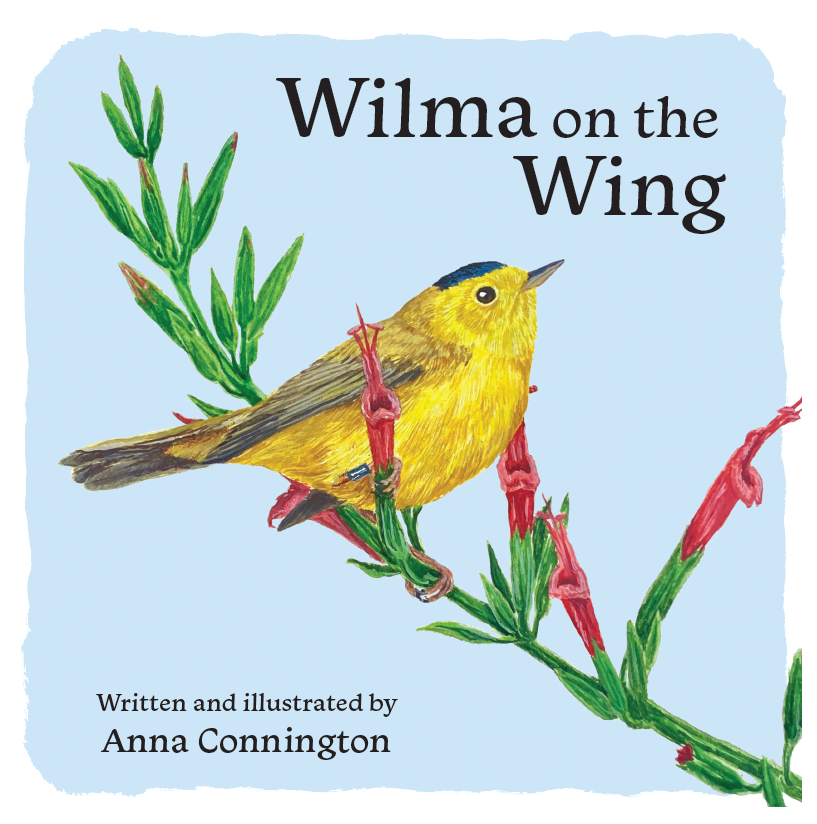

During autumn 2006, the Camas crew captured an immature female Wilson’s Warbler that was already banded – in Alaska! Wilson’s Warbler band # 2480-40861 was first captured and banded on Aug. 6, 2006 in Denali National Park and we recovered the bird at Camas NWR on Aug. 27 … three weeks and over 2,000 miles later!! This bird then stayed at Camas for two days and gained 0.5 grams – a gain of over 7% of body mass. Her story inspired IBO’s first children’s book, Wilma on the Wing, written and illustrated by Anna Connington.

When the initial 2-year project wrapped up in 2007, the ideal plan was to return to Camas within 5 years to follow up but budget cuts for US Fish and Wildlife Service and other factors have meant that 16 years have passed! Continued monitoring at key habitats like the refuge can help us understand the bigger picture of conservation in the region. As the years have passed, long-term drought (& resulting lower water availability) has altered the wooded habitats around the refuge headquarters – many of the large cottonwood trees have died and portions of the riparian vegetation also dried out.

Now, we finally have the chance to follow up on the project! Thanks to the Friends of Camas NWR, IBO has received funding to begin songbird banding at the refuge again. The project is coming together thanks to a partnership with an Idaho State University graduate student (and friend of IBO since he was a high school student!), Austin Young, and his advisor Dave Delehanty (Jay is serving on Austin’s thesis committee). Austin will use data from IBO’s original effort in 2005-2007, and conduct analyses comparing historic patterns of abundance, diversity, and body condition of migrants with what we see at the refuge during 2023 and 2024.

This spring marks the first season of our return to Camas. Beginning April 16th our hardy crew of banding technicians began work. And if you spent this spring in Idaho, you know it was no easy task! Despite snowstorms, high winds, and late leaf-out the crew persisted.

So far they’ve been rewarded with many captures of early season migrants including a nice push of Ruby-crowned Kinglets on day 2 along with a much earlier than expected Dusky Flycatcher on April 17.

Some other notable species include a Sharp-shinned Hawk, Townsend’s Solitaire, Vesper Sparrow, and Marsh Wren!

And as spring continues we expect numbers and diversity to increase when the Neotropical migratory species like warblers and tanagers begin to arrive. We’ll continue monitoring spring migration through June 15, then return again in the fall (~July 21 to October 15) to study birds as they head south for the non-breeding season.

We’re excited about the opportunity to revisit this important migratory stopover location, and look forward to comparing the results of Austin’s analysis with the data Jay & team collected more than 16 years ago.