Introduction

Training can be the most costly and time-intensive solution to performance problems, as noted in Thomas Gilbert’s Behavior Engineering Model. Cross-training workers to do multiple tasks as a way to ensure operational workflow is one approach to maximizing training’s benefits. What does research say about cross-training models that yield the greatest value in industrial work environments?

Article

Jordan, W. C., Inman, R. R., & Blumenfeld, D. E. (2004). Chained cross-training of workers for robust performance. IIE Transactions, 36(10), 953-967. https://doi.org/10.1080/07408170490487713

Background

Cross-training workers has been shown to increase workforce flexibility in meeting the challenges of workload variability. However, there are significant costs associated with training workers to do more than one task. One approach to getting the greatest value from cross-training is to form a chain of workers within an operational unit, where each worker is trained in a primary and secondary task only, and the assignments of those tasks are linked in a complete chain.

Researchers at General Motors examined several models to determine the most effective and efficient strategies for creating teams of multi-functional workers:

- NO CROSS-TRAINING, meaning that all workers are certified competent in a single task only;

- TOTAL CROSS-TRAINING, meaning that all workers are certified competent in all related tasks within their business unit;

- CHAINED CROSS-TRAINING, meaning that workers (all or some) are certified in a primary and a secondary task (aka, cross-training in a minimal complete chain).

In addition, researchers compared variations of chaining patterns in terms of cost and implementation difficulty.

Research and Findings

The researchers first evaluate their chaining models for a team of 13 maintenance workers who respond to equipment failures within an automotive plant in a single shift. Workers are certified in one or more areas (electrician, millwright, machine mechanic, and welder). Performance was evaluated for the three categorizations above by the repair’s mean time in the system, including wait time.

The researchers made a number of critical observations, the most significant of which is:

* Cross-training in a minimal complete chain provides most of the benefits of total cross-training for a fraction of the training cost.*

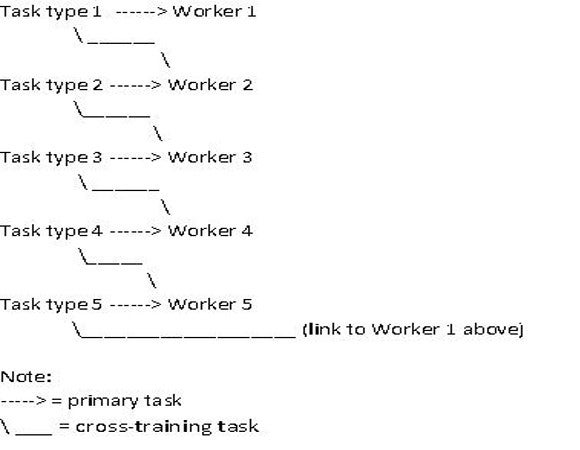

Below is an example illustrating a minimal complete chain with five workers and five task types. For example, Worker 2’s primary task is Task type 2, and s/he is cross-trained for Task Type 1.

The researchers, however, noted that if cross-training is inexpensive, it might be worthwhile to cross-train beyond this minimal complete chain. Conversely, minimally complete chains may not be optimal solutions for environments where there is little variability in operational workflow.

Questions for IPT-N Members

Do you use cross-training methods in your organization? Do you use a minimal complete chain method as illustrated above, or a total cross-training (i.e., all workers are trained for all tasks)? What did you learn from your cross-training methods?

Should cross-training be mandated or voluntary? What are the benefits of cross-training as a “bottom-up” versus a “top-down” initiative?

Workplace Oriented Research Central (WORC)

Prepared by OPWL Graduate Assistant, Susan Virgilio

Directed by OPWL Professor, Yonnie Chyung

Posted on October 16, 2012